- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

PROGRAM NOTES: NOVEMBER 21, 2014

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) has been revered by listeners, churchgoers, and musicians of all stripes the world over for good reason: it is technically superb, artistically impeccable, symbolically rich, and emotionally satisfying, and performers find it among the most demanding music there is. This evening’s concert represents much of Bach’s long career with works of different genres, which reveal some elements that may surprise today’s audiences.

Bach was born in Eisenach, Germany, into a devout Lutheran family of strong musical bent (and he extended this musical tradition to his children). An exceptional keyboard performer, he also played violin, and was even in his teens an outstanding organist; in his maturity he was respected as perhaps the best organist at least in Germany if not the world. Of the five major positions he held, three were as a church musician (at Arnstadt, 1703-1706, Mülhausen, 1707-1708, and Leipzig), meaning that he served variously as a church organist, choir director, and composer. At Arnstadt the 18-year-old Bach also began a tangent of his career as an organ inspector, tester, and exhibitor—work for which he would be sought through the rest of his life. At Weimar, 1708-1717, he was primarily a music teacher to the duke’s nephew, a court organist, chamber musician, and also a church organist and composer. At Anhalt-Cöthen, 1717-1723, in the completely secular position of Kapellmeister, he composed primarily for the elector and his instrumentalists. But he also was raising a family there, so he created extended didactic works systematically laid out to train young students, including his own children. Bach’s works from the Cöthen years range through all instrumental genres (and a few songs) except for organ: suites; sonatas and concertos; collections of educational works such as the clavier books for his wife, Anna Magdalena, and his son Wilhelm Friedemann; two- and three-part keyboard inventions; and the preludes and fugues comprising Book I of the Well-Tempered Keyboard.

By far Bach’s longest employment was at Leipzig, from 1723 until his death. Leipzig was a bastion of Lutheranism, and the city government was a de facto voice of church policy. Here, as the town council’s sixth choice for what was essentially a civic job—Director of Music for the city—Bach was obliged to provide, direct, and supervise music in the city’s two major churches, alternating between Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche, and at civic events, as well as at festivals at the church at Leipzig University. His “day job” was as Kantor (third in seniority) at St. Thomas School, where he was responsible for teaching singing and music skills to the boys, preparing them to perform the music in church services, and generally assisting with supervising their daily activities. He was originally required to teach subjects other than music, such as Latin and mathematics, but he quickly found a replacement whom he paid to take over those classes. For a period he also served as director of the collegium musicum at Leipzig University. Not surprisingly, because he needed music every week for the city’s two important churches, he was continually composing sacred works. The great majority of his cantatas are from this period, as are the passions, the Christmas and Easter oratorios, the Mass in B minor, the motets, and again collections of pedagogical works such as a portion of the Clavier-Übung and the Art of Fugue.

Two vocal genres that Bach needed for the church were cantatas and motets. The cantata, involving a choir, soloists, and instrumental accompaniment, usually begins and ends with a chorale, or Lutheran hymn, with which the congregation would be very familiar and would join at the end of the work. The body of the cantata would alternate between chorale verses, new prose set as recitative, and poetry set as an aria; all were generated from the scripture for that day. Thus the cantata formed a kind of supplement to the pastor’s sermon. Bach wrote hundreds of sacred cantatas, famously cycles for four years in Leipzig. Some 200 (about 60%) of the total for his career are extant.

The motets, of which there are only six or seven (there is a debate over authenticity of one of them), are for choirs from four to eight voice parts, with texts either from scripture or newly written sacred poetry. Written for special occasions such as birthdays or funerals, most of them in some way include a chorale. Even though they are for an ensemble of voices, the motets are more technically advanced than the cantatas.

As will be evident in the following discussions related to “Bach by Candlelight”, Bach’s music varies greatly in its purpose, resources, attitude, and technical details.

As will be evident in the following discussions related to “Bach by Candlelight”, Bach’s music varies greatly in its purpose, resources, attitude, and technical details.

Concerto for Violin and Oboe, BWV 1060

While serving at the Weimar court (1708-1717), Bach gained access to the Italian concerto style when the duke acquired copies of Vivaldi’s music. Assimilating Vivaldi’s melodic clarity and rhythmic style, Bach fused them with his own contrapuntal ingenuity when writing his mature instrumental works. In addition to composing his own concertos in the Italian format, he also made transcriptions of them for from one to four harpsichords (and some for organ). The Concerto for Violin and Oboe on this program went through this kind of life cycle. Scholars believe it to have been written in Cöthen, but the only version of it exists in a transcription for two harpsichords from Bach’s Leipzig period (1723-1750). Because the melody lines are identifiably characteristic as violin and oboe lines, the transcription has been reversed into a concerto for those two solo instruments.

Bach used Vivaldi’s three-movement model for the concerto. The Allegro first movement features relatively equal soloists. The Adagio second movement, however, principally features the oboe, with violin supporting it and highlighted only in a short cadenza. The final movement, Allegro, provides plenty of idiomatic music for both instruments; the oboe generally provides the melody while the violin executes virtuosic decoration above.

Motet 6: Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden, BWV 230

The authenticity of “Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden” was for a long time questioned because of its stylistic features. Now, however, this motet is generally accepted as a work by Bach, although there is no known commission or occasion for it, and, uncharacteristically, there is no chorale within it. Unlike the other motets, its four choral voices are supported by obbligato organ, which Gerhard Homann, writing for the 1982 Bellaphon recording, explains as evidence the motet was intended the Leipzig University’s Pauline Church, the one church in the city that allowed instruments in funeral services. Bach set verses from Martin Luther’s translation of Psalm 117 in several sections, marked by changes in theme, texture, and tempo. The abundantly cheerful tone is established from the beginning by an unusually wide rising fugue subject on the word “lobet” (praise); on “preiset” (extol), a second fugue with a subject begins in downward direction. A quieter, more homophonic section affirms trust in God’s grace and guidance. The ebullient “allelujah”, a dance-like fugue, joyfully concludes the work.

Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden, und preiset ihn, alle Völker;

denn seine Gnaden und Wahrheit waltet über uns in Ewigkeit. Alleluia.

Praise the Lord, all nations, and extol him, all people;

for his mercy and truth rule over us forever. Alleluia.

denn seine Gnaden und Wahrheit waltet über uns in Ewigkeit. Alleluia.

Praise the Lord, all nations, and extol him, all people;

for his mercy and truth rule over us forever. Alleluia.

Cantata BWV 8: Liebster Gott, wann werd’ ich sterben?

Composed in 1724 for the 16th Sunday of the season of Trinity (from Pentecost to Advent), this cantata employs soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists and choir, accompanied by horn, flute, two oboes d’amore, strings, and continuo (keyboard and cello). The first and last movements are settings of two verses of Casper Neumann’s chorale; the intervening movements—two arias, each followed by a recitative—are on anonymous texts. What sets this cantata apart musically is the importance of the obbligato instruments—flute and oboe d’amore—and the seeming airiness of the accompaniment throughout all but the final choral.

On its surface, the cantata strikes one as being one of Bach’s least prepossessing. What? Only two arias? Only two choral movements? And a reversed order of recitative and aria? But we should remember that Bach never wrote without purpose. His music in this cantata effectively shows the glorious adornments being slowly reduced until the final chorale stands without trappings, purely in its essence.

On its surface, the cantata strikes one as being one of Bach’s least prepossessing. What? Only two arias? Only two choral movements? And a reversed order of recitative and aria? But we should remember that Bach never wrote without purpose. His music in this cantata effectively shows the glorious adornments being slowly reduced until the final chorale stands without trappings, purely in its essence.

The text of the opening movement speaks of the individual believer’s acknowledgement of his mortality. The extended setting of the first chorale verse is one of the most remarkable examples of Bach’s sweet, gracious vision of the soul’s longing for death. In effect, there are six sonic units at work here. A duet between the two oboes d’amore forms the melodic basis in the orchestra; above them is a rapid, insistent flute note, appearing and disappearing, keeping metronomic time. Beneath these, the bass line moves in sedate clock-like regularity, while the pizzicato strings provide lacy harmony within which the choir presents its phrases. Adding to the airiness of the texture, the choir’s sopranos begin the chorale tune briefly alone before continuing on in their graceful modification of the chorale melody. The lower three parts, entering two beats after the sopranos, stand apart in a block with their own rhythmic pattern.

Liebster Gott, wenn werd’ ich sterben? Meine Zeit läuft immer hin.

Und des allen Adams Erben, unter denen ich auch bin,

haben dies zum Vaterteil, dass sie eine kleine Weil’

arm und elend sein auf Erden und dann selber Erde werden.

Dearest God, when will I die? My time is running out.

And all of Adam’s heirs, of which I also am one,

have this for a heritage, that they are poor and wretched

for a short time on earth and then will themselves become earth.

Und des allen Adams Erben, unter denen ich auch bin,

haben dies zum Vaterteil, dass sie eine kleine Weil’

arm und elend sein auf Erden und dann selber Erde werden.

Dearest God, when will I die? My time is running out.

And all of Adam’s heirs, of which I also am one,

have this for a heritage, that they are poor and wretched

for a short time on earth and then will themselves become earth.

The virtuosic aria that follows asks the soul what it will cast off in its last hour as the body draws toward its rest in earth. The tenor soloist is accompanied by the perpetual motion of a solo oboe d’amore. (The tenor’s beginning phrase recalls the opening line, “Wann kommst du, mein Heil” from a lovely duet that appeared seven years later in Cantata 140, in another instance of a soul longing for its companion.) Although lacking flute and one oboe d’amore, the still-rich embroidery of music here suggests the soul has an abundance of goods. No wonder that the following recitative struggles with end-of-life details!

Was willst du dich, mein Geist, entsetzen, wenn meine letzte Stunde schlägt? Mein Leib neigt täglich sich zur Erden, und da muss seine Ruh’statt werden, wohin man so viel tausend trägt.

My soul, what do you want to jettison when my last hour strikes? My body daily bends toward the earth, to which one bears so many thousand, and there must my resting place be.

My soul, what do you want to jettison when my last hour strikes? My body daily bends toward the earth, to which one bears so many thousand, and there must my resting place be.

The ensuing recitative is troubled by what will become of body and goods (the believer hasn’t executed his will yet?).

Zwar fühlt mein schwaches Herz Furcht, Sorgen, Schmerz: wo wird mein Leib die Ruhe finden?

Wer wird die Seele doch von aufgelegtem Sündenjoch befreien und entbinden?

Das Meine wird zerstreut, und wohin warden meine Lieben in ihrer Traurigkeit zerstreut vertrieben?

My faint heart well feels fear, trouble, pain; where will my body find rest?

Who will release and set free the soul from the yoke of sin laid on it?

My belongings will be scattered, and to where would my dear ones be scattered in their distracted sorrow?

Wer wird die Seele doch von aufgelegtem Sündenjoch befreien und entbinden?

Das Meine wird zerstreut, und wohin warden meine Lieben in ihrer Traurigkeit zerstreut vertrieben?

My faint heart well feels fear, trouble, pain; where will my body find rest?

Who will release and set free the soul from the yoke of sin laid on it?

My belongings will be scattered, and to where would my dear ones be scattered in their distracted sorrow?

As if to decide the matter, the next aria, a tour de force for bass soloist and lively flute obbligato, cheerfully tosses off those foolish cares, looking forward to meeting Jesus and rejecting worldly possessions so as to be “transfigured and splendid” before Jesus. The meter and jaunty jig rhythm infuse the music with the joy and lightness of being of one who anticipates throwing off burdensome worldly possessions.

Doch weichet ihr tollen vergeblichen Sorgen!

Mich rufet mein Jesus: wer sollte nicht gehn?

Nichts, was mir gefällt, besitzet die Welt!

Erscheine mir seliger fröhlicher Morgen, verkläret und herrlich vor Jesu zu stehn.

Oh, soften, you foolish useless sorrows!

My Jesus calls me—who shouldn’t go?

The world possesses nothing that pleases me.

Appear to me, blessed happy morning, to stand before Jesus transfigured and splendid.

Mich rufet mein Jesus: wer sollte nicht gehn?

Nichts, was mir gefällt, besitzet die Welt!

Erscheine mir seliger fröhlicher Morgen, verkläret und herrlich vor Jesu zu stehn.

Oh, soften, you foolish useless sorrows!

My Jesus calls me—who shouldn’t go?

The world possesses nothing that pleases me.

Appear to me, blessed happy morning, to stand before Jesus transfigured and splendid.

In the following recitative, the believer bequeaths his weakness (of faith) and his belongings to the world he is leaving in favor of eternal life.

Behalte nur o Welt das Meine!

Du nimst ja selbst mein Fleisch und mein Gebeine, so nimm auch meine Armut hin; genug, dass mir aus Gottes Überfluss das höchste Gut noch werden muss, genug dass ich dort reich und selig bin.

Was aber ist von mir zu erben, als meines Gottes Vatertreu?

Die wird ja alle Morgen neu, und kann nicht sterben.

O world, keep my goods!

You surely take my flesh and my bones, so take away my weakness as well.

It is enough that the highest good from God’s abundance must yet be for me, enough that I am rich and blessed there.

But what will I inherit as my God’s fatherly trust?

It will indeed be renewed every morning, and cannot die.

Du nimst ja selbst mein Fleisch und mein Gebeine, so nimm auch meine Armut hin; genug, dass mir aus Gottes Überfluss das höchste Gut noch werden muss, genug dass ich dort reich und selig bin.

Was aber ist von mir zu erben, als meines Gottes Vatertreu?

Die wird ja alle Morgen neu, und kann nicht sterben.

O world, keep my goods!

You surely take my flesh and my bones, so take away my weakness as well.

It is enough that the highest good from God’s abundance must yet be for me, enough that I am rich and blessed there.

But what will I inherit as my God’s fatherly trust?

It will indeed be renewed every morning, and cannot die.

In the final chorale, the believer prays for a courageous spirit in death and burial in honor. The setting of this chorale verse is devoid of the external “stuff” that enriched previous movements.

Herrscher über Tod und Leben, mach’ einmal mein Ende gut,

lehre mich den Geist aufgeben, mit recht wohl gefasstem Mut!

Hilf dass ich ein ehrlich Grab, neben frommen Christen hab,

und auch endlich in der Erde nimmermehr zu Schanden werde.

Ruler over Death and Life, one day make my death good;

teach me to give up my spirit with right good courage!

Help me to have an honorable grave near pious Christians,

and also, finally in the earth, nevermore to be disgraced.

lehre mich den Geist aufgeben, mit recht wohl gefasstem Mut!

Hilf dass ich ein ehrlich Grab, neben frommen Christen hab,

und auch endlich in der Erde nimmermehr zu Schanden werde.

Ruler over Death and Life, one day make my death good;

teach me to give up my spirit with right good courage!

Help me to have an honorable grave near pious Christians,

and also, finally in the earth, nevermore to be disgraced.

Prelude and Fugue in B-minor, BWV 544

One of only a handful of organ prelude/fugue sets Bach wrote in Leipzig, BWV 544 has many memorable features. The prelude is among the most dramatic, featuring the powerful role of the pedals, which set German Baroque organ music apart from that of other nations. The prelude begins with a downward cascade that is soon met by a syncopated pedal figure of upward octave leaps. After a development of this opening topic, a new, lighter idea is given in the manuals. The two then tussle through different keys before the first idea returns to end the prelude.

After the rhythmic drive and harmonic tensions of the prelude, the fugue subject seems solid and trustworthy. Its regular, even notes move upward and back down again over a modest range. Gone are the syncopations and flashes of high drama; the pedals are generally assimilated more comfortably into the ensemble. As in the prelude, there is a lighter section for manuals. The return of the pedals is neatly prepared harmonically; now they have distinct activity, urging the drive to the conclusion.

After the rhythmic drive and harmonic tensions of the prelude, the fugue subject seems solid and trustworthy. Its regular, even notes move upward and back down again over a modest range. Gone are the syncopations and flashes of high drama; the pedals are generally assimilated more comfortably into the ensemble. As in the prelude, there is a lighter section for manuals. The return of the pedals is neatly prepared harmonically; now they have distinct activity, urging the drive to the conclusion.

Chaconne in D-minor (conclusion of Violin Partita 2, BWV 1004)

Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin (it needs no other identification!) is at once so powerful, so profound, and so intriguing that many composers have fallen under its spell. Among them are Brahms, Raff, and Busoni, who transcribed and adapted it for piano (Brahms, for left hand alone), Mendelssohn and Schumann, who transcribed it for violin and piano, and Stokowski who orchestrated it. The Chaconne is the final movement of the second of three partitas (dance suites), each of which has a companion church sonata (with no dance movements), all six for solo violin. The three sonatas are thought to have been completed by 1718 while Bach served in Cöthen (1717-1723). They are remarkable in that Bach wrote out the ornamentation rather than using the traditional symbols for ornaments or leaving the elaboration to the whim of the performer. In 1720 Bach wrote the new partitas and joined them to the sonatas, in fair copy on paper acquired from the Karlsbad region in Germany. His dated title page for the set reads: “Sei Solo. à Violino senza Basso accompagnato”.

A brief word about the baroque violin is in order here for a better understanding of the instrument for which Bach wrote those six works. In general, the violin of his time sounded less bright, perhaps warmer, than that of today’s violin, because the strings then were gut rather than steel, and the tension on them was much less. Further, the bow was arched outward (convex) rather than inward toward the hair (concave), and the tension on the hair was less than in a modern bow. Contrapuntal lines were easier to perform and fuller chords were possible because the arch of the bridge supporting the strings above the face of the violin was lower, which meant that multiple stops of more than two strings were easier to achieve. Delicate, intricate ornaments were easier to produce because the strings were lower against the neck, and the neck was at a lower angle against the body of the violin. All of these elements of the baroque violin facilitated an 18th-century performer’s execution of technically complex works like the Chaconne and allowed for subtle dynamic nuances that complemented the dramatic and rhetorical practices of the time. Today, a violinist using a modern instrument creates a necessarily different, though equally valid, performance of Bach’s music for solo violin.

A brief word about the baroque violin is in order here for a better understanding of the instrument for which Bach wrote those six works. In general, the violin of his time sounded less bright, perhaps warmer, than that of today’s violin, because the strings then were gut rather than steel, and the tension on them was much less. Further, the bow was arched outward (convex) rather than inward toward the hair (concave), and the tension on the hair was less than in a modern bow. Contrapuntal lines were easier to perform and fuller chords were possible because the arch of the bridge supporting the strings above the face of the violin was lower, which meant that multiple stops of more than two strings were easier to achieve. Delicate, intricate ornaments were easier to produce because the strings were lower against the neck, and the neck was at a lower angle against the body of the violin. All of these elements of the baroque violin facilitated an 18th-century performer’s execution of technically complex works like the Chaconne and allowed for subtle dynamic nuances that complemented the dramatic and rhetorical practices of the time. Today, a violinist using a modern instrument creates a necessarily different, though equally valid, performance of Bach’s music for solo violin.

More information about baroque violins: www.TheMonteverdiViolins.org/baroque-violin

What accounts for the fascination with this famous Chaconne? It is a technically very demanding set of 64 events involving several statements of a “theme”, which is a harmonic progression, and variations on it; it’s a sarabande, a triple-meter dance that originated in the Spanish New World but was ultimately banned in Spain for its lascivious nature; and it’s a movement in three sections (D minor, D major, D minor). But it also shows Bach’s frequent use of number symbolism and gematria (number codes referring to letters) in music, his practice of adapting earlier compositions into new works, and his vast store of sacred music from his life-long devotion to God in the service of the Lutheran church. Recent scholars see the Chaconne as a reflection of the heartrending circumstances in which Bach completed the three violin partitas: in early summer 1720 he had accompanied his employer on a three-month long trip to Karlsbad, but upon returning home he learned that his beloved wife of thirteen years, Maria Barbara, had suddenly become ill and died only days earlier. The Chaconne, especially, appears to be deeply expressive of grief. In 1985 Helga Thoene, a violin teacher at the University of Düsseldorf, began presenting remarkable studies that showed a very personal dimension of the six solo violin works. Her Bach tri-centennial conference paper explored number and theological symbols in the solo violin sonatas and partitas. She explained that the three sonatas conform to the three major liturgical feasts of Christianity: Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, evidenced by chorale quotations embedded in the sonatas, linking them to these feasts. She pointed out that three ancient faith statements are associated with the feasts: “Ex Deo nascitur, in Christo morimur, per Spiritum Sanctum reviviscimus”—“We are born from God, we die in Christ, we are reborn through the Holy Spirit”. The paired sonatas and partitas of the complete set parallel the three statements; the second sonata and its companion partita are thus associated with Easter.

Then, in 1994 Thoene published her study of the Chaconne itself, revealing embedded quotations of Lutheran chorale melodies which, along with number codes in the work, pointed to Bach’s having purposed the music as an elegy for Maria Barbara. Perhaps the title of the set of sonatas and partitas further supports this idea; “Sei solo”, as Bach wrote it, means “You are alone”. Details of Bach’s notation reveal chorale phrases embedded in the Chaconne; many allude to death. In fact, the opening and concluding phrases of the chorale tune “Christ lag in Todesbanden”—“Christ lay in death’s bonds”—are present in slow notes within the Chaconne. Another quote is from the second chorale verse setting in Cantata 4, in which Death has enchained all humanity. Thoene’s analysis shows the Chaconne also contains phrases from other chorales, praising God, expressing faith and trust in God, pleading for help and patience, and more. Besides chorale melodies, Bach also used a well-known device of a descending 4-note motif associated with grief within the music’s texture. The symbolic inner life of the Chaconne is endlessly rich. One would do well to find the recording that explores it: “Morimur”, with The Hilliard Ensemble and Christoph Poppen (EMC), source of the information above on Professor Thoene’s research.

BWV 4: Christ lag in Todesbanden

Cantata 4, Christ lag in Todesbanden (Christ Lay in the Death’s Bonds) is a seven-movement setting of the Lutheran Easter chorale of the same name, preceded by a short instrumental introduction, or sinfonia. Because all movements contain the chorale melody and text, this cantata is termed a chorale cantata. It is the only one of its type that Bach wrote. It is also full of examples of Bach’s use of music as symbolic medium. Bach composed this cantata for Easter, 1707, while he was at Mühlhausen. Nearly two decades later, in 1724, as newly-appointed cantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, he had the parts recopied, with some revisions especially to the orchestration. The cantata was performed at the church at Leipzig University on Easter Day in 1724 and 1725.

“Christ lag in Todesbanden” is one of several chorales (hymns) for which none other than Martin Luther wrote both the German text and the melody in the first half of the 16th century. He adapted both text and melody from a much older Latin plainchant from the Catholic liturgy for Easter, the sequence prosa “Victimae paschali laudes”, ascribed to Vipo in the first half of the eleventh century. To create this chorale, Luther intermixed scriptural passages with passages from the sequence text, all in German so that his congregation would understand what they were singing. He kept a significant, identifiable portion of the music of the old sequence, creating what is termed a contrafactum—literally a “made-over” melody. Luther set up the chorale in seven verses, which form an arch with the fourth verse as the midpoint. The contents of verses on one side of the midpoint are mirrored in introversion on the other side, forming a chiasm—a cross relationship. In this way Luther was able to show a spiritual meaning and draw theological connections. Luther was well aware of the Jewish celebrations of Passover and Yom Kippur, and also of alchemy and its Christian symbolism. The text of “Christ lag in Todesbanden” appears also to have interwoven allusions to the week-long alchemical process. Bach’s treatment of the chorale amplifies Luther’s theological foundation.

“Christ lag in Todesbanden” is one of several chorales (hymns) for which none other than Martin Luther wrote both the German text and the melody in the first half of the 16th century. He adapted both text and melody from a much older Latin plainchant from the Catholic liturgy for Easter, the sequence prosa “Victimae paschali laudes”, ascribed to Vipo in the first half of the eleventh century. To create this chorale, Luther intermixed scriptural passages with passages from the sequence text, all in German so that his congregation would understand what they were singing. He kept a significant, identifiable portion of the music of the old sequence, creating what is termed a contrafactum—literally a “made-over” melody. Luther set up the chorale in seven verses, which form an arch with the fourth verse as the midpoint. The contents of verses on one side of the midpoint are mirrored in introversion on the other side, forming a chiasm—a cross relationship. In this way Luther was able to show a spiritual meaning and draw theological connections. Luther was well aware of the Jewish celebrations of Passover and Yom Kippur, and also of alchemy and its Christian symbolism. The text of “Christ lag in Todesbanden” appears also to have interwoven allusions to the week-long alchemical process. Bach’s treatment of the chorale amplifies Luther’s theological foundation.

Here is a guide to the setting of the text in Cantata 4:

With brief hints of the chorale melody, the short Sinfonia foreshadows the cantata’s story. At its conclusion, it shows us in musical gesture the elevation of Jesus to the cross, the loneliness of his death agony, his deposition from the cross, and even his being placed in a low resting place—a burial. Alchemically speaking, this condition is the base material, the “worst case scenario” which, through several procedures, will be turned into the imperishable “Perfection”.

With brief hints of the chorale melody, the short Sinfonia foreshadows the cantata’s story. At its conclusion, it shows us in musical gesture the elevation of Jesus to the cross, the loneliness of his death agony, his deposition from the cross, and even his being placed in a low resting place—a burial. Alchemically speaking, this condition is the base material, the “worst case scenario” which, through several procedures, will be turned into the imperishable “Perfection”.

Verse one is a chorale fantasia, telling the resurrection story in a nutshell and summarizing the rest of the cantata. Unlike Vipo’s prosa beginning with “praise to the paschal victim”, Luther’s text has Christ already dead, “in the bonds of death”. Bach’s Verse I music shows the return of life and joy.

Christ lag in Todesbanden, für unsre Sünd gegeben.

Er ist wieder erstanden und hat uns bracht das Leben.

Des wir sollen fröhlich sein, Gott loben und ihm dankbar sein

und singen Hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Christ lay in Death’s bonds, given for our sins.

He has risen again and has brought us life.

So we shall be joyful, praise God and be thankful to him,

and sing hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Er ist wieder erstanden und hat uns bracht das Leben.

Des wir sollen fröhlich sein, Gott loben und ihm dankbar sein

und singen Hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Christ lay in Death’s bonds, given for our sins.

He has risen again and has brought us life.

So we shall be joyful, praise God and be thankful to him,

and sing hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Verse two, dark and despairing, is devoted to describing the power of Death, the alchemical “blackened” stage. Over a strutting bass, analogous to Death, soprano and alto voices writhe and clash in a description of sin, often engaging in tight dissonances. The voices try to break free but can’t. Even the Hallelujah is in chains (of suspensions).

Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt bei allen Menschenkindern,

Das macht’ alles unsre Sünd, kein Unschuld war zu finden.

Davon kam der Tod so bald und nahm über uns Gewalt, hielt uns

in seinem Reich gefangen. Hallelujah!

Among all the children of mortals, no one could conquer Death;

Our sin did all this; there was no innocence to be found.

Therefore Death came so suddenly and took power over us,

held us captive in his kingdom. Hallelujah!

Das macht’ alles unsre Sünd, kein Unschuld war zu finden.

Davon kam der Tod so bald und nahm über uns Gewalt, hielt uns

in seinem Reich gefangen. Hallelujah!

Among all the children of mortals, no one could conquer Death;

Our sin did all this; there was no innocence to be found.

Therefore Death came so suddenly and took power over us,

held us captive in his kingdom. Hallelujah!

Verse three tells of the coming of Jesus to undergo Death as a substitute for our having to do so (a connection to the sacrificial lamb of Yom Kippur), and reminds us that all that remains of Death is a powerless image. The brilliant violin solo suggests the confident vigor of a hero riding in to save the day. When the tenor sings that Death has lost all its “rights and power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image”, the violin actually comes to a halt. When the tenor completes the phrase “da bleibet nichts” –“so nothing remains”—there is silence—nothing—in the music. The tenor sings the rest of the phrase, “denn Tods Gestalt” –“than Death’s image”. The word Tods is held out while the violin provides a cruciform figure above it, and the tenor echoes it. A firm cadence marks the end of the power of Death. The text resumes, and the verse concludes in a bright, joyful Allegro tempo.

Jesus Christus, Gottes Sohn, an unser Statt ist kommen,

Und hat die Sünde weggetan, damit dem Tod genommen

All sein Recht und sein Gewalt, da bleibet nichts denn Tods Gestalt,

den Stachl hat er verloren. Hallelujah!

Jesus Christ, God’s son, has come in our place

And done away with sins, and with that took away

All Death’s rights and its power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image,

Death has lost his thorn. Hallelujah!

Und hat die Sünde weggetan, damit dem Tod genommen

All sein Recht und sein Gewalt, da bleibet nichts denn Tods Gestalt,

den Stachl hat er verloren. Hallelujah!

Jesus Christ, God’s son, has come in our place

And done away with sins, and with that took away

All Death’s rights and its power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image,

Death has lost his thorn. Hallelujah!

Verse four, the pivot point of the cantata, describes the great battle between Life and Death and the ultimate defeat of Death. Within this fugal chorale fantasy, the great chorale melody in longer notes holds constant in the alto part, a kind of internal anchor. At the text “ein Tod den andern frass”—“one Death gobbled up another”--Bach has the voices in canon literally bringing an end to themselves.

Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg, da Tod und Leben rungen,

Das Leben behielt den Sieg, es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündiget das, wie ein Tod den andern frass,

ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden. Hallelujah!

It was an astonishing war, when Death and Life struggled.

Life secured the victory, it has swallowed up Death.

Scripture had proclaimed this, how one Death gobbled up another,

A mockery has been made of Death. Hallelujah!

Das Leben behielt den Sieg, es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündiget das, wie ein Tod den andern frass,

ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden. Hallelujah!

It was an astonishing war, when Death and Life struggled.

Life secured the victory, it has swallowed up Death.

Scripture had proclaimed this, how one Death gobbled up another,

A mockery has been made of Death. Hallelujah!

Verse five is the converse of Verse three. It reveals the Easter Lamb “roasted in fervent love”—suggesting the calcination stage of the alchemical work. The descending continuo passage begins each line of text, reflecting the passion of Jesus’s sacrificial death. Bach incorporates a marvelous image of Death by placing it for the singer on a horrendously low pitch approached by a “killer” leap. In the next phrase only a few measures later, Bach sets the word “Würger”—“destroyer”—at the high end of the singer’s range, and held out for four measures. One translation of “Würger” is “strangler”, which certainly could apply to this music if the singer isn’t careful. (And you thought Bach had no sense of humor!)

Hier ist das rechte Osterlamm, davon Gott hat geboten,

Das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm in heisser Lieb gebraten,

Das Blut zeichnet unsre Tür, das halt der Glaub dem Tode für,

der Würger kann uns nicht mehr schaden. Hallelujah!

Here is the true Easter lamb that God has presented,

That is roasted in ardent love high on the trunk of the cross.

The blood marks our door, faith holds it up against Death.

The Destroyer can harm us no more. Hallelujah!

Das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm in heisser Lieb gebraten,

Das Blut zeichnet unsre Tür, das halt der Glaub dem Tode für,

der Würger kann uns nicht mehr schaden. Hallelujah!

Here is the true Easter lamb that God has presented,

That is roasted in ardent love high on the trunk of the cross.

The blood marks our door, faith holds it up against Death.

The Destroyer can harm us no more. Hallelujah!

Verse six is bathed in light and life, the converse of Verse two; the work of deliverance from Death has been achieved. Alchemically, we have now achieved the “Perfection”, the complete transmutation of the base material into imperishable “Gold”. The bright soprano and tenor voices suggest the brilliance of the Sun which is the Lord, illuminating the hearts of those at the feast. The dancing quality to the movement underscores the celebratory text.

So feiern wir das hohe Fest mit Herzensfreud und Wonne,

Das uns der Herre [er]scheinen lässt, er ist selber die Sonne,

Der durch seiner Gnade Glanz erleuchtet unsre Herzen ganz,

Der Sünden Nacht ist verschwunden. Hallelujah!

The Lord makes it present to us, he himself is the sun,

So we celebrate the high feast with joyful heart and ecstasy,

Who through the radiance of his grace completely illumines our hearts.

The night of sin has disappeared. Hallelujah!

Das uns der Herre [er]scheinen lässt, er ist selber die Sonne,

Der durch seiner Gnade Glanz erleuchtet unsre Herzen ganz,

Der Sünden Nacht ist verschwunden. Hallelujah!

The Lord makes it present to us, he himself is the sun,

So we celebrate the high feast with joyful heart and ecstasy,

Who through the radiance of his grace completely illumines our hearts.

The night of sin has disappeared. Hallelujah!

Verse seven would in Bach’s time have been sung by the congregation, thus forming the alchemical “Projection”, the continuation of the Believer’s life after deliverance from Death. The Christian prospers (eats well, lives well) on the life-giving food (the Eucharistic bread). The old leaven, the yeast from the previous batch of sourdough, the old way of life, will not be present, because the new grace supplants it. The soul will be sustained only by the new spiritual food. This verse not only sums up the story previewed in verse one but affirms a continuation beyond the experiences reflected in the chorale itself, as the Believer goes out into the world, transformed by the passage into life, secure in spiritual immortality.

Wir essen und leben wohl in rechten Osterfladen,

Der alte Sauerteig nicht soll sein bei dem Wort der Gnaden,

Christus will die Koste sein und speisen die Seele allein,

der Glaub will keins andern leben. Hallelujah.

We eat and live well on the true Passover bread.

The old leaven shall not exist beside the word of grace;

Christ will be the food and alone feed the soul,

Faith will live by no other. Hallelujah!

Der alte Sauerteig nicht soll sein bei dem Wort der Gnaden,

Christus will die Koste sein und speisen die Seele allein,

der Glaub will keins andern leben. Hallelujah.

We eat and live well on the true Passover bread.

The old leaven shall not exist beside the word of grace;

Christ will be the food and alone feed the soul,

Faith will live by no other. Hallelujah!

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2014

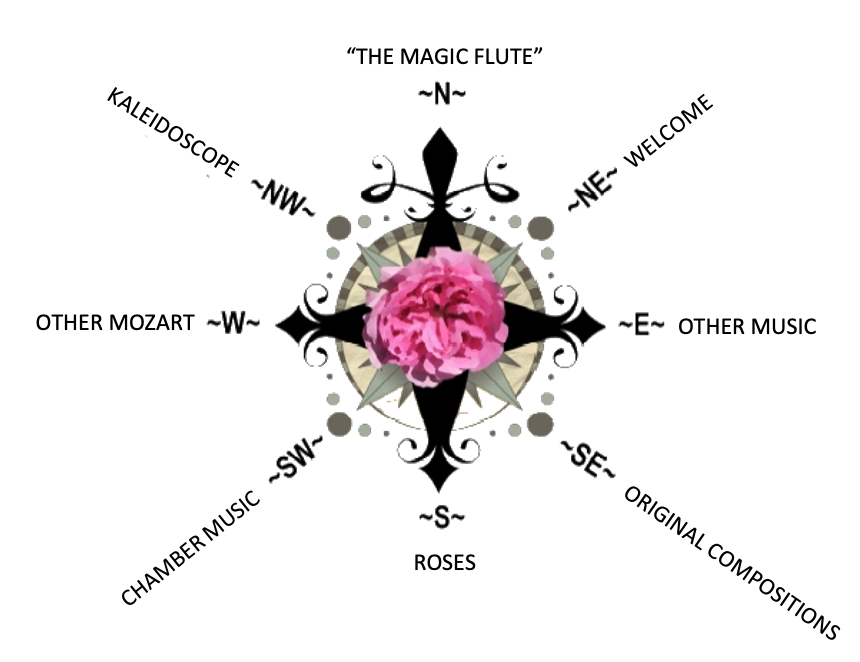

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.