- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

CHAMBER MUSIC PROGRAM NOTES

by Judith Eckelmeyer

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Benedetto Lupo, piano

Wednesday, February 10, 1988

Gartner Auditorium

Gartner Auditorium

Program

Robert Schumann (1810-1856): Three Romances, Op. 28

Sehr markiert

Einfach

Sehr markiert--Intermezzo I: Presto--Intermezzo II: Etwas langsamer--Wie vorher

Sehr markiert

Einfach

Sehr markiert--Intermezzo I: Presto--Intermezzo II: Etwas langsamer--Wie vorher

Schumann: Sonata No. 2 in G minor, Op. 22

So rasch wie möglich--Più presto--Prestissimo

Andantino

Scherzo: Sehr rasch und markiert

Rondo: Presto--Prestissimo

So rasch wie möglich--Più presto--Prestissimo

Andantino

Scherzo: Sehr rasch und markiert

Rondo: Presto--Prestissimo

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953): Father Lorenzo, Masks, The Montagues and Capulets, Mercutio, and Romeo bids Juliet farewell

from Ten Pieces from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 75

from Ten Pieces from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 75

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943): Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36

Allegro agitato--Meno mosso--Tempo I--Meno mosso--Non allegro--Lento--Poco più mosso--Tempo I--Allegro molto--Presto

Allegro agitato--Meno mosso--Tempo I--Meno mosso--Non allegro--Lento--Poco più mosso--Tempo I--Allegro molto--Presto

Program Notes by Judith Eckelmeyer

A great many words have been rendered on the nature of romanticism, which is often pigeonholed in the nineteenth century. At the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, descriptions and definitions were a tangle of invective ("...the romantic [is] sickly"--Goethe) and euphoric enthusiasm ("...the essence of Romantic art lies in the artistic object's being free, concrete, and the spiritual idea in its very essence--all this revealed to the inner rather than to the outer eye..."--Hegel; "...liberalism..."--Hugo; "...the last resort of the human heart..."--Charles Nodier). Regardless of the contradictory opinions of the phenomenon, we are "stuck" with the term and almost cemented into a nineteenth-century time frame for it.

However, romanticism in music, no less than in the other arts, is a phenomenon that precedes and endures beyond the nineteenth century. A principal feature by which "romanticism" might be attributed to a composer's style is expressivity, often perceived as a focus on melodies along with colorful harmonies and wide dynamic contrasts. As we shall see these characteristics are not bound by century lines.

Schumann, Prokofiev, and Rachmaninov, whose lives and careers spanned more than a century, created musical works that share unusual commonalities of a romantic persuasion. In the sphere of piano genres, they all borrowed from the tradition of sonata and concerto writing, but they also established a body of character pieces in their highly evocative, unique styles. And in addition, they approached the process of composition to a great extent through the vehicle of melody, which they used not only as an expressive tool but as a unifying device as well.

Schumann, Prokofiev, and Rachmaninov, whose lives and careers spanned more than a century, created musical works that share unusual commonalities of a romantic persuasion. In the sphere of piano genres, they all borrowed from the tradition of sonata and concerto writing, but they also established a body of character pieces in their highly evocative, unique styles. And in addition, they approached the process of composition to a great extent through the vehicle of melody, which they used not only as an expressive tool but as a unifying device as well.

Robert Schumann's immense output of intimate art songs indicates the extent to which melodism was a factor in his style. Having begun his career as a concert pianist, he not unexpectedly wrote many works for that instrument, works which contain a blend of the lyric art of the song writer with the virtuosic properties of a fine keyboard artist. But in addition, Schumann was a journalist, a music critic. His literary bent influenced his musical style through the figures of E.T.A. Hoffman's Kreisler and Schumann's own personalities--Florestan, Eusebius, and Raro--who people several cycles of his piano works. He also incorporated literary devices into the structure of his melodies by translating letters of names or anagrams into pitches; the melodies thus created were often reused, perhaps cloaked in virtuosic fabric, transformed from one rhythm to another, from one movement to another, or from one work to another.

Robert Schumann's immense output of intimate art songs indicates the extent to which melodism was a factor in his style. Having begun his career as a concert pianist, he not unexpectedly wrote many works for that instrument, works which contain a blend of the lyric art of the song writer with the virtuosic properties of a fine keyboard artist. But in addition, Schumann was a journalist, a music critic. His literary bent influenced his musical style through the figures of E.T.A. Hoffman's Kreisler and Schumann's own personalities--Florestan, Eusebius, and Raro--who people several cycles of his piano works. He also incorporated literary devices into the structure of his melodies by translating letters of names or anagrams into pitches; the melodies thus created were often reused, perhaps cloaked in virtuosic fabric, transformed from one rhythm to another, from one movement to another, or from one work to another.

The Three Romances of 1839 are the product of Schumann's creative spurt so clearly evident in the 1838 cycles Kreisleriana and Kinderszenen, the revision of the second sonata, and the composition of a number of other single-movement character pieces for piano. The Romances are melodically oriented and very picturesque. The first, in B-flat minor, is an impassioned and glittering drama of almost Chopinesque etude quality. The second is marked "Einfach" (simple) and its melody dwells serenely within the gently rocking accompanying figures of both hands, above and below it. The third is a well-marked march, very chordal and regulated, which yields to other sections that are softer in rhythm but clearly derived melodically from the march.

The Sonata in G minor, Op. 22, was begun in 1833, well before Schumann's romantic involvement with Clara Wieck, although at the time when he was thinking about entering the world of journalism in partnership with her father. By 1835 the sonata was completed, but Schumann decided to alter the last movement in 1838, while he was deeply involved in writing for the piano. The sonata was published in 1839 with a dedication to Henriette Voigt, a close but evidently platonic friend. The work is in four highly contrasted movements. Astutue listening reveals an interconnection of thematic materials within the first movement, in spite of the virtuosic environment, and with the last. The second movement is clearly an exquisite "song" without words, while the third contains a transcribed Lied, "Im Herbst," which Schumann had composed in 1828 on a text of Justinus Kerner.

Sergei Prokofiev never formally emigrated from Russia, but he spend nearly twenty years in western Europe, particularly in Paris, after finishing his training at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1914. Paris was the sphere of Diaghilev and Stravinsky, whose Rite of String had caused riots in 1912; but 1914, the specter of tonal breakdown had been heard in Schoenberg's Erwartung and Pierrot Lunaire. After a period of experimentation with severe dissonance and harsh sounds, Prokofiev returned home and modified his style to the conservative taste of post-revolutionary Russia, expanding his capability for character depiction and broad, arching melodies, which were especially useful to him in writing music for the ballet.

Romeo and Juliet, complete in 1935, was Prokofiev's first full-length ballet in three acts, very much in the narrative drama format of Tchaikovsky's major ballets. In spite of the fact that they had encouraged Prokofiev to write the work, the Kirov Theater management did not mount a production of the ballet, and the Bolshoi in Moscow later rejected it. Under these circumstances, Prokofiev adapted the ballet into two orchestra suites and a set of ten piano character pieces, all of which were published in 1936. The full ballet was performed for the first in time Brno, Czechoslovakia, in 1938, well after the adaptations had been heard in concert performances.

As with Schumann's work, Prokofiev's focus is on melodic detail in this music. Although these character sketches are intended for the dance they are all memorably tuneful with unique harmonic and rhythmic subtleties. Yet here too, the listener will recognize that Prokofiev drew his melodic material largely from a single germ cell, which he transformed in mood and color to fit each character.

As with Schumann's work, Prokofiev's focus is on melodic detail in this music. Although these character sketches are intended for the dance they are all memorably tuneful with unique harmonic and rhythmic subtleties. Yet here too, the listener will recognize that Prokofiev drew his melodic material largely from a single germ cell, which he transformed in mood and color to fit each character.

Despite having created most of his works in the first half of this century, Sergei Rachmaninov wrote in the vein of expressive melodies and harmonic colorism closely associated with the nineteenth century. His harmonic language is richer in chromaticism and extended and altered chords than Schumann's, and less astringent in dissonance than Prokofiev's. But there can be little doubt that Rachmaninov eschewed the theory-driven revolution of Schoenberg in favor of emotional, even moody evocations of a haunting quality.

Trained as a pianist, composer, and conductor at the St. Petersburg and Moscow Conservatories, Rachmaninov made his foreign debut in London in 1899, and ten years later toured the United States; by this time he had already written and performed his three piano concerts, the cello sonata, the firs symphony, and an opera. Returning to Russia, he re-entered the compositional aspect of his career with the preludes and the choral liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in 1910. By 1913 he had written the second piano sonata, whose sectional tempo changes and stylistic variety often obscure the movement structure but lend urgency and restlessness to the music, heightening its dramatic passionate idiom. The emotional content is supported by a very tight structural cohesion brought about through the use of variants of the principal theme throughout the work.

After leaving Russia in 1917 and emigrating (via Stockholm) to the United States, Rachmaninov revised this sonata in 1931, believing that it had "too much unnecessary movement of the voices and [was] too long." Even so, there is plenty which remains to draw the listener through episodes of high drama, tragedy, ecstatic lyricism, and contemplative serenity, through wild displays of bravura arpeggio passages to thundering hell-like chords to sumptuous melodies. Passionate explosions of sound contrast lulling moments. This sonata provides a sure rebuttal to the nation that romanticism died at the end of the nineteenth century!

Judith Eckelmeyer © 1988

As Benedetto Lupo's performance is not available on YouTube, please enjoy these performances:

Schumann's Three Romances, Op. 28, 2. Einfach

Tatiana Nikolayeva, piano

Tatiana Nikolayeva, piano

Schumann's Sonata No. 2 in G minor, Op. 22

Rafał Blechacz, piano

Rafał Blechacz, piano

Prokofiev's Ten Pieces from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 75

Friar Lawrence, piano

Friar Lawrence, piano

Rachmaninov's Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36

Daniel Hsu, piano

Daniel Hsu, piano

Complete Program PDF

To read online scroll down using mouse over document.

Note the blank area on cover page- keep scrolling!

To download use downward facing arrow on lower right side.

Note the blank area on cover page- keep scrolling!

To download use downward facing arrow on lower right side.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

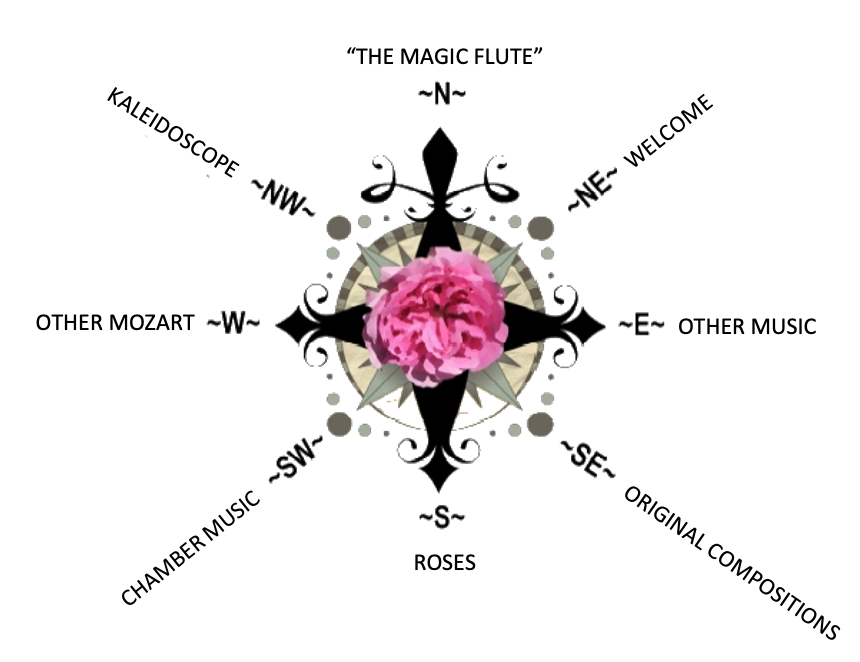

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.