- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

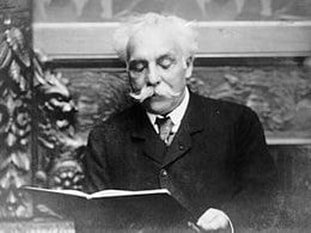

Gabriel Faure's

Requiem, D minor, Op. 48

Good Friday Concert Program Notes

March 25, 2016

REQUIEM

([] = omissions and changes from the Requiem Mass liturgy)

I. Introit and Kyrie

Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and may light perpetual shine on them. A hymn befits the, O God in Zion, and to thee a vow shall be fulfilled in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer; to thee all flesh shall come. Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy.

[Sequence: Dies irae]

II. Offertory

O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, free the souls of [all the faithful] the departed [from the pains of hell and from the deep pit, deliver them] from the mouth of the lion, do not let hell swallow them. O lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, do not let them fall into darkness [but let Michael the holy standard-bearer bring them into the holy light, which once thou promised to Abraham and to his seed]. We offer sacrifices and prayers of praise to thee, Lord; do thou receive them on behalf of the souls of those souls we commemorate today. Grant them, Lord, to pass from death to life, which once you promised to Abraham and his seed. [O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, free the souls of [all the faithful] the departed from pains of hell and from the deep pit; do not let them fall into darkness. Amen.]

III. Sanctus

Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory. Hosanna in the highest. [Holy.]

IV. Pie Jesu [final lines of Sequence “Dies irae”]

Merciful Jesus Lord, grant them rest, [everlasting rest].

V. Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, grant them rest. (Repeated.) Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, grant them everlasting rest. (Communion) May eternal light shine on them, Lord, with thy saints for eternity, for thou art merciful. Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and let light perpetual shine on them.

VI. Libera me [Responsory from the Burial Rite]

Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death on that momentous day, when heaven and earth are shaken, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Trembling am I, and terrified until the coming of judgment and wrath: that day, the day of wrath, calamity and misery, the momentous and exceedingly bitter day, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them. [Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death on that momentous day, when heaven and earth are shaken, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Deliver me, Lord.]

VII. In Paradisum [After the Mass and Burial Rite]

May angels lead you into paradise; may martyrs welcome you at your arrival and lead you into the holy city Jerusalem. May a choir of angels welcome you, and, with Lazarus, once poor, may you have eternal rest.

([] = omissions and changes from the Requiem Mass liturgy)

I. Introit and Kyrie

Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and may light perpetual shine on them. A hymn befits the, O God in Zion, and to thee a vow shall be fulfilled in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer; to thee all flesh shall come. Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy.

[Sequence: Dies irae]

II. Offertory

O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, free the souls of [all the faithful] the departed [from the pains of hell and from the deep pit, deliver them] from the mouth of the lion, do not let hell swallow them. O lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, do not let them fall into darkness [but let Michael the holy standard-bearer bring them into the holy light, which once thou promised to Abraham and to his seed]. We offer sacrifices and prayers of praise to thee, Lord; do thou receive them on behalf of the souls of those souls we commemorate today. Grant them, Lord, to pass from death to life, which once you promised to Abraham and his seed. [O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, free the souls of [all the faithful] the departed from pains of hell and from the deep pit; do not let them fall into darkness. Amen.]

III. Sanctus

Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory. Hosanna in the highest. [Holy.]

IV. Pie Jesu [final lines of Sequence “Dies irae”]

Merciful Jesus Lord, grant them rest, [everlasting rest].

V. Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, grant them rest. (Repeated.) Lamb of God, who bears the sins of the world, grant them everlasting rest. (Communion) May eternal light shine on them, Lord, with thy saints for eternity, for thou art merciful. Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and let light perpetual shine on them.

VI. Libera me [Responsory from the Burial Rite]

Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death on that momentous day, when heaven and earth are shaken, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Trembling am I, and terrified until the coming of judgment and wrath: that day, the day of wrath, calamity and misery, the momentous and exceedingly bitter day, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them. [Deliver me, Lord, from eternal death on that momentous day, when heaven and earth are shaken, when thou shalt come to judge the world by fire. Deliver me, Lord.]

VII. In Paradisum [After the Mass and Burial Rite]

May angels lead you into paradise; may martyrs welcome you at your arrival and lead you into the holy city Jerusalem. May a choir of angels welcome you, and, with Lazarus, once poor, may you have eternal rest.

The Monteverdi Choir conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

Although brought up and educated in religious environments, Fauré was in his adulthood not a practitioner of his faith. When deciding to set the text of the liturgical Requiem Mass he said it was “for pleasure”, even though both of his parents had died within the previous two years. His philosophy, which in letters he expressed as “’God’ is the synonym for ‘Love’”, may well have guided these choices. But Fauré’s biographer, Jean-Michel Nectoux, suggests that there was a musical reason for the omissions: Fauré may have wanted to step away from the path established by Berlioz and Verdi in their monumental Requiems and create “something different”, and he was also deviating from the earlier models of Mozart and Michael Haydn. He omitted significant portions of the liturgy, notably the long Dies irae poem, describing judgment day and the horrors of eternal damnation, and the Benedictus; further, he abbreviated several sections of text, changed the order of some texts, and introduced texts from other portions of liturgy. What appears in Fauré’s Requiem is the “something different” that he aspired to: a kinder and gentler view of the Church’s liturgy about death. His work is a paradigm for the atmosphere of Duruflé’s work that would come nearly 50 years later, but unlike Duruflé, Fauré composed his setting without utilizing specific liturgical chants.

It took roughly 20 years for Fauré’s Requiem to realize publication. He began in 1887 with sketches for part of the Introit and the baritone solo in the Hostias. By the end of January 1888 five movements were completed: Introit and Kyrie, Sanctus, Pie Jesu, Agnus Dei, and In Paradisum. The unusual orchestration of this first version consisted of a solo violin (in the Sanctus), divided violas and cellos, basses, harp, timpani, and organ; Fauré conducted a performance of what he called his “petit Requiem” in January 1888 for a funeral at the Madeleine (because women were not permitted to sing there, a boy soloist sang the Pie Jesu). He added one trumpet and one horn for a performance he conducted in May of that year, again at the Madeleine; somewhat later two each of trumpets and horns as well as bassoons appeared in the manuscript. By 1890 he had added the Offertory and Libera me, essentially completing the Requiem; the work with this orchestration was premiered in 1893 at the Madeleine with Fauré conducting. In its original form, the Requiem’s style and tone clearly represented Fauré’s unassuming nature and his aesthetic of gentleness and intimacy, as Nectoux pointed out.

However, in the following ten years Fauré’s publisher, thinking to offer a work more attractive to the public, worked with Fauré’s friend Léon Boëllmann and later his pupil Roger-Ducasse to create a piano/vocal score and to expand the orchestration beyond that of the 1890 version of the Requiem. This late version included two flutes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, two harps, and full strings, and organ, undergirding basically unchanged choral and solo parts. The vocal score appeared in 1900, and the full orchestral version in 1901, both with Fauré’s approval.

In the first version of his Requiem Fauré may have been following Brahms’s plan over a decade earlier in the German Requiem. Not only did he eliminate the violins from most of the work, but he also organized his work around the central Pie Jesu movement (for solo soprano) and formed a clear symmetry on either side: baritone solos in movements two and six; a return of the opening “Requiem aeternam” theme in movement five (Agnus Dei); similar “celestial” effects of chorus and accompaniment in movements three (Sanctus) and seven (In Paradisum); and other numerous instances. Unique moments also abound: the ambivalent tonality at the opening of the Offertory, set as a quasi canon; the sudden shift in harmonic character in the midst of the Agnus Dei, not only in key orientation but in extraordinary chromatic movement and unexpected key shifts created by renaming pitches (enharmonic changes); the antiphonal exchanges of “Sanctus”; and the stunning “Hosanna!” cries, approaching and receding as if in procession, in the third movement. The only reference to impending doom of a judgment day comes in the sixth movement, Libera me, when Fauré sets the remnant of the “Dies irae” poem, as prescribed in the liturgy. Far from conforming to the popularized stereotype of Fauré’s music as mild and delicate, this moment bursts forth with stunning ferocity, the vestigial dark side of his vision of the liturgy of death—which nevertheless he considered a “joyful deliverance…rather than a painful experience”.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) spent his first eight years in the environs of Foix, south of Toulouse. His father, Toussaint-Honoré, served as schoolmaster and then inspector of teacher-training in the region for many years. In the latter capacity he brought the family to Montgauzy, where in 1849 Gabriel entered boarding school. Approximate to the school was a chapel, a relic of an abandoned convent, and in the chapel was a harmonium—a simple reed organ which the performer supplied with air by pumping pedals. Young Fauré began his musical life by improvising on this instrument, and seems to have been given some basic instruction on piano at his school as well. He was sufficiently practiced that a visitor who heard him play advised Toussaint to send his son to a new school being opened by Louis Niedermeyer in Paris. Gabriel was accepted as a pupil at age 9 and remained there for 11 years.

The Niedermeyer School formed the foundation of Fauré’s career and compositional style. The curricular focus on sacred music and classical education in the humanities was distinctly different from that at the well-established Paris Conservatoire. More important, this was a period in which church music was at its nadir, having been almost wholly disregarded in the aftermath of the French Revolution and fallen under the sway of church officials and congregants with no musical training or regard for the rich heritage of church music. Niedermeyer’s school sought to remedy the effects of the uninformed taste of the clergy and to counteract the influence of popular theater music at the time: it aimed specifically at preparing church organists and choirmasters. Harmony, composition, sight-reading and choral singing, organ (and piano), and conducting all aided in the development of not only the practical work of choirmasters but also of pedagogy—educating younger students in musical skills. Niedermeyer also included studies in polyphony in the curriculum, at a time when the technique was well out of the consciousness of musical training in France. The students sang music of Renaissance composers Josquin, Palestrina, and Victoria as well as of J. S. Bach, not only as part of their studies but also in church services. These experiences appear to have fostered Fauré’s affinity with counterpoint, a technique in which he was particularly skilled, and informed his proclivity for writing long, unfolding melodies.

While at the school Fauré was heavily influenced not only by Niedermeyer himself but also by an older student, Camille Saint-Saëns, who was at first Fauré’s teacher and then his mentor and friend throughout the rest of his life. Through Saint-Saëns’s classes Fauré discovered then-avant-garde music of Schumann, Liszt, Wagner, and other composers outside Niedermeyer’s canon, and with Saint-Saëns’s encouragement Fauré began to compose. Fauré’s first works as a student were songs, yet early as they were, they display the abiding traits of fluid, beautifully formed melody and sometimes astonishing harmonies that mark all of his music. Among his earliest choral works, the “Cantique de Jean Racine” won first prize in composition in 1865, just at the end of his years at the Niedermeyer School.

After 1865, Fauré’s career took him into several church positions, interrupted for about eight months by his serving in the infantry during the Franco-Prussian War and briefly teaching composition in Switzerland. Returning to Paris in 1871 he served as second organist at St. Sulpice, where he accompanied the choir and engaged in improvisation “duels” with the primary organist, Charles-Marie Widor. Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré to musicians with whom he joined to form the Société Nationale de Musique, supporting the development of music by French composers. In 1874 he became Saint-Saëns’s substitute at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris. He would remain at the Madeleine through many years, first as assistant organist, then as choirmaster, then in 1896 as chief organist. His role as teacher through his years at the Madeleine expanded with his appointment in composition at the Paris Conservatoire, and in 1905 as its director; without question, his work as a composer, widely recognized by his middle and late years, appears to have been greatly compressed by his teaching obligations.

It may come as a surprise today that as a composer Fauré was considered a renegade, subtly but unquestionably working outside the conservative norms of accepted practice in his time. His extraordinary gift for writing smooth, even sensuous melodies set in rich harmonies rooted in tonality was countered by the boldness of unusual and even frequent key changes, and modal harmonies (derived from his studies of church music at the Niedermeyer School). Some aspects of the Impressionists, his contemporaries, also appear in his music, such as whole-tone scales and tonality-obscuring chromaticism. Besides his many songs and piano pieces, he composed several operatic works and incidental music for the stage, more than a dozen motets of various sizes, two versions of a mass Ordinary, a Requiem, and a number of orchestral and chamber works.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

The Niedermeyer School formed the foundation of Fauré’s career and compositional style. The curricular focus on sacred music and classical education in the humanities was distinctly different from that at the well-established Paris Conservatoire. More important, this was a period in which church music was at its nadir, having been almost wholly disregarded in the aftermath of the French Revolution and fallen under the sway of church officials and congregants with no musical training or regard for the rich heritage of church music. Niedermeyer’s school sought to remedy the effects of the uninformed taste of the clergy and to counteract the influence of popular theater music at the time: it aimed specifically at preparing church organists and choirmasters. Harmony, composition, sight-reading and choral singing, organ (and piano), and conducting all aided in the development of not only the practical work of choirmasters but also of pedagogy—educating younger students in musical skills. Niedermeyer also included studies in polyphony in the curriculum, at a time when the technique was well out of the consciousness of musical training in France. The students sang music of Renaissance composers Josquin, Palestrina, and Victoria as well as of J. S. Bach, not only as part of their studies but also in church services. These experiences appear to have fostered Fauré’s affinity with counterpoint, a technique in which he was particularly skilled, and informed his proclivity for writing long, unfolding melodies.

While at the school Fauré was heavily influenced not only by Niedermeyer himself but also by an older student, Camille Saint-Saëns, who was at first Fauré’s teacher and then his mentor and friend throughout the rest of his life. Through Saint-Saëns’s classes Fauré discovered then-avant-garde music of Schumann, Liszt, Wagner, and other composers outside Niedermeyer’s canon, and with Saint-Saëns’s encouragement Fauré began to compose. Fauré’s first works as a student were songs, yet early as they were, they display the abiding traits of fluid, beautifully formed melody and sometimes astonishing harmonies that mark all of his music. Among his earliest choral works, the “Cantique de Jean Racine” won first prize in composition in 1865, just at the end of his years at the Niedermeyer School.

After 1865, Fauré’s career took him into several church positions, interrupted for about eight months by his serving in the infantry during the Franco-Prussian War and briefly teaching composition in Switzerland. Returning to Paris in 1871 he served as second organist at St. Sulpice, where he accompanied the choir and engaged in improvisation “duels” with the primary organist, Charles-Marie Widor. Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré to musicians with whom he joined to form the Société Nationale de Musique, supporting the development of music by French composers. In 1874 he became Saint-Saëns’s substitute at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris. He would remain at the Madeleine through many years, first as assistant organist, then as choirmaster, then in 1896 as chief organist. His role as teacher through his years at the Madeleine expanded with his appointment in composition at the Paris Conservatoire, and in 1905 as its director; without question, his work as a composer, widely recognized by his middle and late years, appears to have been greatly compressed by his teaching obligations.

It may come as a surprise today that as a composer Fauré was considered a renegade, subtly but unquestionably working outside the conservative norms of accepted practice in his time. His extraordinary gift for writing smooth, even sensuous melodies set in rich harmonies rooted in tonality was countered by the boldness of unusual and even frequent key changes, and modal harmonies (derived from his studies of church music at the Niedermeyer School). Some aspects of the Impressionists, his contemporaries, also appear in his music, such as whole-tone scales and tonality-obscuring chromaticism. Besides his many songs and piano pieces, he composed several operatic works and incidental music for the stage, more than a dozen motets of various sizes, two versions of a mass Ordinary, a Requiem, and a number of orchestral and chamber works.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.