- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

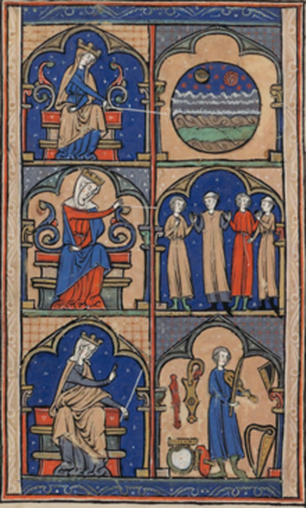

THE MASS

THE MASS: LITURGY AND WORK OF ART

By Judith A. Eckelmeyer

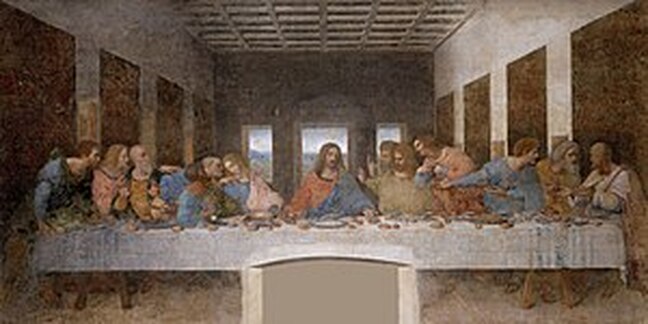

The roots of the Mass extend back to the earliest days of Christianity, when followers of Jesus within the Jewish community gathered to remember their leader after his death. St. Paul, in his first letter to the Corinthians (ca. 50-65), refers to the church’s practice of coming together for a common meal, during which bread and wine were blessed and consumed as a “remembrance” of the Lord. This event was considered a love-feast (Agape) or The Lord’s Supper. Later, the term Eucharist, or thanksgiving, was adopted for the celebration of the feast.

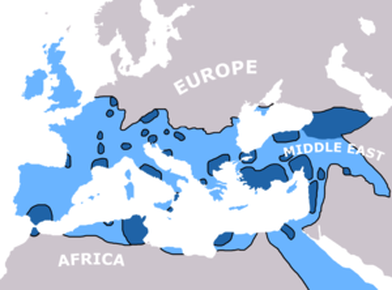

With the separation of the followers of Jesus from the Jewish community at the end of the first century, numerous communities of early Christians grew up in the lands around the Mediterranean, in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Over the next three centuries, the church, ever more scattered throughout the region, constructed more elaborate rituals of text and action to celebrate the sacrament of partaking the bread and wine, now separated from the meal itself. Accretions of texts and local languages from the various church communities as well as the original Jewish practice furnished the growing rituals. Musical settings of hymns, psalms, canticles, exclamations such as Alleluia, and liturgical poetry were employed from early Christian times, as were spoken or intoned texts of readings and structured prayers.

Antioch, Rome, and Jerusalem were the primary centers of early Christianity, but there were many sites where liturgy developed along local traditions and preferences. Some of these are Spain, with its Mozarabic Rite; France, with the Gallican Rite; the Alexandrian Rite of the Coptic Christians; Milan, with the Ambrosian Rite; and England’s Sarum Rite; and there were others in Western Christendom. Rome, though, was traditionally the site of the Apostle Peter’s martyrdom, and its bishop was accorded the unique role of carrying on the ecclesiastical lineage of St. Peter. Thus Rome, and the rite that developed there in the language of Latin, gradually became the official practice of the Christian church. Most of the liturgies that developed elsewhere were ultimately phased out.

The Western Church, through roughly the first 1000 years of the Common Era, developed the liturgy (ritual text and actions) into the format that was to be relatively consistent for the following five centuries. The Lord’s Supper, as the principal rite, accrued almost all of its texts by then. Other services, called Divine Offices, occurred at roughly three-hour intervals during the course of a day (starting about 3 am); these contained prayers, psalms, antiphons, canticles, hymns, lessons or scripture readings, versicles and responses.

The Western Church, through roughly the first 1000 years of the Common Era, developed the liturgy (ritual text and actions) into the format that was to be relatively consistent for the following five centuries. The Lord’s Supper, as the principal rite, accrued almost all of its texts by then. Other services, called Divine Offices, occurred at roughly three-hour intervals during the course of a day (starting about 3 am); these contained prayers, psalms, antiphons, canticles, hymns, lessons or scripture readings, versicles and responses.

Over the course of these developmental years, the concept of the Mass modified the earliest practice of a memorial feast, with the sanctification of bread and wine, to a re-enactment of the sacrificial death of Jesus to redeem believers from their sins. This change incorporated aspects of two ancient Jewish holy days--the Day of Atonement at the Temple in Jerusalem, where a sanctified lamb was slaughtered and its blood purified the sinner, or the priest consumed the flesh, and the scapegoat, bearing the sins of the community, was driven away to die in the wilderness; and the Passover ritual of slaughtering a lamb or goat, placing the blood on the doorposts and lintel of the home, then roasting and consuming the meat. As we shall see, the Mass text clearly reflects these elements.

In the following section we will examine the progression of events in a Mass, the kinds of texts, and, by looking at particular specific texts, identify the reason for the term “Mass” itself.

The Text of the Mass

Even in the early days of the church, only communicants—those who professed Jesus as Lord—could receive the bread and wine in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Non-communicants could participate in liturgy preliminary or preparatory to the actual consecration and partaking of the blessed elements of bread and wine. (Eventually, only the bread was offered to the communicant.) The preparatory segment of the Mass included Introductory Rites, consisting of opening prayers and chants; and the Liturgy of the Word, consisting of readings from the New Testament Epistles and Gospels, the homily or sermon, the statement of belief, and prayers. The Liturgy of the Eucharist, reserved for communicants, included offerings, the consecration of the Eucharistic elements of bread and wine, the communicants’ partaking of the elements, and the concluding prayer and dismissal.

As a constant element of Christian worship from the earliest days of the church, the Lord’s Supper, eventually called the Mass, was celebrated in all times of the year. This meant that, apart from the actual words remembering the institution of the sacrament and other necessary elements such as the statement of belief, there would necessarily have to be seasonal differences in the prayers, psalms, and other texts that led up to or accompanied the sacrament. The variable parts of the service are called the Proper, in that they are “proper” to a particular day, season, feast, or event. The texts and many of the chants of the Proper are among the oldest of the church. However, other parts of the service would never vary; these are called the Ordinary texts. (As a point of interest, almost all of the contents of the Divine Offices would fall under the “Ordinary” category, while the Mass contained nearly equal sections of Ordinary and Proper texts.)

Six moments in the Mass emerged as regularly recurring elements with texts that never varied. The incipits (first words) of these events are: Kyrie eleison, Gloria in excelsis, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and Ita missa est. We will examine each of these texts in detail below, but for now it is important to note the Ita missa est. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, this phrase means “Go, it is the dismissal” or “Go, you are dismissed”; this phrase was originally used to dismiss the catechumens (those not yet members of the church) before the Liturgy of the Eucharist, but now it ends the service and sends the congregants back into the world. The term Mass derives from “missa” and became the term for the service itself. Other concluding blessings often substituted for the “Ita missa est” and this original dismissal formula was eventually dropped from the list of “Ordinary” texts.

Progressing Through the Mass

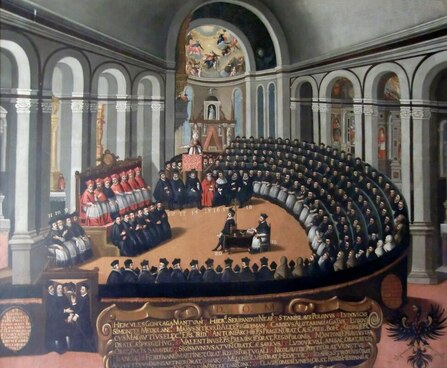

In this section we will journey through a typical Mass, observing the kinds of liturgical events and how the two kinds of text, Ordinary and Proper, occur throughout the Mass. This version of the Mass is taken from mid-20th century usage, conforming to the 1961 Liber usualis. However, the Mass was not always structured thus. Major changes occurred in the Middle Ages as texts were added or made to conform with authoritative dictates; modifications such as those at the Council of Trent in the 16th century and in the reforms of 1963 revised the Mass text and liturgical actions. Nevertheless, our model in this essay will serve as a framework on which to hang further discussion of the music of the Mass, to be considered later.

Introductory Rites:

Introit (literally, “he enters”, referring to the priest or celebrant; Proper).

Introit (literally, “he enters”, referring to the priest or celebrant; Proper).

The Introit consists of a short poetic text, called an antiphon, followed by a psalm verse, and concluding with the repetition of the antiphon. There are numerous antiphons, so the particular day or event would dictate the choice of the appropriate one for the Mass. One antiphon needs special mention: “Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine” (Give him eternal rest, Lord). This opening of the Introit of the Mass for the Faithful Departed is the source of the term “Requiem Mass”.

Duruflé Requiem, Op. 9 I. Introit and Kyrie

Maurice Duruflé, conductor

Hélene Bouvier, mezzo-soprano | Xavier Depraz, bass | Marie-Madeleine Duruflé-Chevalier, organ | Philippe Caillard and Stéphanie Caillat Chorales | Orchestra des Concerts Lamoureux

Maurice Duruflé, conductor

Hélene Bouvier, mezzo-soprano | Xavier Depraz, bass | Marie-Madeleine Duruflé-Chevalier, organ | Philippe Caillard and Stéphanie Caillat Chorales | Orchestra des Concerts Lamoureux

At different times in the evolution of the practice of the liturgy entire psalms would be sung, using special formulas called psalm tones. Usually, the psalm would be concluded with the “Gloria Patri” (the lesser doxology, or “glory-giving”), consisting of the words: “Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto. Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper, et in saecula saeculorum. Amen” (Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is now and always and to the ages of ages. Amen). Essentially, this textual formula conferred a Christian usage to a Jewish text from the Old Testament.

Gloria Patri (Gregorian Chant)

Rebecca Gorzynska

Rebecca Gorzynska

Kyrie (Ordinary).

This one word is the short title for a two-phrase text, “Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison”, Greek phrases meaning “Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy”. The phrases originated in both Pagan antiquity and the Old Testament. In liturgical use, each phrase is said three times, and then the first phrase is given again three times. Thus:

|

Kyrie eleison, Kyrie eleison, Kyrie eleison;

Christe eleison, Christe eleison, Christe eleison; Kyrie eleison, Kyrie eleison, Kyrie eleison. |

The three-times-three structure of the Kyrie vividly identifies it as Trinitarian, reflecting God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and thereby marks it as a Christian text regardless of its origins.

Kyrie I from Mass I

Gregorian Chant (Brébeuf Hymnal)

Matthew J. Curtis, Vocalist

Gregorian Chant (Brébeuf Hymnal)

Matthew J. Curtis, Vocalist

Gloria (Ordinary).

Again, this single word is the short-hand way of referring to a much longer text, “Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis”, “Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to men of good will”. Also an ancient text of the church, this first phrase can be found in the gospel of Luke when the angels announce Jesus’s birth to the shepherds. There is much more to follow in this long element, which is an extended glorification of God that also incorporates many instances of belief statements about the person of Jesus. This text is called the “greater doxology” to distinguish it from the “lesser doxology”.

|

Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to men of good will. Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te. We praise Thee, we bless Thee, we adore Thee, we glorify Thee. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam. We give Thee thanks for Thy great glory. Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens. Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father omnipotent. Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe. Lord, the only begotten son, Jesus Christ. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris, Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Who bears the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostrum. Who bears the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis. Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us. Quoniam tu solus sanctus. Tu solus Dominus. Tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe. For You alone are holy, You alone are the Lord, You alone are the highest, Jesus Christ. Cum Sancto Spiritu, in Gloria Dei Patris. Amen. With the Holy Spirit, in the Glory of God the Father. Amen. |

The Gloria, a joyful text, is omitted in penitential seasons (Lent and Advent) and in the Requiem Mass.

Gloria

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Collect (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

This is a short opening prayer, concluding the Introductory Rites.

This is a short opening prayer, concluding the Introductory Rites.

Collect · Bonaventure Choir

Liturgy of the Word:

Epistle (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

The Epistles are letters, most of them from St. Paul, to individuals or to church communities in the mid- to late first century. In the earliest years of the church, they would have encouraged, corrected, and sustained the far-flung Christian movement, being read in the assembly as a part of the gathering for the Lord’s Supper. On occasion, an Old Testament text might be read in place of a New Testament Epistle, but was nevertheless called “the Epistle”.

The Epistles are letters, most of them from St. Paul, to individuals or to church communities in the mid- to late first century. In the earliest years of the church, they would have encouraged, corrected, and sustained the far-flung Christian movement, being read in the assembly as a part of the gathering for the Lord’s Supper. On occasion, an Old Testament text might be read in place of a New Testament Epistle, but was nevertheless called “the Epistle”.

Gradual (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

The response to the Epistle was a psalm (or, occasionally, a reading from other books of the Bible). Originally an entire psalm was chanted by a cantor, to which the congregation would respond with a short verse or part of a verse from the psalm. The Gradual became the focus of musical endeavor, for the verse response to the psalm grew into a long, ornate plainchant composition. We will discuss this further in a later section of this essay.

The response to the Epistle was a psalm (or, occasionally, a reading from other books of the Bible). Originally an entire psalm was chanted by a cantor, to which the congregation would respond with a short verse or part of a verse from the psalm. The Gradual became the focus of musical endeavor, for the verse response to the psalm grew into a long, ornate plainchant composition. We will discuss this further in a later section of this essay.

Tu es Deus (6th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Gradual)

Performed live by the monks of St. Benedict's Monastery in São Paulo (Brazil)

Performed live by the monks of St. Benedict's Monastery in São Paulo (Brazil)

Alleluia, Tract, and Sequence (Proper).

The ancient word of praise precedes and follows a verse, similar to the antiphon-psalm-antiphon pattern. In penitential or sorrowful times, the Alleluia is replaced by a more solemn text called a Tract. According to the New Grove Dictionary, the term “Tract” is thought to have originated from the Latin “to draw”—texts that were drawn up from the heart in grief.

Both Alleluia and Tract melodies end in a long melisma—a series of notes on only one syllable, for example the “-a” of Alleluia. This long melisma was called the “Jubilus”. By the ninth century, words were being created to underlie the Jubilus to facilitate memorizing the melody. Eventually these melodies with their added text became independent chants, called Sequences. A late 9th- early 10th century Frankish composer, Notker of St. Gall, not only wrote many Sequences but discussed them in the preface to his collection of Sequence texts. In the way of creative folk at every time, more and more Sequences were devised to the point of superabundance, until a moratorium was called; of all of these only four Sequences were retained (a fifth to be added in the 18th century). The most well-known Sequence today is “Dies irae”, the long poem about the Day of Judgement, used in the Requiem Mass.

The ancient word of praise precedes and follows a verse, similar to the antiphon-psalm-antiphon pattern. In penitential or sorrowful times, the Alleluia is replaced by a more solemn text called a Tract. According to the New Grove Dictionary, the term “Tract” is thought to have originated from the Latin “to draw”—texts that were drawn up from the heart in grief.

Both Alleluia and Tract melodies end in a long melisma—a series of notes on only one syllable, for example the “-a” of Alleluia. This long melisma was called the “Jubilus”. By the ninth century, words were being created to underlie the Jubilus to facilitate memorizing the melody. Eventually these melodies with their added text became independent chants, called Sequences. A late 9th- early 10th century Frankish composer, Notker of St. Gall, not only wrote many Sequences but discussed them in the preface to his collection of Sequence texts. In the way of creative folk at every time, more and more Sequences were devised to the point of superabundance, until a moratorium was called; of all of these only four Sequences were retained (a fifth to be added in the 18th century). The most well-known Sequence today is “Dies irae”, the long poem about the Day of Judgement, used in the Requiem Mass.

Gospel (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

The reading is from one of the first four books of the New Testament—Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John—in which Jesus’s life and work are narrated.

The reading is from one of the first four books of the New Testament—Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John—in which Jesus’s life and work are narrated.

Homily (Proper). (Spoken.)

The sermon.

The sermon.

Credo (Ordinary).

This is the first word of a long statement of belief, one of a number that were devised over the early centuries of the church. This particular text was created in a kind of “committee” agreement during the great Council of Nicea in 325 CE, and so was called the Nicene Creed. Although created early in the history of the church, the Nicene Creed was the last addition to the Ordinary, appearing first at the end of the eighth century.

This is the first word of a long statement of belief, one of a number that were devised over the early centuries of the church. This particular text was created in a kind of “committee” agreement during the great Council of Nicea in 325 CE, and so was called the Nicene Creed. Although created early in the history of the church, the Nicene Creed was the last addition to the Ordinary, appearing first at the end of the eighth century.

|

Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem,

I believe in one God, Father almighty, factorem caeli et terra, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. maker of heaven and earth, all things visible and invisible. Et in unum Dominum, Jesum Christum, Filium Dei unigenitum. And in one Lord, Jesus Christ, only begotten Son of God. Et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula. And born of the Father before all ages. Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine, Deum verum de Deo vero. God from God, light from light, true God from true God. Genitum, non factum, consubstantialem Patri: per quem Omnia facta sunt. Born, not made, of one substance with the Father: through whom all things were made. Qui propter nos homines, et propter nostrum salute descendit de caelis. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven. Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto ex Maria Virgine, et homo factus est. And was incarnate by the Holy Spirit, of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato: passus, et sepultus est. He was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate: suffered, and was buried. Et resurrexit tertia die, secundum Scripturas. And he arose on the third day, according to the Scriptures. Et ascendit in caelum: sedet ad dexteram Patris. And he ascended into heaven: he sits at the right hand of the Father. Et iterum venturus est cum Gloria judicare vivos et mortuos: cujus regni non erit finis. And he will come again with glory to judge the living and the dead; of his reign there will be no end. Et in Spiritum Sanctum Dominum, et vivificantem: qui ex Patre, Filioque procedit. And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. Qui cum Patre, et Filio simul adoratur, et conglorificatur: qui locutus est per Prophetas. Who together with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified: who has spoken through the Prophets. Et unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam. And in one holy catholic and apostolic Church. Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum. I confess one baptism for the remission of sins. Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Et vitam venture saeculi. Amen. And I await the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen. |

English Chant Mass - Credo (Creed)

Richard Rice, vocalist

Richard Rice, vocalist

Liturgy of the Eucharist:

Offertory (Proper).

A time to receive gifts, including the elements of bread and wine that were to be consecrated for the Eucharist, the Offertory texts and chants are “time fillers”. They were originally psalms, but non-psalm texts developed even in early times.

A time to receive gifts, including the elements of bread and wine that were to be consecrated for the Eucharist, the Offertory texts and chants are “time fillers”. They were originally psalms, but non-psalm texts developed even in early times.

OFFERTORY • Passion (Palm) Sunday • SIMPLE ENGLISH PROPERS

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Preface (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

A few short sentences by the officiant and responses from the communicants set the tone of thanksgiving for the coming sacrament; the celebrant then declaims the obligation of all in heaven and earth to glorify God. The text leads directly to the angels’ song of praise:

A few short sentences by the officiant and responses from the communicants set the tone of thanksgiving for the coming sacrament; the celebrant then declaims the obligation of all in heaven and earth to glorify God. The text leads directly to the angels’ song of praise:

Preface Dialogue (New Translation)

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Sanctus (Ordinary).

This short but powerful text originated in both the Old Testament and the New; it became a part of the Mass by about 400 CE. By the eighth century, both clergy and congregation were to sing the texts.

This short but powerful text originated in both the Old Testament and the New; it became a part of the Mass by about 400 CE. By the eighth century, both clergy and congregation were to sing the texts.

|

Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus sabaoth.

Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts. Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Heaven and earth are full of Thy glory. Hosanna in excelsis. Hosanna in the highest. Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in excelsis. Hosanna in the highest. |

Sanctus (Latin)

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Canon (Ordinary, with some Proper passages). (Spoken/intoned.)

This section contains St. Paul’s words of the institution of the Last Supper and the prayer of consecration.

This section contains St. Paul’s words of the institution of the Last Supper and the prayer of consecration.

The Canon of the Mass @ St. John's Detroit

Pater Noster (Ordinary). (Spoken/intoned.)

The Lord’s Prayer:

The Lord’s Prayer:

|

Pater noster, qui es in caelis: sanctificetur nomen tuum;

Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be your name; Adveniat regnum tuum; fiat voluntatis tua, sicut in caelo, et in terra. Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as in heaven. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie; Give us today our daily bread; et dimitte nobis debita nostra, sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. And forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem. Sed libera nos a malo. Amen. And do not lead us into temptation. But deliver us from evil. Amen. |

Our Father (Pater Noster)

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Agnus Dei (Ordinary).

Here is the point at which St. John’s description of Jesus as the Lamb of God intersects with the sacrificial lamb of the Day of Atonement and the Passover, as discussed earlier. The three-fold statement replicates the three-fold Kyrie eleison. The variant of the Agnus Dei for the Requiem Mass will be shown at the end of the usual text.

Here is the point at which St. John’s description of Jesus as the Lamb of God intersects with the sacrificial lamb of the Day of Atonement and the Passover, as discussed earlier. The three-fold statement replicates the three-fold Kyrie eleison. The variant of the Agnus Dei for the Requiem Mass will be shown at the end of the usual text.

|

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem. Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, give us peace. For a Requiem Mass: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem. Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, give him rest. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem sempiternam. Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, give him rest eternal. |

Agnus Dei

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Communion (Proper).

Like the Offertory, this portion of the Mass fills time as communicants receive the bread (and wine, in some cases); texts are from psalms or other sources.

Like the Offertory, this portion of the Mass fills time as communicants receive the bread (and wine, in some cases); texts are from psalms or other sources.

Invitation to Holy Communion

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Post-Communion Prayer (Proper). (Spoken/intoned.)

Prayers of thanksgiving and continuation in the faith.

Prayers of thanksgiving and continuation in the faith.

Post Communion Prayer

St. Alban's Catholic Church

St. Alban's Catholic Church

Ita, missa est (Ordinary). (Now spoken/intoned.)

The dismissal, or an alternative such as “Benedicamus Domino—Let us bless the Lord”, is followed by the response “Thanks be to God”.

The dismissal, or an alternative such as “Benedicamus Domino—Let us bless the Lord”, is followed by the response “Thanks be to God”.

Dismissal

Church Music Association of America

Church Music Association of America

Music of the Mass in the Western Church

The roots of the Christian church stem from Jewish practice of the first century, and the earliest liturgical chants emerged from Jewish chants of the time, as well as from pagan sources. Numerous versions of the sung liturgy existed in sites all over the Christian world, however. By about the beginning of the eighth century Frankish kings and Roman leaders of the Church began to standardize the liturgy, developing a body of chants that were eventually attributed to Gregory the Great, who, surprisingly, reigned as Pope from 590-604, some 200 years earlier. The dominance of the Franks, and especially the strength and extent of the Holy Roman Empire, assured the adoption of the Gregorian liturgy in the Western church from the eighth century, at the same time that the Byzantine Rite continued on another trajectory in the Eastern Church. Gregorian chant, then, is the foundation of the development of musical treatment of Mass text in Western music.

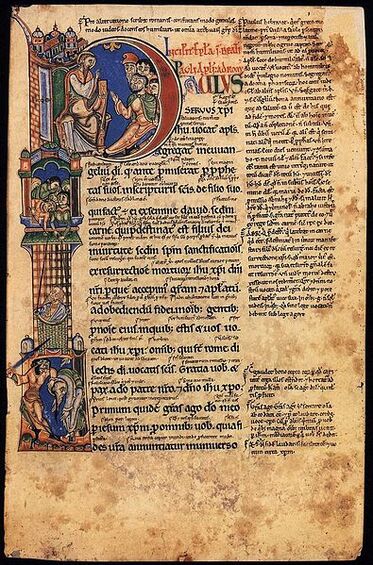

Until proof of polyphony appeared in written documents, monophony (a single, unharmonized melody line) is thought to have prevailed in the singing of Gregorian chant. However, it is clear that an unwritten tradition of harmonizing chant melodies had developed sufficiently that by the ninth century two treatises, Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, explained and demonstrated a way to sing a second melody, not a drone, against the chant. These treatises give the earliest proof of polyphony in Western music. What they describe is a genre called organum (accent on the first syllable; pl. organa), which is unequivocally sacred and built upon chant. In all organum, all voice parts sing the same liturgical text at the same time; what differs is the melody to which the text is sung in each voice part.

Organum went through several stages of development from the ninth through the thirteenth centuries. Here, in short form, are the main points of what happened:

Parallel organum: the earliest stage, in which the chant melody remained above the added voice, and the intervals between them were constantly “perfect”—fourths, fifths, unisons, or octaves (derived from ancient Pythagorean acoustics). A modified form of parallel organum allowed the voices to diverge from a unison to attain the perfect interval and then converge to a unison.

Musica enchiriadis - Secuencia "Rex caeli, Domine maris" (organum paralelo)

Konrad Ruhland; Capella | Antiqua München; Choralschola

Konrad Ruhland; Capella | Antiqua München; Choralschola

Free organum: the voices were permitted to cross, nevertheless retaining the relationship of a perfect interval.

Aquitanian organum: named for the region of Aquitaine in Southern France, where manuscripts from the early twelfth century from the Abbey of St. Martial in Limoges show this style; the chant melody, called the tenor because it “holds” the chant melody, is now below the added voice. The notes of the chant melody are prolonged while the added voice sings groupings of florid melismas (many notes per syllable). At times, though, the two voice parts would sing at about the same rate, in a style called discant. There is, then, a marked difference between the highly ornate or florid sections and the relatively simple sections in Aquitanian organum.

Notre Dame organum: named for the Cathedral of Paris, Notre Dame, which was constructed during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Features of Aquitanian organum appeared in Notre Dame organa: prolonged notes of the chant melody with passages of melisma in the added voices, as well as discant sections where all voices moved in roughly the same rhythm. But two significant developments mark Notre Dame organum. First, during the eleventh and early twelfth centuries there, the number of added voices, all of them above the tenor, increased dramatically; there were from one to three new melodies, creating as much as a four-part density. Second, with the increased number of voices, a mechanism for timing the occurrence of the pitches had to be devised to insure that the appropriate interval relationships were preserved. This latter feature impelled the invention of a notation system that conveyed duration of sound.

The durational values in Notre Dame organa were derived from ancient poetic meters in patterns called rhythmic modes. Groupings were made to total three units of time (honoring the Trinity for the sacred rite in which the music was used). So, the rhythmic patterns of Notre Dame organa were based on durational proportions of 2 + 1, or 1 + 2, and extensions of these patterns.

Another aspect of Notre Dame organum was the manifestation of composers’ names. Two of these are Leoninus, or Léonin (fl. ca. 1163-1190), and Perotinus, or Pérotin (fl. ca. 1200). Léonin is credited with the Magnus liber organi de graduali et antifonario, or Great Book of Organum for the gradual and antiphoner, consisting of two-voice polyphony. Pérotin revised the Magnus liber and composed three- and four-voice organa. These four-voice polyphonic works were the most advanced at the time.

The durational values in Notre Dame organa were derived from ancient poetic meters in patterns called rhythmic modes. Groupings were made to total three units of time (honoring the Trinity for the sacred rite in which the music was used). So, the rhythmic patterns of Notre Dame organa were based on durational proportions of 2 + 1, or 1 + 2, and extensions of these patterns.

Another aspect of Notre Dame organum was the manifestation of composers’ names. Two of these are Leoninus, or Léonin (fl. ca. 1163-1190), and Perotinus, or Pérotin (fl. ca. 1200). Léonin is credited with the Magnus liber organi de graduali et antifonario, or Great Book of Organum for the gradual and antiphoner, consisting of two-voice polyphony. Pérotin revised the Magnus liber and composed three- and four-voice organa. These four-voice polyphonic works were the most advanced at the time.

It may be evident by the full name of the Magnus liber that the Proper of the Mass was the primary focus of the earliest polyphonic composition. Graduals and Alleluias make up the bulk of the Magnus liber, although texts of the Office of Vespers were also treated. It was not until the following century when composers turned to the Ordinary of the Mass to exercise their skills.

Perotin: Sederunt Principes. Escuela de Notre Dame. Organum.

Polyphonic settings of the Ordinary

About a century after the time of Pérotin, Guillaume de Machaut (ca. 1300-1377), a French poet and composer, entered the service of the aristocracy in France after some years of travel through Europe as secretary to John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia. By this time, huge changes in rhythmic notation had been adopted, leaving behind the relatively simple modal rhythms of the “Old Art”, or Ars antiqua, of the 13th century. The “New Art”, or Ars nova, employed not only divisions and subdivisions of temporal units but also duple as well as triple groupings, making possible rapid passages and a remarkable variety of syncopation. Additionally, a new and subtle unifying device, called isorhythm, became a favorite way to treat the slow-moving lower voice of compositions, typically a fragment of Gregorian chant.

In isorhythm, a rhythmic pattern, called a talea, for perhaps six to ten notes will be applied to a melodic fragment that does not match the rhythmic pattern in length; the melodic fragment, called a color, may be repeated a number of times, but because the rhythmic pattern does not match it in length, the note values or rhythm of the melody keep shifting, making the melody sound different with each repetition. Think: I am not amused; I am not amused; I am not amused; I am not amused. Here the talea is five units, while the color, represented by the text, is four.)

The 14th Century: Machaut

Machaut wrote a large number of secular pieces, but the work of greatest impact for the future of Mass treatments was his Messe de Nostre Dame (using old French spellings of “Mass” and “Notre”). Earlier polyphonic movements of the Ordinary exist, notably the Mass of Tournai, but Machaut’s landmark work, in the early 1360s, is the first complete setting of the Ordinary of the Mass for four voices by a single composer, and shows not only unifying stylistic devices but also a recurring motto in all the movements.

Machaut - Messe de Notre Dame Ensemble Organum - Dir. Marcel Pérès

Machaut used the range of techniques of the Ars Nova era in this remarkable work. He employed isorhythm in the Gregorian tenors in the Kyrie, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and Ita missa est movements and in all voices in the Amen of the Credo. The rhythmic complexity in the Amens of the Gloria and Credo are stunning tours de force. Harmonically, Machaut conformed to the Ars Nova practice of using a particular progression to create cadences: in what is called a “double leading-tone cadence”, not one but two pitches a fourth or fifth apart rise in parallel motion to a “home” pitch. The distinctive sound is a hallmark of fourteenth century music, revealing an underlying conformity to older rules for “perfection” while pushing toward a harmonic cadence formula suitable for polyphonic composition.

In every way, Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame marks the beginning of a long tradition of composers addressing the Ordinary of the Mass as a challenge to their creative imagination and ingenuity.

In every way, Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame marks the beginning of a long tradition of composers addressing the Ordinary of the Mass as a challenge to their creative imagination and ingenuity.

15th Century: Dufay and the Burgundian Mass

Developments in fifteenth century treatments of the Ordinary bear this out. Quietly working away in the British Isles, composers were creating music with a completely different sound from that of continental composers’ music. The melodies and rhythms were much simpler, and the harmonies were “sweeter”, favoring intervals we call thirds and sixths rather than the dogmatic “perfect” intervals of the continental style. Examples of polyphony, based on England’s Sarum rite, contain triadic or three-pitch harmonies that sound like the common harmonic style of our own time. Even simple folk music and the many religious carols participated in this sound. This tradition informed the work of a significant composer, John Dunstable (or Dunstaple) (1390-1453), whose impact on the music of the continent would change the course of motet composition.

A brief bit of political history is needed here. By Dunstable’s time, there was a war in progress in the territory we know as France and Belgium. The problem was that England and France both laid claim to certain portions of the area. In this argument, the territory of Burgundy was an ally of England. This is the famous Hundred Years’ War, which eventually ended with England ceding her claims and letting France get on with her business. (Joan of Arc assisted in turning the tide in favor of the French.) In the course of this long and complicated conflict, an Englishman, John, the Duke of Bedford, found it necessary to go to his property in Rouen in the region of Burgundy for extended periods of time. Among the duke’s entourage was none other than John Dunstable, who, historians speculate, accompanied his lord.

Among the favorite pastimes of the Burgundian Guillaume Dufay (1397-1474) was the creation of canons.

The word “canon” means a “rule” for treating a melody so as to make it serve in several ways against itself. Today, with our paltry acquaintance with canonic devices, we consider works like “Three Blind Mice” and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” as the standards of the genre. In Dufay’s time, though, composers used a rich palette of canonic devices. For instance, one could use the melody forward and backward at the same time (canon cancrizans or “crab” canon), or right-side-up against upside-down (canon in inversion), or both inverted and reversed at the same time as in its original state. One could begin the melody at two different pitches (an interval canon, such as at the fifth). One could extend the note values (canon in augmentation) or compress the values (canon in diminution), or change the way the primary note value was divided (all of these termed mensuration canons).

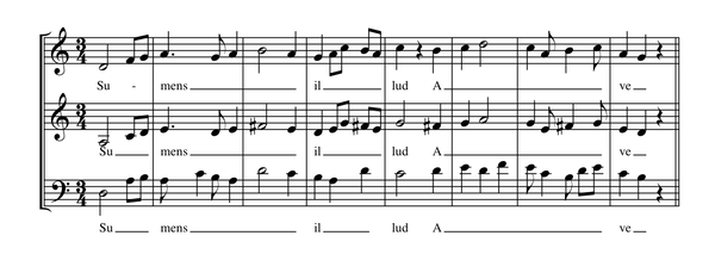

Portion of Du Fay's setting of Ave maris stella, in fauxbourdon. The top line is a paraphrase of the chant; the middle line, designated "fauxbourdon", (not written) follows the top line but exactly a perfect fourth below. The bottom line is often, but not always, a sixth below the top line; it is embellished, and reaches cadences on the octave.

Guillaume Dufay - Ave Maris Stella

Pomerium - Conductor, Alexander Blachly

Pomerium - Conductor, Alexander Blachly

With any of these options, the composer ratcheted up the game by giving curious little clues to the solution of the canonic puzzle: “Go forward full and return half”! This was an actual instruction by Dufay in the Agnus Dei movement of his Missa L’homme armé. What does the instruction mean? Well, perform the melody in its full note values in regular forward progression, then perform it backwards at half the original note values. This kind of puzzle or game marked the Renaissance attitude of celebrating the intellect, the ability of the human being to reason out difficult mathematical relationships.

Dufay's Missa L'homme armé - Agnus Dei

The Hilliard Ensemble

The Hilliard Ensemble

Another feature of the polyphonic Mass settings of the fifteenth century was its thematic unity. In some cases, a fragment or motto at the beginning of each movement gave the whole its coherence. In other cases, composers used a known melody in the tenor as the foundation for the entire Mass. The formal term for this foundation melody, no matter its source, is cantus firmus—literally, an established song, or borrowed melody. The cantus firmus formed the tenor voice—the voice that earlier had held the chant melody. (Remember, at this time, “tenor” was not a vocal category but simply the voice part that “held” the foundation melody, the cantus firmus.) The cantus firmus might be a Gregorian chant, but often it was not. In fact, not only was the cantus firmus often not Gregorian chant, it was very often a secular tune! The name of the cantus firmus melody lent its name to the entire mass; thus, the Missa L’homme armé mentioned above was a Mass (Missa) constructed on the song, “L’homme armé”, “The Armed Man”. Such a Mass was termed a “cantus-firmus Mass” or “tenor Mass”.

“The Armed Man”, technically a secular chanson, was widely known in the fifteenth century, a time when the Hundred Years’ War had strained the endurance of the two contending nations, France and England. The chanson itself has a short and memorable text in Old French:

L’homme, l’homme, l’homme armé, l’homme armé,

The man, the man, the armed man, the armed man,

L’homme armé doibt on doubter, doibt on doubter.

The armed man ought to be feared, ought to be feared.

On a fait partout crier

It has been everywhere proclaimed

Que chascun se viengne armer

That everyone should arm himself

D’un haubregon de fer.

With a mail coat of iron.

L’homme, etc. (The first two lines return.)

The man, the man, the armed man, the armed man,

L’homme armé doibt on doubter, doibt on doubter.

The armed man ought to be feared, ought to be feared.

On a fait partout crier

It has been everywhere proclaimed

Que chascun se viengne armer

That everyone should arm himself

D’un haubregon de fer.

With a mail coat of iron.

L’homme, etc. (The first two lines return.)

Dufay's Missa L'Homme Armé

Oxford Camerata - Jeremy Summerly, conductor

Oxford Camerata - Jeremy Summerly, conductor

Dufay’s successors Johannes Ockeghem, Josquin des Pres and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, among others, adopted this pop tune as the tenor for their Mass settings. And from Dufay’s time onward through the Renaissance, numerous Masses were composed around a wide selection of secular tunes.

Finally, in the fifteenth century composers adopted the convention of a four-voice texture to supersede the earlier three-voice texture. The tenor was situated in the next-to-lowest position, with a contra-tenor bassus (a “low voice against the tenor”) below it; above the tenor was the contra-tenor altus (a “high voice against the tenor”), and above that a “superius”. Here are the roots of our current usage of the voice part designations “tenor”, “bass”, and “alto”. The lowest voice part not only extended the aural range downward but began to function as a harmonic foundation.

Late 15th Century and early 16th Century Franco-Flemish Composers

Guillaume Dufay, a Burgundian composer, is considered to be on the “cusp” of the Renaissance. Successive generations from northern France and the low countries, called Franco-Flemish composers, were decidedly of the Renaissance. They expanded not only vocal ranges and numbers of voices in their Mass settings but also achieved technical wonders in their Masses.

Technical devices were especially interesting among the Franco-Flemish composers. Jean de Ockeghem (ca. 1450-1497), for instance, produced a remarkable Mass setting in which changes in time values were the crux of the structure; in the Sanctus of this Prolation Mass, Ockeghem invented a double canon in which two voices using one melody worked in two different sets of time values while the remaining two voices used another melody in different time values—and, astonishingly, the resulting harmonies are gorgeous!

Ockeghem's Missa Prolationum | Sanctus

Musica Ficta

Musica Ficta

The Masses of Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450-1521) are also technically remarkable. In his Missa Hercules dux Ferrarieae, for instance, he devised a unique tenor by taking the vowels from the name and title of the Duke of Ferrara and casting them as solfeggio syllables, Re, Ut (the old “Do”), Re, Ut, Re, Fa, Mi, Re, or D, C, D, C, D, F, E, D. In his Missa L’homme armé, he transposed the melody on rising degrees of the scale for each of the movements. In all of the cases of complexity and technical ingenuity, the beauty of the harmony and the smoothness of the flow of sounds is never disturbed; the Renaissance ethos of “art” obscuring the “artifice”, or beauty obscuring technique, is maintained.

Josquin des Prez - Missa Hercules dux Ferrariae

Hilliard Ensemble

Hilliard Ensemble

Progressively greater extensions of vocal range appeared in Masses by Johannes Ockeghem (ca. 1420-1490), Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450-1521), Heinrich Isaac (ca. 1450-1517)—with up to six voice parts, and Orlando di Lasso (ca. 1532-1594) and the Italian Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (ca. 1525-1594)—with up to eight voice parts.

The Impact of the Counter-Reformation

The increasingly complex working of the Mass through the sixteenth century was brought to a halt as an indirect result of the Protestant Reformation. Facing a severe challenge from the Reformation movement to the institution of the church, Pope Paul III convened a church council at Trent (1545-63) to determine how to deal with the problem.

A Counter-Reformation movement rested on reforms within the church and reconversion efforts from groups such as the Society of Jesus. During the years of the Council, the Italian-born Palestrina was appointed Maestro of the Cappella Giulia at St. Peter’s in Rome, and a year later admitted to the Pope’s official musical chapel, the Cappella Sistina, where he would have been a singer. During his time there, he and the other singers, preparing for Holy Week, heard the direction of then-pope Marcellus II, that words needed to be clearly understood and the music should fit the occasion. Not ten years later, the Council wrapped up its business. Amid all of their deliberations, they came up with only one musical directive: to keep “lascivious or impure” elements out of sacred works. There was some discussion about polyphony as an impediment to textual clarity, but no action was ever taken to abolish it. Polyphony, however, remained the focus of intense controversy as an ongoing concern among reformers. It was of utmost importance to them that the tenets expressed within the Gloria and Credo be clearly audible. And in this matter, Palestrina’s famous Missa Papae Marcelli--Pope Marcellus Mass—is relevant.

Palestrina's Missa Papae Marcelli | Kyrie

Oxford Camerata

Oxford Camerata

By the time the Council of Trent ended, Palestrina had been released from the Sistine Chapel for being married, left his next position at St. John Lateran, and taken a job at Santa Maria Maggiore that would last until 1571. During Palestrina’s Sta. Maria Maggiore years, a post-Council commission instituted a trial to determine whether textual clarity could be achieved in a polyphonic Mass. The trial was indeed held, in April 1565. A Mass by Vincenzo Ruffo was performed for the trial, but there is no evidence that Palestrina’s Mass was performed—or that it wasn’t performed. Scholars are not agreed on when Palestrina composed that Mass; it might have been in the mid 1550s or as late as 1562. What is clear, though, is that this Mass and one other he is known to have composed in 1568 to fulfill the clarity goal have a simpler texture and more comprehensible alignment of words than previous polyphonic masses.

The style Palestrina established in the Pope Marcellus Mass became the benchmark for Mass settings in the late Renaissance. The similar rhythms of the six voice parts, using a limited variety of note values and even occasional chord-like simultaneous motion of the voices, allowed a remarkable textual clarity. Harmonic progressions became evident, revealing in Palestrina’s music a weakening of the system of modal harmonies of the Medieval Era and an emerging sense of a tonal center. Imitative entrances, a feature of Josquin’s polyphony earlier in the century, were keenly audible but avoided the cleverness of canon. The individual melody lines themselves sustained a beautiful arch. Dissonance was carefully approached and resolved without any sense of awkwardness. The totality of the sound lifted the spirit, calmed the senses, and conveyed a reverent attitude. For very good reason Palestrina’s music was studied over the next centuries as a model of exquisite control of materials to achieve an extraordinary sense of spirituality. And for very good reason, few composers after Palestrina walked in his compositional shoes.

Baroque Era

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Mass composition changed considerably. For one thing, the emerging Baroque style relied on instrumental accompaniment. The age of the unaccompanied polyphonic setting of the Ordinary had largely passed. Composers such as Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) were choosing shorter texts capable of greater dramatic interpretation, even for sacred settings; these would fall into the category of motet. (See Essay: Motet)

There are several settings of the Ordinary by Monteverdi, but many more motets on Proper texts. Likewise through the Baroque era, composers seemed less interested in composing the Ordinary, although in fact composers in virtually every center produced Masses. Even Bach’s great B-Minor Mass, while decidedly contrapuntal, was not the product of a concentrated time frame for a unified presentation but rather an assembled construct of movements composed over decades.

Post-Baroque Era

After the middle of the eighteenth century there was again a flowering of settings of the Ordinary, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Franz Joseph Haydn (1733-1809), Michael Haydn (1737–1806), and to a lesser extent Franz Schubert (1797-1828). Yet in none of the Masses of the 18th and early 19th century was the style strictly polyphonic; by then, homophony (chordal structure) prevailed, and almost always the now-established tonal system of harmony dispensed with old modal harmonies.

|

Mozart's Great Mass in C minor, K. 427

Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Markus Stenz, conductor Sophie Harmsen, soprano | Lenneke Ruiten, soprano | Attilio Glaser, tenor | Morgan Pearse, bass |

|

Schubert's Mass No. 6 in E flat major, D. 950

Chorus Viennensis, Wiener Sängerknaben Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Bruno Weil Stefan Preyer, soprano | Thomas Weinhappel, alto | Jörg Hering, tenor | Harry van der Kamp, bass |

19th Century: Romantic Tradition

Many of the Masses of the 19th century Romantic tradition tended to be large concert works rather than part of a religious service. Enormous forces necessary for Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Requiem dwarf those for Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Missa Solemnis. But a reform in church music driven by the Cecilian movement impelled some composers to work in a more antique style. An arch-Romantic, Franz Liszt (1811-1886) contributed a very large setting of the Ordinary but then also smaller settings.

When the devout Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) gave his attention to the Ordinary of the Mass in the second half of the century, he first composed large settings of the text; then, inspired by the Cecilian movement that had been underway for some time, he returned to the old model of the Renaissance—Palestrina.

20th Century

Twentieth-century Mass composition seems to have continued in the bifurcated manner of the 19th century. Dramatic, large works such as Benjamin Britten’s unusual mixture of the Latin Requiem with moving secular poetry in English, in his War Requiem, contrast against works in more modest style, such as those for service use by Edmund Rubbra.

There are Mass settings drawing on non-European cultures, such as the Missa luba and Missa criolla. Igor Stravinsky’s Mass (1948), regarded as perhaps the greatest work of the century, is an austere concert work for chorus and ten wind instruments. Suffice it to say, Mass composition has not been extinguished (witness Leonard Bernstein's 1971 Mass), but, as might be expected, has expanded its reach to all possible circumstances using any and all possible resources.

21st Century

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.