- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

"THE MAGIC FLUTE" ORIGINAL PRODUCTION

by Judith Eckelmeyer

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Librettists: Emanuel Schikaneder, Karl Ludwig Giesecke, and likely others.

Libretto published 1791 by Ignaz Alberti, Vienna

Libretto published 1791 by Ignaz Alberti, Vienna

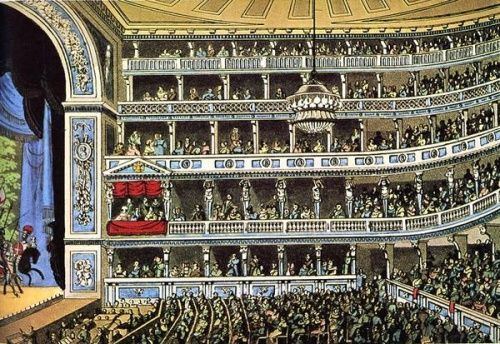

Location: Theater auf der Wieden, outside the walls of Vienna

Date of Premiere: September 30, 1791

Stage Director: Karl Ludwig Giesecke

CHARACTERS AND PERFORMERS IN THE ORIGINAL PRODUCTION

Sarastro (bass), leader of the Initiates in the Temple of Isis and Osiris: Franz Xaver Gerl

Tamino (tenor), a prince: Benedikt Schack

Speaker in the Temple of Wisdom (bass): Mr. Winter

First Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (bass): Urban Schikaneder (elder brother of Emanuel)

Second Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (tenor): Johann Michael Kistler

Third Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (speaking role): Christian Hieronymus Moll

Queen of the Night (soprano): Josepha Hofer, sister of Mozart’s wife Constanze

Pamina, daughter of the Queen of the Night (soprano): Anna Gottlieb

First Lady (soprano): Miss Klöpfer

Second Lady (soprano): Miss Hofmann

Third Lady (alto): Elizabeth Schack, wife of Benedikt Schack

Papageno (baritone): Emanuel Schikaneder

An Old Woman (Papagena) (soprano): Barbara Gerl, wife of Franz Xaver Gerl

Monostatos, Pamina’s overseer in Sarastro’s realm (tenor): Johann Joseph Nouseul

First Slave: Karl Ludwig Giesecke (aka Georg Metzler)

Second Slave: Wilhelm Frasel

Third Slave: Johann Nikolaus Starke

First Boy (soprano): Anna (Nannette) Schikaneder, Urban’s daughter

Second Boy (soprano): Young Tuscher

Third Boy (alto): Young Handelgruber

Chorus of Slaves, Priests, and Followers of Sarastro

Sarastro (bass), leader of the Initiates in the Temple of Isis and Osiris: Franz Xaver Gerl

Tamino (tenor), a prince: Benedikt Schack

Speaker in the Temple of Wisdom (bass): Mr. Winter

First Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (bass): Urban Schikaneder (elder brother of Emanuel)

Second Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (tenor): Johann Michael Kistler

Third Priest in the Temple of Wisdom (speaking role): Christian Hieronymus Moll

Queen of the Night (soprano): Josepha Hofer, sister of Mozart’s wife Constanze

Pamina, daughter of the Queen of the Night (soprano): Anna Gottlieb

First Lady (soprano): Miss Klöpfer

Second Lady (soprano): Miss Hofmann

Third Lady (alto): Elizabeth Schack, wife of Benedikt Schack

Papageno (baritone): Emanuel Schikaneder

An Old Woman (Papagena) (soprano): Barbara Gerl, wife of Franz Xaver Gerl

Monostatos, Pamina’s overseer in Sarastro’s realm (tenor): Johann Joseph Nouseul

First Slave: Karl Ludwig Giesecke (aka Georg Metzler)

Second Slave: Wilhelm Frasel

Third Slave: Johann Nikolaus Starke

First Boy (soprano): Anna (Nannette) Schikaneder, Urban’s daughter

Second Boy (soprano): Young Tuscher

Third Boy (alto): Young Handelgruber

Chorus of Slaves, Priests, and Followers of Sarastro

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

The Bohemian Connection:

Images of the Magic Flute in the Time of its Creation

|

...during Papageno's aria with the glockenspiel I went behind the scenes, as I felt a sort of impulse today to play it myself. Well, just for fun, at the point where Schikaneder has a pause, I played an arpeggio. This time he stopped and refused to go on. I guessed what he was thinking and again played a chord. He then struck the glockenspiel and said 'Shut up'. Whereupon everyone laughed. I am inclined to think that this joke taught many of the audience for the first time that Papageno does not play the instrument himself. (Mozart to Constanze, October 8-9, 1791.) |

... study of another facet of the opera's existence will yield further insights into the meaning of the work for its own time. This facet, complementing the text, plot and music, is the visual dimension, the spectacle of the stage events which the audience would be witnessing as the text and music run their course.

The visual aspect of the opera is somewhat difficult to trace, for there has been no illustration or other record of the scenery, costumes, props or stage equipment of the original production in Vienna's Freihaustheater auf der Wieden. The libretto which is believed to have in it Giesecke's stage directions contains virtually no information that has not already appeared in the printed libretto.

What very little we do know about the original production in the first month or so of its run is that there was plenty of visual entertainment, most of it probably improvised by Schikaneder in the role of Papageno. This fact, of course, is clear from Mozart's letter in which he describes his own deliberate mistiming of the glockenspiel chord and Schikaneder's response. Mozart's comment that until that moment the audience believed Schikaneder/Papageno actually played the music on the stage-prop bells bespeaks an extraordinarily gullible public in attendance that night-or perhaps until that night. What must they have thought of the rest of the stage effects? Mozart's comment reveals, first, the level of the audience's awareness of the subtleties within the opera that its creators must have been dealing with, perhaps anticipating, and, second, the amount of time that it must have taken for the general public to perceive the depth of what they witnessed as pure entertainment.

Given the dearth of contemporary eyewitness information and documents pertaining to the first production in Vienna, one must consult other visual records from the period. The closest we can come to Schikaneder's production is through illustrations of stage settings and characters in costume, all of which date from after 1791, and from productions other than the original. Problems exist in dealing with stage designs. Certainly they represent the inevitable changes that occur from one production to another, from one stage to another, from one time to another. It is unlikely that all details of the original production could or would be reconstructed from even a second-generation production for the same theater (even if, for instance, the Freihaustheater had not been demolished and were available for such a production). Nevertheless, some intriguing and provocative pieces of information emerge from these sources, and will help to confirm ideas stated previously about the opera and its creators.

Very soon after the opening of the first production in Vienna (September 30, 1791), the opera was mounted in several other cities. Both Leipzig and Munich adopted the work in 1793, with designs by Johann Baptist Klein and Giuseppe Quaglio respectively. All that is extant from a Hamburg production of 1793 is an almanac of engravings of scenes from the opera. in 1794, Christian August Vulpius reworked the libretto extensively (to "clarify" it) for the Weimar production, for which there exists an illustration by Georg Melchior Kraus of the costumed actors' backstage activities.

The earliest production of the original version of the opera outside of Vienna, however, was mounted in Prague, capital of Bohemia, on October 25, 1792. This would have meant a performance in German, very likely with stage designs and costumes replicating those of Schikaneder's Freihaustheater production. Two years later, Prague saw not only an Italian-language production, using Scipione Piattoli's translation, but also the first Czech-language performance. The original 1791 Viennese production or its 1792 version in Prague evidently generated productions by Karl Hain's company in the nearby cities of Brno (Brünn) in 1793 and Olomouc (Olmütz) in 1794. Prague was the location of the three different language productions within two years' time, beginning only a year after the Viennese premiere. Historically, Prague had been the focus of Bohemian government and tradition and the principal city of Czech lands, that is, Bohemia and Moravia. However, Brno and Olomouc, in Moravia, east of the Bohemian sector of the country, were also important centers of Czech historical traditions. The timing and location of the five early productions of The Magic Flute in Bohemian lands have considerable significance: They all fall after the death of Leopold II, on March 1, 1792, and thus during the reign of his son, Francis II. Further, it was for the Brno and Olomouc productions that a set of illustrations of the opera was created. These illustrations will have a bearing on our further understanding of the work.

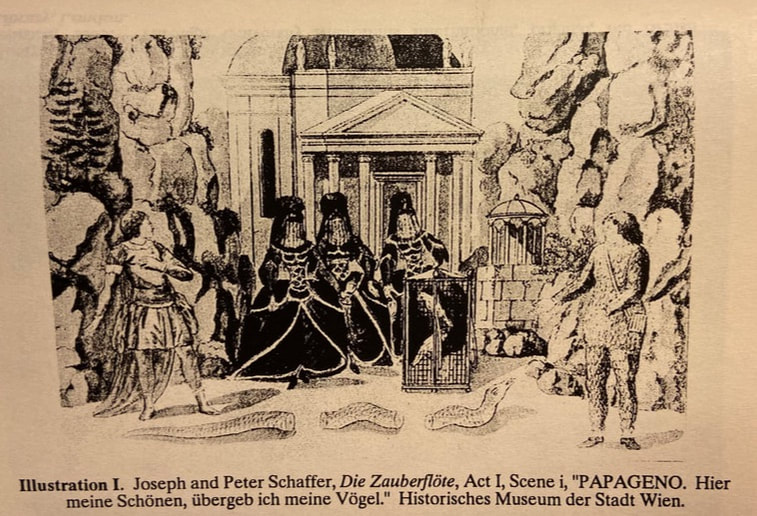

In 1795 there appeared in the Allgemeines Europäisches Journal in Brno a series of six engraved and colored illustrations of The Magic Flute by Josef and Peter Schaffer. The illustrations are believed to have been created about 1793, well before their journal publication but certainly after the 1792 Prague production of the opera. Perhaps for this reason, they are believed to depict the production by Karl Hain's company in Brno and Olomouc. However, the illustrations very probably bear some relation to the Vienna production, for they contain numerous details mentioned in the printed libretto of 1791; furthermore,, they each bear captions, in German, duplicating exactly the text from the corresponding scenes in the 1791 printed libretto. These facts suggest that they may represent in some degree the original Viennese production mounted under Schikaneder's direction; whether they derived literally from the 1791 Vienna performance or that of 1792 in Prague is impossible to determine. On the other hand, three of the illustrations reflect a production that may well be Hain's, not Schikaneder's, because they reveal details that deviate significantly from the stage directions in the 1791 libretto; and the German-language captions would not be out of place because German was still the official language in Bohemia at the time These three particular scenes shed light on the opera's early performance history as well as its cultural ties.

The visual aspect of the opera is somewhat difficult to trace, for there has been no illustration or other record of the scenery, costumes, props or stage equipment of the original production in Vienna's Freihaustheater auf der Wieden. The libretto which is believed to have in it Giesecke's stage directions contains virtually no information that has not already appeared in the printed libretto.

What very little we do know about the original production in the first month or so of its run is that there was plenty of visual entertainment, most of it probably improvised by Schikaneder in the role of Papageno. This fact, of course, is clear from Mozart's letter in which he describes his own deliberate mistiming of the glockenspiel chord and Schikaneder's response. Mozart's comment that until that moment the audience believed Schikaneder/Papageno actually played the music on the stage-prop bells bespeaks an extraordinarily gullible public in attendance that night-or perhaps until that night. What must they have thought of the rest of the stage effects? Mozart's comment reveals, first, the level of the audience's awareness of the subtleties within the opera that its creators must have been dealing with, perhaps anticipating, and, second, the amount of time that it must have taken for the general public to perceive the depth of what they witnessed as pure entertainment.

Given the dearth of contemporary eyewitness information and documents pertaining to the first production in Vienna, one must consult other visual records from the period. The closest we can come to Schikaneder's production is through illustrations of stage settings and characters in costume, all of which date from after 1791, and from productions other than the original. Problems exist in dealing with stage designs. Certainly they represent the inevitable changes that occur from one production to another, from one stage to another, from one time to another. It is unlikely that all details of the original production could or would be reconstructed from even a second-generation production for the same theater (even if, for instance, the Freihaustheater had not been demolished and were available for such a production). Nevertheless, some intriguing and provocative pieces of information emerge from these sources, and will help to confirm ideas stated previously about the opera and its creators.

Very soon after the opening of the first production in Vienna (September 30, 1791), the opera was mounted in several other cities. Both Leipzig and Munich adopted the work in 1793, with designs by Johann Baptist Klein and Giuseppe Quaglio respectively. All that is extant from a Hamburg production of 1793 is an almanac of engravings of scenes from the opera. in 1794, Christian August Vulpius reworked the libretto extensively (to "clarify" it) for the Weimar production, for which there exists an illustration by Georg Melchior Kraus of the costumed actors' backstage activities.

The earliest production of the original version of the opera outside of Vienna, however, was mounted in Prague, capital of Bohemia, on October 25, 1792. This would have meant a performance in German, very likely with stage designs and costumes replicating those of Schikaneder's Freihaustheater production. Two years later, Prague saw not only an Italian-language production, using Scipione Piattoli's translation, but also the first Czech-language performance. The original 1791 Viennese production or its 1792 version in Prague evidently generated productions by Karl Hain's company in the nearby cities of Brno (Brünn) in 1793 and Olomouc (Olmütz) in 1794. Prague was the location of the three different language productions within two years' time, beginning only a year after the Viennese premiere. Historically, Prague had been the focus of Bohemian government and tradition and the principal city of Czech lands, that is, Bohemia and Moravia. However, Brno and Olomouc, in Moravia, east of the Bohemian sector of the country, were also important centers of Czech historical traditions. The timing and location of the five early productions of The Magic Flute in Bohemian lands have considerable significance: They all fall after the death of Leopold II, on March 1, 1792, and thus during the reign of his son, Francis II. Further, it was for the Brno and Olomouc productions that a set of illustrations of the opera was created. These illustrations will have a bearing on our further understanding of the work.

In 1795 there appeared in the Allgemeines Europäisches Journal in Brno a series of six engraved and colored illustrations of The Magic Flute by Josef and Peter Schaffer. The illustrations are believed to have been created about 1793, well before their journal publication but certainly after the 1792 Prague production of the opera. Perhaps for this reason, they are believed to depict the production by Karl Hain's company in Brno and Olomouc. However, the illustrations very probably bear some relation to the Vienna production, for they contain numerous details mentioned in the printed libretto of 1791; furthermore,, they each bear captions, in German, duplicating exactly the text from the corresponding scenes in the 1791 printed libretto. These facts suggest that they may represent in some degree the original Viennese production mounted under Schikaneder's direction; whether they derived literally from the 1791 Vienna performance or that of 1792 in Prague is impossible to determine. On the other hand, three of the illustrations reflect a production that may well be Hain's, not Schikaneder's, because they reveal details that deviate significantly from the stage directions in the 1791 libretto; and the German-language captions would not be out of place because German was still the official language in Bohemia at the time These three particular scenes shed light on the opera's early performance history as well as its cultural ties.

The first representation shows Tamino (stage right), Papageno (stage left), the Three Ladies (center), and in front of the Ladies the slain serpent. There are flats depicting rocky hills on either side and a small Pantheon-like temple, center, behind the Three Ladies; a small round gazebo-like structure beside them seems to cover a well. The moment in the opera is Act I, Scene iii, just after Papageno has claimed to have killed the serpent, when the Ladies return to punish him and to give Tamino the portrait of Pamina. Visible in the Ladies' possession are a goblet and a large padlock, and they aren't carrying their spears.

In this illustration Papageno's features are relatively clear; he is shown with shoulder-length brown hair, beardless, but with a relatively heavy chin and jaw. Comparisons of this figure with know portraits of Schikaneder indicate that Schikaneder was the model for the illustration and lend weight to the idea that the illustration--and the set--represented at least in this aspect the production as Schikaneder acted the role of Papageno and directed it in Vienna, and perhaps in 1792 in Prague. However, Schikaneder's presence in the illustration raises an important question. Did he indeed participate in either the 1792 production in Prague or the 1793 production in Brno? He was know to have been working in Vienna toward a production of Nunziato Porta's Der Ritter Roland (Roland the Knight) in January 1792, a German translation of Don Giovanni for November 5, 1792, and a production of Der wohltätige Derwisch (The Benevolent Dervish) through the late summer of 1793. With this schedule of works for the Freyhaustheater, Schikaneder might be presumed to have been occupied with his own activities in Vienna while Prague and, later, Brno mounted The Magic Flute. If this was the case, the Schaffers' representation of him in their scenes is unauthentic to the Brno production. They were, then, either representing the personnel of the original Vienna production, which they may have seen, or they had included a portrait of Schikaneder perhaps to acknowledge his original production of the opera and his theatrical reputation as actor and producer. The degree of correlation with the original production given in these illustrations becomes a central issue in the interpretation not only of the Schaffers' engravings but also of the historical threads and meaning in the opera itself.

Other details in the Schaeffers' illustration of this scene, such as Papageno's feather-covered costume, the rocky scene, the round temple, and the veiled Ladies, conform with details of the original libretto. However, the one extraordinary detail is that the serpent has been separated into three segments, clearly cut, as if with the Ladies' spears. This detail is nowhere called for in the libretto or in Mozart's autograph score of the opera, although many later editions of it carried the instruction that the Ladies "prod the serpent apart into three pieces." Was this separation authentic to the stage business in Schikaneder's own Viennese production of 1791? Was the Schaffers' illustration of the serpent executed at Schikaneder's request or direction? Did some other member of Schikaneder's original cast--such as Franz Xaver Gerl, the original Sarastro--transmit this unrecorded detail of the first production to those in Brno or to the Schaffers? We recall that Gerl had transferred his career from Vienna to Brno in 1794, seemingly too late to influence these illustrations by the time they were published in 1795. Was this detail interpolated into the Brno production and reproduced in the illustration of the scene? Or was this vision of the serpent strictly of the Schaffers' own devising?

Unfortunately, there seems no direct way to select among theses options. However, some possibilities are raised by a tract written prior to 1626 but first published in 1657, almost a decade after the Thirty Years' War had ended. The tract, Lux in Tenebris, contains a preface by Comenius and prophecies by several authors about the great battle between light and darkness that was interpreted as the struggle between Protestant and Catholic Hapsburg forces in the Thirty Years' War. Associated with the prophecy of Christopher Kotter in this collection is an illustration showing Kotter and two angels under a tree with a glowing Lion walking before then. Behind the lion seems to be a fallen star or comet, and further in the distance another lion attacking a snake with a sword. In the sky above the lions and fallen star are another star and, below it, a serpent cut into four pieces. The illustration has to do with the text's prophetic description, which contains a blend of astrological, biblical and classical allusions. The lion is described as holding a sword in his right hand and the imperial insignia of a golden apple, in his left; he is, therefore, representing not the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, a Hapsburg whose heraldic sign was an eagle, but the Elector Palatine of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick, whose sign was a lion. The text makes it clear that this lion was also to be interpreted as the Lion of Judah, from whose collar hangs a sun, "bearing the brightness of the sun in heaven." The lion cuts up the "hypocritical" serpent with his sword in order to defend his people from it.

Unfortunately, there seems no direct way to select among theses options. However, some possibilities are raised by a tract written prior to 1626 but first published in 1657, almost a decade after the Thirty Years' War had ended. The tract, Lux in Tenebris, contains a preface by Comenius and prophecies by several authors about the great battle between light and darkness that was interpreted as the struggle between Protestant and Catholic Hapsburg forces in the Thirty Years' War. Associated with the prophecy of Christopher Kotter in this collection is an illustration showing Kotter and two angels under a tree with a glowing Lion walking before then. Behind the lion seems to be a fallen star or comet, and further in the distance another lion attacking a snake with a sword. In the sky above the lions and fallen star are another star and, below it, a serpent cut into four pieces. The illustration has to do with the text's prophetic description, which contains a blend of astrological, biblical and classical allusions. The lion is described as holding a sword in his right hand and the imperial insignia of a golden apple, in his left; he is, therefore, representing not the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, a Hapsburg whose heraldic sign was an eagle, but the Elector Palatine of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick, whose sign was a lion. The text makes it clear that this lion was also to be interpreted as the Lion of Judah, from whose collar hangs a sun, "bearing the brightness of the sun in heaven." The lion cuts up the "hypocritical" serpent with his sword in order to defend his people from it.

In her discussion of Kotter's prophecies, Frances Yates suggests that the celestial part of the scene "may possibly be an allusion to the new star in the constellation Serpentarius, referred to in the Rosicrucian Fama as foretelling new things. The lion of Kotter's vision is perhaps punishing Serpentarius for not having fulfilled the interpretation of the new star as favorable to Frederick's fortunes.

The date above the illustration is 1623, a significant year in the course of the Thirty Years' War, for in that year Frederick and the Protestant cause were suffering abject defeat in spite of what had appeared to be a propitious beginning in the Elector's political career. Frederick, having married Elizabeth in England in 1613, had returned with her to Heidelberg, Germany, and soon after was elected by the Bohemian Diet to supplant the newly crowned successor to Emperor Rudolph II of Bohemia: the Archduke Ferdinand of Styria. Ferdinand held an extreme Roman Catholic position. In addition, his kingship was based on his Hapsburg lineage under the assumption that Bohemia would be ruled hereditarily by the Hapsburgs. The Bohemian Diet, however, was largely Protestant. They deposed Ferdinand and chose Frederick to be King of Bohemia. In a time when open hostility had already been established, Frederick was faced with growing opposition by the Hapsburg empire and its Catholic allies. At the outset of what was to become the devastating Thirty Years' War, Frederick's forces, attempting to put down a rebellion of Bohemian Catholics, were defeated at the White Mountain in November of 1620.

Frederick and Elizabeth left Prague and made their way-not to the Palatinate, which by then had been invaded by armies of the Spanish Hapsburgs, but to the Netherlands, where Calvinist Protestantism was firmly established and Frederick, a Calvinist, was welcome. Elizabeth, too, was received in great favor, for there were historical ties between England and the House of Orange. In 1623, however, the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand stripped Frederick of his title of Elector, a drastic step considered illegal by most of the other Electors, since the electorate was bestowed for life. Frederck's Protestant Bohemian subjects were forced to convert to Catholicism or suffer crushing physical, social and economic persecution. Although Fredrick and Elizabeth were by then in The Hague, a Protestant army, led by Ernst von Mansfeld and Christian of Brunswick, attempted to recover from the Hapsburgs a portion of Northwestern Germany; Mansfeld, however, withdrew from this campaign, leaving Christian to be defeated at the hands of Count Tilly at Stadtlohn. His hopes for regaining his fortunes gone, Frederick signed what was to be a short-lived armistice with Ferdinand. Indeed it was truly a time of blight and defeat. The only glimmer of hope for the future was in the likelihood that the armistice might restore some of Frederick's former prestige or that Mansfeld, still uncaptured, might again raise an army.

Comenius took Kotter's prophecy and illustration in their manuscript form to The Hague and showed them to Frederick there in 1626. Kotter's text justifies and supports Frederick's position, and because the text and its illustration were written about 1624, they still hold out a dream for Frederick's eventual victory and apotheosis.

The Millennial symbolism in the Kotter illustration echoes hauntingly in The Magic Flute, which was itself created in the midst of enormous change both in Europe an in the immediate Viennese milieu. Was a parallel between the two historical eras evident to the opera's creators? In the Schaffers' illustration of the first scene of the opera we find a detail which suggests that this is indeed the case. The young prince Tamino, wearing a Javanese hunting jacket, flees from a serpent which is pursuing him. He cannot attack the serpent because he had no arrows for his bow. After calling to the gods for help, Tamino faints. Just as the serpent is about to harm him, the Queen of Night's Three Ladies appear and in some unspecified manner kill the serpent with their silver spears. The original libretto of 1791 does not even indicate that the Ladies kill the serpent, although later there is an obvious reference to the fact that the creature is dead. Mozart, however, inserted a triumphant fanfare for the Ladies with his own added text: "Stirb, Ungeheu'r, durch unsre Macht!" ("Die, monster, by our power!") Yet in neither the libretto nor in Mozart's score is there any reference to the following stage direction, usually included in modern editions of the opera: "Sie stossen die Schlange zu drei Stücken entzwei" ("They prod the serpent apart into three pieces"). But three years later, Josef and Peter Schaffer published the color illustrations presumed to be of Schikaneder's production of the opera; the illustration for this scene in Act I shows the serpent clearly cut into three segments.

The date above the illustration is 1623, a significant year in the course of the Thirty Years' War, for in that year Frederick and the Protestant cause were suffering abject defeat in spite of what had appeared to be a propitious beginning in the Elector's political career. Frederick, having married Elizabeth in England in 1613, had returned with her to Heidelberg, Germany, and soon after was elected by the Bohemian Diet to supplant the newly crowned successor to Emperor Rudolph II of Bohemia: the Archduke Ferdinand of Styria. Ferdinand held an extreme Roman Catholic position. In addition, his kingship was based on his Hapsburg lineage under the assumption that Bohemia would be ruled hereditarily by the Hapsburgs. The Bohemian Diet, however, was largely Protestant. They deposed Ferdinand and chose Frederick to be King of Bohemia. In a time when open hostility had already been established, Frederick was faced with growing opposition by the Hapsburg empire and its Catholic allies. At the outset of what was to become the devastating Thirty Years' War, Frederick's forces, attempting to put down a rebellion of Bohemian Catholics, were defeated at the White Mountain in November of 1620.

Frederick and Elizabeth left Prague and made their way-not to the Palatinate, which by then had been invaded by armies of the Spanish Hapsburgs, but to the Netherlands, where Calvinist Protestantism was firmly established and Frederick, a Calvinist, was welcome. Elizabeth, too, was received in great favor, for there were historical ties between England and the House of Orange. In 1623, however, the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand stripped Frederick of his title of Elector, a drastic step considered illegal by most of the other Electors, since the electorate was bestowed for life. Frederck's Protestant Bohemian subjects were forced to convert to Catholicism or suffer crushing physical, social and economic persecution. Although Fredrick and Elizabeth were by then in The Hague, a Protestant army, led by Ernst von Mansfeld and Christian of Brunswick, attempted to recover from the Hapsburgs a portion of Northwestern Germany; Mansfeld, however, withdrew from this campaign, leaving Christian to be defeated at the hands of Count Tilly at Stadtlohn. His hopes for regaining his fortunes gone, Frederick signed what was to be a short-lived armistice with Ferdinand. Indeed it was truly a time of blight and defeat. The only glimmer of hope for the future was in the likelihood that the armistice might restore some of Frederick's former prestige or that Mansfeld, still uncaptured, might again raise an army.

Comenius took Kotter's prophecy and illustration in their manuscript form to The Hague and showed them to Frederick there in 1626. Kotter's text justifies and supports Frederick's position, and because the text and its illustration were written about 1624, they still hold out a dream for Frederick's eventual victory and apotheosis.

The Millennial symbolism in the Kotter illustration echoes hauntingly in The Magic Flute, which was itself created in the midst of enormous change both in Europe an in the immediate Viennese milieu. Was a parallel between the two historical eras evident to the opera's creators? In the Schaffers' illustration of the first scene of the opera we find a detail which suggests that this is indeed the case. The young prince Tamino, wearing a Javanese hunting jacket, flees from a serpent which is pursuing him. He cannot attack the serpent because he had no arrows for his bow. After calling to the gods for help, Tamino faints. Just as the serpent is about to harm him, the Queen of Night's Three Ladies appear and in some unspecified manner kill the serpent with their silver spears. The original libretto of 1791 does not even indicate that the Ladies kill the serpent, although later there is an obvious reference to the fact that the creature is dead. Mozart, however, inserted a triumphant fanfare for the Ladies with his own added text: "Stirb, Ungeheu'r, durch unsre Macht!" ("Die, monster, by our power!") Yet in neither the libretto nor in Mozart's score is there any reference to the following stage direction, usually included in modern editions of the opera: "Sie stossen die Schlange zu drei Stücken entzwei" ("They prod the serpent apart into three pieces"). But three years later, Josef and Peter Schaffer published the color illustrations presumed to be of Schikaneder's production of the opera; the illustration for this scene in Act I shows the serpent clearly cut into three segments.

If the illustration is a reliable depiction of Schikaneder's production, as Chailley believes, why was such a strange bit of stage business included? Following the interpretation of the Kotter text, Tamino is the prince from the East, i.e., a young and uninitiated royal personage who is in the future to become a Magus, a wise man and ruler. The serpent, which the Three Ladies slay, is Hypocrisy. This interpretation of the scene, parallel to Kotter's prophetic vision, give the Three Ladies great ethical importance, a trait that they display also when they punish Papageno for lying.

However, in another vein, the serpent has for centuries connoted wisdom, wholeness or health (seen in ancient associations with Moses in the wilderness and the Greek healer Asclepius). In a sense, the serpent's attacking Tamino suggests that this ancient symbol is forced upon him. Underlying the symbol of the serpent is a sense of craftiness and deception. Is this symbol of an old mode of wisdom rejected precisely because it is ancient and implies arcane knowledge, and is thus unfit for the Enlightenment era? The Ladies not only kill the serpent but destroy its wholeness by prodding it apart. The tripartite separation of the snake is a point of many commentaries on this scene, because a slicing by each of the Ladies would result in four, not three segments. A four-part segmentation would form a clear parallel to Kotter's segmented serpent in the sky, yet the Schaffers chose to represent only a three-part division of the creature. The three segments of the serpent may have been intended as a gesture to the Masonic number three and thus intentionally to prefigure the set with the three Temples of Sarastro's realm. The ancient wisdom or wholeness or health, in the form broken by the Ladies (whatever circumstance or individual or group they represent) must be gained anew for the present age, by experience, through the prince's successful endurance of the trials. When Tamino does finally attain this new wisdom, the unity and healing power of that wisdom will then bring in the New Age. This interpretation of the serpent symbolism points away from the traditional occult or mystical world, not toward it: the serpent is never brought back into the plot, but rather the plot conforms to the then modern Enlightenment humanistic view of man's own self-reliance and ability to work out his own destiny by virtue of his innate reason and goodness, in man-made institutions (the Temples) and in dialogue not with stars and prophetic vision but with other humans and through his own perseverance.

Francis Yates' interpretation of Kotter's dismembered serpent also suggests parallels to The Magic Flute. She pointed to the serpent as the constellation Serpentarius, in which could be read a prophecy of great events, that is Frederick's success. When these prophecies failed, in Kotter's view, the prophecy-generating serpent was punished. What might the parallel to Frederick's failed movement be, if such it is that inspired the sliced serpent? If the Shaffers' illustration reflects the 1791 Vienna production, that is, at the end of the first year of the reign of Leopold II, it is possible that the allusion is to the passing of the Josephine era and its season of social and political reforms. But if indeed the illustrations reflect not Schikaneder's 1791 production (or the 1792 Prague version of it) but rather the 1793 Brno production they would have been created only one year after the completely unexpected death of Leopold II, and, incidentally, exactly 170 years after the date on Kotter's illustration. Succeeding Leopold as Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II's general conservatism must necessarily have been exacerbated by his concern for controlling his populace at a time when France, for example, was still in the bloody throes of a revolution that branded all aristocracy anathema. Francis II is the Emperor under whose reign Freemasonry was to be absolutely banned in Austria and under whom Poland was to be totally absorbed by Austria and her neighbors Russia and Prussia. What may have been perceived to have failed in the first years of Francis' reign was the relatively steady-handed if cautious governance of Leopold, or the era of reform begun by Joseph II. Progress toward a better land, in Sarastro's words, seemed possible in the 1780's, but this optimistic vision was being eroded internally by Francis' increasingly strict measures control. On a broader scale, the execution Louis XVI in January of 1793 signaled the end of the more moderate phase of France's revolution, in which some compromise might have been reached between a regent descended from a royal bloodline and an elected body representing the populace. The eyes of all Europe were upon the French situation. There is hardly room for doubting that Louis' death would have had a tremendous impact in every quarter. Whatever reforms might have come about in a moderation of the monarchic system were precluded by this event.

However, in another vein, the serpent has for centuries connoted wisdom, wholeness or health (seen in ancient associations with Moses in the wilderness and the Greek healer Asclepius). In a sense, the serpent's attacking Tamino suggests that this ancient symbol is forced upon him. Underlying the symbol of the serpent is a sense of craftiness and deception. Is this symbol of an old mode of wisdom rejected precisely because it is ancient and implies arcane knowledge, and is thus unfit for the Enlightenment era? The Ladies not only kill the serpent but destroy its wholeness by prodding it apart. The tripartite separation of the snake is a point of many commentaries on this scene, because a slicing by each of the Ladies would result in four, not three segments. A four-part segmentation would form a clear parallel to Kotter's segmented serpent in the sky, yet the Schaffers chose to represent only a three-part division of the creature. The three segments of the serpent may have been intended as a gesture to the Masonic number three and thus intentionally to prefigure the set with the three Temples of Sarastro's realm. The ancient wisdom or wholeness or health, in the form broken by the Ladies (whatever circumstance or individual or group they represent) must be gained anew for the present age, by experience, through the prince's successful endurance of the trials. When Tamino does finally attain this new wisdom, the unity and healing power of that wisdom will then bring in the New Age. This interpretation of the serpent symbolism points away from the traditional occult or mystical world, not toward it: the serpent is never brought back into the plot, but rather the plot conforms to the then modern Enlightenment humanistic view of man's own self-reliance and ability to work out his own destiny by virtue of his innate reason and goodness, in man-made institutions (the Temples) and in dialogue not with stars and prophetic vision but with other humans and through his own perseverance.

Francis Yates' interpretation of Kotter's dismembered serpent also suggests parallels to The Magic Flute. She pointed to the serpent as the constellation Serpentarius, in which could be read a prophecy of great events, that is Frederick's success. When these prophecies failed, in Kotter's view, the prophecy-generating serpent was punished. What might the parallel to Frederick's failed movement be, if such it is that inspired the sliced serpent? If the Shaffers' illustration reflects the 1791 Vienna production, that is, at the end of the first year of the reign of Leopold II, it is possible that the allusion is to the passing of the Josephine era and its season of social and political reforms. But if indeed the illustrations reflect not Schikaneder's 1791 production (or the 1792 Prague version of it) but rather the 1793 Brno production they would have been created only one year after the completely unexpected death of Leopold II, and, incidentally, exactly 170 years after the date on Kotter's illustration. Succeeding Leopold as Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II's general conservatism must necessarily have been exacerbated by his concern for controlling his populace at a time when France, for example, was still in the bloody throes of a revolution that branded all aristocracy anathema. Francis II is the Emperor under whose reign Freemasonry was to be absolutely banned in Austria and under whom Poland was to be totally absorbed by Austria and her neighbors Russia and Prussia. What may have been perceived to have failed in the first years of Francis' reign was the relatively steady-handed if cautious governance of Leopold, or the era of reform begun by Joseph II. Progress toward a better land, in Sarastro's words, seemed possible in the 1780's, but this optimistic vision was being eroded internally by Francis' increasingly strict measures control. On a broader scale, the execution Louis XVI in January of 1793 signaled the end of the more moderate phase of France's revolution, in which some compromise might have been reached between a regent descended from a royal bloodline and an elected body representing the populace. The eyes of all Europe were upon the French situation. There is hardly room for doubting that Louis' death would have had a tremendous impact in every quarter. Whatever reforms might have come about in a moderation of the monarchic system were precluded by this event.

The segmented serpent, interpreted by Yates as the constellation Serpentarius, may also have another meaning, a specific one directly associated with the strife between the Bohemians and the Hapsburgs. The Battle of the White Mountain in 1620 was for the defeated Bohemians the beginning of a long era of Hapsburg oppression. Bohemian bitterness against the house of Hapsburg was summarized by a contemporary of Comenius, Mikulás Drabík, when he referred to the Hapsburgs as "the Austrian viper." With this interpretation of the serpent, then, Kotter's displaying the serpent in four segments in his prophetic illustration would have signified some kind of division of the Hapsburgs, possibly by the election of Frederick by the Protestant faction of the Bohemian Diet. If the Schaffers knew of Drabík's comment, their depiction of the sliced serpent in The Magic Flute illustration for a Bohemian publication would have had a clear revolutionary meaning.

Such speculation abut a symbolic meaning for the cut-up serpent in the Schaffers' illustration derives, of course, from the hypothesis that not only Kotter's vision in Lux in Tenebris was known to the circles around The Magic Flute, but also the original meaning and implications of the vision were understood in the late eighteenth century. Here again there is no direct data by which to confirm that Lux in Tenebris was specifically a source of the (possibly spurious) detail in the opera. However, it is a fact that Lux in Tenebris is named in the Zettelkatalog assembled under Gottfried van Swieten's directorship in 1780-81. Here is proof of accessibility of the Kotter illustration to the circle of those associated with the opera, for the library collection in the decade of the 1780's was open to all those recognized as serious readers or students. Yet such a work was apparently somewhat out of the mainstream of writing from the Rosicrucian era. it is not one of the sources, for example, for the original story or the alchemical treatment of the heirosgamos. As a kind of second-level work, it would not have been likely to attract the attention of the casual reader, but would likely have emerged through the auspices of someone who not only knew the collection intimately but had been aware of its content by reference or by actually have read it, and who drew the parallel to the contemporary situation in the Bohemian region. The choices for candidates who fulfill these criteria are few. The known Rosicrucian aristocrats, Thun, Gemmingen, Sinzendorf, and Dietrichstein spring to mind, although there were undoubtedly others. More to the point, Prince Dietrichstein was closely associated with Gottfried van Swieten in the Society of Cavaliers, in which Mozart was active in the years 1788-1790. Circumstantially, the involvement of van Swieten seems probable in making available access to Lux in Tenebris and perhaps even in sharing information of its content and meaning with Mozart and others in The Magic Flute's environment.

Such speculation abut a symbolic meaning for the cut-up serpent in the Schaffers' illustration derives, of course, from the hypothesis that not only Kotter's vision in Lux in Tenebris was known to the circles around The Magic Flute, but also the original meaning and implications of the vision were understood in the late eighteenth century. Here again there is no direct data by which to confirm that Lux in Tenebris was specifically a source of the (possibly spurious) detail in the opera. However, it is a fact that Lux in Tenebris is named in the Zettelkatalog assembled under Gottfried van Swieten's directorship in 1780-81. Here is proof of accessibility of the Kotter illustration to the circle of those associated with the opera, for the library collection in the decade of the 1780's was open to all those recognized as serious readers or students. Yet such a work was apparently somewhat out of the mainstream of writing from the Rosicrucian era. it is not one of the sources, for example, for the original story or the alchemical treatment of the heirosgamos. As a kind of second-level work, it would not have been likely to attract the attention of the casual reader, but would likely have emerged through the auspices of someone who not only knew the collection intimately but had been aware of its content by reference or by actually have read it, and who drew the parallel to the contemporary situation in the Bohemian region. The choices for candidates who fulfill these criteria are few. The known Rosicrucian aristocrats, Thun, Gemmingen, Sinzendorf, and Dietrichstein spring to mind, although there were undoubtedly others. More to the point, Prince Dietrichstein was closely associated with Gottfried van Swieten in the Society of Cavaliers, in which Mozart was active in the years 1788-1790. Circumstantially, the involvement of van Swieten seems probable in making available access to Lux in Tenebris and perhaps even in sharing information of its content and meaning with Mozart and others in The Magic Flute's environment.

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.