- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

HANDEL: CHRISTMAS PORTION OF MESSIAH

On Hearing the "Christmas" Portion of Handel's Messiah

by Judith Eckelmeyer

It’s late November or early December.

You’re looking through listings of upcoming concerts and broadcasts and browsing through CDs in the stores. What work appears time and time again?

You’re looking through listings of upcoming concerts and broadcasts and browsing through CDs in the stores. What work appears time and time again?

Without question, it’s Messiah, George Frideric Handel’s incomparable oratorio, which has become the signal work of the Christmas season for millions of people the world over. In fact, Messiah is most likely to be the one of Handel’s many compositions that you know or know about, perhaps primarily through the magnificent “Hallelujah” chorus.

In the case of Messiah, the public’s familiarity is a tribute to Handel’s success at communicating through his music. It was so in his own lifetime, and it is so today. A foundation for understanding that communication is offered in the following sections, “Handel, England, and Oratorio” and “About Messiah”, and a more detailed examination of Handel’s remarkable musical language is presented in the section “Hearing the Christmas portion of Messiah”.

Handel, England, and Oratorio

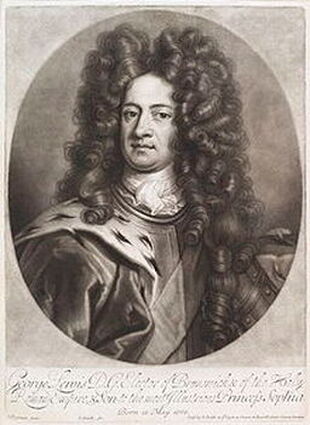

Handel, that remarkable composer of so much English music, was born in Halle, then in Saxony, in 1685.

He received his musical training there and in Hamburg before journeying to Italy early in 1707 to expand his experience. For the three years he was there, Handel absorbed the style that had made Italy the premiere center of Baroque composition (despite France’s rivalry). Returning to Germany, he accepted the appointment to serve the Elector of Hanover, George. During this period of service, Handel visited England twice, earning an early reputation there as a master of the contemporary style.

So great was his success that no less a personage than Queen Anne provided him with an annual pension. Understandably, Handel found England a congenial place and overstayed his leave from the German court.

At the death of Queen Anne in 1714, none other than George of Hanover, to whom Handel was still obligated, succeeded to the throne of England. The rapprochement between Handel and King George I took more than a year, but in the end the king maintained Handel in his service and even doubled the pension that Anne had previously bestowed.

So it was that Handel had been creating music in and for England for nearly 30 years before he wrote Messiah in 1741. He had devoted a good portion of his career to composing operas in the Italian style to entertain the social elite at theaters which he directed in London. He had also composed many choral works for the nobility, for occasions such as coronations, entertainments, state celebrations and funerals, and instrumental music for both court and church. And he had already ventured into the sphere of the oratorio with considerable success, particularly after Pepusch and Gay’s Beggar’s Opera in 1728 undercut the popularity of Italian opera with its parody of the opera seria and its use of a libretto entirely in English.

However, Handel refused to let the popular taste of the day dictate his compositional style. As a result of the changing public taste, along with production problems such as outright brawling between rival singers and increasing financial demands by the singers, he saw his opera company decline and finally fall into bankruptcy in 1737. He also suffered occasional attacks of paralysis which weakened him, interrupted his work, and led him to return to Germany for a time to recover his health.

When he returned to England, Handel’s focus shifted almost entirely from the opera to the oratorio. Certainly this made sense financially. He could draw on his compositional skill without the expenses of theater machinery, props, costumes, and drama rehearsals, since oratorio, unlike opera, was not a staged work.

Handel’s oratorios follow the tradition, established early in the seventeenth century, of treating serious subject matter from respected poets such as Milton or themes from the scripture, suitable for public presentation in penitential seasons when secular theater was deemed inappropriate for a Christian society. Most of his oratorios were stories from the Hebrew scriptures or the history of the Jewish people: Esther, Judas Maccabeus, the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt, Joseph and his brothers, Samson, and Jephtha, for example. However, he treated a more abstract subject in his Triumph of Time and Truth and a Greek myth in Herakles.

Handel’s oratorios follow the tradition, established early in the seventeenth century, of treating serious subject matter from respected poets such as Milton or themes from the scripture, suitable for public presentation in penitential seasons when secular theater was deemed inappropriate for a Christian society. Most of his oratorios were stories from the Hebrew scriptures or the history of the Jewish people: Esther, Judas Maccabeus, the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt, Joseph and his brothers, Samson, and Jephtha, for example. However, he treated a more abstract subject in his Triumph of Time and Truth and a Greek myth in Herakles.

|

Handel's "The Triumph of Time and Truth"

Sophie Bevan, Mary Bevan, William Berger, Ed Lyon, Tim Mead, Ludus Baroque Chorus | Ludus Baroque Chamber Orchestra, Richard Neville-Towle |

Handel's "Hercules"

Anne Sofie von Otter, David Daniels, Gidon Saks, Richard Croft, Lynne Dawson Les Musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkowski |

About Messiah

Messiah is a unique oratorio, for it is neither history nor dramatic tale nor philosophy. All of its text is scripture, from both Old and New Testaments, selected and sequenced by Charles Jennens, a librettist with whom Handel had collaborated previously. Its subject is the Anointed One, the Expected One, the promised royal and spiritual leader of the Jewish people. A peculiar feature of the texts which Jennens selected, however, is that in only one instance is the name Jesus cited, and that is very near the end of the oratorio. This opens the oratorio to a new role: a reflection or contemplation of the nature of the Anointed One rather than a celebration of a particular named figure.

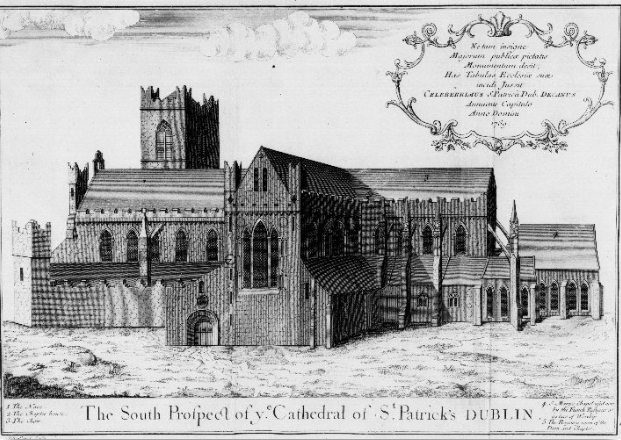

It is the abstraction of Messiah’s text that may in the long run have made it possible for Handel to offer this oratorio during Lent in a secular setting–a theater in Dublin–to raise money for several charitable institutions.

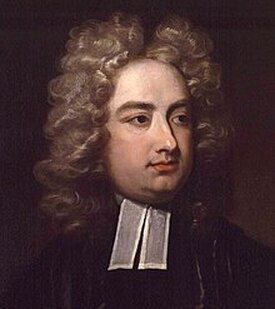

Even so, Jonathan Swift, the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, considered the performance of sacred text outside a sacred setting so abominable that he published a notice forbidding any church related person to participate in any way, or even attend any performance of the work, on pain of punishment by the church. Swift must have relented in the end, though, because singers from the cathedral choirs appeared in the premiere performance on April 13, 1742.

Messiah continued to be a favorite in Handel’s time. Different performances in different locations required the composer to prepare new arias or recast some of the existing music for different singers with different voice ranges. None of these changes dampened the public’s enthusiasm for the work. In fact, if anything, Messiah transcended its time so successfully that composers like Mozart and any number of conductors adapted it for performances in their own day.

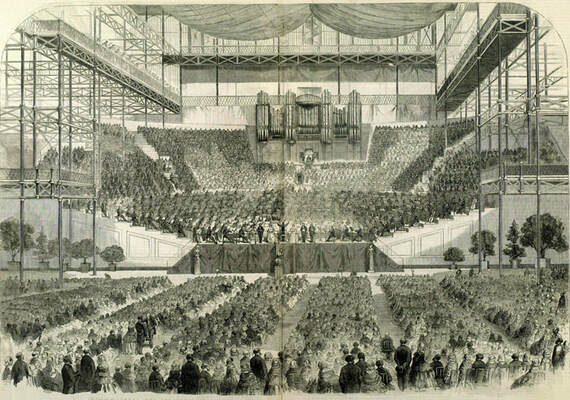

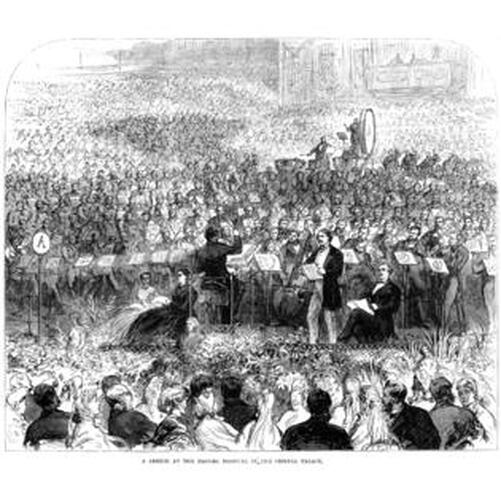

It’s safe to say that Handel would barely recognize his work in some of those adaptations: ponderous tempos that accommodated a chorus of a thousand singers; massive reorchestrations for large ensembles of modern instruments; wholly un-baroque performance style for the singers and the instrumentalists; and of course no consistent pattern for the choice of arias and choruses. Yet in spite of how musicians and adoring fans have encountered it over the centuries, Messiah remains vitally alive in the music scene and the consciousness of our culture today.

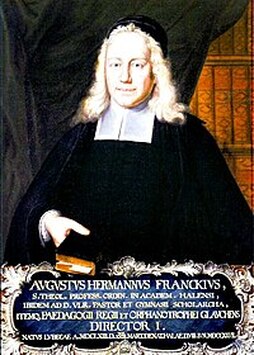

I think the key to Messiah’s perennial appeal lies in Handel’s genius at communicating meaning through his music. A devout man, he felt he was divinely inspired and even saw God when setting the text. His upbringing in a strongly Lutheran family in the Saxon city of Halle, the center of Pietistic reform, and his attendance at Halle University as a seventeen-year-old, while its Pietist founder August Hermann Francke was fully active there, may well have made it possible for him to experience the Hertzensreligion (religion in the heart), sensitizing him to the emotional power of the Bible.[1] However, promulgation of religious dogma was evidently not his aim in composing Messiah. Rather, he saw beyond the surface of the texts which Jennens selected to the human experience conveyed in them. The texts create a framework of topically related events which Handel’s music clothes in an aural analogy of peace, hope, joy, confusion, confidence, suffering, and triumph.

How can we perceive Handel’s “language” more clearly today or enhance our encounter with the rich images he brought to this oratorio? Perhaps we will benefit from a short walk alongside the music, as if in a nature reserve, examining some details as they occur in the work. We will be dealing with compositional devices such as word painting, walking bass, counterpoint and homophony, hammer strokes, dance idioms, uses of harmony and chromaticism, as well as baroque conventions of fugue, recitative, aria (here called “air”), and chorus. (The definitions for these terms can be accessed quickly if desired in the course of this essay so the flow of the discussion will not be interrupted.) These devices were common coin for Baroque-era composers, who saw their art as an extension of spoken rhetoric by which they used certain conventions to convey meaning in music (the so-called “doctrine of affects”) and move the emotions of the audience. These details are usually lost on listeners today. Our consideration of Handel’s music will explore some of these details to reconfigure our imagination to his “language” and hear his “take” on the text of Part I, the so-called Christmas portion, and the “Hallelujah” chorus. There will be references to the critical score published by the Georg-Friedrich-Händel-Gesellschaft, Bärenreiter, Kassel, 1965. The musical excerpts are from the 1992 recording by the Boston Baroque Orchestra and Chorus, directed by Martin Pearlman (Telarc CD-89322). Note: Boston Baroque received a Grammy nomination for Best Performance of a Choral Work and was named Best Messiah recording of all time by Classic CD magazine in 2010.

Hearing the Christmas portion of Messiah

Jennens and Handel organized Messiah in three parts analoqous to acts in an opera. The first concerns prophecies about the Anointed One, his birth, and his life and ministry on earth. The second deals with his suffering, death and resurrection, the promulgation of his message, the opposition to it, and the final triumph of God. The third tells of the life to come, victory over death, and God’s eternal glory.

Within each part Jennens gathered his texts into smaller groups, analogous to scenes, of two, three or four movements which work out the progress of an idea or theme. The topics of these sets, which he identified in his workbook, will be included in the relevant sections in the following discussion. Handel must have recognized these groupings, for he set individual numbers (in the version of the Gesellschaft score) in related keys within sets that parallel Jennens’ arrangement. I see the Overture as connected to the opening tenor recitative and place it within Jennens’ first grouping. Also, Jennens had not accounted for Handel’s inclusion of the Pifa, or pastoral interlude, prior to the angel’s announcement to the shepherds; I include that within the fourth set or scene.

Within each part Jennens gathered his texts into smaller groups, analogous to scenes, of two, three or four movements which work out the progress of an idea or theme. The topics of these sets, which he identified in his workbook, will be included in the relevant sections in the following discussion. Handel must have recognized these groupings, for he set individual numbers (in the version of the Gesellschaft score) in related keys within sets that parallel Jennens’ arrangement. I see the Overture as connected to the opening tenor recitative and place it within Jennens’ first grouping. Also, Jennens had not accounted for Handel’s inclusion of the Pifa, or pastoral interlude, prior to the angel’s announcement to the shepherds; I include that within the fourth set or scene.

PART I

[Set 1: Overture (E minor), tenor accompanied recitative and air (E major), chorus (A major); God’s people in tribulation, a promise of comfort and of the coming glory of God]

[Jennens: The prophecy of Salvation]

[Set 1: Overture (E minor), tenor accompanied recitative and air (E major), chorus (A major); God’s people in tribulation, a promise of comfort and of the coming glory of God]

[Jennens: The prophecy of Salvation]

HANDEL'S MESSIAH OVERTURE

As he would with any opera, Handel created a Sinfonia–an overture–for this oratorio. It is in the French style, a tradition for works of a serious nature. Its orchestration is quite simple: two oboes, violins I and II, violas and continuo consisting of keyboard, cello, violone, and bassoon.[2]

In Handel’s E-minor music a near-tragic picture emerges. The opening part, marked Grave, is homophonic (chordal) in a rhythm of severely differentiated note values (long and very short). It contains many surprising dissonances. The great tension presented here is not resolved in the ensuing faster polyphonic section, where Handel gives us a long, energized fugue subject, still in minor. This theme technically spans an octave, but works primarily in only a sixth, and concentrates in an even smaller part of that range. One might imagine a struggle in an enclosed space. Farther along in this section, rising sequences try in another way to break loose from narrow confines, only to fall downward again. Rather than longed-for release from frantic struggle, the conclusion of the sinfonia is a rather abrupt cadence confirming E minor

In Handel’s E-minor music a near-tragic picture emerges. The opening part, marked Grave, is homophonic (chordal) in a rhythm of severely differentiated note values (long and very short). It contains many surprising dissonances. The great tension presented here is not resolved in the ensuing faster polyphonic section, where Handel gives us a long, energized fugue subject, still in minor. This theme technically spans an octave, but works primarily in only a sixth, and concentrates in an even smaller part of that range. One might imagine a struggle in an enclosed space. Farther along in this section, rising sequences try in another way to break loose from narrow confines, only to fall downward again. Rather than longed-for release from frantic struggle, the conclusion of the sinfonia is a rather abrupt cadence confirming E minor

Handel's "Messiah" Sinfonia

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH ACCOMPAGNATO (ACCOMPANIED RECITATIVE) (TENOR)

Comfort ye, my people, saith your God. Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and

cry unto her that her warfare is accomplished, that her iniquity is pardoned.

The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness: Prepare ye the way

of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Gently pulsating E-Major chords in the strings[3] contrast greatly with the conclusion of the Overture. Like a heart beat, they calm and soothe. Handel marked the short introduction Larghetto e piano. The effect is one of great intimacy. The contrast between this moment and the tense, driven Overture is vivid and moving. The tenor enters without accompaniment: “Comfort ye.” Then, in one of the most beatific moments in music, over the pulsing full string ensemble, the tenor soloist sings a graciously descending phrase that offers a message of comfort to God’s distressed and war-torn people. Each statement of the “Comfort ye” passage changes slightly, but always moves downward in a pacifying gesture. By contrast, with each statement of “Saith your God”, the melody rises upward to a point of rest (a seeming tonic pitch), strong and confident. The next phrase is longer and amplifies the gesture of the comfort message. At the words “and cry...”, the tenor is again unaccompanied, and the melody leaps a full octave upward, a voice raised to be heard by Jerusalem: her warring is over. The first statement of “her iniquity” is sung to an upward leap of an augmented fourth, a tritone, from medieval times called the “devil in music”; the answering “...is pardoned” settles on a consonant major chord with a palpable release of tension.

Following this lyrical opening, the tenor issues a bold proclamation with an attention-getting fanfare. The accompaniment is reduced to simple chords in the solo string group, so the tenor is a lone voice, a prophet “crying in the wilderness”: “Prepare the way of the Lord.....” Handel’s use of the tenor at this moment is also reminiscent of the Evangelist’s role in Bach’s settings of the Passion story from the gospels of Matthew and John; he is a kind of master of ceremonies, directing our attention to the prophecy in the following aria.

Following this lyrical opening, the tenor issues a bold proclamation with an attention-getting fanfare. The accompaniment is reduced to simple chords in the solo string group, so the tenor is a lone voice, a prophet “crying in the wilderness”: “Prepare the way of the Lord.....” Handel’s use of the tenor at this moment is also reminiscent of the Evangelist’s role in Bach’s settings of the Passion story from the gospels of Matthew and John; he is a kind of master of ceremonies, directing our attention to the prophecy in the following aria.

Handel's "Messiah: Comfort ye, my people" Tenor Recitative

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH AIR (TENOR)

Ev’ry valley shall be exalted, and ev’ry mountain and hill made low,

the crooked straight and the rough places plain.

Word painting is particularly important in this aria. It helps us imagine the radical changes which will make possible a road to God. Handel paints the word “exalted” with a melody figure in a rising sequence. (I am put in mind of a pneumatic jack of some sort, driven by the air of the singer’s voice.) He repeats this device several times through the aria. “Mountains” are on higher pitches than “hills”, and the word “low” is indeed at the low pitch in the phrase. “Crooked” is realized first by quickly alternating pitches and later by a wide-ranging melody with big leaps, suggesting a path over incredibly rough terrain. This jaggedness is “made plain” by interrupting the “crooked” figure with long notes on one pitch, then descending gradually by scale steps.

Handel's "Messiah: Every valley shall be exalted" Tenor Air

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed. And all flesh shall see it together,

for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.

The orchestra introduces the chorus’s opening theme, which consists of two musical phrases presenting the first sentence of text. The chorus alto section is the first to report the “glory of the Lord.” The full chorus echoes, then the musical phrases are separated, and each becomes the object of various treatments in one or two voices at a time. It takes a while for the glory of God to appear in its entirety in the combined chorus and orchestra. “And all flesh shall see it together” receives similar treatment. However, as this text passage comes toward its close, basses and tenors, in unison, declaim “for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it” on a pedal tone beneath the sopranos and altos. In this moment the declamation is not particularly overwhelming, but it sets the precedent for what will happen as the movement progresses.

Repetitions of the first two ideas next occur in both chordal and contrapuntal manner. Fragments of “and all flesh” occur sequentially in the three lower voices; one wonders if this speaks to the lower condition of humanity which will finally see the Lord’s glory. Full choral statements of “the glory of the Lord” increasingly come “together.” The declaimed text, “for the mouth of the Lord...”, begins to appear in each of the choral parts in company with the other parts revealing the “glory.” In the final section, the sopranos present the opening melody in its highest range, so the “glory of the Lord” rises to its utmost glowing peak on a high A. By now the chorus is involved as a whole. The last moments combine simultaneous fast and slow statements of the declamation and, after a pause, a grand adagio plagal (“amen”) cadence: “hath spoken it.”

Repetitions of the first two ideas next occur in both chordal and contrapuntal manner. Fragments of “and all flesh” occur sequentially in the three lower voices; one wonders if this speaks to the lower condition of humanity which will finally see the Lord’s glory. Full choral statements of “the glory of the Lord” increasingly come “together.” The declaimed text, “for the mouth of the Lord...”, begins to appear in each of the choral parts in company with the other parts revealing the “glory.” In the final section, the sopranos present the opening melody in its highest range, so the “glory of the Lord” rises to its utmost glowing peak on a high A. By now the chorus is involved as a whole. The last moments combine simultaneous fast and slow statements of the declamation and, after a pause, a grand adagio plagal (“amen”) cadence: “hath spoken it.”

Handel's "Messiah: And the glory of the Lord" Chorus

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

[Set 2: Bass accompanied recitative, alto air (D minor), chorus (G minor); the purification of the people of God]

[Jennens: The prophecy of the coming of Messiah and the question...of what this may portend for the world.]

HANDEL'S MESSIAH ACCOMPANIED RECITATIVE (BASS)

Thus saith the Lord of Hosts: Yet once, a little while, and I will shake

the heav’ns and the earth, the sea and the dry land, and I will shake all nations;

and the desire of all nations shall come. The Lord, whom ye seek shall suddenly

come to his temple; e’en the messenger of the Covenant, whom ye delight in:

behold, He shall come, saith the Lord of Hosts.

A loud dotted-rhythm fanfare rises in the solo strings, a regal preparation for the word of the Lord. It’s in the minor; it portends some serious event–as it should, since this is the beginning of a purification of God’s people. At the fanfare’s culmination, the bass sings the imposing announcement using the downward form of the fanfare, declaiming an imperious statement from God. God’s intent to shake all of creation appears in a rising flurry of sixteenth notes. Although the “heav’ns” are higher than the “earth”, the sea is also higher than the dry land–a tsunami of sorts. The shaking idea rattles throughout recitative either in the vocal line or in the accompaniment. The “desire” of the nations trembles upward to its arrival point. The last long sentence is more openly declaimed by the voice with only reduced accompaniment punctuation, which preserves the regal dotted rhythm of the opening string fanfare.

Handel's "Messiah: Thus saith the Lord" Bass Recitative

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH AIR (ALTO)

But who may abide the day of His coming, and who shall stand when He appeareth?

For He is like a refiner’s fire.

In spite of the frequent, even usual, performance of this aria by a bass, it is likely that not Handel but Mozart, through Vincent Novello’s printing of the score, was responsible for handing it down to us in its complete form for the bass.[4] Handel wrote an early abbreviated version of it for bass, without the fast section, and then two other versions (in different keys) including both slow (Larghetto) and fast (Prestissimo) sections, for male alto (the castrato Gaetano Guadagni) and for soprano. In the Handel Gesellschaft edition, the accompanied recitative “Thus saith the Lord” is for bass and this air is for alto. Regardless of the range, Handel’s setting of the text is stunning.

The triple meter and minuet--almost barcarole--rhythm that begins the air is deceptive, lulling the unwary into a false sense of peace. The gentle rocking is reminiscent of the image of the oldster in the rocking chair, bemoaning the “bad times” when considering who will survive the winnowing at the day of the Lord’s coming. The reason for the worry becomes obvious in the Prestissimo section: God is a refiner’s fire which burns away the impurities in great heat. The repeated 16th-note pattern in the accompaniment shimmers like glowing coals; then the pitches in the strings leap by octaves, like flames being fanned in a furnace. Downward runs by the singer suggest the dross melting away in the conflagration; then upward leaps spew flame and superheated gases that are a part of the refining process. Handel’s imagery is all too vivid!

The triple meter and minuet--almost barcarole--rhythm that begins the air is deceptive, lulling the unwary into a false sense of peace. The gentle rocking is reminiscent of the image of the oldster in the rocking chair, bemoaning the “bad times” when considering who will survive the winnowing at the day of the Lord’s coming. The reason for the worry becomes obvious in the Prestissimo section: God is a refiner’s fire which burns away the impurities in great heat. The repeated 16th-note pattern in the accompaniment shimmers like glowing coals; then the pitches in the strings leap by octaves, like flames being fanned in a furnace. Downward runs by the singer suggest the dross melting away in the conflagration; then upward leaps spew flame and superheated gases that are a part of the refining process. Handel’s imagery is all too vivid!

Handel's "Messiah: Who may abide" Alto Air

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

And He shall purify the sons of Levi, that they may offer unto the Lord an offering in righteousness.

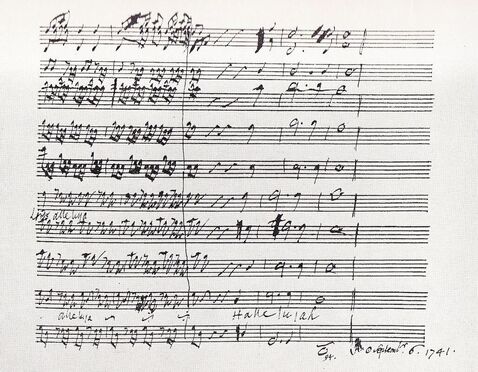

One of the great stories about Messiah is that Handel composed it in the unbelievably short time of three weeks–August 22 to September 12, 1741. A cynic knowing that Handel borrowed some of his own earlier works for this oratorio would be inclined to minimize the achievement, thinking that reusing music is a shortcut to composing new music. However, there are only four reworked numbers in the entire oratorio, and this chorus is one of them. Originally it was an Italian duet for two sopranos, as were the three other borrowings. The source of this fugue is the third movement of "Quel fior che all’alba ride", which Handel wrote earlier in the summer of 1741, about six weeks before beginning Messiah. There seems to be no connection between the text of the fugue and that of duet: “[Life’s] sunset is at dawn, and it loses its springtime in a single day.”[5]

Handel creates some interesting imagery in this chorus. A key phrase in the work is the second one that the chorus sings. It begins on a leap up to four repeated high eighth notes which occur on the words “He shall puri-....” These four notes seem like short hammer strokes. When followed by the long runs of 16th notes on the final syllable of “purify”, they suggest a shaping and further smelting of metal, continuing the idea of the refiner’s furnace from the previous air. A further “refinement” occurs when the pitches on the words “the sons of Levi” retrace the descending scale that was contained in the first part of the sentence. In other words, the music for the sons of Levi (the priestly line) is the pared-down, “purified” version of that phrase that ends with the long run of 16th notes. Finally, the entire priestly class is clarified into unmistakable chordal unity to offer “an offering in righteousness.”

Handel creates some interesting imagery in this chorus. A key phrase in the work is the second one that the chorus sings. It begins on a leap up to four repeated high eighth notes which occur on the words “He shall puri-....” These four notes seem like short hammer strokes. When followed by the long runs of 16th notes on the final syllable of “purify”, they suggest a shaping and further smelting of metal, continuing the idea of the refiner’s furnace from the previous air. A further “refinement” occurs when the pitches on the words “the sons of Levi” retrace the descending scale that was contained in the first part of the sentence. In other words, the music for the sons of Levi (the priestly line) is the pared-down, “purified” version of that phrase that ends with the long run of 16th notes. Finally, the entire priestly class is clarified into unmistakable chordal unity to offer “an offering in righteousness.”

Handel's "Messiah: He shall purify" Chorus

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

[Set 3: Alto recitative and air and chorus (D major), bass recitative and air (B minor); the promise of light to the people in darkness]

[Jennens: The prophecy of the Virgin Birth]

HANDEL'S MESSIAH RECITATIVE (ALTO)

Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son,

and shall call his name Emmanuel, “God with us.”

The complex energy of the purification scene dissipates, and the entire atmosphere softens into D major. The alto’s simple unaccompanied recitative suggests the unassuming nature of the Virgin, and its major key opens the door to a brighter prophecy that brings us closer to the birth of Messiah.

Handel's "Messiah: Behold a virgin shall conceive" Alto Recitative

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH AIR (ALTO) AND CHORUS

O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion, get thee up into the high mountain,

lift up thy voice with strength, lift it up, be not afraid; say unto the cities of Judah,

behold your God! Arise, shine; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord

is risen upon thee.

Expectation of Messiah’s presence brings great joy, which Handel casts as a sweetly flowing gigue. The first and second principal violins together play a wonderfully glimmering, dancing melody that both introduces the alto and then answers the vocal line between phrases. This violin melody appears in a high range then suddenly shifts two octaves lower; the range bifurcation suggests the high and low geography mentioned in the text: the messenger of the good news is instructed to get up “into the high mountain”, from where the proclamation may be better heard abroad. “Lift up...thy voice...with strength; lift it up...be not afraid” occurs on a rising sequence. From the pinnacle of that sequence the listener is told to “behold your God!” A long, florid, rising sequence on the word “glory” projects the far-reaching splendor of the “light” that “is come.”

The alto’s air melds into the answering chorus, taking the message fugally into each voice for a short time. Then bold homophony takes over. “Arise” is declaimed so clearly as to be a command, and “say unto the cities of Judah, Behold your God!” is a commission from the unified voices.

The alto’s air melds into the answering chorus, taking the message fugally into each voice for a short time. Then bold homophony takes over. “Arise” is declaimed so clearly as to be a command, and “say unto the cities of Judah, Behold your God!” is a commission from the unified voices.

Handel's "Messiah: O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion" Alto Air and Chorus

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH ACCOMPAGNATO (ACCOMPANIED RECITATIVE) (BASS)

For behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the people;

but the Lord shall arise upon thee, and His glory shall be seen upon thee.

And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.

Franz Joseph Haydn composed his famous portrayal of the creation of light at the beginning of his oratorio "Die Schöpfung" (The Creation) in 1797. He may well have been strongly influenced in his treatment of that moment by this recitative and the following air in Messiah, which he had heard at least in part in England and probably also in Mozart’s reorchestration earlier that decade in Vienna. This recitative in particular is one of the most vivid portrayals of the distinction between darkness and light prior to Haydn’s.

The solo violins and viola, along with continuo, open with a mysterious, close-range pulsing alternation of step-wise 16th-note pitches in B minor that opens briefly outward, only to close inward again at the minor cadence. The bassoon has joined the continuo for this introduction, darkening further the timbre of the bass line. The bass voice enters with its fanfare-like melody ominous in longer notes while the string pulsations of 16th notes surround it. Just as the bass arrives at the text “but the Lord shall arise”, the accompanying figures settle into repeated 8th notes, and suddenly in D major! The Lord’s rising is shown in a beautifully unfolding upward sequence supported by a similarly rising continuo bass below it. The Lord’s glory expands in a flowing downward line as if upon his people. Handel returns to the minor at the mention of the gentiles and kings who are still in darkness.

The solo violins and viola, along with continuo, open with a mysterious, close-range pulsing alternation of step-wise 16th-note pitches in B minor that opens briefly outward, only to close inward again at the minor cadence. The bassoon has joined the continuo for this introduction, darkening further the timbre of the bass line. The bass voice enters with its fanfare-like melody ominous in longer notes while the string pulsations of 16th notes surround it. Just as the bass arrives at the text “but the Lord shall arise”, the accompanying figures settle into repeated 8th notes, and suddenly in D major! The Lord’s rising is shown in a beautifully unfolding upward sequence supported by a similarly rising continuo bass below it. The Lord’s glory expands in a flowing downward line as if upon his people. Handel returns to the minor at the mention of the gentiles and kings who are still in darkness.

Handel's "Messiah: For behold, darkness shall cover the earth" Bass Recitative and Chorus

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH AIR (BASS)

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light. And they that dwell

in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined.

The alternating step-wise pitches are continued here, but the motion has broadened some so that each pair of notes can be perceived to a beat. The result is a “walking” pace and “walking” bass line, supporting the notion of the “people that walked....” The voice and all the instruments are moving in unison, giving this air a bleakness suggestive of a void. “Darkness” pervades the chromatic changes in the pitches of the melody as well as the very low pitches at the cadence of the first vocal phrase: one and a half octaves below middle C! (Some performers choose an alternative cadence on higher pitches here.) The murky tonality is reinforced in rising melody until the next text phrase, when the people see “a great light”; here the D-major tonality takes over. Suddenly, harmony is introduced in the accompaniment. There is a second hearing of the same text, set similarly, but in this second event the soloist’s word “light” is illuminated with harmony. This same text and harmonic progression from “dark” to “light” is given a second time. The next words center around “the shadow of death.” Now the minor key is unrelieved, and the chromaticism and strange stalking leaps continue in the accompaniment. “Death” is protracted in the voice, violas, and continuo basses. The light “shines” briefly in major but returns again to the shadowy world of death to end the air. In this moment of the prophecy there is still a great deal of darkness as the world awaits the promised birth of Messiah.

Handel's "Messiah: The people that walked in darkness" Bass Air

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

[Set 4: Chorus (G major), Pifa (C major), soprano recitatives (C major, F major, A major - F-sharp minor, D major), chorus (D major)]

[Jennens: The appearance of the Angels to the Shepherds]

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

For unto us a Child is born, unto us a Son is given: and the government

shall be upon his shoulder: and His Name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor,

The Mighty God, The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace!

It’s a toss-up as to whether this chorus belongs with the “prophecy” of the virgin birth or to the announcement of the birth to the shepherds. Its key of G major allows for both options. It could be considered the final chorus of the previous set or scene, making the Pifa the opening of this mini-scene. However, I chose to put the chorus with the fourth scene because of the present tense in the text, which I think sets up the subsequent numbers. This is another of Handel’s self-borrowings. The source is the first movement of his duet "Nò, di voi non vo’ fidarmi", from the summer of 1741. Here, too, the oratorio text seems unrelated to that of the duet: “No, I will not trust you, blind love, cruel beauty! You are goddesses who lie and flatter too much.”[6]

Handel adds two oboe parts doubling the two violin parts and a bassoon to the continuo. The dance-like rhythm suggests buoyancy and joy. Sopranos of the chorus are the first to announce the Child’s birth. Tenors respond briefly, then the sopranos go on with an extended laugh-like flourish on the word “born.” Tenors can only comment in short gasps. The reverse pattern occurs when the basses laugh with the birth and the altos gasp. The government is shown in regal dotted rhythms. Everyone calls the Child by His extraordinary titles in strong homophonic acclamation while the violins laugh and rejoice. At one point, both women’s voices gleefully raise the newborn Child, while the men comment in gasps.

Handel adds two oboe parts doubling the two violin parts and a bassoon to the continuo. The dance-like rhythm suggests buoyancy and joy. Sopranos of the chorus are the first to announce the Child’s birth. Tenors respond briefly, then the sopranos go on with an extended laugh-like flourish on the word “born.” Tenors can only comment in short gasps. The reverse pattern occurs when the basses laugh with the birth and the altos gasp. The government is shown in regal dotted rhythms. Everyone calls the Child by His extraordinary titles in strong homophonic acclamation while the violins laugh and rejoice. At one point, both women’s voices gleefully raise the newborn Child, while the men comment in gasps.

Handel's "Messiah: For unto us a Child is born" Chorus

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH PIFA

This is a moment that Charles Jennens could not have predicted, for it comes from the realm of opera, not scripture. The prophecy scenes have come to an end, a Child has been born, and the instrumental ensemble raises a curtain on a scene in the country. The term Pifa means “pipe”, as in a shepherd’s recorder or flute. Handel’s music is a siciliano, a rustic Italian dance in a lilting compound quadruple meter (quite singular in Messiah). A pedal tone provides evidence of bagpipe drones while three violins and a viola charm us with a naive melody, untutored in its awkward phrase lengths and utterly simple harmony. We are being transported to the fields where idealized sheep are being tended by nobly simple shepherds, who entertain themselves with music in the night.

Handel's "Messiah: Pifa"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH RECITATIVE (SOPRANO)

There were shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night.

The pastoral scene evoked by the Pifa is confirmed by the soprano in this dry recitative; the pedal in the continuo keeps us aware of the shepherds’ presence and their simplicity.

HANDEL'S MESSIAH ACCOMPAGNATO (ACCOMPANIED RECITATIVE) (SOPRANO)

And lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord

shone round about them, and they were sore afraid.

shone round about them, and they were sore afraid.

The accompaniment for the soprano is most interesting, for its rising 16th-note arpeggios over repeated 8th notes in the viola and continuo bass suggest the pulsing wing beats[7] of the angel; the tempo is marked Andante. The solo violins, in parallel thirds, pair nicely as wings. The continuo bass is quite high, ranging between D and F above middle C until the shepherds are reported to be afraid. The effect is one of hovering almost motionless.

Handel's "Messiah: There were shepherds/And lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH RECITATIVE (SOPRANO)

And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy,

which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David

a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.

The return to dry recitative for the angel's message allows the words to be the focal point. The first portion of the announcement is in the major mode (through “all people”), but the actual pronouncement of the birth of the Savior is in the minor. There is a subtle vulnerability, perhaps also a foreboding of the Messiah’s eventual sacrificial death, and certainly a reflection of the human condition in this harmonic shift.

Handel's "Messiah: And the angel said unto them"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH ACCOMPAGNATO (ACCOMPANIED RECITATIVE) (SOPRANO)

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heaven’ly host,

praising God, and saying,

Again, Handel uses accompanied recitative for the appearance of a "multitude" of angels. There is much more rapid activity in the violins, which are in an even higher range than with the appearance of the single angel. Now the tempo is marked Allegro. Even the narrating soprano seems more energized, for her range extends up to a high A. The word attacca at the cadence indicates that the recitative must move immediately to the following chorus.

Handel's "Messiah: And suddenly there was with the angel"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth, goodwill towards men.

This chorus is a wonderful example of Handel’s genius at communicating through music and shows the degree to which his long experience of composing operas informs this oratorio. There are three dimensions to the picture. First is the depiction of the angels’ location, changing from hovering very high above the shepherds’ head to standing right on the ground in front of them. Second is the way the message is transmitted. Third is the ambient activity in the course of the angels’ delivery of the message.

The first statement "glory to God" has the regal dotted rhythm in it, and two trumpets–symbols of royalty–join in “from afar and a little softly.” Violin activity suggests a great swarming of the heavenly host. The chorus begins from the angels’ position high above the shepherds. The vocal and instrumental parts sit up in the high range. The choral basses are not singing, and the tenors’ part lies from A below middle C to the A an octave above! The continuo bass doubles the tenors, using only the cello (omitting the violone and bassoon, which will be brought in later). A flurry of angel wings descends in the violins following the first declamation.

"Peace on earth" is on one pitch (and its octave) in longer notes, an extremely placid melodic profile. Its first occurrence is presented in the tenor and basses, doubled by all the instruments. The bass part leaps down an octave, suggesting peace bestowed from heaven above to humanity below. In every statement of this text phrase, the octave descent is present.

Following this proclamation, the angels remain hovering for a moment, then repeat “Glory to God in the highest.” As they do, there is again much fluttering in the violins. The basses are still absent, but the tenors have begun to visit a few of the lower notes more frequently, and the sopranos and altos have exchanged pitches of the opening chords, so they now sit in a more moderate range. The multitude is gradually coming closer to ground level.

A second statement of “peace on earth” has both tenor and bass falling the octave. Again, the angels “hover” for a moment.

Handel introduces "goodwill toward men" in a kind of short fugetto, suggesting that the distribution of good will is always in some way imitative. During the beginning of this section the strings and oboes double the voices, but at the cadence the 16th-note flurry begins again and continues through the third and final statement "Glory to God", until “peace on earth” is again proclaimed. This third “Glory to God” brings the angels virtually on the same plane with the shepherds. The choral basses are now providing chordal roots and the other voices are in a normal position. The orchestra employs not only trumpets and oboes, but also lower strings and bassoon. After a final “peace on earth”, “goodwill” is revisited, again beginning imitatively; then Handel has the sopranos offer and the lower three voices respond. Finally all the world is in accord in promoting goodwill together.

Lest the angels be abandoned on earth, Handel creates a wonderful coda in which the solo strings and continuo bass gradually rise upward and become increasingly invisible. A final light trill in the violins is the last flutter we perceive of the wings.

The first statement "glory to God" has the regal dotted rhythm in it, and two trumpets–symbols of royalty–join in “from afar and a little softly.” Violin activity suggests a great swarming of the heavenly host. The chorus begins from the angels’ position high above the shepherds. The vocal and instrumental parts sit up in the high range. The choral basses are not singing, and the tenors’ part lies from A below middle C to the A an octave above! The continuo bass doubles the tenors, using only the cello (omitting the violone and bassoon, which will be brought in later). A flurry of angel wings descends in the violins following the first declamation.

"Peace on earth" is on one pitch (and its octave) in longer notes, an extremely placid melodic profile. Its first occurrence is presented in the tenor and basses, doubled by all the instruments. The bass part leaps down an octave, suggesting peace bestowed from heaven above to humanity below. In every statement of this text phrase, the octave descent is present.

Following this proclamation, the angels remain hovering for a moment, then repeat “Glory to God in the highest.” As they do, there is again much fluttering in the violins. The basses are still absent, but the tenors have begun to visit a few of the lower notes more frequently, and the sopranos and altos have exchanged pitches of the opening chords, so they now sit in a more moderate range. The multitude is gradually coming closer to ground level.

A second statement of “peace on earth” has both tenor and bass falling the octave. Again, the angels “hover” for a moment.

Handel introduces "goodwill toward men" in a kind of short fugetto, suggesting that the distribution of good will is always in some way imitative. During the beginning of this section the strings and oboes double the voices, but at the cadence the 16th-note flurry begins again and continues through the third and final statement "Glory to God", until “peace on earth” is again proclaimed. This third “Glory to God” brings the angels virtually on the same plane with the shepherds. The choral basses are now providing chordal roots and the other voices are in a normal position. The orchestra employs not only trumpets and oboes, but also lower strings and bassoon. After a final “peace on earth”, “goodwill” is revisited, again beginning imitatively; then Handel has the sopranos offer and the lower three voices respond. Finally all the world is in accord in promoting goodwill together.

Lest the angels be abandoned on earth, Handel creates a wonderful coda in which the solo strings and continuo bass gradually rise upward and become increasingly invisible. A final light trill in the violins is the last flutter we perceive of the wings.

Handel's "Messiah: Glory to God"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

[Set 5: Soprano air (B-flat major), Alto recitative (D major - A minor), alto and soprano air (F major - B-flat major), chorus (B-flat major)]

[Jennens: Christ’s redemptive miracles on earth.]

HANDEL'S MESSIAH AIR (SOPRANO)

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion, shout, O daughter of Jerusalem:

behold, thy King cometh unto thee:

He is the righteous Saviour, and he shall speak peace unto the heathen.

Handel uses a modified A-B-A or da capo form for this air, truly distinguishing between the affects of the two sections. The joyous music of the opening sentiment is almost breathless at first, rising upward as it invokes a rising spirit. Subsequent settings of “rejoice” laugh and dance in longer and longer garlands of sequences. The long high note on “shout” does just that–projects outward to the daughter of Jerusalem. The King comes to Jerusalem through a vigorous descending pattern. The second section is in the relative minor. Its new mode and longer phrases in more regulated note values convey a less giddy mood, a new tone of solemnity worthy of the gravity of righteousness. Separated statements of the word “peace”, on longer notes in the melody and underlaid by a pedal tone in the bass, calm and settle the action in the music as a complete antithesis of the word “rejoice.” The air returns to the first idea, elaborating on it in a written out form rather than simply repeating it. There are longer and more diverse rejoicings and shorter, more highly energized shouts. The instrumental coda provides a further elaboration of the first section’s melody as if clearly delighted with the event.

Handel's "Messiah: Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH RECITATIVE (ALTO)

Then shall the eyes of the blind be open’d, and the ears of the deaf unstopped;

then shall the lame man leap as an hart, and the tongue of the dumb shall sing.

Interesting things happen in this brief recitative. The first three text phrases are treated in a rising sequence, as if we are to hear them with growing amazement. In the first two, there is a brief hesitation written in the score (as a rest) before the particular handicap is reversed, but with the third there is no stopping–the lame man rises up unimpeded! The final phrase is cast as an unelaborated fact. Might we assume that the following duet is the song?

Handel's "Messiah: Then shall the eyes of the blind"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH DUET (ALTO, SOPRANO)

He shall feed his flock like a shepherd, and he shall gather the lambs with his arm;

and carry them in His bosom, and gently lead those that are with young.

Come unto him, all ye that labor, come unto him that are heavy laden, and he

will give you rest. Take His yoke upon you, and learn of Him, for he is meek and

lowly of heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls.

The shepherd’s tender care of his flock brings back the pastoral motion of the Pifa, even replicating its compound quadruple meter, form, simple harmonies and long pedal notes of the drone. This is a sequential duet, the alto singing the first “verse” in F major, the soprano the second in B-flat major. The settings are virtually the same in spite of the transposition.

Handel's "Messiah: He shall feed His flock like a shepherd"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

His yoke is easy, his burden is light.

Completing Part I, this fugal chorus is reworked from the first movement of "Quel fior che all’alba ride" on the text, “That flower which smiles at dawn the sun later causes to wither, and in the evening it goes to its grave.”[8]

This is a surprising movement, short on text and ironically long on technical demand for the singers. The word “easy” lies high and is set to a protracted melisma of intricate turns on 16th notes interrupted by a hiccough--an irregularity created by a dotted 16th- and 32nd-note combination. This “easy” yoke spans more than a measure in an easy-going tempo, while the “light” burden, frequently set on a lilting rising figure, comes in short bursts. The overall motion of the music is that of dance. At the beginning of the movement voices enter alone or in pairs, but close to the end of the movement the four parts work simultaneously. Even here, though, Handel does not let the music become massy. Instead of marching to the pulse laid down by the bass and continuo, he incorporates delightful syncopations in the chorus and upper strings, throwing the weight away from the expected points of accent and lightening the motion. This wonderful movement reinforces the joyfulness of the Messiah’s good works.

This is a surprising movement, short on text and ironically long on technical demand for the singers. The word “easy” lies high and is set to a protracted melisma of intricate turns on 16th notes interrupted by a hiccough--an irregularity created by a dotted 16th- and 32nd-note combination. This “easy” yoke spans more than a measure in an easy-going tempo, while the “light” burden, frequently set on a lilting rising figure, comes in short bursts. The overall motion of the music is that of dance. At the beginning of the movement voices enter alone or in pairs, but close to the end of the movement the four parts work simultaneously. Even here, though, Handel does not let the music become massy. Instead of marching to the pulse laid down by the bass and continuo, he incorporates delightful syncopations in the chorus and upper strings, throwing the weight away from the expected points of accent and lightening the motion. This wonderful movement reinforces the joyfulness of the Messiah’s good works.

Handel's "Messiah: His yoke is easy"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

From PART II

HANDEL'S MESSIAH CHORUS

Hallelujah! For the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth. The kingdom of this world

is become the kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ; and He shall reign for ever and ever,

King of Kings, and Lord of Lords.

The impact of this most famous chorus comes in part from its expanded orchestra: besides the strings and continuo Handel included two oboes, two trumpets, and timpani. The context of this movement within the oratorio is important: it presents the final victory of God and his Messiah over those who have opposed and rejected his message toward the end of Part II. The trumpets and timpani are associated with triumphant royalty in Handel’s time. The key of D major is traditional for great victorious pieces because the Baroque high trumpet’s home key is D, so that even without the keys of the modern instrument it could contribute to a jubilee effect. Handel has given us a glimpse of God as a military king who has won over his opponents in a great war. The massive homophonic exclamations from the chorus suggest not just an adoring crowd but even a people acclaiming a newly crowned king. Similar expressions can be found in Handel’s Coronation Anthem “Zadok the Priest”, when the people cry out, “God save the king, long live the King!”

After the initial acclamations, Handel introduces a subject for constant imitation on the words “For the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.” As this theme expands through the choral voices, hallelujahs provide energy in the background. More and more activity brings the first section to a strong cadence. Then, a quieter section begins with a marvelous image. “The Kingdom of this world is become...” sits sedately in a moderately low range. But it is linked, by more than an octave leap up in sopranos, an octave leap up in the basses and big upward leaps in alto and tenor, with a musically parallel setting of “the Kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ.” The upward leap toward the heavenly realm is remembered with first notes of the bass presentation, “and He shall reign for ever....” Naturally this is further presented in all voices, the tenors and sopranos particularly reaching quite to the highest point of their range. Trumpet-like acclamations of “King of Kings” are sustained “for ever and ever” and answered by repeated hallelujahs, and the first trumpet’s hair-raising descending scale propels the sopranos’ escalating series of high, brilliant statements, “King of Kings”, reinforced by the trumpet. A period of more scattered fragments of the main themes feeds into a great homophonic conclusion of pulsating simultaneous statements “King of Kings...” and “for ever and ever...” Finally, in a drive to the last cadence, are repeated exclamations of “Hallelujah!”

After the initial acclamations, Handel introduces a subject for constant imitation on the words “For the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.” As this theme expands through the choral voices, hallelujahs provide energy in the background. More and more activity brings the first section to a strong cadence. Then, a quieter section begins with a marvelous image. “The Kingdom of this world is become...” sits sedately in a moderately low range. But it is linked, by more than an octave leap up in sopranos, an octave leap up in the basses and big upward leaps in alto and tenor, with a musically parallel setting of “the Kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ.” The upward leap toward the heavenly realm is remembered with first notes of the bass presentation, “and He shall reign for ever....” Naturally this is further presented in all voices, the tenors and sopranos particularly reaching quite to the highest point of their range. Trumpet-like acclamations of “King of Kings” are sustained “for ever and ever” and answered by repeated hallelujahs, and the first trumpet’s hair-raising descending scale propels the sopranos’ escalating series of high, brilliant statements, “King of Kings”, reinforced by the trumpet. A period of more scattered fragments of the main themes feeds into a great homophonic conclusion of pulsating simultaneous statements “King of Kings...” and “for ever and ever...” Finally, in a drive to the last cadence, are repeated exclamations of “Hallelujah!”

Handel's "Messiah: Hallelujah"

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

Boston Baroque, Martin Pearlman

Karen Clift, soprano | Catherine Robbin, mezzo-soprano | Bruce Fowler, tenor | Victor Ledbetter, baritone

ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READINGS ONLINE

The cited materials and several web sources (along with 2020 updates) have articles worth reading. Among them are these, which are especially interesting:

Teeters, Donald. “At last, Messiah”, 2004, at http://www.bostoncecilia.org/prognotes/handel-messiah.html. Program notes for The Boston Cecilia performance of the oratorio share a conductor’s viewpoint. Note: Updated link https://messiah-guide.com/analysis8.html

Thomas, Jeffrey. Messiah. Notes for the 2004-2005 season by the music director of the American Bach Soloists at http://www.americanbach.org/seasons/04-05/MessiahNotes.html give more perspective on details of the work and its history. Note: Updated link to commentary by Jeffrey Thomas https://americanbach.org/media/AboutMessiah.html

Vickers, David. Messiah, “A sacred Oratorio”, at http://gfhandel.org/messiah.htm, gives a short history of the work, lists editions and recordings, and provides a useful bibliography. Note: Updated link http://gfhandel.org/handel/messiah.html

“Messiah” at http:www.stpatrickscathedral.ie/handel’s.htm contains the text of three documents related to the first Dublin performance of the oratorio. Note: St. Patrick's Cathedral link no longer links to documents. An alternate source essay can be found at https://www.dunedin-consort.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Messiah_Extended_Notes.pdf

The cited materials and several web sources (along with 2020 updates) have articles worth reading. Among them are these, which are especially interesting:

Teeters, Donald. “At last, Messiah”, 2004, at http://www.bostoncecilia.org/prognotes/handel-messiah.html. Program notes for The Boston Cecilia performance of the oratorio share a conductor’s viewpoint. Note: Updated link https://messiah-guide.com/analysis8.html

Thomas, Jeffrey. Messiah. Notes for the 2004-2005 season by the music director of the American Bach Soloists at http://www.americanbach.org/seasons/04-05/MessiahNotes.html give more perspective on details of the work and its history. Note: Updated link to commentary by Jeffrey Thomas https://americanbach.org/media/AboutMessiah.html

Vickers, David. Messiah, “A sacred Oratorio”, at http://gfhandel.org/messiah.htm, gives a short history of the work, lists editions and recordings, and provides a useful bibliography. Note: Updated link http://gfhandel.org/handel/messiah.html

“Messiah” at http:www.stpatrickscathedral.ie/handel’s.htm contains the text of three documents related to the first Dublin performance of the oratorio. Note: St. Patrick's Cathedral link no longer links to documents. An alternate source essay can be found at https://www.dunedin-consort.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Messiah_Extended_Notes.pdf

Prepared for Music Academy Online, November 30, 2006 (revisions and updates 2020)

[1] Jennifer Payne, “Halle Pietism: Religious Compromise and Prussian Social Transformation,” htte://www.geocities.com/Athens/Aegean/7023/pietism.html?200516, August 1998 revision. An interesting essay on the religious environment in 17th-century Halle. Note: Geocities website now archived at http://www.oocities.org/athens/aegean/7023/

[2] The keyboard instrument is unspecified; harpsichord would have been the theater instrument, but organ would have been available in a church as well as harpsichord. The violone is the largest instrument in the viol family, the equivalent of today’s string bass. The bassoon is often not present in the continuo.

[3] The score specifies senza ripieno (without the full ensemble–i.e., using only a soloist from each string section); the full ensemble enters in measure five. Handel used contrasting string densities throughout the oratorio. Typically the soloists performed the introductions to airs and choruses and sometimes soft interludes between vocal phrases, and often accompanied lyrical or intricate vocal lines. The full ensemble provided forceful statements where Handel needed them.

[4] Van Camp, A Practical Guide for Performing, Teaching and Singing “Messiah” (Dayton: Roger Dean Publishing Company, 1993), 38. For a full exploration of the various version and the performances for which they were written, see Watkins Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s Messiah” (Borough Green, Kent, England: Novello and Company, Limited, 1963).

[5] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 159.

[6] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 159.

[7] Van Camp, A Practical Guide for Performing, Teaching and Singing “Messiah”, 55, tentatively suggests this image. Given the continued use of the string activity wherever the angels are present in the next recitative and the following chorus, I think Handel intended the reference.

[8] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 168-169.

[1] Jennifer Payne, “Halle Pietism: Religious Compromise and Prussian Social Transformation,” htte://www.geocities.com/Athens/Aegean/7023/pietism.html?200516, August 1998 revision. An interesting essay on the religious environment in 17th-century Halle. Note: Geocities website now archived at http://www.oocities.org/athens/aegean/7023/

[2] The keyboard instrument is unspecified; harpsichord would have been the theater instrument, but organ would have been available in a church as well as harpsichord. The violone is the largest instrument in the viol family, the equivalent of today’s string bass. The bassoon is often not present in the continuo.

[3] The score specifies senza ripieno (without the full ensemble–i.e., using only a soloist from each string section); the full ensemble enters in measure five. Handel used contrasting string densities throughout the oratorio. Typically the soloists performed the introductions to airs and choruses and sometimes soft interludes between vocal phrases, and often accompanied lyrical or intricate vocal lines. The full ensemble provided forceful statements where Handel needed them.

[4] Van Camp, A Practical Guide for Performing, Teaching and Singing “Messiah” (Dayton: Roger Dean Publishing Company, 1993), 38. For a full exploration of the various version and the performances for which they were written, see Watkins Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s Messiah” (Borough Green, Kent, England: Novello and Company, Limited, 1963).

[5] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 159.

[6] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 159.

[7] Van Camp, A Practical Guide for Performing, Teaching and Singing “Messiah”, 55, tentatively suggests this image. Given the continued use of the string activity wherever the angels are present in the next recitative and the following chorus, I think Handel intended the reference.

[8] Shaw, A textual companion to Handel’s “Messiah”, 168-169.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2006/revised 2020

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.