- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

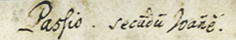

Bach: The Passion According to St. John

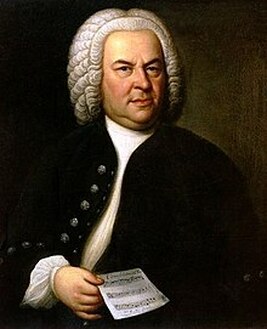

The Passion According to St. John by J.S. Bach

Good Friday Concert Program Notes

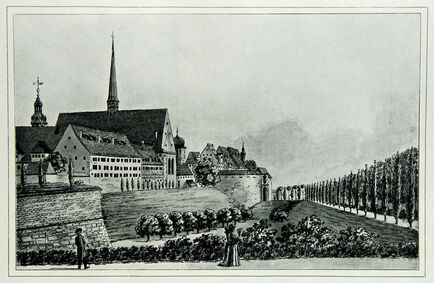

Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland, Ohio

April 3, 2015

“Lord, Lord, Lord, our ruler…show us by your Passion that you,

the true Son of God, have…even in the greatest lowliness, been glorified.”

the true Son of God, have…even in the greatest lowliness, been glorified.”

This startling appeal in the opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s first setting of the Passion According to St. John in 1724 reveals the message of the entire work: Jesus the Messiah, glorified in the abasement of his torture and crucifixion, is worthy through humiliation to reign as King; further, his crucifixion, concluding his work on earth, is victory over death and the redemption of the world. The tension set up in paradoxes of simultaneous opposites, inverted and crossed relationships, and the patent ironies of St. John’s text runs through Bach’s music to form a memorable yet disturbing work that amplifies the message in St. John’s gospel.

What is a Passion?

As a specialized type of oratorio, a passion in the 18th century had all the ingredients common to operas of the time except for the staged action and scenery. Conveying the text from St. John’s gospel (in Martin Luther’s translation) are a special tenor soloist, the Evangelist, who sings the words of the gospel author, and soloists taking the role of the various characters in the story (Jesus, Pilate, Peter, servants, etc.). A four-part choir sings the role of the “crowd” (called a turba), in the various roles of Jewish religious authorities and soldiers, Jewish citizens, and Roman soldiers. There are also non-scriptural solo recitatives and arias, with new texts by an unknown writer, that reflect on events in the gospel’s text. Two large, non-scriptural choral movements with full orchestra accompaniment frame the whole work. And, as with his cantatas for church services, Bach selected and incorporated a number of chorales (hymns) throughout the work. The solo arias and chorales function as reflective moments representing the congregation’s supposed reaction to the story. The congregation could join in singing at least the melody line of the chorales, with which they were certainly familiar; the unusual harmonies would be left to the choir and accompanying instruments to perform. A chorale ends Part I, another begins Part II, and still another follows the last grand chorus to end the work. In one unique movement, a chorale undergirds and complements a meditative bass solo. The instrumental forces required are 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 oboes d’amore, 2 oboes da caccia, 2 violas d’amore, viola da gamba, lute, organ, harpsichord, strings, and continuo.

Bach’s Passion setting was not a meditative entertainment performed in a secular venue, as was Handel’s Messiah. Rather, he composed it as a part of the Lutheran church service for Good Friday, April 7, 1724, at Leipzig’s St. Nicholas Church. The full service began with a hymn, followed by the first part of the Passion. Next there was a sermon, followed by the second part of the Passion, a motet, a verse and collect, benediction, and concluding hymn (Robin A. Leaver, “The mature vocal works and their theological and liturgical context in Bach”, ed. John Butt, 1997, 99). (This Passion runs about 1½ hours; how long must that service have been?) Part I of the Passion presents John’s gospel from the beginning of Chapter 18 through verse 27, telling of Jesus’s being captured in the garden and taken before Annas and the High Priest Caiaphas, and Peter’s denial of Jesus. Part II continues from verse 28 through the whole of Chapter 19, Jesus’s trial before Pilate, his crucifixion, and burial. Continuing a tradition begun in the 17th century, Bach also interpolated several verses borrowed from St. Matthew’s gospel telling of Peter’s weeping after his denial of Jesus, and the rending of the Temple veil, the opening of graves, and the earthquake at Jesus’s death.

This strictly functional purpose is merely the raison d’être for the Passion. Beyond it lie Bach’s own intentions for fulfilling his obligations while serving as cantor in Leipzig. Much of the following discussion owes a large debt to the rich treasure of information especially in John Eliot Gardiner’s Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, 2013 (Paperback - Illustrated, March 3, 2015) and also to Michael Marissen, Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism, and Bach’s St. John Passion, 1998; Eric T. Chafe, “The St. John Passion: theology and musical structure”, in Bach Studies, ed. Don. O. Franklin, 1989; and Robin A. Leaver’s “The mature vocal works…”, already cited. Interested readers are urged to see the far greater details in those works.

Bach’s First Year in Leipzig

In the first half of the 18th century, Leipzig was a staunchly Lutheran city governed by a council which acted not only in civic matters but also in ecclesiastical areas. It was they who oversaw the religious life and health of the churches and thereby the town. It was they, primarily, along with clergy, whom Bach had to satisfy when he applied for the position of Cantor at St. Thomas Church. In spite of a lively culture outside the churches, Leipzig was essentially a civic theocracy. The council, in its conservative wisdom, wanted music for their churches that was distinctly free of operatic or theatrical flavor, and were at pains to select just the right person to succeed the esteemed Johann Kuhnau as Cantor at St. Thomas School. Of course they wanted someone who would see to the music of the church and city; but they also wanted a schoolteacher who would instruct the St. Thomas students in Latin grammar and catechism (Bach bargained these away) as well as music skills. Five other candidates had declined the position before the council settled on someone who lacked renown and the credentials to teach in the church school, thus someone they considered “mediocre”—Bach.

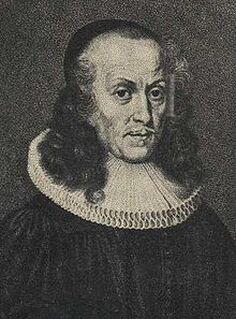

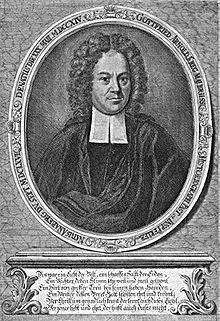

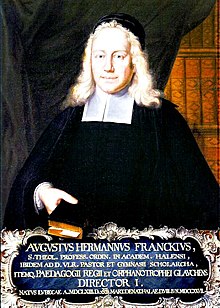

Although there were divisions within the council based on political affiliations of its members (the court vs. landed gentry—see Gardiner, 18-20), these powerful individuals were all of the Orthodox Lutheran persuasion which adhered to traditional services such as the Mass and formal theological models established in Martin Luther’s reform. Rigid and dogmatic Orthodox Lutheranism was countered at the end of the 17th century by a movement called Pietism, begun by Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705), Gottfried Arnold (1666-1714), and August Hermann Francke (1663-1727). At the root of the movement was a profound concern with a more intimate and emotional form Christianity that was captured in Count Nikolaus Zinzendorf’s phrase “the religion of the heart”. Akin to the “born again” Christianity of the 20th century, Pietism espoused a personalized relation to Jesus, a rebirth of the spirit leading to sincerity and fervor, and thus freedom from external dogmatic or practical formula and ceremony of Orthodoxy. By the time Bach was working in Leipzig, Pietists had produced a substantial body of sacred poetry, sermons, and meditative writings, some of which had far-reaching and long-term influence. Leipzig’s councilors were by default antagonistic toward Pietism, yet as we shall see, Bach’s work was impacted by the movement.

When Bach officially started his cantorial duties in Leipzig in May, 1723, he undertook not one job but at least three. What he considered the crux of his work was composing, preparing, and directing the music for the churches in the city. Although he was primarily stationed at one of two main churches in the city, St. Thomas, he also directed the music at it and the other principal church, St. Nicholas, and was responsible for providing music as well at St. George, St. Paul, and the New Church. Principal worship services were conducted on Sundays alternately at St. Nicholas and St. Thomas. Besides his obligations to the churches, Bach was to oversee and direct the music for all the city’s public events. Concomitant with these, he was to give musical training (vocal and instrumental) to 50 to 60 boys, generally aged 12 to 23, boarding at the St. Thomas School associated with St. Thomas Church, for they were to provide the music for the churches’ services. After some negotiation with a colleague, he was able to unburden himself of the task of teaching non-music courses at the school. However, he was responsible for maintaining order and discipline at the school and its dormitory (which was in the same building with, and immediately next to, his family’s quarters). Added to these duties were the problems of the decreasing musical preparation of the entering students, and the ongoing political wrangling within the council that spilled over into the council’s expectations of Bach’s music and his performance of his duties. These latter issues would seem to impinge most severely on Bach’s work, for he was composing music that was far more complex and demanding than that of his predecessor, Kuhnau, who had held the cantorial position at St. Thomas for the previous 22 years.

Amid the constant tumult of his daily obligations, Bach embarked on a plan to write cycles of sacred cantatas for every Sunday and feast day of the church year that would culminate in a Passion setting. Three such complete cycles exist, and portions of a fourth and fifth are extant. Fortunately, he had some earlier works up his sleeve to form the basis of the earliest weeks’ cantatas during his first year in Leipzig, during which he also produced 40 new cantatas. But there is no doubt that his plan was more than ambitious, not only in the demand on himself to keep composing the music on time, but perhaps even more in the almost shocking burden he placed on his singers and instrumentalists to learn—and perform acceptably—new and ever more challenging works each week. And beyond these pressures was the obligation to satisfy the city council, his employers, that his music for the Leipzig churches was suitably lacking in operatic theatricality, even as it was to convey concepts in keeping with Orthodox Lutheranism.

By the end of his first liturgical year, Bach had given his parishioners and his employers a degree of preparation for his first Passion setting, from the account in the gospel according to St. John. The work’s colorful instrumentation, antiquated and exotic by today’s standards, was unique even in that first Leipzig year. Although the oboes da caccia and d’amore had been present in various cantatas, they were only used singly, and not together in the same work, and the viola d’amore and lute had not appeared at all until in the St. John Passion. But more noteworthy would have been the music and non-Biblical content of the work. In the music the city councilors faced an unprecedented degree of complexity, dissonance, chromaticism, rhythmic energy, and even pictorialism, bordering dangerously on their concept of the unwanted “operatic” style. Even more, some of the new-created text smacked of sentimentality and graphic vividness, leaking into Orthodox objectivity from sources such as the then-famous garish poetic meditation on the Passion by Barthold Heinrich Brockes (1680-1747).

This then-famous poetic version of Jesus’s passion had previously been set to music by Reinhold Keiser, Telemann, Handel, Johann Mattheson, Gotfried Heinrich Stölzel, and Johann Friedrich Fasch. Brockes’s Passion was notoriously maudlin in its sentimentality and dwelt on the gruesome features of Jesus’s wounds in order to arouse in the reader/hearer a strong emotional response. Pulling as it did on the heartstrings, it was decidedly linked with Pietism, the polar opposite of the Orthodox orientation of the councilors. One aria which Bach included in this first Passion was indeed a rewrite of a portion of Brockes’s Passion with a few words changed to suit John’s point of view; another was clearly derived from Brockes (Marissen, 28-29). Even more, as Gardiner points out (p. 360-61), Part I of Bach’s St. John Passion is built on the scheme of Pietist theologian August Hermann Francke’s commentary on John’s gospel account, even to the point of similar meditative themes occurring in corresponding places in the narrative. Truth be told, it is difficult to find a Bach cantata that does not contain poetry smacking of a Pietistic bent, but the poetry in the St. John Passion appears to have run exceedingly close to the Pietistic Lutheran edge in arias and ariosos while still presenting the “straight” Orthodox biblical narrative. The odor of Pietism in this Passion’s non-scriptural poetry and the vivid, unremitting urgency and immediacy of the music must have sent shock waves through both council and congregation in 1724.

Bach used every tool at his disposal to bring the gospel text to life and to illuminate John’s message. Some of these tools are not readily audible to a general audience. For instance, scholars, including Gardiner, have described an inverted arch structure over the course of the work as Jesus’s degradation deepens and then he is lifted up and glorified in the crucifixion. Eric Chafe further shows that Bach carefully constructed his key centers in a system of symmetrical patterns, and that the key signatures have symbolic meaning.

The system of keys works within the Passion in alignment with the events taking place. For most of us, all of these symbols are “Augenmusik”—music for the eyes. However, what is audible is rhetoric, the art of moving the audience, which was fundamental to Baroque composers’ style ever since the time of Monteverdi. Bach’s success with it was one reason that he is considered a preacher through his music, as may be made clear in the following discussion.

St. John Passion

Part I

The very first chorus of the St. John Passion gives a good idea of the impact that the work may have had on the congregation at that first performance. The first sounds in the introduction capture the ear immediately: above the strings’ swirling, driving rhythm and insistent repeated note in the bass, pairs of oboes and flutes writhe and climb, forming and resolving suspensions in an ever-expanding chain of chromatic harmonies, suggesting the torment of the coming events (the literal passion or suffering of Jesus). Then the chorus sings three firm chords--Lord, Lord, Lord—on strong beats separated by rests, going forward on the word Ruler in an explosion of swirling, rising activity mimicking the orchestra. Then three more chords on alternate weak beats change the balance of the motion. Next a section of imitative entries, Show us, suggestive of a fugue with the tersest and most jagged of subjects characterized by octave leaps. The voice parts expand to wide-ranging, crossing melodic lines opposed by more of the chordal exclamations. Bach went to great lengths to present highly contrasting musical ideas that suggest the theological dichotomy between Jesus’s presence in the world and his elevation on the cross, his abasement and his glorification. Imbedded in the themes are lots of hidden but audible symbolic details, including crossing melodies (Bach’s specialty for referring to the cross) and long drawn-out rising motifs (in keeping with the gospel’s notion that Jesus’s crucifixion “draws” believers to him through his being raised on the cross). There is no chorale in this opening chorus, nothing to relieve or calm the senses of the listeners. Its da capo form was an operatic convention. Its fire and brimstone harshness defied all conventions of polite piety.

After this highly charged opening chorus, the narrative tells Jesus’s experience in the garden with his disciples, and Bach draws characters in his music right away. The soldiers of the High Priest come to arrest him, and Jesus asks who they are looking for. Their answer, “Jesus of Nazareth”, set boldly high in the voices, is accompanied by active bustling in the bright, high instruments—two flutes and first violins. Jesus responds “Ich bins” (I Am [he]). These German words have a special connotation: they are Luther’s translation of the phrase God used to tell his name to Moses, and here Jesus’s words identify him as God! This becomes the basis for the religious authorities to seek Jesus’s death, and it is the foundation of John’s gospel message being presented to Bach’s congregation. Hearing these words, the soldiers recoil and fall to the ground. When they recover themselves enough to ask again for Jesus of Nazareth, Bach reshapes their chorus to be less certain: instrumental and vocal pitches are lower, the high flutes no longer participate, and the flashy activity in the instruments is reduced to only the first violin part. Jesus’s statement “Ich bins” will later be brought to mind when Peter denies being one of Jesus’s disciples by saying “Ich bins nicht”—I am not!

Bach's St. John Passion - Herr, unser Herrscher (chorus)

Bach's St. John Passion, BWV 245

Netherlands Bach Society, Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

Bach's St. John Passion, BWV 245

Netherlands Bach Society, Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

As the Passion story unfolds, the listener is treated to increasing degrees of intensity. Consider two arias relating to Peter’s actions late in Part I. At first he is eager to defend Jesus from the crowd that ultimately takes him captive, and to follow him into his interrogation by Annas and then Caiaphas, the High Priest. The aria “Ich folge dir” (I follow you) for soprano with flute accompaniment, reflects Peter’s eagerness with “running” scales at a bright pace, in a major key, and with a cheerful dance-like rhythm in triple meter.

Bach's St. John Passion - Ich folge dir gleichfalls (soprano aria)

Sunhae Im - soprano

Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin René Jacobs

Sunhae Im - soprano

Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin René Jacobs

But once Peter is actually at the gate of Caiaphas’s court and is challenged by those who saw him with Jesus, Peter caves in and three times denies he is one of Jesus’s followers (Ich bins nicht!). The aria (“Ach, mein Sinn”) following Peter’s third denial is also in triple meter, and is also dance-like, but of a very different nature. Its dotted rhythms, cherished by composers for the French aristocracy at the time, are set in the slower pattern of a sarabande, and the falling chromatic bass line of remorse is countered by successively rising short bass patterns separated by gaps—rests—vividly suggesting greater and greater distress as the aria progresses. Unpredictable leaps and changes of direction in the vocal melody attest to Peter’s great distraction—a very different portrait of his condition from that in the previous aria.

Bach's St. John Passion - Ach, mean Sinn (tenor aria) with original score

Neill Archer - tenor

The Monteverdi Choir

The English Baroque Soloists

Conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

Neill Archer - tenor

The Monteverdi Choir

The English Baroque Soloists

Conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

St. John Passion

Part II

Part II of the Passion becomes even more dramatic and decidedly symbolic in structure. The central focus is Jesus’s trial before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. Bach took special care with this passage. German theologian and Bach scholar Friedrich Smend (1893-1980) revealed that Bach had constructed a large chiasm (cross form) for the series of events beginning with the chorus of religious authorities’ “Not this man, but Barabbas!” and ending with their chorus “Do not write ‘King of the Jews’”; text groups are clustered within to form symmetrical patterns (Leaver, 102). At the center of this large cross is a choral piece, “Through your captivity, Son of God” (set like a chorale but re-created from an aria), celebrating the paradox of Jesus’s imprisonment and the liberation of the believer (Marissen, 58).

In this dramatic trial we meet not only Pilate, representing the civil authority of Rome, but also the religious authorities, who are determined to get rid of Jesus because they see him as a blasphemer in identifying himself with the divine name (Ich bins) and claiming to be the king of Israel. Both of these forces have roles as antagonists in the story, but they are strongly contrasted against each other in Bach’s music. Pilate and Jesus have a conversation about Jesus’s identity and his status in the Jewish community. Their exchanges are conducted calmly in recitative. Pilate, having to deal with a Jewish prisoner with no apparent criminal charge, tries to find out who Jesus is, and asks if he is a king. When Jesus responds that his kingdom is “not of this world”, and that he is in the world to “bear witness to the truth”, all Pilate does is ask, “What is truth?” Pilate is convinced that Jesus is not a criminal and wants to release him, but he is continually blocked by the religious authorities who are upholding their laws.

These religious authorities are another matter. Bach portrays them as a malicious, angry mob. Unlike the two earlier crowds of Jews in Part I (soldiers in the garden capturing Jesus, and chattering servants outside Caiaphas’s court), these high-ranking religious figures achieve a shocking, unremittingly strident ugliness in their several choruses as they insist that Pilate take responsibility for judging Jesus. Bach casts their determined pressuring in a high range for sopranos, who sit predominantly at the top of the treble staff and rise several times to high A. They call for Pilate to free a condemned murderer instead of Jesus and in two long, contrapuntal choruses (22 and 26 measures, respectively) urge Jesus’s crucifixion. In contrast to their pious refusal to defile themselves by stepping into the Roman court precincts, their avowal of allegiance to Caesar reveals them as collaborators with the Romans. Ultimately they goad Pilate into condemning Jesus by extortion: since Jesus claims to be king, they say, he “speaks against Caesar”; if Pilate releases Jesus, he is no friend of Caesar.

Bach’s portrayal of Jesus’s humiliation is vivid, beyond most listeners’ expectations of Bach’s music. The religious authorities vilify Jesus with pressing rhythms, tangled counterpoint, rising pitch ranges. Pilate scourges him in one of the most vicious passages of recitative ever composed. Roman soldiers cynically adorn him with vestments of royalty—a crown of thorns and robe of royal purple—then beat him and mock him: “Hail, King of the Jews!” The final abasement, and yet paradoxically Jesus’s glorification, is the crucifixion, a Roman execution urged by the religious authorities. Pilate even places on the cross an inscription: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”. Yet through all this, and especially the crucifixion, John’s text makes clear that everything said about Jesus by his abusers in cynical mockery is the truth: he is the Son of God, he is King of the Jews.

Following instances of torture and humiliation, Bach counters with moments of reflection. Some of these are chorales as communal expressions of repentance, or prayers for forgiveness, or thoughts of hope and praise. Others are intimate solos, often containing memorable imagery and rhetoric in their poetry. Right after Pilate has so harshly scourged Jesus, the soul ponders consequences of Jesus’s pain from a crown of thorns and the ironic sweetness of the flowers—key-of-heaven—that bloom from their branches. The soul’s affective, delicate bass arioso (“Betrachte, meine Seel”), similar to a passage in Brockes’s Passion poem, has an unusual accompaniment of two muted solo violas d’amore and a lute as continuo instrument. Following this bass arioso, a tenor aria (“Erwäge”) considers how like the sky after a rainstorm Jesus’s battered back is, how like a rainbow, the sign of God’s grace. Of course Bach writes in rainbow-like arches in the tenor’s melody and in the accompaniment, which is given to two muted violas d’amore and cello (or viola da gamba) soloists.

All the torments of the trial lead to the crucifixion. In another aria derived from Brockes’s Passion, a bass soloist even urges a trio of troubled souls to rush to the crucifixion site at Golgotha. Even during the crucifixion the drama continues as the religious authorities try to have Pilate amend his written notice naming Jesus “King of the Jews” (he declines), soldiers gamble for Jesus’s robe, and Jesus commits care of his mother to his beloved disciple. In response to Jesus’s final statement on the cross, “It is completed” (“Es ist vollbracht”), Bach composed a heartrending aria for alto beginning with those words; the accompaniment is for two (unmuted) violas d’amore and viola da gamba, and Bach included the tempo specification “Molto Adagio”. But in the midst of this beautiful mournful aria, quite without transition or warning, the alto rings out a “vivace” victorious cry: “The hero from Judah conquers with strength and ends the battle!” and the stronger strings—two violin parts, viola, and cello—join the quiet solo instruments in excited fanfares. This brief window of glory, presaging Easter, hits at the core of John’s gospel, which had been projected in the powerful opening chorus. But the first idea returns, perhaps now with a coloring of accomplishment along with grief. What Bach has done through music is underline the contrast of the abuse and the glorification and victory over death that Jesus achieved on the cross, completing the work of redemption he was sent to do on earth. (A fine explanation of this theology may be found in Marissen, especially p. 18.)

After Jesus expires on the cross, a dance-like bass aria in a major key is interwoven with a chorale sung by the chorus. Perhaps reflecting on the fact that the gospel writer has put the blame for Jesus’s death on all parties--Jewish religious authorities, Romans, and, yes, the current believer—the soloist asks, “Have I been made free from death?...Is redemption of all the world here?...You exclaim in silence, ‘Yes’.” The chorus—that is, the community—reflects simultaneously on the redeeming death of Jesus, to whom they turn for eternal life. All of nature shudders, and the Temple veil is torn, graves open and bodies of the Saints arise. In response, a soprano sings one of Bach’s most plangent arias, “Dissolve, my heart, in floods of tears”, accompanied by a flute and oboe da caccia duet. Finally, Jesus’s body is laid to rest in the tomb, and the final monumental chorus contemplates the peace that believers have because heaven in now open to them. A simple concluding chorale is a prayer for the peaceful rest of both Jesus and the believer, and the believer’s joyful awakening to see Jesus and to praise him forever.

Bach"s St. John Passion - Ach Herr, laß dein lieb Engelein

Staats (und Domchor), Berlin RIAS Kammerchor

Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin René Jacobs

Staats (und Domchor), Berlin RIAS Kammerchor

Akademie für Alte Musik, Berlin René Jacobs

St. John Passion

After Word

Despite—or because of?—the power of his 1724 St. John Passion, Bach appears to have felt it wise to temper its style and content. In the following year he presented a revised version, changing the opening chorus to a grand arrangement of the chorale “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross” (Oh human, bewail your great sin), which he would use two years later in the opening chorus of his St. Matthew Passion. He replaced several key arias and chorales and changed the final movement to an extended treatment of the chorale “Christe, du Lamm Gottes” (Christ, you Lamb of God). The emphasis now was on Jesus as sacrificial victim rather than victor over death. In his last year, Bach returned to the original version.

Bach’s next major passion setting, in 1727, was of St. Matthew’s gospel. Probably the better known of the two today, this work is on a much grander scale than that of the St. John Passion, requiring two complete choirs and a children’s choir, two sets of soloists (except for the Evangelist), and two orchestras and continuos. In general, its tone is more contemplative than that of the St. John setting; there are more arias, and they are typically of the da capo type, which lengthens the performing time of the work. Chorales play a more structural role in the St. Matthew Passion, especially around the narrative of the crucifixion. And one important detail is added: Jesus’s text wears a “halo” of strings except in his cry of dereliction, “My God, why have you forsaken me?”

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Bach's St. John Passion, BWV 245

Netherlands Bach Society, Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

Raphael Höhn, evangelist, (tenor) | Myriam Arbouz, Soprano | Maria Valdmaa (Maid), soprano | Daniël Elgersma, alto | Marine Fribourg, alto | Gwilym Bowen, tenor | Guy Cutting (Servant), tenor | Felix Schwandtke (Jesus), bass | Drew Santini (Peter), bass | Angus Mc Phee (Pilate), bass

Netherlands Bach Society, Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

Raphael Höhn, evangelist, (tenor) | Myriam Arbouz, Soprano | Maria Valdmaa (Maid), soprano | Daniël Elgersma, alto | Marine Fribourg, alto | Gwilym Bowen, tenor | Guy Cutting (Servant), tenor | Felix Schwandtke (Jesus), bass | Drew Santini (Peter), bass | Angus Mc Phee (Pilate), bass

Time Stamps:

Akt 1: Verrat und Gefangennahme

0:00:17 Chorus Herr unser Herrscher

0:10:33 Rezitativ+Chorus Jesus ging mit seinen Jüngern

0:13:03 Choral O große Lieb

0:14:05 Rezitativ Auf daß das Wort erfüllet würde

0:15:16 Choral Dein Will gescheh

0:00:17 Chorus Herr unser Herrscher

0:10:33 Rezitativ+Chorus Jesus ging mit seinen Jüngern

0:13:03 Choral O große Lieb

0:14:05 Rezitativ Auf daß das Wort erfüllet würde

0:15:16 Choral Dein Will gescheh

Akt 2: Verleumdung

0:16:23 Rezitativ Die Schar aber und der Oberhauptmann

0:17:06 Arie Von den Stricken meiner Sünden

0:21:40 Rezitativ Simon Petrus aber folgete Jesu nach

0:21:56 Arie Ich folge dir gleichfalls

0:25:24 Rezitativ Derselbige Jünger war dem Hohenpriester bekannt

0:28:31 Choral Wer hat dich so geschlagen

0:30:37 Rezitativ+Chorus Und Hannas sandte ihn gebunden

0:32:53 Arie Ach, mein Sinn

0:36:05 Choral Petrus, der nicht denkt zurück

0:16:23 Rezitativ Die Schar aber und der Oberhauptmann

0:17:06 Arie Von den Stricken meiner Sünden

0:21:40 Rezitativ Simon Petrus aber folgete Jesu nach

0:21:56 Arie Ich folge dir gleichfalls

0:25:24 Rezitativ Derselbige Jünger war dem Hohenpriester bekannt

0:28:31 Choral Wer hat dich so geschlagen

0:30:37 Rezitativ+Chorus Und Hannas sandte ihn gebunden

0:32:53 Arie Ach, mein Sinn

0:36:05 Choral Petrus, der nicht denkt zurück

Akt 3: Verhör und Geißelung

0:37:40 Choral Christus, der uns selig macht

0:38:55 Rezitativ Da führeten sie Jesum

0:39:31 Chorus Wäre dieser nicht ein Übeltäter

0:40:30 Rezitativ Da sprach Pilatus zu ihnen

0:40:42 Chorus Wir dürfen niemand töten

0:41:18 Rezitativ Auf daß erfüllet würde das Wort

0:43:00 Choral Ach großer König

0:44:47 Rezitativ Da sprach Pilatus zu ihm

0:46:12 Chorus Nicht diesen, sondern Barrabam

0:46:22 Rezitativ Barrabas aber war ein Mörder

0:46:55 Arioso Betrachte, meine Seel

0:49:23 Arie Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken

0:56:07 Rezitativ Und die Kriegskneckte flochten eine Krone

0:56:24 Chorus Sei gegrüßet, lieber Judenkönig

0:56:57 Rezitativ Und gaben ihm Backenstreiche

0:57:50 Chorus Kreuzige, kreuzige

0:58:41 Rezitativ Pilatus sprach zu ihnen

0:58:59 Chorus Wir haben ein Gesetz

1:00:10 Rezitativ Da Pilatus das Wort hörete

1:01:36 Choral Durch dein Gefängnis, Gottes Sohn

1:02:46 Rezitativ Die Jüden aber schrieen und sprachen

1:02:50 Chorus Lässest du diesen los

1:03:57 Rezitativ Da Pilatus das Wort hörete

1:04:35 Chorus Weg, weg mit dem

1:05:31 Rezitativ Spricht Pilatus zu ihnen

1:05:42 Chorus Wir haben keinen König

1:05:54 Rezitativ Da überantwortete er ihn

1:06:46 Arie Eilt, ihr angefochtnen Seelen

0:37:40 Choral Christus, der uns selig macht

0:38:55 Rezitativ Da führeten sie Jesum

0:39:31 Chorus Wäre dieser nicht ein Übeltäter

0:40:30 Rezitativ Da sprach Pilatus zu ihnen

0:40:42 Chorus Wir dürfen niemand töten

0:41:18 Rezitativ Auf daß erfüllet würde das Wort

0:43:00 Choral Ach großer König

0:44:47 Rezitativ Da sprach Pilatus zu ihm

0:46:12 Chorus Nicht diesen, sondern Barrabam

0:46:22 Rezitativ Barrabas aber war ein Mörder

0:46:55 Arioso Betrachte, meine Seel

0:49:23 Arie Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken

0:56:07 Rezitativ Und die Kriegskneckte flochten eine Krone

0:56:24 Chorus Sei gegrüßet, lieber Judenkönig

0:56:57 Rezitativ Und gaben ihm Backenstreiche

0:57:50 Chorus Kreuzige, kreuzige

0:58:41 Rezitativ Pilatus sprach zu ihnen

0:58:59 Chorus Wir haben ein Gesetz

1:00:10 Rezitativ Da Pilatus das Wort hörete

1:01:36 Choral Durch dein Gefängnis, Gottes Sohn

1:02:46 Rezitativ Die Jüden aber schrieen und sprachen

1:02:50 Chorus Lässest du diesen los

1:03:57 Rezitativ Da Pilatus das Wort hörete

1:04:35 Chorus Weg, weg mit dem

1:05:31 Rezitativ Spricht Pilatus zu ihnen

1:05:42 Chorus Wir haben keinen König

1:05:54 Rezitativ Da überantwortete er ihn

1:06:46 Arie Eilt, ihr angefochtnen Seelen

Akt 4: Kreuzigung und Tod

1:10:32 Rezitativ Allda kreuzigten sie ihn

1:11:46 Chorus Schreibe nicht: der Jüden König

1:12:20 Rezitativ Pilatus antwortet

1:12:39 Choral In meines Herzens Grunde

1:13:58 Rezitativ Die Kriegsknechte aber

1:14:32 Chorus Lasset uns den nicht zerteilen

1:15:54 Rezitativ Auf daß erfüllet würde die Schrift

1:17:46 Choral Er nahm alles wohl in acht

1:19:10 Rezitativ Und von Stund an nahm sie der Jünger

1:20:28 Arie Es ist vollbracht

1:25:55 Rezitativ Und neiget das Haupt

1:26:21 Arie Mein teurer Heiland, laß dich fragen

1:30:35 Rezitativ Und siehe da, der Vorhang im Tempel zerriss

1:31:03 Arioso Mein Herz, in dem die ganze Welt

1:32:01 Arie Zerfließe, mein Herze

1:38:35 Rezitativ Die Jüden aber, dieweil es der Rüsttag war

1:40:43 Choral O hilf, Christe, Gottes Sohn

1:10:32 Rezitativ Allda kreuzigten sie ihn

1:11:46 Chorus Schreibe nicht: der Jüden König

1:12:20 Rezitativ Pilatus antwortet

1:12:39 Choral In meines Herzens Grunde

1:13:58 Rezitativ Die Kriegsknechte aber

1:14:32 Chorus Lasset uns den nicht zerteilen

1:15:54 Rezitativ Auf daß erfüllet würde die Schrift

1:17:46 Choral Er nahm alles wohl in acht

1:19:10 Rezitativ Und von Stund an nahm sie der Jünger

1:20:28 Arie Es ist vollbracht

1:25:55 Rezitativ Und neiget das Haupt

1:26:21 Arie Mein teurer Heiland, laß dich fragen

1:30:35 Rezitativ Und siehe da, der Vorhang im Tempel zerriss

1:31:03 Arioso Mein Herz, in dem die ganze Welt

1:32:01 Arie Zerfließe, mein Herze

1:38:35 Rezitativ Die Jüden aber, dieweil es der Rüsttag war

1:40:43 Choral O hilf, Christe, Gottes Sohn

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.