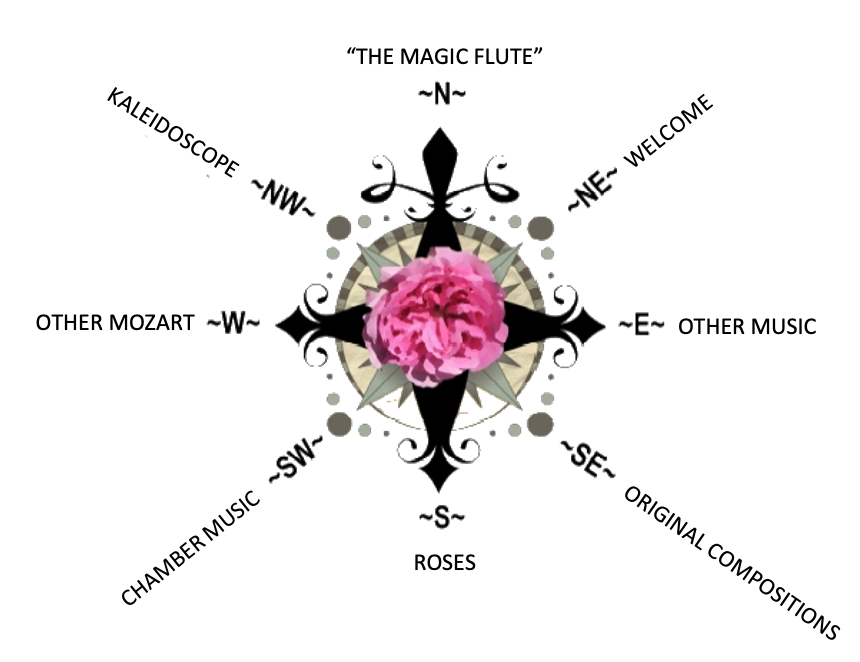

- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

MOZART'S "REQUIEM" AND FREEMASONRY

A Preliminary Inquiry into Masonic Symbolism and Meaning in K. 626

2017

Background

Mozart’s well-known Requiem of 1791 begins in and works around the key of D minor, associated in his music with ominous moods and dark supernatural forces. Nevertheless, it contains a variety of styles: passages of contrapuntal intricacy that Mozart learned from Bach’s and Handel’s music; utterly moving homophony in the “humanistic” style; and gracious lyrical melodies. The work is scored for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists, mixed chorus, 2 bassett horns, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, strings, timpani, and organ.

Myths still associated with the genesis and authenticity of the Requiem have been debunked in recent scholarship, especially that of Christoph Wolff in Mozart’s Requiem (1994). It is comforting to know now that neither his rival Salieri nor demonic forces were at play in the creation of the work. No mysterious stranger, but rather an agent with whom Mozart was actually acquainted, brought him the commission from Count Walsegg, who, following his usual practice, intended to pass the music off as his own for a Mass commemorating his late wife.

As he worked on the Requiem from October to early December 1791, Mozart became increasingly ill and was aware that he was failing; according to witnesses, he thought he was composing the work for his own funeral. He did in fact die, of unusual but natural causes, on December 5. He had finished writing out the final fair copy of the vocal and most of the instrumental parts of the Requiem up to the end of the eighth measure of the “Lacrymosa”, the last movement in the funeral Sequence, “Dies irae”. (String and woodwind parts for the Kyrie were written out by his student Franz Joseph Freystädler.) Vocal portions, basso continuo, and parts of some instrumental interludes of the Offertory (“Domine Jesu Christe”) are also in his hand.

According to his widow Constanze, Mozart had given verbal instructions and made sketches and notes for the work’s completion. We now think his student Franz Xaver Süssmayr, ten years Mozart’s junior and of merely conventional talent, hid the tangible information in order to use it to write out the rest of the work and then claim (as he later did) that he had created it all on his own. (Curious that a very gifted composer, Mozart’s friend Joseph Eybler, could manage only a portion of the completion without those notes.) Today scholars think that after measure eight of the “Lacrymosa” movement, the vocal material and a good portion of the accompaniment in the Requiem are just Süssmayr’s working-out of Mozart’s sketches and ideas, and that Süssmayr’s original work consists of the less refined passages of the orchestral accompaniment, interludes, and orchestration. Modern alternative editions to the one attributed to Süssmayr are available today, but these seem to drift farther away from the Mozart original than even Süssmayr did, by often radically changing or by eliminating what the editors think is not authentic to Mozart. Yet in spite of flaws, Süssmayr’s Mozart still survives and continues to be the touchstone for our experience of the Requiem.

The Issue of Authenticity of the Requiem

Many details throughout the Requiem proclaim Mozart’s authorship of the whole. We should remember that although Mozart was only almost 36 when he wrote it, the Requiem represents a mature, evolved style for the composer and shows aspects of transition toward even more sophisticated and subtle techniques. For example, thematic relationships link movements accepted as authentic to Mozart with those supposedly by Süssmayr. Mozart had employed this unifying practice some years earlier (consider the Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466, of 1785) but it was likely not embraced by his student in 1791.

Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466

Detroit Symphony Orchestra | Saleem Ashka, Piano

Detroit Symphony Orchestra | Saleem Ashka, Piano

For instance, note the scale-based opening motif of the “Dies irae”, “Sanctus”, “Confutatis”, and the more subtle “bones” of the opening of the “Agnus Dei”; and listen for the relationship of subject of the “Quam olim Abrahae” fugue to the subject of the “Osanna” fugues and the opening of the “Recordare”. And Mozart inhabits the astonishing enharmonic chromatic modulations in the “Hostias” and “Agnus Dei” (supposedly by Süssmayr), which recall but exceed the ingenious opening of the “Dissonant” string quartet in C, K. 465 (1785).

Mozart's String Quartet in C, K. 465

Quatuor Mosaïques

00:06 - I. Adagio - Allegro

14:08 - II. Andante cantabile

22:18 - III. Menuetto. Allegro

28:36 - IV. Allegro molto

Quatuor Mosaïques

00:06 - I. Adagio - Allegro

14:08 - II. Andante cantabile

22:18 - III. Menuetto. Allegro

28:36 - IV. Allegro molto

Among the most surprising features in the Requiem may be Mozart’s references to other works—other composers’ and his own. His enormous affinity to late Baroque composers was a legacy of his association with Baron Gottfried van Swieten from 1782 onward; van Swieten’s Sunday gatherings made available to Mozart numerous works of the Bach family and Handel. It is not so surprising, then, to find allusions to one of his favorite Baroque models, Handel, for themes of the “Introit” and the “Kyrie” fugue.

Another model, a sinfonia in D-minor by W. F. Bach, is recast in F major in the beautiful “Recordare”. A remarkable confirmation of Mozart’s hand is a moment of self-reference, which occurs in the accompaniment of the “Lacrymosa”: ironically, this music served earlier in 1791 to underlay Papageno’s frantic thoughts of committing suicide in the Finale of The Magic Flute. (Have you remembered that Mozart thought the Requiem was for himself?)

WF Bach's Sinfonia in D minor

Jeune Orchestre Atlantique Conductor & Leader Stéphanie-Marie Degand

Jeune Orchestre Atlantique Conductor & Leader Stéphanie-Marie Degand

Mozart and Freemasonry in Vienna

But Mozart, a Catholic, was also a Freemason. Are there any Masonic elements in Mozart’s Requiem? To answer this in part, we turn to French musicologist Jacques Henry, a Mason, whose work on the subject is not widely known in many circles in this country. In his 1991 book Mozart the Freemason, translated into English by Jack Cain in 2006, Henry explains that the purpose of “Masonic assembly” is to conduct a ritual whereby a sacredness is conferred on those participating. The participants commonly understand both the spirit of the ritual and the symbols contained in it, or through which it is enacted. Importantly, the ritual activities of the Masonic Lodge are among those symbols. The experience of the initiate is necessary to understanding those symbols. Mozart, through his music, drew on these symbols, including the experiential ones, when he wrote works that conveyed or expressed his belief in Masonic ideals and thought.

Henry lays out a number of characteristics of true Masonic works; these go beyond the symbols frequently assumed by the non-initiate, such as the obvious appearance of threes—groupings of three instruments or accidentals in a key signature. Features which do signify genuinely Masonic music are less overt, inspired by both the physical arrangement of the Lodge and the procedures of the ceremonies. Henry cites the placement of lamp stands and columns; various kinds of steps—in procession or ascending to the Grand Master’s chair; auditory events like knocking, clapping, or the strokes of a mallet; and progressions from chaos to order, darkness to light, or raw/unformed to precisely shaped. Henry believes that Mozart did not finish his Requiem—not because of lack of time or illness, but rather because the material missing from the torso that we have in his own writing is the same length as his Masonic cantata, “Laut verkünde unssre Freude”, K. 623, completed in mid-November 1791. He argues that “for the freemasons of the eighteenth century, these two sets of beliefs (Christianity and Masonry) were perfectly reconcilable”. In his opinion, whether writing a mass or a Masonic cantata, Mozart “presented an identical vision of his conception of divinity” (p. 118).

Mozart's "Laut verkünde unssre Freude”, K. 623

Christoph Prégardien, tenor; Helmut Wildhaber, bass; Chorus Viennensis; Wiener Akademie, conducted by Martin Haselböck.

Christoph Prégardien, tenor; Helmut Wildhaber, bass; Chorus Viennensis; Wiener Akademie, conducted by Martin Haselböck.

Perhaps more to the point, can a non-Mason such as myself (prohibited by my gender from the fraternity) perceive Masonic significance in the Requiem? I believe that once Masonic ideals and practices available to the uninitiated are identified, such symbolism in the Requiem’s musical landscape is indeed evident and recognizable by the diligent listener. Some of it relates to the Mason’s search for “greater light”, and some of it is established on a central Masonic ritual, that of the Third Degree, in which the candidate is “raised” to the status of Master Mason. Within that degree work, the candidate is at one point blindfolded and undergoes the re-enactment of the legendary death of Hiram Abiff, the Grand Master Mason whom King Solomon had hired to direct the building of the great Temple in Jerusalem. According to the legend, Hiram was murdered by treacherous workers who tried to extract from him the master password that would give them access to building jobs anywhere in the world; these villains then buried Hiram’s body in an unidentified grave. After much searching, Hiram’s grave was finally discovered by faithful “Fellow Craft” masons, trusted workers, and his decomposed body was raised up from that grave by Solomon himself. In reenacting that moment in the Third Degree ritual, the candidate is lifted by a special grip, and the blindfold is ripped away from his eyes so that after the period of darkness (reenacting Hiram’s burial) he suddenly sees light. He is also given the “substitute Masonic word”, the lost original of which Hiram’s murderers tried to extract from him with violence. The candidate is thus a Master Mason, an accepted member of the craft. It is to this ritual that Mozart alluded in a letter to his father in 1787, when Leopold had become quite ill and was facing death; Leopold, too, was a Mason, and knew the lesson of the Third Degree. And Mozart, writing the Requiem four years later, was undoubtedly remembering not to fear death, for it “is the key which unlocks the door to our true happiness” (Mozart’s letter translated by Emily Anderson).

The core of the Hiram legend is in the progression from the trauma of death, through burial, to the re-emergence of the corpse from the grave (by the action of human beings rather than with divine aid). This core encompasses a moment of transition, dramatically enacted in the Third Degree ritual. I believe that Mozart actually envisions that process in the Introit of the Requiem. To recognize how this occurs, we must first remember that the Introit is in three textual sections—an antiphon, then a psalm, and a return of the antiphon; the music replicates this textual structure. The antiphon is the opening material that gives the Requiem Mass its name:

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine, et lux perpetual luceat eis

(Rest eternal grant them, Lord, and may eternal light illumine them).

The following psalm, though, is a little-remarked feature of the Introit. It is the first two verses of Psalm 64/65:

1. Te decet hymnus Deus in Sion, et Tibi redetur votum in Jerusalem.

2. Exaudi orationem meam, ad te omnis caro veniet

(A hymn is owed to you, God, in Zion, and a vow to you will be fulfilled in Jerusalem.

Hear my prayer, to you all flesh shall come).

Let's Listen to the Entire Introit

Mozart's "Requiem" Introit

Ileana Cotrubas, soprano | Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Chorus

Academy of St. Martin in the Fields | Sir Neville Marriner, conductor

Ileana Cotrubas, soprano | Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Chorus

Academy of St. Martin in the Fields | Sir Neville Marriner, conductor

Mozart's Introit: Focus on the Psalm

Now, it’s important to focus for a moment on the psalm within the Introit. Remember that a psalm verse is laid out in two distinct “halves”. Typically in Mozart’s time this text in a requiem was set to Psalm Tone I, an ancient chant rising on the first three notes of a major scale to a repeated chanting note, and keeping the same chanting note through both halves of verse. Mozart, however, chose a different Psalm Tone, the “Tonus peregrinus”, or “wandering tone”.

Unlike Psalm Tone I, the Tonus peregrinus begins with a scale step upward and then returns to the chanting note; but the chanting note changes, dropping one pitch level in the second half of each verse. This Psalm Tone, called the “wandering tone”, is strongly associated with Psalm 113/114, “In exitu Israel de Aegypto”, recalling the deliverance of the Hebrews from bondage in Egypt:

When Israel went out from Egypt, the house of Jacob from a people of strange language,

Judah became God’s sanctuary, Israel his dominion.

Mozart's Psalm Tone- Connection to the Lutheran Chorale

It is highly significant that Mozart’s version of this chant conforms not to the Catholic liturgical form, as given above, but rather to the modified version used for the German Lutheran chorale (hymn), “Meine Seele erhebet den Herrn”, the translation of “Magnificat anima mea” (My soul magnifies the Lord). The chorale tune in the highest voice and longer notes clearly shows the rising third at the beginning, differentiating it from the Catholic liturgical usage of the Tonus peregrines.

J.S. Bach's “Meine Seele erhebet den Herrn”,

Christian Barthen an der Rieger-Orgel

Christian Barthen an der Rieger-Orgel

Mozart's Reference to Movement 10 of Bach's "Magnificat"

In this chorale, the melody taken from the chant begins not with a scale step but rather by an upward leap of a minor third, and then returns to the original pitch, which then serves as the chanting note for the first half of the verse. It is this melody to which Mozart set the psalm in the Introit of the Requiem. I view Mozart’s use of this Lutheran form of the chant as not at all accidental or coincidental but rather a deliberate choice because of a layering of meanings associated with the German form of the Tonus peregrinus. In using the Lutheran form of this special chant, Mozart appears to be alluding to or recalling J. S. Bach’s “Magnificat”, BWV 243, which he very likely saw or even heard in Leipzig two years before he wrote the Requiem.

Bach’s grand work, in D major, is set in movements, the tenth (time mark 22:26 below) of which is the only one in which the Lutheran “Magnificat” melody occurs. Here, it is not part of the vocal milieu but rather a solo oboe obbligato riding above a contrapuntal trio of treble voices and instruments. The Latin text that Bach was setting is Suscepit Israel puerum suum, recordatus misericordiae suae (He has helped his servant Israel, remembering his mercy). I think that in Mozart’s mind this Magnificat verse commemorating deliverance called to mind the Masonic view of death as deliverance, the beginning of a transition to “greater light…hope and joy…eternity”, as goes the lesson to the newly raised Mason (Duncan’s Ritual). Identifying the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and their crossing both the Red Sea and the Jordan River to arrive at the Promised Land, Psalm 113/114 and the tenth movement of the Magnificat and Psalm 64/65 all capture the meaning of transition, of tribulation and release from suffering, of attaining “home” because of God’s saving actions. Bach wordlessly made the connection in his Magnificat. Mozart later overlaid the Psalm in his Requiem’s Introit with this message. The correlation to the Masonic view of death as transition from earthly life to eternity is evident. Moreover, the correspondence of Mozart’s usage with Bach’s for the same purpose suggests that Mozart likely knew Bach’s application of the Psalm tone in the Magnificat, and appropriated it, exactly in the Lutheran form of the great canticle of praise, at the point in his Requiem where a “hymn” is “due to God in Jerusalem”.

JS Bach's "Magnificat" (10th movement at time mark 22:26)

Netherlands Bach Society | Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

Julia Doyle, soprano 1 | Hana Blažíková, soprano 2 | Maarten Engeltjes, alto | Thomas Hobbs, tenor | Christian Immler, bass

Netherlands Bach Society | Jos van Veldhoven, conductor

Julia Doyle, soprano 1 | Hana Blažíková, soprano 2 | Maarten Engeltjes, alto | Thomas Hobbs, tenor | Christian Immler, bass

A New Overview of Mozart's Introit

So, knowing how the Psalm functions in the Introit of Mozart’s Requiem, we can perceive the whole Introit in a new way. First of all, notice that the entire Introit is set as a stately, solemn march. Jacques Henry notes that such marches are integral to Masonic ceremony. Then, note that in Mozart’s Introit the Psalm forms a bridge between two treatments of the Antiphon, Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. The first antiphon statement begins as a tightly formed series of imitative entrances in D minor carrying the first phrase of the text. After another seven measures, the contrapuntal texture gives way a clear chordal presentation of the text “et lux perpetua” (and eternal light), in the brighter F major, without the orchestral accompaniment, so as to be completely unobscured, totally obvious. The orchestra’s subtle return in the middle of “perpetua” drives toward a second statement of et lux perpetua, again unaccompanied, at a higher pitch in the soprano, driving toward an even higher “luceat”, which is reinforced in the woodwinds and strings. “…Eternal light illumine them” would be a strongly Masonic vision.

Following this text passage, the orchestra begins a contrapuntal interlude that forms the basis for the accompaniment to the Psalm tone and to the later return of the Antiphon text. Then, in measure 21, the Psalm tone enters as a soprano solo floating over the contrapuntal working of the orchestra, very like the oboe’s high placement over contrapuntal voices in Bach’s Magnificat. The psalm’s second verse, exaudi orationem… (hear my prayer), is presented by the chorus; here the Psalm tone in the soprano is a cantus firmus over a contrapuntal accompaniment set in antiphonal style—call and response—in the lower three voices. The style of these three voices suggests a calling out, a seeking for a response, as the text requests.

After the psalm, the setting of the returning Antiphon is quite transformed. The contrapuntal texture continues, but its structure has changed. It is no longer the confined, tightly spaced series of imitative entrances and very close contrapuntal weaving that it was at the beginning of the Introit but rather a more active counterpoint with two melodic ideas. This second statement of the Antiphon encompasses a significantly greater pitch span between the highest and lowest voices, ultimately proceeding to a highly energized double fugue (the Kyrie). The imagery of this return of the Introit is of an opening up, an emergence or liberation from a limited space—a grave?—to a place of light and vigorous liveliness. Following the expansion of the Requiem aeternam section, we meet once again the text et lux perpetua. As before, it is highlighted, but this time (mm. 43 and 44) the choral sopranos are accompanied by a special “masonic” sound of four chords of wind instruments—bassett horns and bassoon, with trumpet and timpani—instead of the lower three voices, as in the first Antiphon setting. Jacques Henry states that the Masonic music of Mozart that uses this kind of instrumentation forms “what, in Lodges, are still called ‘columns of harmony’” (p. 19), an ideal of Masonic brotherhood. The sonic environment is a solemn, ceremonial one, and the rhythm of these wind chords possibly evokes or mimics knocking in the Masonic ritual. In any case, with the setting of et lux perpetua luceat eis Mozart calms the music and brings it to a half cadence, preparing for the beginning of the next section of the liturgy, the vigorous double feud “Kyrie eleison”.

Following this text passage, the orchestra begins a contrapuntal interlude that forms the basis for the accompaniment to the Psalm tone and to the later return of the Antiphon text. Then, in measure 21, the Psalm tone enters as a soprano solo floating over the contrapuntal working of the orchestra, very like the oboe’s high placement over contrapuntal voices in Bach’s Magnificat. The psalm’s second verse, exaudi orationem… (hear my prayer), is presented by the chorus; here the Psalm tone in the soprano is a cantus firmus over a contrapuntal accompaniment set in antiphonal style—call and response—in the lower three voices. The style of these three voices suggests a calling out, a seeking for a response, as the text requests.

After the psalm, the setting of the returning Antiphon is quite transformed. The contrapuntal texture continues, but its structure has changed. It is no longer the confined, tightly spaced series of imitative entrances and very close contrapuntal weaving that it was at the beginning of the Introit but rather a more active counterpoint with two melodic ideas. This second statement of the Antiphon encompasses a significantly greater pitch span between the highest and lowest voices, ultimately proceeding to a highly energized double fugue (the Kyrie). The imagery of this return of the Introit is of an opening up, an emergence or liberation from a limited space—a grave?—to a place of light and vigorous liveliness. Following the expansion of the Requiem aeternam section, we meet once again the text et lux perpetua. As before, it is highlighted, but this time (mm. 43 and 44) the choral sopranos are accompanied by a special “masonic” sound of four chords of wind instruments—bassett horns and bassoon, with trumpet and timpani—instead of the lower three voices, as in the first Antiphon setting. Jacques Henry states that the Masonic music of Mozart that uses this kind of instrumentation forms “what, in Lodges, are still called ‘columns of harmony’” (p. 19), an ideal of Masonic brotherhood. The sonic environment is a solemn, ceremonial one, and the rhythm of these wind chords possibly evokes or mimics knocking in the Masonic ritual. In any case, with the setting of et lux perpetua luceat eis Mozart calms the music and brings it to a half cadence, preparing for the beginning of the next section of the liturgy, the vigorous double feud “Kyrie eleison”.

Kyrie eléison. Christe eléison.

Lord, have mercy. Christ, have mercy.

"Requiem" Kyrie eleison

Pamela Heuvelmans, soprano | Barbara Werner, alto | Robert Morvaj, tenor | Thomas Pfeiffer, bass

Chamber Choir of Europe | Nicol Matt, conductor

Pamela Heuvelmans, soprano | Barbara Werner, alto | Robert Morvaj, tenor | Thomas Pfeiffer, bass

Chamber Choir of Europe | Nicol Matt, conductor

Masonic Imagery in the Communion (time mark 45.53)

Echoing the Introit’s imagery, Mozart designed the Communion toward the conclusion of the Requiem to further reflect the Masonic message and symbolism. Here the text is:

Lux aeterna luceat eis, Domine, cum sanctis tuis in aeternum, quia pius es.

May light eternal shine on them, Lord, with your saints for ever, for you are gracious.

This is not a genuine Psalm verse, in spite of its two-part structure, yet Mozart again set it to the Tonus peregrinus; in fact, this text marks the place where the music of the Introit is brought back with virtually no change except for necessary accommodations for setting the new text. And once more, Masonic symbolism is at play. As in the Introit, the soprano solo carries the melody above the orchestra, ensuring the greatest ease of recognition. The luminosity of the soprano’s range suggests the light to which the text alludes and corresponds with the Masonic search for “more light”.

"Requiem" Lux aeterna

Artist: Maria Stader | Münchener Bach-Chor

Münchener Bach-Orchester | Karl Richter, conductor

Artist: Maria Stader | Münchener Bach-Chor

Münchener Bach-Orchester | Karl Richter, conductor

Certainly these remarks are far from a complete exploration of the Masonic connection in Mozart’s Requiem. For those who are Masons, though, this famous work should arouse considerable curiosity and engender much further study!

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2017

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2017

Mozart's "Requiem"

Orchestre National de France | James Gaffigan, conductor

Marita Solberg, soprano | Karine Deshayes, mezzo | Joseph Kaiser, tenor | Alexander Vinogradov, bass

Chœur de Radio France, Nicolas Fink, choir director

Orchestre National de France | James Gaffigan, conductor

Marita Solberg, soprano | Karine Deshayes, mezzo | Joseph Kaiser, tenor | Alexander Vinogradov, bass

Chœur de Radio France, Nicolas Fink, choir director

|

|

Time Markers for Movements:

I. Introitus: Requiem aeternam (choir with soprano solo) (1:19) II. Kyrie (choir) (5:46) III. Sequentia: - Dies irae (choir) (8:14) - Tuba mirum (solo quartet) (10:09) - Rex tremendae majestatis (choir) (13:32) - Recordare, Jesu pie (solo quartet) (15:31) - Confutatis maledictis (choir) (20:27) - Lacrimosa dies illa (choir) (22:48) IV. Offertorium: - Domine Jesu Christe (choir with solo quartet) (25:52) - Versus: Hostias et preces (choir) (29:29) V. Sanctus (choir) (32:52) VI. Benedictus (solo quartet and choir) (34:30) VII. Agnus Dei (choir) (38:52) VIII. Communio: - Lux aeterna (soprano solo and choir) (41:45) |

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.