- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

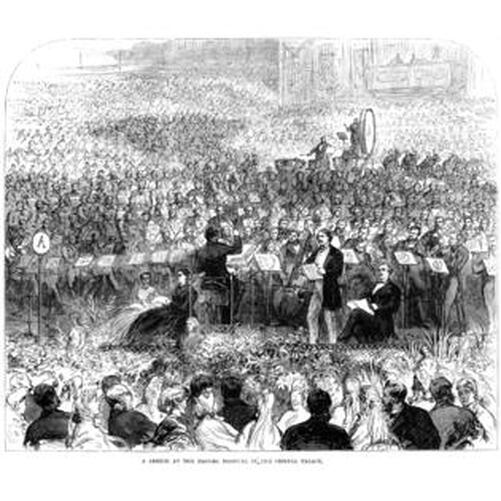

Handel’s Messiah

by Judith Eckelmeyuer

(Grace Woods Music Session, Deceember 12, 2022)

Handel, that remarkable composer of so much English music, was born in Halle, then in Saxony, in 1685. He received his musical training there and in Hamburg before journeying to Italy early in 1707 to expand his experience. For the three years he was there, Handel absorbed the style that had made Italy the premiere center of Baroque composition (despite France’s rivalry). Returning to Germany, he accepted the appointment to serve the Elector of Hanover, George. During this period of service, Handel visited England twice, earning an early reputation there as a master of the contemporary style.

At the death of Queen Anne in 1714, none other than George of Hanover, to whom Handel was still obligated, succeeded to the throne of England. The rapprochement between Handel and King George I took more than a year, but in the end the king maintained Handel in his service.

Handel had been creating music in and for England for nearly 30 years before he wrote Messiah in 1741. He had devoted a good portion of his career to composing operas in the Italian style to entertain the social elite at theaters which he directed in London. He had also composed many choral works for the nobility, for occasions such as coronations, entertainments, state celebrations and funerals, and instrumental music for both court and church. And he had already ventured into the sphere of the oratorio with considerable success, particularly after Pepusch and Gay’s Beggar’s Opera in 1728 undercut the popularity of Italian opera with its parody of the opera seria and its use of a libretto entirely in English.

As a result of the changing public taste, along with production problems such as outright brawling between rival singers and increasing financial demands by the singers, he saw his opera company decline and finally fall into bankruptcy in 1737. He also suffered occasional attacks of paralysis which weakened him, interrupted his work, and led him to return to Germany for a time to recover his health.

When he returned to England, Handel’s focus shifted almost entirely from the opera to the oratorio. This made sense financially. He could draw on his compositional skill without the expenses of theater machinery, props, costumes, and drama rehearsals, since oratorio, unlike opera, was not a staged work.

Messiah is a unique oratorio, for it is neither history nor dramatic tale nor philosophy. All of its text is scripture, from both Old and New Testaments, selected and sequenced by Charles Jennens, a librettist with whom Handel had collaborated previously. Its subject is the Anointed One, the Expected One, the promised royal and spiritual leader of the Jewish people. A peculiar feature of the texts which Jennens selected, however, is that in only one instance is the name Jesus cited, and that is very near the end of the oratorio. Thus the oratorio takes on a new role: a reflection or contemplation of the nature of the Anointed One rather than a celebration of a particular named figure.

It is the abstractness of Messiah’s text that may in the long run have made it possible for Handel to offer this oratorio during Lent in a secular setting–a theater in Dublin–to raise money for several charitable institutions.

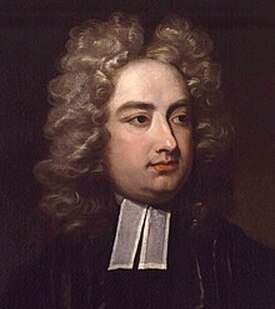

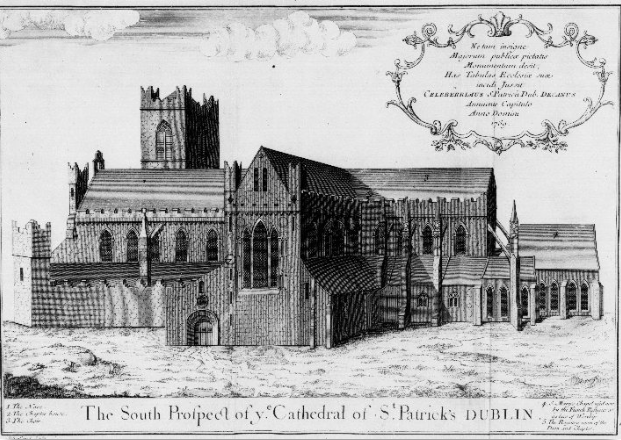

Even so, Jonathan Swift, the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, considered the performance of sacred text outside a sacred setting so abominable that he published a notice forbidding any church related person to participate in any way, or even attend any performance of the work, on pain of punishment by the church. Swift must have relented in the end, though, because singers from the cathedral choirs appeared in the premiere performance on April 13, 1742. The chorus, according to the Grove Dictionary entry for Handel, there were probaby no more than 20 singers, consisted of boys and men from the cathedral choir, with the soloists joining them in choruses.

Messiah continued to be a favorite in Handel’s time. Different performances in different locations required the composer to prepare new arias or recast some of the existing music for different singers with different voice ranges. None of these changes dampened the public’s enthusiasm for the work.

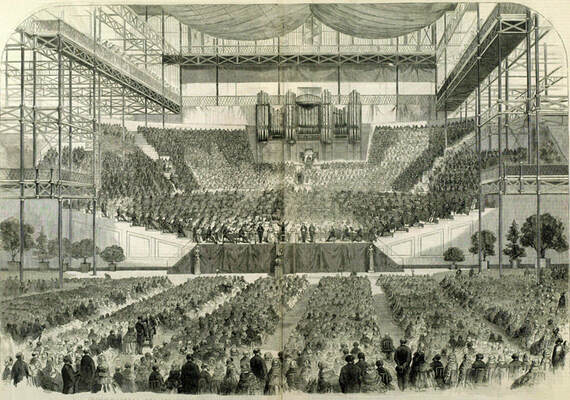

In fact, if anything, Messiah transcended its time so successfully that composers like Mozart and any number of conductors adapted it for performances in their own day. It’s safe to say that Handel would barely recognize his work in some of those adaptations: ponderous tempos that accommodated a chorus of a thousand singers; massive reorchestrations for large ensembles of modern instruments; wholly un-baroque performance style for the singers and the instrumentalists; and of course no consistent pattern for the choice of arias and choruses. Yet in spite of how musicians and adoring fans have encountered it over the centuries, Messiah remains vitally alive in the music scene and the consciousness of our culture today.

I think we will benefit from a short walk alongside the music, as if in a nature reserve, examining some details, which are explained below. These devices were common coin for Baroque-era composers, who saw their art as an extension of spoken rhetoric by which they used certain conventions to convey meaning in music and move the emotions of the audience (the so-called “doctrine of affects”). These details are usually lost on listeners today. Our consideration of Handel’s music will explore some of these details to adjust our imagination to his “language” and hear his “take” on the text of Part I, the so-called Christmas portion, and the “Hallelujah” chorus.

French overture: invented in the second half of the 17th century by Louis XIV’s composer Jean-Philip Lully, it begins with a slow homophonic section with distinctly uneven notes (long, very short), moves to a fast fugue-like polyphonic section, and concludes slowly, again with the uneven rhythm.

Counterpoint, polyphony: more than one melodic line at a time.

Homophony: one melodic line supported by harmonic accompaniment.

Hammer strokes: strong or accented separated notes or chords.

Recitative—Dry and Accompanied: a passage for vocal soloist, generally a prose text without repetition.

Dry recitative: very minimal chordal punctuation by accompanying instruments.

Accompanied recitative: a much more melodic presentation, often with repeated sections of text, and a more ample orchestral accompaniment.

Aria (air): an extended vocal solo with orchestra accompaniment, on a poetic text. It is typically in three sections; the first and third have the same text and music, but instead of repeating the first section exactly, the soloist usually improvises some ornaments to enrich the poetic content. The second section has new text and music.

Word painting: a technique in which the music represents a specific word—rising melody on the word “arise”, for example.

Walking bass: a device for the orchestra’s bass instruments in regular notes, usually in a stepwise pattern, at a walking pace through a section.

Continuo: the omnipresent accompaniment group underlying almost all music in the Baroque (fugues are one exception). The group consists of a bass instrument providing a foundation line of music supporting a harmony-producing instrument. A typical continuo might consist of a viola da gamba and harpsichord, or a bassoon and lute. The organ contains within itself the elements needed to produce a continuo. “Continuo” refers to both the performing group and the music they perform; it forms the foundation for all other musical material above it.

French overture: invented in the second half of the 17th century by Louis XIV’s composer Jean-Philip Lully, it begins with a slow homophonic section with distinctly uneven notes (long, very short), moves to a fast fugue-like polyphonic section, and concludes slowly, again with the uneven rhythm.

Counterpoint, polyphony: more than one melodic line at a time.

Homophony: one melodic line supported by harmonic accompaniment.

Hammer strokes: strong or accented separated notes or chords.

Recitative—Dry and Accompanied: a passage for vocal soloist, generally a prose text without repetition.

Dry recitative: very minimal chordal punctuation by accompanying instruments.

Accompanied recitative: a much more melodic presentation, often with repeated sections of text, and a more ample orchestral accompaniment.

Aria (air): an extended vocal solo with orchestra accompaniment, on a poetic text. It is typically in three sections; the first and third have the same text and music, but instead of repeating the first section exactly, the soloist usually improvises some ornaments to enrich the poetic content. The second section has new text and music.

Word painting: a technique in which the music represents a specific word—rising melody on the word “arise”, for example.

Walking bass: a device for the orchestra’s bass instruments in regular notes, usually in a stepwise pattern, at a walking pace through a section.

Continuo: the omnipresent accompaniment group underlying almost all music in the Baroque (fugues are one exception). The group consists of a bass instrument providing a foundation line of music supporting a harmony-producing instrument. A typical continuo might consist of a viola da gamba and harpsichord, or a bassoon and lute. The organ contains within itself the elements needed to produce a continuo. “Continuo” refers to both the performing group and the music they perform; it forms the foundation for all other musical material above it.

"Handel's Messiah in Grace Cathedral" (complete) | American Bach Soloists

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.