- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

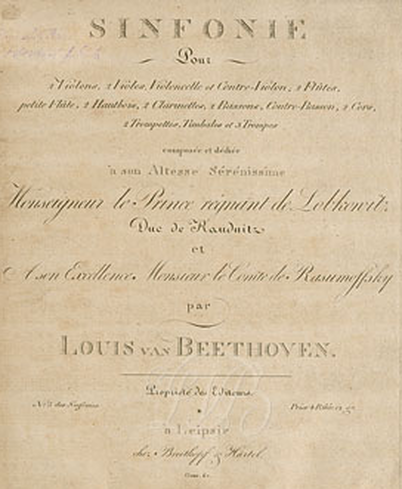

BEETHOVEN: SYMPHONY NO. 5 in C-MINOR, OP.67

by Judith Eckelmeyer

(GRACE WOODS MUSIC SESSION NOVEMBER 21, 2022)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) arrived in Vienna in 1792 to make his home and career there. He had “inherited” the common language of the “Viennese School”—Mozart and Haydn—when he began composing in his hometown, Bonn. It was not surprising, then, that he continued the style when he continued composing in that great music capital, albeit with supplemental training in counterpoint. At first he worked with Joseph Haydn, the most famous composer in the world at the time, and later, after a rift with Haydn, with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. By the turn of the century, he had achieved support of aristocratic admirers and compositional success primarily through his piano sonatas and chamber music.

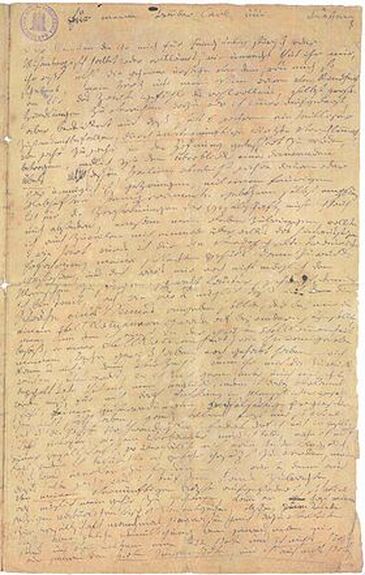

Just after 1800, he became aware of increasing problems with his hearing. He was 31. The impact on his life was profound, and without question influenced his compositions. He began to reckon with it in writing with a famous letter, the “Heiligenstadt Testament”, to his brother in 1802, describing his despair at not being able to hear sounds of nature in his walks in this suburb of Vienna, his isolation from society, his increasing loneliness; only his dedication to “his art” and his determination to continue composing prevented him from ending his life. Later he would tell his friend, secretary and biographer Anton Schindler, that he thought of the famous 4-note rhythm so prominent in the fifth symphony as “fate knocking at the door”. Beethoven’s struggle with his deafness affected his work from the third symphony on, and the ominous rhythm is evident in numerous works of the middle and late periods of his composition.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is arguably the best-known classical work in the western world. However, recognizing the subtleties in the work, informed by an understanding of Beethoven’s personal struggle at the time he wrote it, we might hear it in a very different way from our experience as casual listeners. I believe it is an autobiographical statement, a kind of translation of the “Heiligenstadt Testament” into untexted sound, setting it at the very edge of “program” music

Before hearing the work again, we should note several things. First, the “normal” structure of two of the movements of the symphony in Beethoven’s time, and then some features that Beethoven introduced (some for the first time) in this symphony.

Before hearing the work again, we should note several things. First, the “normal” structure of two of the movements of the symphony in Beethoven’s time, and then some features that Beethoven introduced (some for the first time) in this symphony.

Structure:

First Movement: Called erroneously “first movement or sonata-allegro form”, it is none of the above! It doesn’t belong just to the sonata, it’s not always in an allegro tempo, nor relegated only to the first movement, and it’s not a pre-cast form into which music is poured but rather a process for treating musical materials. There are three “events”: an exposition of thematic material in 2 parts, first in the home key then in a contrasting key; a development of the theme(s) in any number of ways and varied keys, ending in a harmonic “door” back to the home key, where the original themes are presented again, ending in the original key.

Dance Movement (minuet or scherzo, often the 3rd movement): There are really 2 dances, the primary minuet or scherzo followed by a “trio”, a lighter dance in a related key (originally played by fewer instruments). Both dances are structured in the same way: Part A, establishing a key and usually moving out of the key, then repeated; Part B, starting in Part A’s new key and returning to the original key, often with at least some of the theme from Part A, and then repeated. After the first dance, the second dance is presented, in the same organization as the first dance. Then, the entire first dance is given again, as written, but usually performed without the repeats of the 2 sections.

First Movement: Called erroneously “first movement or sonata-allegro form”, it is none of the above! It doesn’t belong just to the sonata, it’s not always in an allegro tempo, nor relegated only to the first movement, and it’s not a pre-cast form into which music is poured but rather a process for treating musical materials. There are three “events”: an exposition of thematic material in 2 parts, first in the home key then in a contrasting key; a development of the theme(s) in any number of ways and varied keys, ending in a harmonic “door” back to the home key, where the original themes are presented again, ending in the original key.

Dance Movement (minuet or scherzo, often the 3rd movement): There are really 2 dances, the primary minuet or scherzo followed by a “trio”, a lighter dance in a related key (originally played by fewer instruments). Both dances are structured in the same way: Part A, establishing a key and usually moving out of the key, then repeated; Part B, starting in Part A’s new key and returning to the original key, often with at least some of the theme from Part A, and then repeated. After the first dance, the second dance is presented, in the same organization as the first dance. Then, the entire first dance is given again, as written, but usually performed without the repeats of the 2 sections.

New Features:

- The entire work is permeated with the 4-note rhythmic “theme”, through which one can hear changes in musical material that suggest changes in the composer’s manner of dealing with his “fate”.

- After the Trio, the return of the first dance in the Scherzo movement is quite altered in content and mood, not an exact repeat of the it.

- Beethoven connects the third movement Scherzo via a kind of bridge to the final movement with no pause between the movements.

- There is a reminder, in the middle of the last movement, of the music of the third movement.

- Beethoven extends the end of the last movement with an extraordinarily long coda, ending not in the home key of C-minor but in C MAJOR.

- Beethoven introduces the highest and the lowest wind instruments into the last movement—trombones and piccolos. Trombones had been used in operas for a long time. Piccolos were largely decorative or martial instruments.

Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor

Wiener Philharmoniker | Leonard Bernstein, conductor

Wiener Philharmoniker | Leonard Bernstein, conductor

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.