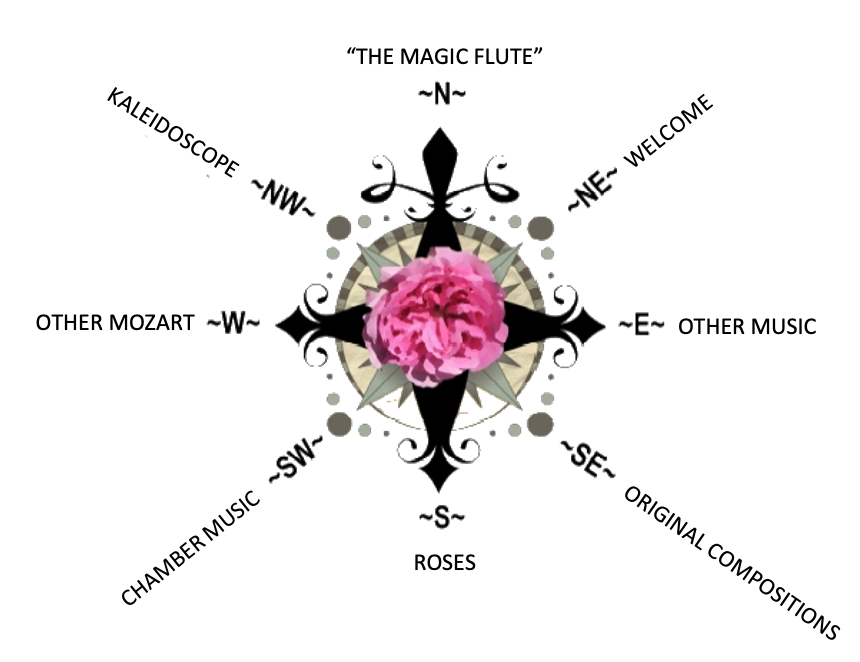

- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

GRACE WOODS MUSIC SESSION: MAY 23, 2022

Guest Essay: Why Art?

by David Schwartz Ph.D.

by David Schwartz Ph.D.

Exposure to art makes us better people. I can remember frequently being told this throughout my primary education. Often the message came in the form of a stern reprimand, such as from language arts teachers pushing us to do our poetry homework. Now, that message is most frequently conveyed by arts organizations appealing for donations. Experiencing museums lined with Matisse and Renoir, concert halls ringing out Mozart and Brahms, theaters echoing Shakespeare and Ibsen, along with endless volumes of works by Emerson, Longfellow, Mark Twain and Fitzgerald, somehow contributes to our overall well-being, and adds value and quality to us as individuals. Exposure to culture is supposed to do this.

I have thought of myself as an artist most of my life and it never made sense to me. How does exposure to great works of art make me anything other than an informed conversationalist? I love Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in D Minor, and no matter how much I listen to it, I have never felt like a better person for it. I have spent countless hours completely immersed in some of the great masterpieces of human culture. Inspired by them, I have spent countless hours trying to create my own works of art. But I didn’t truly understand how profoundly art had influenced me until recently when I helped care for my friend who had cancer and was terminal. And art’s lesson wouldn’t be anything I anticipated.

Richard del Val was a dear friend and a brilliant musician who, in January 2019, was diagnosed with brain cancer, a glioblastoma multiforme, or GBM. As I would learn, GBM is as virulent and as fatal as cancer gets. That January his prognosis was fewer than six months.

I spent as much time with Richard as his remaining days allowed, both as his friend and as a care giver. I helped him to and from five weeks of radiation therapy treatments and I also helped his sister, who was his primary care giver, with his moment to moment needs until the end. Richard spent the last few weeks of his life in my house, where he died August 21, 2019, around 7pm. He was 56 years old.

We have all been told that music heals. It couldn’t soothe Richard. As the weeks went by, Richard slept more and more. And when he was awake, the growing brain tumor didn’t allow his mind to function well enough for him to keep his balance to walk, let alone comprehend and reflect on complex works of art from any medium. In his broken brain, music became jumbled and irritating noise. No music was played during the last three months of Richard’s life. It was particularly quiet during his last few weeks. I watched as music disappeared and became irrelevant for Richard, one of the most gifted musicians I will ever know. It made me, a musician, an artist, struggle with questions about whether music is really nothing more than a temporary diversion for the senses, and that it has no inherent value outside of that.

Two nights before Richard died, the rapidly growing mass in his brain was creating tremendous pressure in his head. His left eye had started to become distended, and his discomfort was increasing palpably. The next morning, with the supervision of Hospice, we began to administer liquid morphine orally to Richard. His last word was “OK’ when his sister gave him the first drops of the liquid and, cupping his cheek with her hand, assured him that it would help him sleep. Every hour after that, his sister and I took turns giving Richard morphine for his pain.

At 2am on the day that Richard died it was my turn to administer the morphine. I walked through the dark and very quiet house to the kitchen. There I filled the eye dropper with the prescribed amount of the clear liquid. In the room next to the kitchen Richard was unconscious and breathing slowly and deeply. I leaned in and slid the eye dropper into the right side of his mouth, between his cheek and his teeth, and carefully pushed the morphine into his mouth.

As Richard breathed and the liquid slid into his throat, I heard gurgling. It is peculiar what we think, sometimes, in difficult situations. For a moment I was panicked that he was choking on the liquid and that it might kill him. But, when the gurgling didn’t stop and it continued with each breath, from somewhere in my past a book, or poem, or play I had once read reached out to me and steadied me. I was hearing the so called “death rattle”, that now anonymous work of literature reminded me. What I was witnessing firsthand, I had before witnessed vicariously through literature. I knew what I was experiencing and that provided me with a tremendous amount of comfort. At that moment it was the one thing I needed above all, alone, next to my dying friend who was struggling to breath.

Later that evening after Richard died, I watched the color of his hands change, his incredibly virtuosic hands, as the blood settled, and the warmth left him. They had become white, like marble. And watching this transformation in my dead friend, I was reminded of Michelangelo’s Pieta and the hands on that dead body, held close in the arms of his grief-stricken mother. Again I found comfort in a situation I had never before experienced, as my mind superimposed those marble hands over Richard’s.

In the days following Richard’s death I couldn’t help but to reflect on the death rattle and the marble hands. And it prompted a fountain of reflections about things that had happened over the course of Richard’s illness. There are a lot of awful memories that are part and parcel of caring for a terminal patient. Among other things, you watch as your loved one tries to maintain their dignity while their body stops working. It can be heart wrenching. I wondered how I had been able to maintain my composure in the face of so many unfamiliar and quite terrible experiences. I realized it was art that had been the messenger and had prepared the way for those difficult days.

Art is not unlike virtual reality. Great works of art lead us to temporarily immerse ourselves in thoughts and emotions and situations, both real and imagined. And by doing such, it gives us practice for encountering these instances in our own lives. It is easy to imagine the thoughts of that desperate father on horseback rushing his sick and hallucinating child for medical attention when we listen to Franz Schubert’s “Erlkonig.” We can all relate to the futility in Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven”, where an anguished man desperately seeks the knowledge and understanding to assuage his inconsolable grief over the loss of his beloved. Thomas Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic,” puts us in the operating room, with those physicians, and with the patient’s disconsolate wife. We have all been George Bailey, questioning the value of our lives. We have shared existential anguish with Munch’s The Scream. We have looked through eyes filled with abject hopelessness gazing out at Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows. As these artists have been inspired from their experiences, both sensorily and psychologically, so too have they conveyed elements of those experiences through their work. And if we let them, we can immerse ourselves in what they are sharing with us. We can put ourselves in their shoes and hear what these artists are saying and feel what they are feeling, and we can learn. These temporary immersions can inform us, prepare us, and help to strengthen and shape us as feeling and thinking beings.

The transition from being a caregiver to the ‘after’, is abrupt. For 8 months we cared for Richard and anticipated his death. Our lives revolved around the practice of caring for him and that morbid anticipation. All other human and daily endeavors became insignificant during this time. And then suddenly, he is gone, and it is over, and life returns to normal, sort of. I found myself in a bit of a fog. Looking for my own understanding about what I had experienced, I found myself pouring through my old philosophy books, books about aesthetics, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, and YouTube. I was reminded that commentaries about the necessity for art in our daily lives is nearly as old as art itself.

Nearly every major philosopher has addressed the need for art in our daily lives. For example, Aristotle viewed art as a catharsis and that attending theater can help us ‘release’ unwanted emotions, keeping us psychologically balanced. Immanuel Kant believed that art helps us develop and cultivate our minds, allowing us to be more expressive and effective communicators. William James believed that art could provide moral instruction. Indeed, views on the need for art are as varied as the art world itself.

This article’s contribution to the arguments for the importance of the arts is not novel. But what I do hope to contribute is a reminder that art is not simply a pastime for embracing aesthetic pleasure. It can play an enormous role in our development as strong and empathetic individuals. Quite simply, art allows us to practice being human, safely.

As one last parting thought, I was fascinated to learn anecdotally that there is some evidence to show that medical students who take art appreciation classes tend to be better diagnosticians than those who do not. This is without question the efficacy of the arts as teacher, of the arts as experience, and of the arts as virtual reality. I am grateful for all of the artists from each of the fields of art that have touched me. They have shared life stories with me, and they have bettered me as a person, and when it came time to act and help my friend Richard del Val transition from life to death, I didn’t realize that the world of art had been training me throughout my life for such a thing. For me, and I can say this without any reservations, the arts gave me a gift that I didn’t know I was receiving. Throughout my lifelong relationship with the arts, the arts were quietly giving me experiences that would serve me during as difficult an episode as I may ever know.

I have thought of myself as an artist most of my life and it never made sense to me. How does exposure to great works of art make me anything other than an informed conversationalist? I love Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in D Minor, and no matter how much I listen to it, I have never felt like a better person for it. I have spent countless hours completely immersed in some of the great masterpieces of human culture. Inspired by them, I have spent countless hours trying to create my own works of art. But I didn’t truly understand how profoundly art had influenced me until recently when I helped care for my friend who had cancer and was terminal. And art’s lesson wouldn’t be anything I anticipated.

Richard del Val was a dear friend and a brilliant musician who, in January 2019, was diagnosed with brain cancer, a glioblastoma multiforme, or GBM. As I would learn, GBM is as virulent and as fatal as cancer gets. That January his prognosis was fewer than six months.

I spent as much time with Richard as his remaining days allowed, both as his friend and as a care giver. I helped him to and from five weeks of radiation therapy treatments and I also helped his sister, who was his primary care giver, with his moment to moment needs until the end. Richard spent the last few weeks of his life in my house, where he died August 21, 2019, around 7pm. He was 56 years old.

We have all been told that music heals. It couldn’t soothe Richard. As the weeks went by, Richard slept more and more. And when he was awake, the growing brain tumor didn’t allow his mind to function well enough for him to keep his balance to walk, let alone comprehend and reflect on complex works of art from any medium. In his broken brain, music became jumbled and irritating noise. No music was played during the last three months of Richard’s life. It was particularly quiet during his last few weeks. I watched as music disappeared and became irrelevant for Richard, one of the most gifted musicians I will ever know. It made me, a musician, an artist, struggle with questions about whether music is really nothing more than a temporary diversion for the senses, and that it has no inherent value outside of that.

Two nights before Richard died, the rapidly growing mass in his brain was creating tremendous pressure in his head. His left eye had started to become distended, and his discomfort was increasing palpably. The next morning, with the supervision of Hospice, we began to administer liquid morphine orally to Richard. His last word was “OK’ when his sister gave him the first drops of the liquid and, cupping his cheek with her hand, assured him that it would help him sleep. Every hour after that, his sister and I took turns giving Richard morphine for his pain.

At 2am on the day that Richard died it was my turn to administer the morphine. I walked through the dark and very quiet house to the kitchen. There I filled the eye dropper with the prescribed amount of the clear liquid. In the room next to the kitchen Richard was unconscious and breathing slowly and deeply. I leaned in and slid the eye dropper into the right side of his mouth, between his cheek and his teeth, and carefully pushed the morphine into his mouth.

As Richard breathed and the liquid slid into his throat, I heard gurgling. It is peculiar what we think, sometimes, in difficult situations. For a moment I was panicked that he was choking on the liquid and that it might kill him. But, when the gurgling didn’t stop and it continued with each breath, from somewhere in my past a book, or poem, or play I had once read reached out to me and steadied me. I was hearing the so called “death rattle”, that now anonymous work of literature reminded me. What I was witnessing firsthand, I had before witnessed vicariously through literature. I knew what I was experiencing and that provided me with a tremendous amount of comfort. At that moment it was the one thing I needed above all, alone, next to my dying friend who was struggling to breath.

Later that evening after Richard died, I watched the color of his hands change, his incredibly virtuosic hands, as the blood settled, and the warmth left him. They had become white, like marble. And watching this transformation in my dead friend, I was reminded of Michelangelo’s Pieta and the hands on that dead body, held close in the arms of his grief-stricken mother. Again I found comfort in a situation I had never before experienced, as my mind superimposed those marble hands over Richard’s.

In the days following Richard’s death I couldn’t help but to reflect on the death rattle and the marble hands. And it prompted a fountain of reflections about things that had happened over the course of Richard’s illness. There are a lot of awful memories that are part and parcel of caring for a terminal patient. Among other things, you watch as your loved one tries to maintain their dignity while their body stops working. It can be heart wrenching. I wondered how I had been able to maintain my composure in the face of so many unfamiliar and quite terrible experiences. I realized it was art that had been the messenger and had prepared the way for those difficult days.

Art is not unlike virtual reality. Great works of art lead us to temporarily immerse ourselves in thoughts and emotions and situations, both real and imagined. And by doing such, it gives us practice for encountering these instances in our own lives. It is easy to imagine the thoughts of that desperate father on horseback rushing his sick and hallucinating child for medical attention when we listen to Franz Schubert’s “Erlkonig.” We can all relate to the futility in Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven”, where an anguished man desperately seeks the knowledge and understanding to assuage his inconsolable grief over the loss of his beloved. Thomas Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic,” puts us in the operating room, with those physicians, and with the patient’s disconsolate wife. We have all been George Bailey, questioning the value of our lives. We have shared existential anguish with Munch’s The Scream. We have looked through eyes filled with abject hopelessness gazing out at Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows. As these artists have been inspired from their experiences, both sensorily and psychologically, so too have they conveyed elements of those experiences through their work. And if we let them, we can immerse ourselves in what they are sharing with us. We can put ourselves in their shoes and hear what these artists are saying and feel what they are feeling, and we can learn. These temporary immersions can inform us, prepare us, and help to strengthen and shape us as feeling and thinking beings.

The transition from being a caregiver to the ‘after’, is abrupt. For 8 months we cared for Richard and anticipated his death. Our lives revolved around the practice of caring for him and that morbid anticipation. All other human and daily endeavors became insignificant during this time. And then suddenly, he is gone, and it is over, and life returns to normal, sort of. I found myself in a bit of a fog. Looking for my own understanding about what I had experienced, I found myself pouring through my old philosophy books, books about aesthetics, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, and YouTube. I was reminded that commentaries about the necessity for art in our daily lives is nearly as old as art itself.

Nearly every major philosopher has addressed the need for art in our daily lives. For example, Aristotle viewed art as a catharsis and that attending theater can help us ‘release’ unwanted emotions, keeping us psychologically balanced. Immanuel Kant believed that art helps us develop and cultivate our minds, allowing us to be more expressive and effective communicators. William James believed that art could provide moral instruction. Indeed, views on the need for art are as varied as the art world itself.

This article’s contribution to the arguments for the importance of the arts is not novel. But what I do hope to contribute is a reminder that art is not simply a pastime for embracing aesthetic pleasure. It can play an enormous role in our development as strong and empathetic individuals. Quite simply, art allows us to practice being human, safely.

As one last parting thought, I was fascinated to learn anecdotally that there is some evidence to show that medical students who take art appreciation classes tend to be better diagnosticians than those who do not. This is without question the efficacy of the arts as teacher, of the arts as experience, and of the arts as virtual reality. I am grateful for all of the artists from each of the fields of art that have touched me. They have shared life stories with me, and they have bettered me as a person, and when it came time to act and help my friend Richard del Val transition from life to death, I didn’t realize that the world of art had been training me throughout my life for such a thing. For me, and I can say this without any reservations, the arts gave me a gift that I didn’t know I was receiving. Throughout my lifelong relationship with the arts, the arts were quietly giving me experiences that would serve me during as difficult an episode as I may ever know.

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.