- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

MADRIGAL

Facts and Fun About Madrigals

By Judith Eckelmeyer

What’s a madrigal, you ask?

Simply put, it’s a genre (type) of non-religious (secular) unaccompanied vocal music that became extremely popular in Europe in the 16th century, and continued to be written in most of the first half of the 17th century especially in Italy and England. In fact, the madrigal was so popular that composers from most of Europe wrote in the genre. However, although the Italians made so many innovations in the Renaissance (ca. 1450-1600), northern European composers “invented” the madrigal in Italy around 1530, while the Italians were primarily writing other secular types such as the frottola at that time. The madrigal superseded the frottola in attracting the attention of major composers; it certainly provided them with opportunities for more musical ingenuity and experimentation, and they were clearly eager to write madrigals in great numbers.

In writing madrigals, composers engaged in solving the problem of setting a secular poem—a sonnet or some other form—to music for a small group of singers, usually from four to six or more. The poems were in Italian and always sung in Italian. At the earliest stage of madrigal writing the texts consisted of innocent poetry about love and wit, sung by four voices; but increasingly through the century composers chose highly sensual poems with many erotic images and allusions to sex. With the change in the focus of the poetry came increasing sophistication of the music, and composers employed from five to even eight singers and putting their attention on expression, depicting effects or events in the text, and eventually declaiming the text in a dramatic fashion. A bit later in this introduction to the madrigal there will be a general overview of who was writing when, and where, to help clarify how the madrigal developed over the century.

Who performed madrigals?

Madrigals were written as social entertainment for the middle-class and aristocracy who, in the Renaissance, were expected to be able to read music and perform, either vocally or on an instrument—optimally, both. Compartmentalization of musical skill to only professional musicians was a foreign concept in that era. Rather, those who wished to be considered “civilized” individuals, or “gentle people”, were expected to be broadly educated and participate in the arts as patrons or performers. Performing music was for the performers themselves and their immediate circle rather than for the public. A merchant’s family and dinner guests, for instance, might entertain themselves after dinner in their home by singing madrigals indoors around the dinner table. The aristocratic class might enjoy performing madrigals in an outdoor setting—a garden or private park—for their own diversion. Or they might have their household musicians (part of the usual staff of the nobility) entertain them and guests at a feast or celebration.

Madrigals were written as social entertainment for the middle-class and aristocracy who, in the Renaissance, were expected to be able to read music and perform, either vocally or on an instrument—optimally, both. Compartmentalization of musical skill to only professional musicians was a foreign concept in that era. Rather, those who wished to be considered “civilized” individuals, or “gentle people”, were expected to be broadly educated and participate in the arts as patrons or performers. Performing music was for the performers themselves and their immediate circle rather than for the public. A merchant’s family and dinner guests, for instance, might entertain themselves after dinner in their home by singing madrigals indoors around the dinner table. The aristocratic class might enjoy performing madrigals in an outdoor setting—a garden or private park—for their own diversion. Or they might have their household musicians (part of the usual staff of the nobility) entertain them and guests at a feast or celebration.

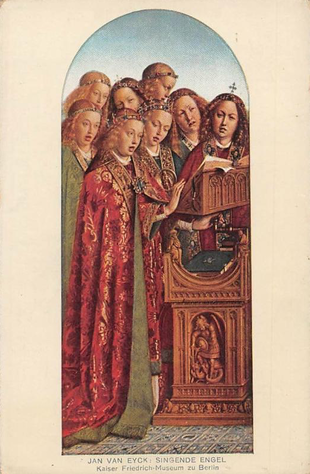

Madrigal singing is different from the kind of singing by a trained choir that one would hear in church. While both kinds of music had multiple parts that created harmony, in a church choir there would be several people singing together in Latin on each part, creating a moderate-sized ensemble. In madrigal singing, there is only one person singing each line of music by him- or herself in Italian, the everyday language of the people; typically there is no instrument playing the same lines along with the voices, and no independent instrumental accompaniment. Only men sang in church choirs, but women as well as men participated in singing madrigals, taking the uppermost parts of course; often some of the high middle voices, which we might call “alto”, were sung by male countertenors.

Today as then, the individual singers of madrigals have to blend and integrate their part with the other singers’ parts to make the whole fabric of the music sound well. This “one-on-a-part” unaccompanied singing is both fun and challenging; it’s a fine example of the adage “the chain is only as strong as its weakest link”. It is also a very intimate kind of performing, requiring subtle communication among the singers to establish tempo, dynamics, starting and stopping, and creating emotional sense in the music.

Today as then, the individual singers of madrigals have to blend and integrate their part with the other singers’ parts to make the whole fabric of the music sound well. This “one-on-a-part” unaccompanied singing is both fun and challenging; it’s a fine example of the adage “the chain is only as strong as its weakest link”. It is also a very intimate kind of performing, requiring subtle communication among the singers to establish tempo, dynamics, starting and stopping, and creating emotional sense in the music.

Why do madrigals vary in style so much?

Musical composition did not remain static throughout the Renaissance because composers were always trying new ways of writing their music. Some of the changes came through the influence of composers from different regions who brought new methods of writing; other changes came about because of developments external to music itself. For instance, the educated classes were deeply involved in learning the ancient Greeks’ and Romans’ theories of poetry and rhetoric. Differences in these theories spurred new ideas on how to treat poetry in music. As I’ll show, by the end of the 16th century there were very major changes in madrigal-writing that resulted from these studies of the ancient poets and theorists.

Musical composition did not remain static throughout the Renaissance because composers were always trying new ways of writing their music. Some of the changes came through the influence of composers from different regions who brought new methods of writing; other changes came about because of developments external to music itself. For instance, the educated classes were deeply involved in learning the ancient Greeks’ and Romans’ theories of poetry and rhetoric. Differences in these theories spurred new ideas on how to treat poetry in music. As I’ll show, by the end of the 16th century there were very major changes in madrigal-writing that resulted from these studies of the ancient poets and theorists.

When did these different styles occur, and who wrote them?

Northern madrigal writers living in Italy started the ball rolling around 1530, with relatively simple four-part settings of witty Italian texts or poems about carefree aspects of love. These composers were from today’s northern France or southern Belgium; Philippe Verdelot and Jacques Arcadelt were the two leading early composers of madrigals. They introduced some of their sacred motet style into the secular compositions, making the pieces somewhat contrapuntal and imitative at times, or simply a melody supported by chords (homophonic) at others.

Northern madrigal writers living in Italy started the ball rolling around 1530, with relatively simple four-part settings of witty Italian texts or poems about carefree aspects of love. These composers were from today’s northern France or southern Belgium; Philippe Verdelot and Jacques Arcadelt were the two leading early composers of madrigals. They introduced some of their sacred motet style into the secular compositions, making the pieces somewhat contrapuntal and imitative at times, or simply a melody supported by chords (homophonic) at others.

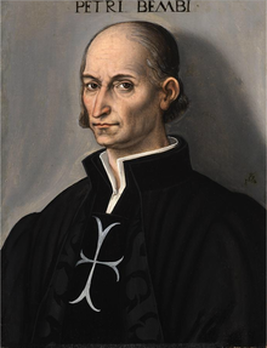

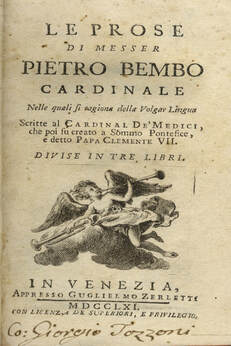

In 1525 the humanist poet and scholar Pietro Bembo published Prose della volgar lingua (Prose on Vernacular Eloquence), a long dialogue discussing poetic categories, the importance of the sounds of words, and matters of poetic structure; equally important, he also held up the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarcho—Petrarch—as the literary ideal.

Composers such as the northerner Adrian Willaert and the Italian Gioseffo Zarlino (Willaert’s student) sought to reflect these text differences in their music by using contrasting types of harmonies and different kinds of melodic lines. Many of these madrigals had not just four but five or six lines of music. These characteristics would endure in Italian madrigals through the rest of the century.

By mid-century, another northerner—Cipriano de Rore—began intensifying the music to suit increasingly vivid texts by introducing more dissonant and out-of-scale (chromatic) notes, more varied rhythms, and changes in the number of voices singing at any one time.

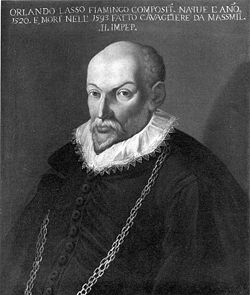

His practices influenced the extension of the musical style of the slightly later northerners Orlando di Lasso, Philippe de Monte, and Giaches de Wert. Lasso and Wert began writing madrigals in Italy but then went to courts in northern cities, spreading the fashion for madrigal-writing abroad.

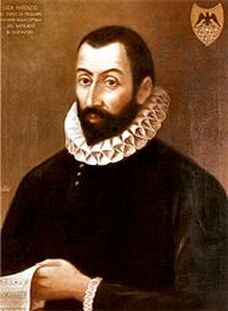

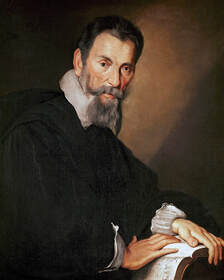

Finally, Italian composers of madrigals had their heyday. Luca Marenzio, Carlo Gesualdo, prince of Venosa, and Claudio Monteverdi are the undisputed masters of the late 16th-century madrigal. Up to that time madrigal composers had gradually expanded the list of poets whose works they chose to set to music; these late 16th-century Italians selected from not only Petrarch but also the most modern writers of their day such as Torquato Tasso and Giovanni Battista Guarini. The variety of techniques they used to illustrate these poets’ often highly emotional texts in music are called “madrigalisms”—devices that interpret what the text says. The ranges of the voices expanded, especially in Gesualdo’s madrigals, where extremes of high and low evoke tension and passion, key elements in his own dramatic and sordid life. Dissonances increased to almost painful levels, again especially in Gesualdo’s works, where they appear on passionate words such as pain, sorrow, death, anguish, cruelty, and such. Tortured chromaticism contrasted with simple harmonies for effect. Rhythms varied enormously to reflect varieties of action in the text.

Of these three Italians, Monteverdi (1567-1643) takes the prize for moving the madrigal forward in an entirely new direction. He wrote a total of nine collections, or books, of these pieces. By the fifth book he showed he had begun to explore a totally new style that we think of as no longer “Renaissance” but rather “Baroque”. These are essentially accompanied songs rather than unaccompanied ensemble works, and make up the bulk of the genre he composed in the first half of the 17th century. They differ substantially in style from the Renaissance madrigals by following the natural rhythms of the Italian language, as the poem would have been recited, rather than subordinating the language to musical procedures and structured rhythms imposed on the text. These new-style madrigals are masterpieces of the expression of text, using all the known rhetorical devices to assure the text’s impact on the listener. Their style is actually that of the emerging new genre, opera.

Claudio Monteverdi, madrigali e canzoni per due e tre voci, Libro IX (1651)

Complesso vocale "Polifonia" Angelo Ephrikian, direttore

Gastone Sarti, Baritono | Rodolfo Farolfi, GiorgioMaelli, tenore | Rascida Agosti, contralto | Armando Burattin, viola da gamba | Mariella Sorelli, clavicembalo

Complesso vocale "Polifonia" Angelo Ephrikian, direttore

Gastone Sarti, Baritono | Rodolfo Farolfi, GiorgioMaelli, tenore | Rascida Agosti, contralto | Armando Burattin, viola da gamba | Mariella Sorelli, clavicembalo

Were there any women composing madrigals?

Indeed there were! The best known is Maddelena Casulana (1544-1590s), whose music was actually published (a rarity for women in that time) and who was known as a professional composer and singer. She wrote three books of madrigals that fully exemplify the style of the time.

Indeed there were! The best known is Maddelena Casulana (1544-1590s), whose music was actually published (a rarity for women in that time) and who was known as a professional composer and singer. She wrote three books of madrigals that fully exemplify the style of the time.

Maddelena Casulana

"Vagh' amorosi augelli" | "O notte o ciel o mar" | "Morir non può il mio core"

Ensemble Laus Concentus: Lavinia Bertotti, soprano (1) Silvia Piccollo, soprano (2)

Massimo Lonardi, liuto e arciliuto Maurizio Piantelli, liuto e tiorba Maurizio Less, viola da gamba

"Vagh' amorosi augelli" | "O notte o ciel o mar" | "Morir non può il mio core"

Ensemble Laus Concentus: Lavinia Bertotti, soprano (1) Silvia Piccollo, soprano (2)

Massimo Lonardi, liuto e arciliuto Maurizio Piantelli, liuto e tiorba Maurizio Less, viola da gamba

There were also renowned women singers who performed the secular works available at the time. Some of these women, like Lucrezia and Isabella Bendidio in Ferrara, were actually professional singers, rather than amateur performers of the noble class. A group of trained singers, also in Ferrara at the court of Duke Alfonso d’Este, became so famous that other aristocrats in Mantua and Florence decided to try to match them with their own ensembles.

For those of us who thought only men wrote music before the 20th century and never realized there were famous women performers in the Renaissance, it may come as a shock that we actually know the names of the Ferrara concerto delle donne (ensemble of women): Laura Peverara, Anna Guarini, and Livia D’Arco.

What are English madrigals?

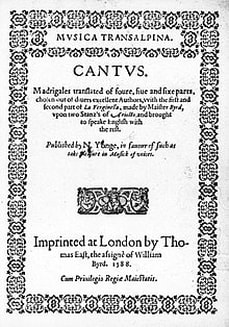

By the 1560s, the English aristocracy and middle-class were beginning to sing and enjoy Italian madrigals in the same kinds of settings as in Italy. A couple of decades later Nicholas Yonge translated some Italian madrigals into English and published them as Musica transalpine (Music across the Alps).

By the 1560s, the English aristocracy and middle-class were beginning to sing and enjoy Italian madrigals in the same kinds of settings as in Italy. A couple of decades later Nicholas Yonge translated some Italian madrigals into English and published them as Musica transalpine (Music across the Alps).

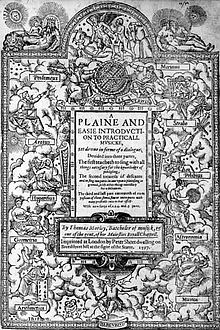

This collection spurred English composers like Thomas Morley, Thomas Weelkes and John Wilbye to write their own madrigals with English texts.

A bit later, more than two-dozen English composers jumped on this bandwagon. Particularly noteworthy is John Dowland, whose style is famously serious, treating melancholy texts with exceptionally beautiful music. The title of one of his instrumental works is “Semper Dowland, semper dolens” (always Dowland, always doleful), perhaps facetiously referring to the fact that he was varying his own song “Flow my tears”, but also acknowledging his penchant for sorrowful texts and writing music for them.

English composers expanded their secular writing to include adaptations of two additional Italian genres, the canzonetta and balletto, which they called canzonets and balletts. The balletts were very merry and dancelike in their rhythm, and used the Fa-la-la refrain, which we know from the familiar carol, “Deck the halls with boughs of holly…”—a very fine example of a balletto. Often the English balletts and canzonets are lumped under the category of English madrigal.

|

Giles Farnaby -Canzonets to Four Voices: No. 20,

"Construe My Meaning" The King's Singers |

Thomas Morley - Balletts to Five Voyces, Book 1: No. 2,

"Shoot, False Love, I Care Not" The King's Singers |

Were there madrigals in other European countries?

Not generally as such (although there are exceptions), but secular vocal music certainly flourished in France, Germany, and Spain in the 16th century. The French called their secular songs “chansons” (never madrigals!), and there were many composers writing them. Premiere among the early 16th-century polyphonic chanson composers was Josquin des Pres. After Josquin, in the 1530s and 1540s, a new generation of composers mostly eliminated imitative polyphony and simplified the style of the genre.

Not generally as such (although there are exceptions), but secular vocal music certainly flourished in France, Germany, and Spain in the 16th century. The French called their secular songs “chansons” (never madrigals!), and there were many composers writing them. Premiere among the early 16th-century polyphonic chanson composers was Josquin des Pres. After Josquin, in the 1530s and 1540s, a new generation of composers mostly eliminated imitative polyphony and simplified the style of the genre.

Chansons by Pierre Certon, Jacques Arcadelt, Pierrot Passeraux, Claudin de Sermisy and Clément Janequin appeared in collections published by Pierre Attaignant in Paris, and the style became known as the Parisian chansons.

Pierre Certon "Amour a tort"

Harmonia Mundi

Harmonia Mundi

|

Claudin de Sermisy "Au joly boys"

|

Clément Janequin "Le chant des oiseaux"

Unknown performers |

The subject matter of the Parisian chansons varied greatly, from courtly to comic and witty. In another type, Clément Janequin imitated natural sounds of birds, battle scenes, hunting, and pastoral scenes. One amazing work is “La Guerre” (The War), with trumpet signals, horses’ hooves, battle cries, noise of fighting, and shouts of victory along with narration.

Clément Janequin "La Guerre"

King's Singers

King's Singers

Another French secular vocal genre arising in the 1550s was musique mesurée, in which the rhythms were based on ancient Greek poetic rhythms; Claude le Jeune was the prominent composer. Finally, in the last two decades of the century, the air de cour, or court song, became popular as a song with accompaniment.

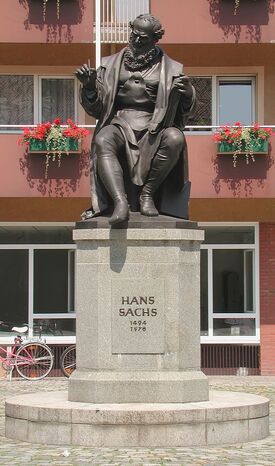

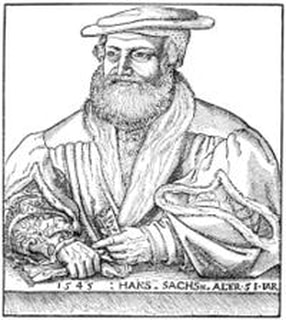

In Germany, several trends ran through the century. The oldest were the songs created by the Meistersinger (Mastersingers), a guild of amateur poet/composers such as the shoemaker Hans Sachs, who had to conform to specific rules to write text and music and sing their songs in public contests.

A more relaxed genre was the Lied, or song, which was usually polyphonic and very similar to the chansons of the French composers of the first part of the 16th century. A number of German composers wrote secular Lieder, especially Hans Leo Hassler, in Augsburg, and Orlando di Lasso (aka Orlande de Lassus), at the ducal court of Munich in Bavaria. Lasso composed not only German Lieder but Italian madrigals and French chansons as well—tons of them, enough to keep singers busy for decades!

Spanish secular vocal music was either a romance, a folk-like adventure story or legend, or a villançico—anything that wasn’t a romance! Usually the villancico was dramatic, hot-blooded, and lusty, with occasional emotional outbursts, and had a refrain between stanzas. Juan del Encina was the leading composer of this genre.

Madrigals in the 20th century?

Yes indeed! The genre has seen a revival in works by Alfred Schnittke, Joaquín Rodrigo, Emma Lou Diemer, Judith Lang Zaimont, and countless others too numerous to name. Seek them out and enjoy today’s madrigals!

Yes indeed! The genre has seen a revival in works by Alfred Schnittke, Joaquín Rodrigo, Emma Lou Diemer, Judith Lang Zaimont, and countless others too numerous to name. Seek them out and enjoy today’s madrigals!

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.