- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

PROGRAM NOTES: APRIL 18, 2014

GOOD FRIDAY CONCERT

TRINITY CATHEDRAL, CLEVELAND

APRIL 18, 2014

TRINITY CATHEDRAL, CLEVELAND

APRIL 18, 2014

The heightening of the season of Lent during Holy Week provides opportunities for composers to treat highly charged texts in intensely personal ways. Liturgy, scripture, and sacred poetry are sources for the three composers on this evening’s program: Gregorio Allegri, Francis Poulenc, and Maurice Duruflé. Each in his own way helps our reflection on this special season.

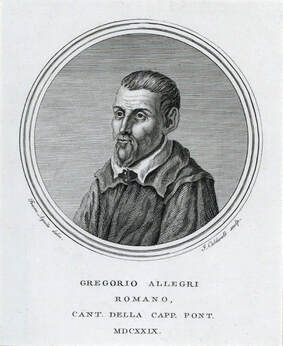

Gregorio Allegri (1582-1662) spent the bulk of his life as a chorister, music director, composer, and priest in Rome. The most important part of his career came after 1629 when he served as a singer in the papal choir. During this time he created a number of motets, the most famous of which is his “Miserere”, a setting for nine voice parts of the first twenty verses of the penitential Psalm 51. The work became a customary component of the Tenebrae service and was performed on Wednesday and Friday in Holy Week in the Papal (Sistine) Chapel.

It is worth remembering that in the Papal Chapel only male singers performed (with no instrumental accompaniment). From the mid-17th century on, the motet’s fame enticed editors and composers to introduce changes into the motet’s performing forces and content, eventually scoring the work for women as well as men. John Rutter’s edition for this evening’s performance derives from Allegri’s time but can be sung by male and female singers.

The musical forces in the “Miserere” are organized into two choirs. Choir I is a full ensemble comprised of two soprano parts, altos, tenors and basses presenting simple, fairly static melodies harmonized in chords, with brief moments in chant style and occasional very limited counterpoint. Choir II is a solo ensemble of two sopranos, alto, and bass, who introduce more active, typical early Baroque rhythms as well as extreme ranges—up to a high C for the top soprano. Choir I and Choir II alternate in the presentation of harmonized psalm verses; between the ensemble verses, men chant a verse in unison. Thus, as the motet progresses, there are three sonorities in regular rotation: Choir I’s multi-voice ensemble in harmony, followed by unison chanting by men, then Choir II’s four soloists singing more actively in harmony; then plainchant again, then the large ensemble, and so on. This pattern continues till the middle of the psalm’s 20th verse, at which point the two choirs join into a nine-part ensemble to complete that verse and end the motet. The simple harmonic beauty, the fascinating alternation of performing sonorities, the breathtaking ornamental working of the soloists’ ensemble, and the magnificent nine-voice conclusion combine with the passionate psalm text to form an extraordinary experience for those who hear this motet.

So striking was the impact of Allegri’s “Miserere” that it was kept in strictest security for many decades. The 18th –century historian Charles Burney reported that no one could copy or take parts out of the chapel under pain of excommunication! (It turns out that several copies were made and given out with official imprimatur; one even reached London, where it was printed in 1771.) As Otto Jahn tells us, no less a figure than the 14-year-old Mozart, in Rome with his father for Holy Week, heard the work at the Wednesday service and afterward wrote it down from memory, then made a few corrections at the Friday performance. Although papa Leopold was at pains to keep Mozart’s feat a secret, word got out, and Wolfgang was obliged to perform the “Miserere” for the astounded Papal singer Christofori. Mercifully, he was never chastised for his offence to the church; Jahn reports that he was honored for his feat of memory.

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), was born and raised in Paris, learned piano as a child from his mother, and was introduced through her and her brother into a highly secular world of contemporary French literature and music. Poulenc’s father, whom he described as a “deeply religious but liberal” Catholic from the south of France, died in 1917, after which Francis moved in the spheres of his mother’s secular, cosmopolitan world. As a teen, he studied the piano music of Debussy and Ravel, then met Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud—three of Les Six—and Eric Satie, their older friend and guide to the avant-garde. At the age of 18 he dedicated his first published work to Satie and became associated with the iconoclastic Six. Although he eventually studied composition formally, it was with private teachers rather than in a classically structured program; he famously progressed no further in counterpoint than Bach’s chorales in spite of having met and conversed with Schoenberg and his pupils in 1921 in Vienna. In this highly individualistic and open-ended development, Poulenc acquired the diversity of resources that would characterize his music: sensitivity to harmonic and tonal color, melodic freedom, and the “language” of popular music current in Parisian cafes and theaters.

Poulenc’s world changed in 1936 when his friend, composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud, was killed in a car accident. In the wake of this tragedy Poulenc retired to Rocamadour, a pilgrimage town in the southern region from which his father had come. There, Poulenc returned to religious faith. His very first sacred choral pieces, “Litanies to the Black Virgin” of 1936, are settings for women’s and children’s voices of recitations honoring the Virgin who is represented by a blackened wood statue in the church of Notre Dame in Rocamadour. Other sacred choral works followed soon after and appear throughout the rest of his life.

Poulenc composed the Four Motets for a Penitential Time shortly after finishing his Mass in G in 1937; “Vinea mea electa”, and “Tenebrae factae sunt” and “Tristis est anima mea” were completed in 1938 and “Timor et Tremor” in 1939. The texts are very old poems conflating and adapting Biblical passages from Psalm 55 (“Timor et tremor”), the Gospels (“Tenebrae factae sunt” and “Tristis est anima mea”), and Isaiah 5 (“Vinea mea electa”).

If one had no idea of the subject matter, one might say the motets were studies in varieties of dissonance. Yet as we know, dissonance comes in many flavors, from intensely bitter, to harsh, to melancholy, to poignantly sweet. To attain his remarkable chord constructions in these motets, Poulenc almost everywhere divided the traditional SATB parts. He was a master at choosing just the right combination of pitches to help define the emotional values of the texts, and he also intensified the choral effects through the vocal ranges. Poulenc thought his sacred choral music represented “the best and most genuine part” of himself; indeed, all of the harmonic and textural attributes in these motets reflect his absolute dedication to reaching into the depths of texts.

Each penitential motet has remarkable sonic detail. Some examples to listen for:

In “Timor et tremor”, “darkness” lies in very low ranges for altos, tenors and basses. In the plea to avoid ruin, at the end, the word “Domine”—“Lord”—is set to shocking dissonance and the word “confundar”—“ruin”—is a treacherous chromatic passage.

“Vinea mea electa”, the gardener’s song of love for his vineyard, begins with lush, full, lovely harmonies but becomes intensely dissonant with the bitterness of betrayal—the beloved radically changes, crucifying her husbandman and releasing the criminal Barabbas.

“Tenebrae factae sunt” begins with the darkness of the low alto and bass voices, reaching to extraordinary outbursts at “Jesus exclaimed”. Jesus’s words, devastatingly restrained in their setting, are followed by the depiction of his bowing his head and yielding his spirit.

“Tristis est anima mea” is set for the usual four choral parts with a soprano soloist, who begins the piece with the words of deathly sorrow Jesus speaks to his disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane. Jesus’s prediction of the disciples’ flight is vivid, and his first statement that he is going to be sacrificed for them is tumultuous. But Poulenc set the second presentation of this statement in full, rich eight-voice chorus, with the luminous soprano transforming Jesus’s words into light.

Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986) was born into a devout family in Louviers, near Rouen, where his foundation of ties with the organ, the church and its liturgy was established. Playing the family harmonium as a child of six opened his interest in the organ, which he began to study in earnest from the age of 10 at the choir school of Rouen Cathedral. There as a choirboy he also became formally educated in plainchant—a fact that must lead us on a short tangent:

Plainsong, or plainchant, had been the sung vehicle for the liturgy of the Roman Catholic church since the fifth and sixth centuries. A body of integrated Gallican and Roman chant became known as Gregorian chant, named for Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590-604), who had promoted the development of a body of chants for the church. Over the centuries various additions and modifications, along with notational systems to enable easy memorization of the vast literature, affected this repertory, even leading to significant alterations of the Gothic melodies; but the bones of Gregorian chant remained in place as the church’s musical language. In France, the Revolution beginning in 1789 secularized that country, effectively destroying not only the power of the clergy but also generally removing the practice of singing the liturgy. A few pockets remained where the chant was retained, but it was used in greatly simplified ways, sung with chordal major or minor harmony in stodgy rhythms. (An excellent discussion of this style may be found in James Frazier’s “In the Gregorian Mode” and Jeffrey Reynolds’s “On Clouds of Incense” in Maurice Duruflé, 1902-1986: The Last Impressionist, ed. Ronald Ebrecht, 2002.)

In the 1830s, Benedictine monks in the Abbey at Solesmes, southwest of Paris, began a huge project of restoring the chants to their original notation of rhythm and pitches—as far as could be determined—and working out a performance practice to sing the liturgy as they thought it originally had been sung. No longer were the chants harmonized, but sung in unison, with notes rhythmically grouped in twos or threes, conforming to the flow of the text. Further, instead of using major or minor scales, the chants’ melodies were in their original ancient modes. Louis Niedermayer, in 1855, and music historian Maurice Emmanuel, in 1913, built on the monks’ work by developing methods of modal accompaniment for the chant. The impact of the Solesmes monks’ work was so great as to inspire the establishment of the Scola Cantorum in 1894, and later the Institut grégorien de Paris, for training singers in this reformed style, and to further the development of church music and organ repertoire inspired by Gregorian chant and the polyphonic style of Palestrina. After several stages of refinement, reliable editions of the liturgy were published in the early 20th century. The effects of these reforms spread to French churches and schools with increasing intensity, and by the third decade of the 20th century many French composers were using both melodies and modal sounds of plainchant as serious components in their works.

Duruflé’s youthful training in plainchant in Rouen occurred in the context of the Solesmes movement. As will be apparent, this training was of paramount importance for Duruflé’s entire compositional career.

At age 17 Duruflé moved to Paris where he studied organ privately with Charles Tournemire, the organist at Sainte Clotilde, then with Louis Vierne at Notre Dame Cathedral, where he soon became Vierne’s assistant. A year later he entered Eugène Gigout’s organ class at the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied harmony and composition as well. (Among his colleagues in Paul Dukas’s harmony class was Olivier Messiaen, another composer whose sacred works would make an impact in the 20th century.) He distinguished himself with five “first prizes”, including in organ and composition, and other awards. By 1930 he was organist of the church of Sainte Étienne du Mont, and in 1943 became professor of harmony at the Conservatoire, and also taught organ there. He established himself as a superb organist as well as a teacher and composer. He became widely recognized in these spheres, even serving as the soloist for the premiere of the Organ Concerto by his contemporary, Francis Poulenc, in 1939.

Among Duruflé’s students was a brilliant organist, Marie-Madeleine Chevalier, whom he married in 1955. Maurice, and later he and Marie-Madeleine, had a highly successful concert career, travelling to England, Europe, Russia, and North Africa to give organ recitals. During five tours of North America Maurice conducted his increasingly popular Requiem, and he and Marie-Madeleine performed organ works to great acclaim. However, in 1975 the Duruflés were seriously injured in an automobile accident which ended Maurice’s concert career and limited Marie-Madeleine’s for a time; she recovered well enough that, after Maurice’s death in 1986, she was able to undertake successful tours and return again to the United States to perform and teach. Deteriorating health resulting from the auto accident increasingly weakened her, however, and she died in 1999.

Maurice Duruflé’s compositions are not numerous, but they are held in great esteem. The gem among them is the Requiem, Op. 9, dedicated to his father; it was given both a radio and a concert premiere in 1949 and quickly became a worldwide favorite. As mentioned earlier, performing plainchant in the Solesmes manner became as fundamental as breathing in Duruflé’s work as a church musician; it was a key ingredient in his compositional style. Just after his father’s death, he was working on a suite of organ pieces based on the plainchant of the Requiem Mass when the publisher Durand commissioned what became his Requiem. The completed work is for a mixed four-voice choir with soprano and baritone soloists (or choir section) and full orchestra; Duruflé also prepared a version with a reduced orchestra and organ accompaniment, as well as a version for organ alone. This evening’s performance uses organ and a reduced orchestra consisting of strings, timpani, three trumpets, and harp.

Duruflé’s Requiem is structured with the same movements as Fauré’s Requiem of some 50 years earlier, and has the same sense of peace and calm as Fauré’s. Both omit the doom-threatening “Dies irae” that is so strongly to the fore in both Mozart’s and Verdi’s Requiems, but both Fauré and Duruflé introduce turmoil in the “Libera me” movement. But, as he said himself, Duruflé’s work is not dependent on Fauré’s, for unlike Fauré, Duruflé constructed his movements on the liturgical chants that can be found in the Liber Usualis. The chants—and plainchant performing style—are integral to and recognizable in Duruflé’s work; he said he sought to “reconcile” the plainchant rhythms with the “exigencies” of modern metrical beats. However, the chants are not slavishly employed. They occasionally appear in different pitch ranges throughout a movement, suggesting traditional modulation techniques between sections; they are sung in chant-like unisons, or harmonized in the choral voices, or form the subject of a fugue section, as in the Kyrie. There are also occasional departures from plainchant. Nevertheless, Duruflé’s melodies live primarily in plainchant, and he created an instrumental accompaniment that supports the modality and free-flowing lines of these melodies. The harmonic language of the Requiem is quite mixed, at turns using the old medieval church modes or the classical major/minor tonal system. (Those interested should devour Jeffrey Reynolds’s analysis in “On Clouds of Incense”.) Harmonies are built of extended and often unresolved chords, a style Duruflé absorbed from Debussy’s music. Perhaps the most amazing effect appears at the very last chord, a gentle reminder of the meaning of the text.

Personal Afterword: It has been a rare treat to talk with Karen Holtkamp, of the Trinity community, about her own experiences with Maurice and Marie-Madeleine Duruflé. Her stories and comments allow us a special glimpse of the two.

Before she was married to Walter Holtkamp, Karen McFarlane became the Duruflés’ agent after the death in 1976 of their original agent, Lilian Murtagh. She has vivid and fond memories of her long association with both Maurice and Marie-Madeleine. Mrs. Holtkamp enjoyed the Duruflés tremendously, saying that they were fun to be with and had a very happy relationship. She described Marie-Madeleine as having an outgoing personality and a rich sense of humor, complementing Maurice’s quieter, more introspective personality.

As a virtuoso organist, though, Marie-Madeleine knew her own mind when it came to her performing. Visiting the Duruflés in their small Paris apartment, Mrs. Holtkamp was treated to Maurice’s performance of a Bach chorale prelude on their small pipe-organ. Then Marie-Madeleine performed Maurice’s “Fugue on Alain”. While she was playing, Maurice reached over and changed his wife’s registration. Marie-Madeleine changed it back. Again Maurice changed it, and Marie-Madeleine changed it back. The registration argument continued through the piece, much to Mrs. Holtkamp’s amusement.

Marie-Madeleine also adored cats. Mrs. Holtkamp recalls that in 1969, having just flown in to New York from Paris, the Duruflés were met by Fred Swann, organist at the Riverside Church. Fred later told Karen that almost the first thing Marie-Madeleine did was to ask after Karen’s cat Alleluya. Fred had to tell her that Alleluya was “defunct”. Turning to her husband, Marie-Madeleine exclaimed, “Oh, Maurice, you must write un petit requiem pour Alleluya!”

Our thanks to Mrs. Holtkamp for sharing these memories.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2014

It is worth remembering that in the Papal Chapel only male singers performed (with no instrumental accompaniment). From the mid-17th century on, the motet’s fame enticed editors and composers to introduce changes into the motet’s performing forces and content, eventually scoring the work for women as well as men. John Rutter’s edition for this evening’s performance derives from Allegri’s time but can be sung by male and female singers.

The musical forces in the “Miserere” are organized into two choirs. Choir I is a full ensemble comprised of two soprano parts, altos, tenors and basses presenting simple, fairly static melodies harmonized in chords, with brief moments in chant style and occasional very limited counterpoint. Choir II is a solo ensemble of two sopranos, alto, and bass, who introduce more active, typical early Baroque rhythms as well as extreme ranges—up to a high C for the top soprano. Choir I and Choir II alternate in the presentation of harmonized psalm verses; between the ensemble verses, men chant a verse in unison. Thus, as the motet progresses, there are three sonorities in regular rotation: Choir I’s multi-voice ensemble in harmony, followed by unison chanting by men, then Choir II’s four soloists singing more actively in harmony; then plainchant again, then the large ensemble, and so on. This pattern continues till the middle of the psalm’s 20th verse, at which point the two choirs join into a nine-part ensemble to complete that verse and end the motet. The simple harmonic beauty, the fascinating alternation of performing sonorities, the breathtaking ornamental working of the soloists’ ensemble, and the magnificent nine-voice conclusion combine with the passionate psalm text to form an extraordinary experience for those who hear this motet.

So striking was the impact of Allegri’s “Miserere” that it was kept in strictest security for many decades. The 18th –century historian Charles Burney reported that no one could copy or take parts out of the chapel under pain of excommunication! (It turns out that several copies were made and given out with official imprimatur; one even reached London, where it was printed in 1771.) As Otto Jahn tells us, no less a figure than the 14-year-old Mozart, in Rome with his father for Holy Week, heard the work at the Wednesday service and afterward wrote it down from memory, then made a few corrections at the Friday performance. Although papa Leopold was at pains to keep Mozart’s feat a secret, word got out, and Wolfgang was obliged to perform the “Miserere” for the astounded Papal singer Christofori. Mercifully, he was never chastised for his offence to the church; Jahn reports that he was honored for his feat of memory.

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), was born and raised in Paris, learned piano as a child from his mother, and was introduced through her and her brother into a highly secular world of contemporary French literature and music. Poulenc’s father, whom he described as a “deeply religious but liberal” Catholic from the south of France, died in 1917, after which Francis moved in the spheres of his mother’s secular, cosmopolitan world. As a teen, he studied the piano music of Debussy and Ravel, then met Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud—three of Les Six—and Eric Satie, their older friend and guide to the avant-garde. At the age of 18 he dedicated his first published work to Satie and became associated with the iconoclastic Six. Although he eventually studied composition formally, it was with private teachers rather than in a classically structured program; he famously progressed no further in counterpoint than Bach’s chorales in spite of having met and conversed with Schoenberg and his pupils in 1921 in Vienna. In this highly individualistic and open-ended development, Poulenc acquired the diversity of resources that would characterize his music: sensitivity to harmonic and tonal color, melodic freedom, and the “language” of popular music current in Parisian cafes and theaters.

Poulenc’s world changed in 1936 when his friend, composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud, was killed in a car accident. In the wake of this tragedy Poulenc retired to Rocamadour, a pilgrimage town in the southern region from which his father had come. There, Poulenc returned to religious faith. His very first sacred choral pieces, “Litanies to the Black Virgin” of 1936, are settings for women’s and children’s voices of recitations honoring the Virgin who is represented by a blackened wood statue in the church of Notre Dame in Rocamadour. Other sacred choral works followed soon after and appear throughout the rest of his life.

Poulenc composed the Four Motets for a Penitential Time shortly after finishing his Mass in G in 1937; “Vinea mea electa”, and “Tenebrae factae sunt” and “Tristis est anima mea” were completed in 1938 and “Timor et Tremor” in 1939. The texts are very old poems conflating and adapting Biblical passages from Psalm 55 (“Timor et tremor”), the Gospels (“Tenebrae factae sunt” and “Tristis est anima mea”), and Isaiah 5 (“Vinea mea electa”).

If one had no idea of the subject matter, one might say the motets were studies in varieties of dissonance. Yet as we know, dissonance comes in many flavors, from intensely bitter, to harsh, to melancholy, to poignantly sweet. To attain his remarkable chord constructions in these motets, Poulenc almost everywhere divided the traditional SATB parts. He was a master at choosing just the right combination of pitches to help define the emotional values of the texts, and he also intensified the choral effects through the vocal ranges. Poulenc thought his sacred choral music represented “the best and most genuine part” of himself; indeed, all of the harmonic and textural attributes in these motets reflect his absolute dedication to reaching into the depths of texts.

Each penitential motet has remarkable sonic detail. Some examples to listen for:

In “Timor et tremor”, “darkness” lies in very low ranges for altos, tenors and basses. In the plea to avoid ruin, at the end, the word “Domine”—“Lord”—is set to shocking dissonance and the word “confundar”—“ruin”—is a treacherous chromatic passage.

“Vinea mea electa”, the gardener’s song of love for his vineyard, begins with lush, full, lovely harmonies but becomes intensely dissonant with the bitterness of betrayal—the beloved radically changes, crucifying her husbandman and releasing the criminal Barabbas.

“Tenebrae factae sunt” begins with the darkness of the low alto and bass voices, reaching to extraordinary outbursts at “Jesus exclaimed”. Jesus’s words, devastatingly restrained in their setting, are followed by the depiction of his bowing his head and yielding his spirit.

“Tristis est anima mea” is set for the usual four choral parts with a soprano soloist, who begins the piece with the words of deathly sorrow Jesus speaks to his disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane. Jesus’s prediction of the disciples’ flight is vivid, and his first statement that he is going to be sacrificed for them is tumultuous. But Poulenc set the second presentation of this statement in full, rich eight-voice chorus, with the luminous soprano transforming Jesus’s words into light.

Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986) was born into a devout family in Louviers, near Rouen, where his foundation of ties with the organ, the church and its liturgy was established. Playing the family harmonium as a child of six opened his interest in the organ, which he began to study in earnest from the age of 10 at the choir school of Rouen Cathedral. There as a choirboy he also became formally educated in plainchant—a fact that must lead us on a short tangent:

Plainsong, or plainchant, had been the sung vehicle for the liturgy of the Roman Catholic church since the fifth and sixth centuries. A body of integrated Gallican and Roman chant became known as Gregorian chant, named for Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590-604), who had promoted the development of a body of chants for the church. Over the centuries various additions and modifications, along with notational systems to enable easy memorization of the vast literature, affected this repertory, even leading to significant alterations of the Gothic melodies; but the bones of Gregorian chant remained in place as the church’s musical language. In France, the Revolution beginning in 1789 secularized that country, effectively destroying not only the power of the clergy but also generally removing the practice of singing the liturgy. A few pockets remained where the chant was retained, but it was used in greatly simplified ways, sung with chordal major or minor harmony in stodgy rhythms. (An excellent discussion of this style may be found in James Frazier’s “In the Gregorian Mode” and Jeffrey Reynolds’s “On Clouds of Incense” in Maurice Duruflé, 1902-1986: The Last Impressionist, ed. Ronald Ebrecht, 2002.)

In the 1830s, Benedictine monks in the Abbey at Solesmes, southwest of Paris, began a huge project of restoring the chants to their original notation of rhythm and pitches—as far as could be determined—and working out a performance practice to sing the liturgy as they thought it originally had been sung. No longer were the chants harmonized, but sung in unison, with notes rhythmically grouped in twos or threes, conforming to the flow of the text. Further, instead of using major or minor scales, the chants’ melodies were in their original ancient modes. Louis Niedermayer, in 1855, and music historian Maurice Emmanuel, in 1913, built on the monks’ work by developing methods of modal accompaniment for the chant. The impact of the Solesmes monks’ work was so great as to inspire the establishment of the Scola Cantorum in 1894, and later the Institut grégorien de Paris, for training singers in this reformed style, and to further the development of church music and organ repertoire inspired by Gregorian chant and the polyphonic style of Palestrina. After several stages of refinement, reliable editions of the liturgy were published in the early 20th century. The effects of these reforms spread to French churches and schools with increasing intensity, and by the third decade of the 20th century many French composers were using both melodies and modal sounds of plainchant as serious components in their works.

Duruflé’s youthful training in plainchant in Rouen occurred in the context of the Solesmes movement. As will be apparent, this training was of paramount importance for Duruflé’s entire compositional career.

At age 17 Duruflé moved to Paris where he studied organ privately with Charles Tournemire, the organist at Sainte Clotilde, then with Louis Vierne at Notre Dame Cathedral, where he soon became Vierne’s assistant. A year later he entered Eugène Gigout’s organ class at the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied harmony and composition as well. (Among his colleagues in Paul Dukas’s harmony class was Olivier Messiaen, another composer whose sacred works would make an impact in the 20th century.) He distinguished himself with five “first prizes”, including in organ and composition, and other awards. By 1930 he was organist of the church of Sainte Étienne du Mont, and in 1943 became professor of harmony at the Conservatoire, and also taught organ there. He established himself as a superb organist as well as a teacher and composer. He became widely recognized in these spheres, even serving as the soloist for the premiere of the Organ Concerto by his contemporary, Francis Poulenc, in 1939.

Among Duruflé’s students was a brilliant organist, Marie-Madeleine Chevalier, whom he married in 1955. Maurice, and later he and Marie-Madeleine, had a highly successful concert career, travelling to England, Europe, Russia, and North Africa to give organ recitals. During five tours of North America Maurice conducted his increasingly popular Requiem, and he and Marie-Madeleine performed organ works to great acclaim. However, in 1975 the Duruflés were seriously injured in an automobile accident which ended Maurice’s concert career and limited Marie-Madeleine’s for a time; she recovered well enough that, after Maurice’s death in 1986, she was able to undertake successful tours and return again to the United States to perform and teach. Deteriorating health resulting from the auto accident increasingly weakened her, however, and she died in 1999.

Maurice Duruflé’s compositions are not numerous, but they are held in great esteem. The gem among them is the Requiem, Op. 9, dedicated to his father; it was given both a radio and a concert premiere in 1949 and quickly became a worldwide favorite. As mentioned earlier, performing plainchant in the Solesmes manner became as fundamental as breathing in Duruflé’s work as a church musician; it was a key ingredient in his compositional style. Just after his father’s death, he was working on a suite of organ pieces based on the plainchant of the Requiem Mass when the publisher Durand commissioned what became his Requiem. The completed work is for a mixed four-voice choir with soprano and baritone soloists (or choir section) and full orchestra; Duruflé also prepared a version with a reduced orchestra and organ accompaniment, as well as a version for organ alone. This evening’s performance uses organ and a reduced orchestra consisting of strings, timpani, three trumpets, and harp.

Duruflé’s Requiem is structured with the same movements as Fauré’s Requiem of some 50 years earlier, and has the same sense of peace and calm as Fauré’s. Both omit the doom-threatening “Dies irae” that is so strongly to the fore in both Mozart’s and Verdi’s Requiems, but both Fauré and Duruflé introduce turmoil in the “Libera me” movement. But, as he said himself, Duruflé’s work is not dependent on Fauré’s, for unlike Fauré, Duruflé constructed his movements on the liturgical chants that can be found in the Liber Usualis. The chants—and plainchant performing style—are integral to and recognizable in Duruflé’s work; he said he sought to “reconcile” the plainchant rhythms with the “exigencies” of modern metrical beats. However, the chants are not slavishly employed. They occasionally appear in different pitch ranges throughout a movement, suggesting traditional modulation techniques between sections; they are sung in chant-like unisons, or harmonized in the choral voices, or form the subject of a fugue section, as in the Kyrie. There are also occasional departures from plainchant. Nevertheless, Duruflé’s melodies live primarily in plainchant, and he created an instrumental accompaniment that supports the modality and free-flowing lines of these melodies. The harmonic language of the Requiem is quite mixed, at turns using the old medieval church modes or the classical major/minor tonal system. (Those interested should devour Jeffrey Reynolds’s analysis in “On Clouds of Incense”.) Harmonies are built of extended and often unresolved chords, a style Duruflé absorbed from Debussy’s music. Perhaps the most amazing effect appears at the very last chord, a gentle reminder of the meaning of the text.

Personal Afterword: It has been a rare treat to talk with Karen Holtkamp, of the Trinity community, about her own experiences with Maurice and Marie-Madeleine Duruflé. Her stories and comments allow us a special glimpse of the two.

Before she was married to Walter Holtkamp, Karen McFarlane became the Duruflés’ agent after the death in 1976 of their original agent, Lilian Murtagh. She has vivid and fond memories of her long association with both Maurice and Marie-Madeleine. Mrs. Holtkamp enjoyed the Duruflés tremendously, saying that they were fun to be with and had a very happy relationship. She described Marie-Madeleine as having an outgoing personality and a rich sense of humor, complementing Maurice’s quieter, more introspective personality.

As a virtuoso organist, though, Marie-Madeleine knew her own mind when it came to her performing. Visiting the Duruflés in their small Paris apartment, Mrs. Holtkamp was treated to Maurice’s performance of a Bach chorale prelude on their small pipe-organ. Then Marie-Madeleine performed Maurice’s “Fugue on Alain”. While she was playing, Maurice reached over and changed his wife’s registration. Marie-Madeleine changed it back. Again Maurice changed it, and Marie-Madeleine changed it back. The registration argument continued through the piece, much to Mrs. Holtkamp’s amusement.

Marie-Madeleine also adored cats. Mrs. Holtkamp recalls that in 1969, having just flown in to New York from Paris, the Duruflés were met by Fred Swann, organist at the Riverside Church. Fred later told Karen that almost the first thing Marie-Madeleine did was to ask after Karen’s cat Alleluya. Fred had to tell her that Alleluya was “defunct”. Turning to her husband, Marie-Madeleine exclaimed, “Oh, Maurice, you must write un petit requiem pour Alleluya!”

Our thanks to Mrs. Holtkamp for sharing these memories.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2014

MISERERE (Psalm 51)

(Translation from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer)

1 Have mercy upon me, O God, after thy great goodness,

2 according to the multitude of thy mercies do away mine offences.

3 Wash me throughly from my wickedness: and cleanse me from my sin.

4 For I acknowledge my faults: and my sin is ever before me.

5 Against thee only have I sinned, and done this evil in thy sight: that thou mightest be justified in thy saying, and clear when thou art judged.

6 Behold, I was shapen in wickedness: and in sin hath my mother conceived me.

7 But lo, thou requirest truth in the inward parts: and shalt make me to understand wisdom secretly.

8 Thou shalt purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean: thou shalt wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

9 Thou shalt make me hear of joy and gladness: that the bones which thou hast broken may rejoice.

10 Turn thy face from my sins: and put out all my misdeeds.

11 Make me a clean heart, O God: and renew a right spirit within me.

12 Cast me not away from thy presence: and take not thy holy Spirit from me.

13 O give me the comfort of thy help again: and stablish me with thy free Spirit.

14 Then shall I teach thy ways unto the wicked: and sinners shall be converted unto thee.

15 Deliver me from blood-guiltiness, O God, thou that art the God of my health: and my tongue shall sing of thy righteousness.

16 Thou shalt open my lips, O Lord: and my mouth shall shew thy praise.

17 For thou desirest no sacrifice, else would I give it thee: but thou delightest not in burnt-offerings.

18 The sacrifice of God is a troubled spirit: a broken and contrite heart, O God, shalt thou not despise.

19 O be favourable and gracious unto Sion: build thou the walls of Jerusalem.

20 Then shalt thou be pleased with the sacrifice of righteousness, with the burnt-offerings and oblations: then shall they offer young bullocks upon thine altar.

(Translation from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer)

1 Have mercy upon me, O God, after thy great goodness,

2 according to the multitude of thy mercies do away mine offences.

3 Wash me throughly from my wickedness: and cleanse me from my sin.

4 For I acknowledge my faults: and my sin is ever before me.

5 Against thee only have I sinned, and done this evil in thy sight: that thou mightest be justified in thy saying, and clear when thou art judged.

6 Behold, I was shapen in wickedness: and in sin hath my mother conceived me.

7 But lo, thou requirest truth in the inward parts: and shalt make me to understand wisdom secretly.

8 Thou shalt purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean: thou shalt wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

9 Thou shalt make me hear of joy and gladness: that the bones which thou hast broken may rejoice.

10 Turn thy face from my sins: and put out all my misdeeds.

11 Make me a clean heart, O God: and renew a right spirit within me.

12 Cast me not away from thy presence: and take not thy holy Spirit from me.

13 O give me the comfort of thy help again: and stablish me with thy free Spirit.

14 Then shall I teach thy ways unto the wicked: and sinners shall be converted unto thee.

15 Deliver me from blood-guiltiness, O God, thou that art the God of my health: and my tongue shall sing of thy righteousness.

16 Thou shalt open my lips, O Lord: and my mouth shall shew thy praise.

17 For thou desirest no sacrifice, else would I give it thee: but thou delightest not in burnt-offerings.

18 The sacrifice of God is a troubled spirit: a broken and contrite heart, O God, shalt thou not despise.

19 O be favourable and gracious unto Sion: build thou the walls of Jerusalem.

20 Then shalt thou be pleased with the sacrifice of righteousness, with the burnt-offerings and oblations: then shall they offer young bullocks upon thine altar.

QUATRE MOTETS POUR UN TEMPS DE PÉNITENCE

I. Timor et Tremor

Fear and trembling have come over me, and darkness has fallen on me. Have mercy on me, Lord, have mercy, for my soul trusts in you. God, hear my prayer, for you are my refuge and my strong advocate. Lord, I have called upon you; do not destroy me.

II. Vinea mea electa

My chosen vineyard, I planted you; why have you changed into bitterness so as to crucify me and release Barabbas? I hedged (protected) you, and removed stones from around you, and built a watch tower.

III. Tenebrae factae sunt

It became dark when they crucified Jesus of Judea. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, My God, why have you forsaken me? And bowing his head he gave out his spirit. Exclaiming in a loud voice, Jesus said, Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.

IV. Tristis est anima mea

My soul is sorrowing to death. Stay here, and watch with me. Soon you will see a crowd which will surround me. You will take flight, and I will go to be sacrificed for you. Behold, the hour is near and the son of man will be given into the hands of sinners.

I. Timor et Tremor

Fear and trembling have come over me, and darkness has fallen on me. Have mercy on me, Lord, have mercy, for my soul trusts in you. God, hear my prayer, for you are my refuge and my strong advocate. Lord, I have called upon you; do not destroy me.

II. Vinea mea electa

My chosen vineyard, I planted you; why have you changed into bitterness so as to crucify me and release Barabbas? I hedged (protected) you, and removed stones from around you, and built a watch tower.

III. Tenebrae factae sunt

It became dark when they crucified Jesus of Judea. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, My God, why have you forsaken me? And bowing his head he gave out his spirit. Exclaiming in a loud voice, Jesus said, Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.

IV. Tristis est anima mea

My soul is sorrowing to death. Stay here, and watch with me. Soon you will see a crowd which will surround me. You will take flight, and I will go to be sacrificed for you. Behold, the hour is near and the son of man will be given into the hands of sinners.

DURUFLÉ’S REQUIEM

I. Introit: Requiem Aeternam

Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

A hymn to you is fitting, O God, in Sion, and to you offerings are rendered in Jerusalem.

II. Kyrie Eleison

Lord, have mercy upon us; Christ, have mercy upon us; Lord, have mercy upon us.

III. Offertory: Domine Jesu Christe

O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, deliver the souls of all the faithful departed from infernal suffering, and from the deep abyss; deliver them from the lion’s mouth, that the underworld not devour them, that they not sink into darkness. But let the standard-bearer Saint Michael represent them in holy light, as once you promised Abraham and his seed. Sacrifices and prayers of praise we offer you, Lord; receive them for those we remember today; cause them, Lord, to cross over from death to life.

IV. Sanctus

Holy, holy, holy Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.

V. Pie Jesu (from the Sequence)

Holy Lord Jesus, give them rest. Give them eternal rest.

VI. Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, give them eternal rest.

VII. Communion: Lux Aeterna

Lord, may eternal light shine on them, with your saints in eternity, for you are righteous. Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

VIII. Responsory after Absolution (Burial Service): Libera me

Lord, deliver me from eternal death in that terrible day, when the heavens and earth are moved. I stand trembling, and I will be afraid until judgment will come and the wrath will have come, when the heavens and earth shall have been moved, when you will come to judge the world by fire; that day, the day of wrath, of calamity and misery, the great and intensely bitter day, when the heavens and earth shall be moved. Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

IX. Antiphon (Burial Service): In Paradisum

May the angels lead you into Paradise; may the martyrs receive you at your arrival and lead you into the holy city Jerusalem. May the choir of angels receive you, and may you, with the one-time pauper Lazarus, have eternal rest.

I. Introit: Requiem Aeternam

Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

A hymn to you is fitting, O God, in Sion, and to you offerings are rendered in Jerusalem.

II. Kyrie Eleison

Lord, have mercy upon us; Christ, have mercy upon us; Lord, have mercy upon us.

III. Offertory: Domine Jesu Christe

O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, deliver the souls of all the faithful departed from infernal suffering, and from the deep abyss; deliver them from the lion’s mouth, that the underworld not devour them, that they not sink into darkness. But let the standard-bearer Saint Michael represent them in holy light, as once you promised Abraham and his seed. Sacrifices and prayers of praise we offer you, Lord; receive them for those we remember today; cause them, Lord, to cross over from death to life.

IV. Sanctus

Holy, holy, holy Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.

V. Pie Jesu (from the Sequence)

Holy Lord Jesus, give them rest. Give them eternal rest.

VI. Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, give them eternal rest.

VII. Communion: Lux Aeterna

Lord, may eternal light shine on them, with your saints in eternity, for you are righteous. Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

VIII. Responsory after Absolution (Burial Service): Libera me

Lord, deliver me from eternal death in that terrible day, when the heavens and earth are moved. I stand trembling, and I will be afraid until judgment will come and the wrath will have come, when the heavens and earth shall have been moved, when you will come to judge the world by fire; that day, the day of wrath, of calamity and misery, the great and intensely bitter day, when the heavens and earth shall be moved. Give them eternal rest, Lord, and may perpetual light shine on them.

IX. Antiphon (Burial Service): In Paradisum

May the angels lead you into Paradise; may the martyrs receive you at your arrival and lead you into the holy city Jerusalem. May the choir of angels receive you, and may you, with the one-time pauper Lazarus, have eternal rest.

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.