- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

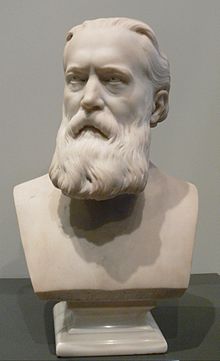

BRAHMS: A GERMAN REQUIEM

A GERMAN REQUIEM

According to Words of Holy Scripture,

for Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra [Organ ad lib.], Op. 45

An Oratorio by Johannes Brahms

According to Words of Holy Scripture,

for Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra [Organ ad lib.], Op. 45

An Oratorio by Johannes Brahms

This essay is an expanded version of the program notes by Judith Eckelmeyer for the performance of A German Requiem at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, Cleveland, Ohio, on March 29, 2013. The Trinity Cathedral Choir was directed by Todd Wilson; pianists Elizabeth Lenti and Elizabeth Di Mio performed Brahms’s 4-hand piano accompaniment.

Brahms’s Life and the Genesis of the German Requiem

Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45, of Johannes Brahms is a guide to how the yet-living mourner might embrace the event of the death of a loved one, even one’s own death. It is an apocalyptic work in the original sense of the word—a revelation: of what awaits at the end of life, and the nature of the struggle to get there and understand it.

Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45, of Johannes Brahms is a guide to how the yet-living mourner might embrace the event of the death of a loved one, even one’s own death. It is an apocalyptic work in the original sense of the word—a revelation: of what awaits at the end of life, and the nature of the struggle to get there and understand it.

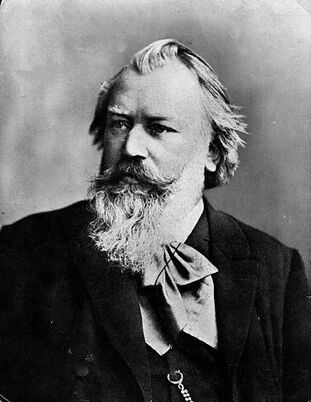

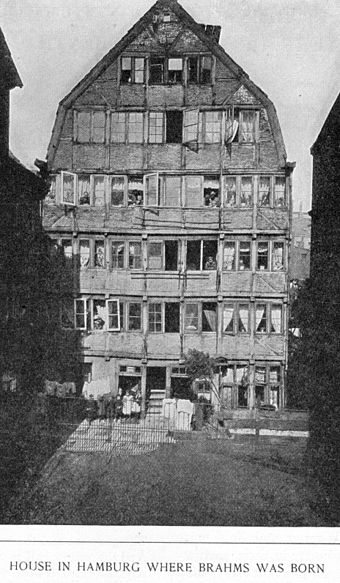

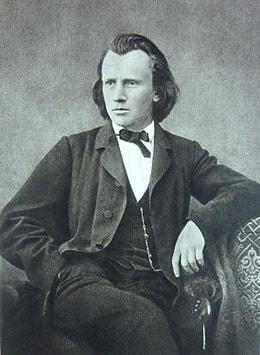

One could rightly say that the origin of the German Requiem lay in the early years of Brahms’s life. Born in 1833, he grew up in a very poor district of Hamburg with his musician father, his moderately educated mother, 17 years older than her husband, and his older sister and younger brother. An extraordinary bond existed between Johannes and his mother; her guidance anchored him through his early career until she became very frail in her old age.

In his teen years, Brahms’s study in Hamburg with Edward Marxsen in piano and composition nurtured his expressive artistry and a deep affinity to contrapuntal techniques. In spite of his formidable talent evident in his youthful concert tours and early compositions, Brahms’s career as a concert pianist and composer faced an uphill struggle for recognition in North Germany. Fortuitous associations, especially with the widely acclaimed violinist Joseph Joachim, opened a number of connections to him.

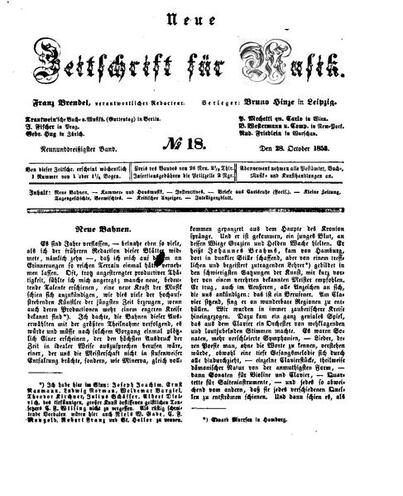

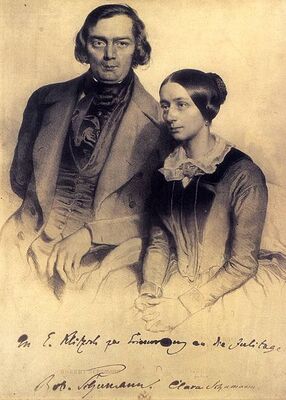

In 1853, at Joachim’s urging, Brahms entered the lives of Robert and Clara Schumann and acquired not only mentors roughly 20 years his senior but also an extended family. Settled with their six children in Düsseldorf, the two musicians took Brahms into their household and introduced him to an expanding circle of artists and musicians. It was Robert’s article, “Neue Bahnen” in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, predicting Brahms’s future as a leading exponent of absolute music, that brought the young composer to the attention of the European musical world.

Robert Schumann’s attempted suicide in 1854 deeply impacted his young protégé. Brahms began to attend to Clara more closely, especially after the birth of her seventh child and Robert’s hospitalization in an insane asylum in Endenich. He became the support of the despairing family, ultimately developing a deep love for Clara while still revering her husband. Robert died in 1856, and Brahms began a draft of a “Trauerkantata” that would never mature. However, uncompleted works begun in that tumultuous two-year period fed the germ of the German Requiem over the next ten years. Throughout that time, and indeed for the rest of his life, his and Clara’s love for each other, tempered away from its initial intensity, remained a foundation for continued correspondence.

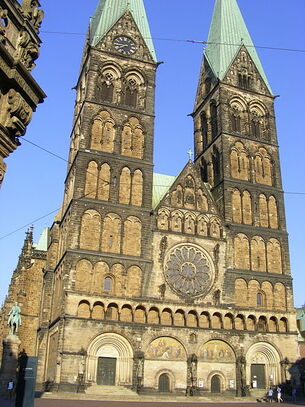

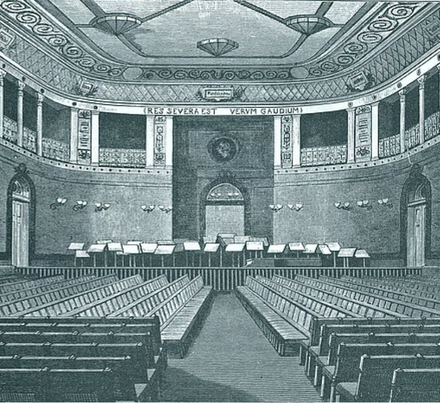

The final impetus to Brahms’s completion of an extended work of mourning was his mother’s death in early February 1865. By this time Brahms resided in Vienna and was unable to reach Hamburg in time to see her before she died. Deeply affected himself, and knowing that his sister especially would be deeply grieving, he devoted himself to composing a work that would offer comfort. He finished movements 1 and 4 soon after his mother’s death; by April he had already begun movements 2, 6, and 7, and told Clara that his new work was “a kind of German Requiem”. It is clear from Brahms’s rather long compositional process that these movements had been gestating for some time. By August of 1866 all movements except that with the soprano solo (the fifth) were finished. The first performance of movements 1 through 3 on December 1, 1867, in Vienna was badly marred by the unrelenting din—“a train going through a tunnel”, one critic wrote—created by the timpanist in the pedal fugue of the third movement. The following April 10, Good Friday, Brahms conducted the premiere of the six completed movements (without the soprano solo movement) in Bremen Cathedral, to great approval. The score of the completed seven-movement work went to the publisher, Rieter-Biedermann, in May 1868, and the entire German Requiem premiered successfully on February 18, 1869, at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, under Karl Reinecke’s direction.

In its final form, the 7-movement German Requiem calls for a full SATB chorus, soprano and baritone soloists, an orchestra consisting of piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (A, B-flat), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon ad. lib., 4 horns (F, low B-flat, low C, D, E-flat, E), 2 trumpets (B-flat, D, C) , 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, harp (doubled at least), strings, and organ ad. lib.

Musical Antecedents and the Text

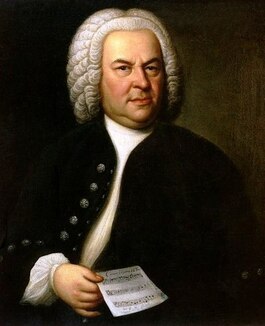

Greatly interested in German history and an avid collector and student of early music, Brahms was well aware of early precedents for a work of mourning in the music of the 17th-century North-German Protestant composer Heinrich Schütz and of Johann Sebastian Bach, in a German Requiem by Schubert, and even in the Requiem for Mignon by Robert Schumann.

Ferdinand Schubert's Requiem, Op. 9

Maastricht Kamerchor Conservatorium Musica Polyphonica, under the direction of Louis Devos

Bernadette Degelin, soprano | Lucienne Van Deyck, alto | Zeger Vandersteene, tenor | Kurt Widmer, bass

Maastricht Kamerchor Conservatorium Musica Polyphonica, under the direction of Louis Devos

Bernadette Degelin, soprano | Lucienne Van Deyck, alto | Zeger Vandersteene, tenor | Kurt Widmer, bass

Robert Schumann's Requiem für Mignon

Brigitte Lindner /Andrea Andonian/Mechthild Georg/Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau/Chor des Städt. Musikvereins zu Düsseldorf/Hartmut Schmidt/Düsseldorfer Symphoniker/Bernhard Klee

Several of the texts Schütz had selected for his Musickalische Exequien and psalm settings correspond with Brahms’s text. Early contrapuntal techniques such as canon and fugue fascinated Brahms and appear in the Requiem, as do old church modes. As a subscriber to the new complete edition of Bach’s works, published over 50 years from 1851, Brahms performed a number of that master’s works as a young musician and had more than a passing acquaintance with Bach’s music. Bach’s Cantata 106, “Gottes Zeit ist der allerbeste Zeit” (Actus Tragicus), and Cantatas 21 and 27 contain material which Brahms reused in the Requiem.

JS Bach's Cantata 106 | Netherlands Bach Society

JS Bach's Cantata 21 | Netherlands Bach Society

JS Bach's Cantata 27

But what does the title Ein deutsches Requiem—A German Requiem—mean? Dispel, if you will, the notion that the work is a vernacularized form of the Latin liturgical rite for the dead. It has nothing to do with rescuing a soul from Purgatory so that it might rest safely in Heaven. Brahms’s retention of the term “requiem” in the title does imply “rest”; but as one reads through the text of the work it becomes clear that what Brahms meant is “rest” or “respite” for the still-living, the mourners, rather than for the soul of the deceased.

More significant, though, is that the term “German”—indeed written in the German language—abuts the Latin term “requiem” in the title. This stunning incongruity represents a dichotomy of cultures in mid-nineteenth century Europe. At the time Brahms was composing the German Requiem, there was no country called Germany. In spite of the impulse to unify German-speaking states in the wake of Napoleon’s empire and the great thrust of German Romanticism particularly in the northern and western states, it wasn’t until 1871, the year after the victory of North German Confederation under Bismarck in the Franco-Prussian War, that the nation of Germany came into being. Most of Catholic Austria lay outside the new Germany, which was dominated by Protestant Prussia. Brahms, even though living and working in Vienna, both retained his identity as a North German and yet carefully avoided claiming that connection as the raison d’être for his Requiem. Concerned that his use of “German” in the work’s title might be construed as support for Bismarck, he deliberately negated any inclination to link him or the work to a nationalistic cause when he sarcastically pointed out the melodic resemblance between the first notes of the instrumental introduction to the German Requiem’s first movement to “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser”, Austria’s national anthem. He wrote to Karl Reinthaler, who prepared the Requiem for the Bremen Cathedral performance in 1868, that he would “very happily…omit the ‘German’ and simply put ‘Human’” as the descriptor in the work’s title. (A fuller examination of the issues of nationalism and religion may be found in Daniel Beller-McKenna’s article “How ‘deutsch’ a Requiem?” [Nineteenth-Century Life, 1998] and his book Brahms and the German Spirit [Harvard University Press, 2004].)

Brahms himself selected his texts from a work he knew very well: Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible. Luther’s Bible was an unequivocal link with the Lutheran tradition of North Germany, where Brahms was born and raised; and in this, too, the German Requiem had political and religious implications. This 16th-century landmark not only served to stabilize the written form of German language but also brought Holy Scripture to the common person in a universally understood vernacular during the growing Protestant Reformation. In correspondence with Reinthaler, Brahms revealed his clear understanding of theological implications of his text selections and his clear determination to avoid limiting the universal message of his Requiem with creedal texts such as John 3:16; but he defended his choice of texts that implied Christ’s second coming as “needed for the poetry”. Though a deeply spiritual person, Brahms was not a “practicing” Christian, and his text was not intended as an overt political or religious statement. It was reaching out to the ordinary person through Luther’s strikingly earthy and rich images.

Some Aspects of the Composition’s Structure

The German Requiem is an excellent example of Brahms’s life-long penchant for architectonic composition. Conceptual and formal relationships link the seven movements in various combinations. An arch form, the work pivots on the beautiful waltz of the fourth movement. The first and seventh movements begin with similar words and flow in a similarly consistent style, and the conclusion of the seventh movement recapitulates the music which ends the first, using similar texts. Movements two, three and six have clearly delineated sections marked by obvious changes in style. In these movements, the textual contents progress from a sorrowful focus on death to a joyful promise of relief from the burdens of life, victory over death, and the praise of God the creator. These three movements open with varieties of somber marches. Movements three and six feature a baritone soloist, who “teaches” the choir life lessons, and they conclude with massive fugues (in the sixth, a double fugue). Dances are evident in Movements 2, 4, and 6. The anomalous fifth movement, the last that Brahms composed, features a soprano soloist hovering over the choir.

Brahms gave coherence to the work through musical materials, some more obvious than others. Already mentioned are the “rhymed” endings of the first and last movements. More subtle is the pervasiveness of a core melodic motif throughout the work. Brahms acknowledged the Requiem’s foundation on a Bach chorale, which is believed to be “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten”, occurring in Cantata 21; Brahms had directed a performance of the cantata at the Detmold court in 1858. Various versions of the poetry which Bach had set to the chorale’s melody concern sorrow and death. In the German Requiem, Brahms took the first five notes of the old chorale as the opening theme of the orchestra. The theme begins with three scale-wise pitches rising from the tonic pitch, then returning by scale step to the tonic. This same theme occurs quite recognizably in other Brahms works, as early as 1858 in his Begräbnisgesang (Burial Song), Op. 13, and as late as 1896 in the second of the Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), Op. 121. In each case the theme is associated with texts about death, or burial, or the brevity of human life. This foundation motif occurs in the German Requiem many times: for instance, at the start of the choir’s minor-key melody at the beginning of the second movement, and as the basis of the vigorous victory dance in the sixth movement.

JS Bach's Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten

Vocal Concert Dresden

Vocal Concert Dresden

Brahms' Begräbnisgesang (Burial Song)

Sinfonieorchester (Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra)

Collegium Vocale Gent | Philippe Herreweghe, Dirigent

Sinfonieorchester (Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra)

Collegium Vocale Gent | Philippe Herreweghe, Dirigent

Brahms' Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), Op. 121

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Other musical elements unify the work as well. Rhythmically, for example, the heart-beat pulse in the low strings at the beginning of the first movement is related to the walking bass beneath the choir at the beginning of the third movement and again at the beginning of the sixth. Archaic modal harmonies, which delighted Brahms, appear briefly in the fifth movement but dominate the sixth, both at the beginning and in the magnificent double fugue. Other instances of melodic links usually pass below the listener’s sonar, such as the relation of the fugue subject of the third movement with the introduction (in inversion) and opening choral idea of the fourth.

Text Relationships between Movements

Numerous features of and details within the German Requiem give evidence of Brahms’s extraordinary insight into the texts he chose and into the process of grieving that they suggest. The orchestra accompaniment and the vocal parts interpret the texts with compassion, and rich symbolism is evident in the technical aspects of the music. In the following examination of the individual movements it will become evident that Brahms was building a cohesive picture of how one might understand not only the mourning of the bereaved but also how one might think of the condition of the soul of the departed. The picture he gives us slowly emerges through the course of the oratorio, achieving high points in the fifth and sixth movements.

The foundation of the work is the text. Translations will differ, of course, but one must remember that Brahms’s source was Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible, which differs from the nearly contemporaneous King James version. It is greatly beneficial to find, as nearly as possible, the meanings of the German text.

A careful reading of the text of the oratorio’s movements in order reveals connections that exist between them that differ from the musical connections indicated above. Here is a schema of those connections:

Movements 1 and 2 are linked by references to agriculture. The allusion to planting and reaping in Movement 1 suggests the transformation of grief to joy, while in Movement 2 the frank expression of the natural process of withering and dying of grass as an analogy to the inevitable end of human life reminds us that human beings are transient on this earth—and, as the following text of the movement says, only the Lord’s word remains eternal. What Movement 1 promises as the “reaping with joy” manifests as the march into Zion by “the redeemed of the Lord” in Movement 2.

Movement 3 follows Movement 2’s theme of human transience, but the textual perspective changes to one with more active involvement of the bereaved, who, being “instructed” by the baritone soloist, become participants in the journey through death to the next stage. They are, at the end of the movement, cast as “the souls of the righteous” who are beyond the trouble of the world. Movement 3 is linked by a subliminal chronology to their “song” in Movement 4, sung by the chorus and containing only text of praise. (There is, as well, a clear musical link to Movement 3.)

Movements 4 and 5, showing the terminus of the soul’s transition, are linked through their “portrayal” of the untroubled after-life message by the departed souls to the bereaved back in the present world. In this most personal of the movements of the oratorio, a soprano soloist projects the persona of Brahms’s own mother, recently deceased, while the chorus reinforces the message from the perspective of the bereaved.

Movements 6 and 7 suggest the longing of the living for the place shown in Movements 4 and 5. Movement 6 envisions the ancient search for the future place where death will be no more; it takes us through the transformation from life to that next state, where Death is destroyed and even mocked. After a great rejoicing at the end of Movement 6, Movement 7 once again reveals the beautiful, gracious, serene vision of what the departed soul will inherit: rest after a life of labor. It is that message which Brahms took to himself and evidently thought would bring comfort to his sister as well as to all mourners.

DISCUSSION OF THE MUSICAL SETTING OF THE TEXT

Translation: Judith Eckelmeyer © 2013

I prepared the following translation in 2013 originally for the performance of the German Requiem at Trinity Cathedral in March 2013. There have since been a few minor modifications. I hope this final version of the text will illuminate an understanding of what Brahms provided in his music, as his music illuminated his own understanding of the texts as he composed the work.

Translation: Judith Eckelmeyer © 2013

I prepared the following translation in 2013 originally for the performance of the German Requiem at Trinity Cathedral in March 2013. There have since been a few minor modifications. I hope this final version of the text will illuminate an understanding of what Brahms provided in his music, as his music illuminated his own understanding of the texts as he composed the work.

Movement 1

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen, denn sie sollen getröstet werden. Matthew 5:4.

Blessed are they who bear sorrow, for they shall be comforted.

Die mit tränen sähen, werden mit Freuden ernten. Sie gehen hin und weinen, und tragen edlen Samen, und kommen mit Freuden und bringen ihre Garben. Psalm 126:4-5.

They who sow with tears shall reap with joy.

They go forth and weep, and bear precious seed, and come with joy, and bring their sheaves.

***

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen, denn sie sollen getröstet werden. Matthew 5:4.

Blessed are they who bear sorrow, for they shall be comforted.

Die mit tränen sähen, werden mit Freuden ernten. Sie gehen hin und weinen, und tragen edlen Samen, und kommen mit Freuden und bringen ihre Garben. Psalm 126:4-5.

They who sow with tears shall reap with joy.

They go forth and weep, and bear precious seed, and come with joy, and bring their sheaves.

***

There are two themes represented in the texts from two sources. The first, from the Gospel of Matthew, sets the topic of the entire oratorio: comforting those who grieve. The second, from a Psalm, introduces an agricultural theme that suggests that, in an organic transformation, grief, allowed to mature, will produce its fruit, and this fruit will provide sustenance and even joy.

Brahms created a subliminally darkened sonic environment for his opening thoughts by eliminating violins from the entire movement; the violas, divided into two sections, and cellos, divided into three sections, and the basses form the string ensemble.

The work opens with an orchestral introduction in the low range, in F major, with a pulsing pedal tone, reinforced by low horn octaves. Above, two other key elements slowly unfold: the leading tone, resolving down to the sixth (E-flat to D), and the three-note figure rising from the tonic and falling back again, mentioned earlier, that is thought to reflect Brahms’s remembrance of a Bach chorale. After 14 measures of this dark, lush preparation, the choir enters unaccompanied, in a stunningly simple statement: “Blessed are they....” Here is the essence of Brahms’s message to the bereaved. There is a pause in the choir as the strings fill in briefly. Then the choir resumes with its full statement, again unaccompanied. The effect is, remarkably, that of a human touch of consolation, devoid of anything save the voice with pitch and the gentle rhythm of words of comfort. Only after this opening statement do other instruments—flutes, oboes, bassoon, trombones and harps—join in to brighten and lift the repetition of the first thought.

After a brief woodwind closure to the promise of comfort, a new idea appears in a widely different key, D-flat major, and now including the texture and brightness of harp arpeggios. The text is widely different, too. It describes the sower going out with tears (portrayed by gently descending sequences of sighs) to broadcast precious seed; but then, after the seed has lain in the ground, germinated and grown to maturity, he returns joyfully with his harvest of the sheaves (beginning with a more lively, upward swinging melody). This image gives a tiny hint of the grief-to-joy progression that will occur in subsequent movements, and begins Brahms’s gradual presentation of his vision of the progress of the soul of the departed.

Brahms rounds out the movement by returning to F major and revisiting the first idea of comforting the bereaved. The conclusion is important, as it will return almost verbatim to end the entire oratorio.

1st Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Selig sind

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Selig sind

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Movement 2

Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras und alle Herrlichkeit des Menschen wie des Grases Blumen. Das Gras ist verdorret und die Blume abgefallen. I Peter 1:24.

For all flesh is like grass, and all splendor of humankind like the flowers of grass.

The grass has withered and the flower fallen off.

So seid nun geduldig, lieben Brüder, bis auf die Zukunft des Herrn. Siehe ein Ackermann wartet auf die köstliche Frucht der Erde und ist geduldig darüber, bis er empfahe den Morgenregen und den Abendregen. So seid geduldig. James 5:7.

So now be patient, dear brothers, till the coming of the Lord. Look, a farmer waits for the precious fruit of the earth and is patient about it, until he receive the morning rain and the evening rain. So be patient.

Aber des Herrn Wort bleibet in Ewigkeit. I Peter 1:25.

But the word of the Lord remains forever.

Die Erlöseten des Herrn werden wieder kommen, und gen Zion kommen mit Jauchzen; ewige Freude wird über ihrem Haupte sein; Freude und Wonne werden sie ergreifen, und Schmerz und Seufzen wird weg müssen. Isaiah 35:10.

The redeemed of the Lord shall return, and come with shouts of joy to Zion; eternal joy shall be over their heads;

joy and delight shall move them, and torment and sighing shall have to be gone.

***

Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Gras und alle Herrlichkeit des Menschen wie des Grases Blumen. Das Gras ist verdorret und die Blume abgefallen. I Peter 1:24.

For all flesh is like grass, and all splendor of humankind like the flowers of grass.

The grass has withered and the flower fallen off.

So seid nun geduldig, lieben Brüder, bis auf die Zukunft des Herrn. Siehe ein Ackermann wartet auf die köstliche Frucht der Erde und ist geduldig darüber, bis er empfahe den Morgenregen und den Abendregen. So seid geduldig. James 5:7.

So now be patient, dear brothers, till the coming of the Lord. Look, a farmer waits for the precious fruit of the earth and is patient about it, until he receive the morning rain and the evening rain. So be patient.

Aber des Herrn Wort bleibet in Ewigkeit. I Peter 1:25.

But the word of the Lord remains forever.

Die Erlöseten des Herrn werden wieder kommen, und gen Zion kommen mit Jauchzen; ewige Freude wird über ihrem Haupte sein; Freude und Wonne werden sie ergreifen, und Schmerz und Seufzen wird weg müssen. Isaiah 35:10.

The redeemed of the Lord shall return, and come with shouts of joy to Zion; eternal joy shall be over their heads;

joy and delight shall move them, and torment and sighing shall have to be gone.

***

This is the first movement with major sections showing a progression from grief to joy, realized in three distinct sections.

Within the first section the agricultural theme, touched on in the first movement, is expanded. At first, human life is likened to common grass, and human death to the withering and falling off of the grass’s flower and seed. The setting of this first text is memorable. In B-flat minor, it is marked “slowly, marchlike”, and so, although in triple meter, Brahms presents an unusual funeral procession. In fact, this “procession” begins very softly, with only the lower three choral voices, and gradually grows to a massive fortissimo, as if it is standing directly before the listener, confronting us with the reality of death.

Recall that the first movement was darkened by the omission of violins. A kind of dimness continues in this opening section of Movement 2. It includes violins, but their strings are muted, creating haziness or a sense of distance. The orchestra’s introduction conveys three ideas. In the bass is an upward swaying motif, dominant to tonic or subdominant to tonic, in the rhythm of a Ländler, a commoner’s slow dance. In the upper strings and woodwinds is a descending motif with a dotted rhythm on the second beat, typical of an aristocratic sarabande from the Baroque. And third, in the timpani is a persistent beat with a triplet on the third beat, essentially a dirge drumbeat; in Brahms’ time the triplet was a recognized symbol referring to death and “fate” (think Beethoven’s Symphony 5). These three musical concepts suggest that death links the whole range of humanity in the common experience of death. In the midst of this orchestral sound, the choir intones in unison the Requiem’s principal funeral concept that all of us will die someday; their melody is derived from the first movement’s motive associated with the Bach chorale.

Some respite is provided when a lighter intermediate section considers the need for patience, like that of the farmer awaiting revivifying rain that will bring the harvest. In G-flat major, this section opens with the unaccompanied choir, in a somewhat faster tempo and with a gentle waltz rhythm, gracefully urging patience for the coming of the Lord. Instruments answering the choir are the woodwinds, again lightening the sonority. At the reference to rain, the harps enter with points of arpeggiated sound suggesting raindrops.

Then there is a literal return of the funeral march, testing the patience of those who mourn.

A sudden, very bright announcement in B-flat major wrenches us away from the minor-key funeral march. The choir, with flutes, oboes, trombones and tuba, pronounces “But the Lord’s word...” as a fanfare with rhythmic energy. The strings, now without mutes, take up an excited arpeggio pattern to support the choir as it states the rest of its announcement: “…remains forever.” On the word “forever”, flutes, oboes and trumpets begin a dotted rhythm that gathers steam and feeds the third section of the movement.

The third section is yet another march, this time in B-flat major and Common Time. Here is the message about the departed: they are the redeemed, coming with shouts of joy into Zion, where pain and sighing are no more. The opening triadic motif, taken up by the orchestra, follows and surrounds the choir throughout the remainder of the march, reminding always of the promise to the redeemed. “Pain” and “sighing” interrupt with a darkening minor key and a traditional sigh motif; they are thrust away with sharp staccato chords. Emerging from this dark episode, the choir mounts a great Jauchzer—a shout of joy—on the word Jauchzen as the redeemed “come…to Zion”. Brahms graphically denotes “eternal” joy in a gentle coda in which a grand major scale rises from the lowest strings through the highest and back down again, while the “redeemed” motif hovers in the brasses around the calm, hushed choir.

Within the first section the agricultural theme, touched on in the first movement, is expanded. At first, human life is likened to common grass, and human death to the withering and falling off of the grass’s flower and seed. The setting of this first text is memorable. In B-flat minor, it is marked “slowly, marchlike”, and so, although in triple meter, Brahms presents an unusual funeral procession. In fact, this “procession” begins very softly, with only the lower three choral voices, and gradually grows to a massive fortissimo, as if it is standing directly before the listener, confronting us with the reality of death.

Recall that the first movement was darkened by the omission of violins. A kind of dimness continues in this opening section of Movement 2. It includes violins, but their strings are muted, creating haziness or a sense of distance. The orchestra’s introduction conveys three ideas. In the bass is an upward swaying motif, dominant to tonic or subdominant to tonic, in the rhythm of a Ländler, a commoner’s slow dance. In the upper strings and woodwinds is a descending motif with a dotted rhythm on the second beat, typical of an aristocratic sarabande from the Baroque. And third, in the timpani is a persistent beat with a triplet on the third beat, essentially a dirge drumbeat; in Brahms’ time the triplet was a recognized symbol referring to death and “fate” (think Beethoven’s Symphony 5). These three musical concepts suggest that death links the whole range of humanity in the common experience of death. In the midst of this orchestral sound, the choir intones in unison the Requiem’s principal funeral concept that all of us will die someday; their melody is derived from the first movement’s motive associated with the Bach chorale.

Some respite is provided when a lighter intermediate section considers the need for patience, like that of the farmer awaiting revivifying rain that will bring the harvest. In G-flat major, this section opens with the unaccompanied choir, in a somewhat faster tempo and with a gentle waltz rhythm, gracefully urging patience for the coming of the Lord. Instruments answering the choir are the woodwinds, again lightening the sonority. At the reference to rain, the harps enter with points of arpeggiated sound suggesting raindrops.

Then there is a literal return of the funeral march, testing the patience of those who mourn.

A sudden, very bright announcement in B-flat major wrenches us away from the minor-key funeral march. The choir, with flutes, oboes, trombones and tuba, pronounces “But the Lord’s word...” as a fanfare with rhythmic energy. The strings, now without mutes, take up an excited arpeggio pattern to support the choir as it states the rest of its announcement: “…remains forever.” On the word “forever”, flutes, oboes and trumpets begin a dotted rhythm that gathers steam and feeds the third section of the movement.

The third section is yet another march, this time in B-flat major and Common Time. Here is the message about the departed: they are the redeemed, coming with shouts of joy into Zion, where pain and sighing are no more. The opening triadic motif, taken up by the orchestra, follows and surrounds the choir throughout the remainder of the march, reminding always of the promise to the redeemed. “Pain” and “sighing” interrupt with a darkening minor key and a traditional sigh motif; they are thrust away with sharp staccato chords. Emerging from this dark episode, the choir mounts a great Jauchzer—a shout of joy—on the word Jauchzen as the redeemed “come…to Zion”. Brahms graphically denotes “eternal” joy in a gentle coda in which a grand major scale rises from the lowest strings through the highest and back down again, while the “redeemed” motif hovers in the brasses around the calm, hushed choir.

2nd Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Denn alles Fleisch

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Denn alles Fleisch

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Movement 3

Herr, lehre doch mich, dass ein Ende mit mir haben muss, und mein Leben ein Ziel hat, und ich davon muss. Siehe, meine Tage sind einer Handbreit vor dir, und mein Leben ist wie nichts vor dir. Ach, wie gar nichts sind alle Menschen die doch so sicher leben. Sie gehen daher wie ein Schemen, und machen ihnen viel vergebliche Unruhe; sie sammeln und wissen nicht wer es kriegen wird. Nun Herr, wes soll ich mich trösten? Ich hoffe auf dich. Psalm 39:4-8.

Lord, do teach me that there has to be an end to me, and my life has a limit, and I must away. See, my days are a hand’s breadth before you, and my life is as nothing before you. Ah, all humans are as nothing at all, who nevertheless live so confidently. They go around like a specter, and make themselves uneasy for no reason; they accumulate and do not know who shall inherit it. Now, Lord, in what shall I take comfort? My hope is in you.

Der Gerechten Seelen sind in Gottes Hand und keine Qual rühret sie an. Wisdom 3:1.

The souls of the righteous are in God’s hand, and no anguish touches them.

***

Herr, lehre doch mich, dass ein Ende mit mir haben muss, und mein Leben ein Ziel hat, und ich davon muss. Siehe, meine Tage sind einer Handbreit vor dir, und mein Leben ist wie nichts vor dir. Ach, wie gar nichts sind alle Menschen die doch so sicher leben. Sie gehen daher wie ein Schemen, und machen ihnen viel vergebliche Unruhe; sie sammeln und wissen nicht wer es kriegen wird. Nun Herr, wes soll ich mich trösten? Ich hoffe auf dich. Psalm 39:4-8.

Lord, do teach me that there has to be an end to me, and my life has a limit, and I must away. See, my days are a hand’s breadth before you, and my life is as nothing before you. Ah, all humans are as nothing at all, who nevertheless live so confidently. They go around like a specter, and make themselves uneasy for no reason; they accumulate and do not know who shall inherit it. Now, Lord, in what shall I take comfort? My hope is in you.

Der Gerechten Seelen sind in Gottes Hand und keine Qual rühret sie an. Wisdom 3:1.

The souls of the righteous are in God’s hand, and no anguish touches them.

***

The text of this movement progresses from a lesson on the limit of life, to questioning where to find comfort, to the secure knowledge that the souls of the righteous are safe with God. Two large sections, in D minor and D major, are followed by an extended passage of troubled, unresolved tension answered by a nine-measure affirmation of the dominant of D major leading to a long fugue in D major.

For the first time, a soloist enters the musical sphere. The baritone soloist “teaches” the choir that all of us are “terminal” and insignificant compared to God; the choir learns by repeating the lesson, phrase by phrase. The first two sentences are structured in three segments, the first sentence returning to close this first section with the words “I must away”. As if struck by the finality of this message, the orchestra reacts with a loud outburst, violins struggling in a high range with the melody built on the funeral motif from the first two movements; the lower strings, horns and timpani underlay a triplet rhythm reminiscent of the second-movement’s funeral march.

Once the orchestra calms down again, the baritone resumes in D major with a meditation on the vanity of human life. Dutifully, the choir repeats the lesson but is clearly disquieted by it. Once finished with their statement of the lesson, they move into a chromatic fugato section, asking where to find comfort. Their cadence on a diminished chord is mercifully resolved as they realize their hope is in God. The beautiful transition to the next section incorporates the previously ominous triplets as well as the elements of the funeral motif well absorbed into gracious melody, suggesting the acceptance of human mortality.

From the acceptance of mortality comes the confidence of the safety of the soul in God’s hands. Brahms sets this as a pedal fugue, a contrapuntal procedure unfolding over a single tone symbolizing arrival at a home and an unshakeable faith. The unremitting low D in the string basses, brasses, and contrabassoon is reinforced by the timpani: there is no doubt where the key center is here! The fugue subject is a long arching melody covering an octave and a fourth, again incorporating elements of the central funeral motif. A master of the baroque procedure of fugue, Brahms uses the old techniques to their fullest. A marvelous stretto drives the movement to its glorious conclusion.

Once the orchestra calms down again, the baritone resumes in D major with a meditation on the vanity of human life. Dutifully, the choir repeats the lesson but is clearly disquieted by it. Once finished with their statement of the lesson, they move into a chromatic fugato section, asking where to find comfort. Their cadence on a diminished chord is mercifully resolved as they realize their hope is in God. The beautiful transition to the next section incorporates the previously ominous triplets as well as the elements of the funeral motif well absorbed into gracious melody, suggesting the acceptance of human mortality.

From the acceptance of mortality comes the confidence of the safety of the soul in God’s hands. Brahms sets this as a pedal fugue, a contrapuntal procedure unfolding over a single tone symbolizing arrival at a home and an unshakeable faith. The unremitting low D in the string basses, brasses, and contrabassoon is reinforced by the timpani: there is no doubt where the key center is here! The fugue subject is a long arching melody covering an octave and a fourth, again incorporating elements of the central funeral motif. A master of the baroque procedure of fugue, Brahms uses the old techniques to their fullest. A marvelous stretto drives the movement to its glorious conclusion.

3rd Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Herr, lehre doch mich

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Franz Crass, baritono

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Herr, lehre doch mich

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Franz Crass, baritono

Movement 4

Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen, Herr Zebaoth, Meine Seele verlanget und sehnet sich nach den Vorhöffen des Herrn; mein Leib und Seele freuen sich in dem lebendigen Gott. Wohl denen, die in deinem Hause wohnen, die loben dich immerdar. Psalm 84:1-2, 4.

How lovely are your dwellings, Lord of hosts. My soul craves and yearns for the forecourts of the Lord;

my body and soul rejoice in the living God. Happy they, who live in your house, who praise you forever.

***

Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen, Herr Zebaoth, Meine Seele verlanget und sehnet sich nach den Vorhöffen des Herrn; mein Leib und Seele freuen sich in dem lebendigen Gott. Wohl denen, die in deinem Hause wohnen, die loben dich immerdar. Psalm 84:1-2, 4.

How lovely are your dwellings, Lord of hosts. My soul craves and yearns for the forecourts of the Lord;

my body and soul rejoice in the living God. Happy they, who live in your house, who praise you forever.

***

As the structural center of the German Requiem, this movement, in E-flat major, flows naturally from the previous fugue. For one thing, the third-movement’s fugue’s subject appears in inverted form in flutes and clarinet to introduce this fourth movement; and, it is transformed in its original form into the melody of a beautiful waltz, suggesting the beauty and graciousness of God’s dwelling place, where the souls of the righteous reside. No trouble lurks here; the text is only praise—the praise of those who, as Movement 3 tells us, are now in God’s hands.

4th Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Movement 5

Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit; aber ich will euch wieder sehen und euer Herz soll sich freuen und eure Freude soll niemand von euch nehmen.

John 16:22.

Now you have sorrow; but I will see you again, and your heart shall rejoice, and no one shall take your joy from you.

Ich will euch trösten, wie einen seine Mutter tröstet. Isaiah 66:13.

I will comfort you like one’s mother comforts him.

Sehet mich an: ich habe eine kleine Zeit Mühe und Arbeit gehabt, und habe grossen Trost funden. Ecclesiasticus 51:35.

Look at me: for a little while I had trouble and toil, and have found great comfort.

***

Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit; aber ich will euch wieder sehen und euer Herz soll sich freuen und eure Freude soll niemand von euch nehmen.

John 16:22.

Now you have sorrow; but I will see you again, and your heart shall rejoice, and no one shall take your joy from you.

Ich will euch trösten, wie einen seine Mutter tröstet. Isaiah 66:13.

I will comfort you like one’s mother comforts him.

Sehet mich an: ich habe eine kleine Zeit Mühe und Arbeit gehabt, und habe grossen Trost funden. Ecclesiasticus 51:35.

Look at me: for a little while I had trouble and toil, and have found great comfort.

***

The emotional center of the work, and perhaps for Brahms, the core apocalypse (or revelation of what is in store for us at the end) is this soprano solo on the texts of John and Ecclesiasticus, riding above the choir’s text from Isaiah and a gentle accompaniment. Brahms invokes the “voice” of his own mother saying she has found great comfort. At the very end, her words no longer say “ich will euch wieder sehen” (“I’ll see you again”), but instead give the informal truncated form of “goodbye”—“wiedersehen”—as the accompaniment fades away.

5th Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Wilma Lipp, Soprano

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Wilma Lipp, Soprano

Movement 6

Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt, sondern die zukünftige suchen wir. Hebrews 13:14.

For here we have no enduring place, but rather we seek that of the future.

Siehe, ich sage euch ein Geheimnis. Wir werden nicht alle entschlafen, aber alle verwandelt werden; und dasselbige plötzlich in einem Augenblick zu der Zeit der letzten Posaune. Denn es wird die Posaune schallen und die Toten werden auferstehen unverweslich, und wir werden verwandelt werden. I Corinthians 15:51-52.

See, I tell you a mystery. We shall not all die but shall all be transformed, and that suddenly in an instant, at the time of the last trumpet. For the trumpet shall sound and the dead shall rise imperishable, and we shall be transformed.

Dann wird erfüllet werden das Wort, das geschrieben steht: Der Tod ist verschlungen in den Sieg. Tod, wo ist dein Stachel! Hölle, wo ist dein Sieg! I Corinthinans 15:54-55.

Then the word that stands written shall be fulfilled: Death is consumed in victory.

Death, where is your thorn! Hell, where is your victory!

Herr, du bist würdig zu nehmen Preis und Ehre und Kraft, denn du hast alle Dinge erschaffen, und durch deinen Willen haben sie das Wesen und sind geschaffen. Revelation 4:11.

Lord, you are worthy to receive praise and honor and strength, for you have created all things,

and through your will they have being and are created.

***

Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt, sondern die zukünftige suchen wir. Hebrews 13:14.

For here we have no enduring place, but rather we seek that of the future.

Siehe, ich sage euch ein Geheimnis. Wir werden nicht alle entschlafen, aber alle verwandelt werden; und dasselbige plötzlich in einem Augenblick zu der Zeit der letzten Posaune. Denn es wird die Posaune schallen und die Toten werden auferstehen unverweslich, und wir werden verwandelt werden. I Corinthians 15:51-52.

See, I tell you a mystery. We shall not all die but shall all be transformed, and that suddenly in an instant, at the time of the last trumpet. For the trumpet shall sound and the dead shall rise imperishable, and we shall be transformed.

Dann wird erfüllet werden das Wort, das geschrieben steht: Der Tod ist verschlungen in den Sieg. Tod, wo ist dein Stachel! Hölle, wo ist dein Sieg! I Corinthinans 15:54-55.

Then the word that stands written shall be fulfilled: Death is consumed in victory.

Death, where is your thorn! Hell, where is your victory!

Herr, du bist würdig zu nehmen Preis und Ehre und Kraft, denn du hast alle Dinge erschaffen, und durch deinen Willen haben sie das Wesen und sind geschaffen. Revelation 4:11.

Lord, you are worthy to receive praise and honor and strength, for you have created all things,

and through your will they have being and are created.

***

This movement is another instance of sectional progression, in this case from the sense of unrest in the present life, through a moment of understanding and a vision of victory over death—the death of death—and a grand, triumphant song of praise.

Brahms begins the movement in an ancient mode with its archaic harmonies, which suggest an ancient search of those seeking a place of rest. No tonal center can be located; there is no place to sit down, figuratively. (This would be an antithesis of the concept of the pedal tone in the fugue ending Movement 3.) As if trying to get to that place of comfort, the choir at first wanders fruitlessly, as the “walking” bass suggests. Brahms is describing the age-old and timeless search for the realm that is to come. The baritone “teacher” presents another apocalypse (in F-sharp minor): that there will be no death, no falling asleep, but rather a transformation, signaled by a trumpet call at the last moment, and again, the chorus dutifully repeats his statement. Rising melodic material accompanying the revelation does, in fact, become energized to represent the awakening and rising up of the dead in their new existence.

The transformation in the subsequent vivid triple-meter dance, in C minor, occurs in the melody, which is a version of the funeral theme first heard at the beginning of Movement 1. This now is set as an earthy Ländler—a folk dance, not an aristocratic waltz. The contrast to the second movement use of the theme as a funeral dirge is striking. Whereas there it represented the unity of human beings in the experience of death, now it suggests the prospect of an ongoing existence of all souls, overcoming or “swallowing up” death at the last. Brahms gives us not a battle but rather a rugged victory dance to celebrate the overcoming of death. Cementing the image is the final cadence of this section on a prolonged C-major chord.

Emerging from that chord is the elegant first subject of what will unfold as a great C-major double fugue; each of the two phrases of the text has its own melody. The first of these begins with an interesting rhythm, long-short-short, stated twice; those who know Schubert’s music will recognize its association with the topic of death in that composer’s works. Perhaps Brahms, who knew Schubert’s works, saw yet another way to symbolize overcoming death through the very act of praising God. The second subject of this great fugue (denn du hast alle Dinge erschaffen…) is gentle and wide-ranging, occupying not only the tenors but then extending upwards to the altos and finally the sopranos for its fullest extension—truly “all things” are encompassed in it! Eventually, a great rising figure in the orchestra appears. It is formed by an ascending second (two scale steps) followed by a rising third, then continuing this pattern through seven measures, beginning in the contrabassoon’s low C, and climbing up through the entire choir and out through the top of the highest instruments. Whether Brahms thought this gesture suggested a resurrection of sorts or praise rising heavenward, it leaves an indelible impression of ascent and even increasing weightlessness at that moment. Archaic modal harmonies reappear, again suggesting the timelessness of the song of praise. After a modal approach, the great final C-major cadence affirms God’s power.

Brahms begins the movement in an ancient mode with its archaic harmonies, which suggest an ancient search of those seeking a place of rest. No tonal center can be located; there is no place to sit down, figuratively. (This would be an antithesis of the concept of the pedal tone in the fugue ending Movement 3.) As if trying to get to that place of comfort, the choir at first wanders fruitlessly, as the “walking” bass suggests. Brahms is describing the age-old and timeless search for the realm that is to come. The baritone “teacher” presents another apocalypse (in F-sharp minor): that there will be no death, no falling asleep, but rather a transformation, signaled by a trumpet call at the last moment, and again, the chorus dutifully repeats his statement. Rising melodic material accompanying the revelation does, in fact, become energized to represent the awakening and rising up of the dead in their new existence.

The transformation in the subsequent vivid triple-meter dance, in C minor, occurs in the melody, which is a version of the funeral theme first heard at the beginning of Movement 1. This now is set as an earthy Ländler—a folk dance, not an aristocratic waltz. The contrast to the second movement use of the theme as a funeral dirge is striking. Whereas there it represented the unity of human beings in the experience of death, now it suggests the prospect of an ongoing existence of all souls, overcoming or “swallowing up” death at the last. Brahms gives us not a battle but rather a rugged victory dance to celebrate the overcoming of death. Cementing the image is the final cadence of this section on a prolonged C-major chord.

Emerging from that chord is the elegant first subject of what will unfold as a great C-major double fugue; each of the two phrases of the text has its own melody. The first of these begins with an interesting rhythm, long-short-short, stated twice; those who know Schubert’s music will recognize its association with the topic of death in that composer’s works. Perhaps Brahms, who knew Schubert’s works, saw yet another way to symbolize overcoming death through the very act of praising God. The second subject of this great fugue (denn du hast alle Dinge erschaffen…) is gentle and wide-ranging, occupying not only the tenors but then extending upwards to the altos and finally the sopranos for its fullest extension—truly “all things” are encompassed in it! Eventually, a great rising figure in the orchestra appears. It is formed by an ascending second (two scale steps) followed by a rising third, then continuing this pattern through seven measures, beginning in the contrabassoon’s low C, and climbing up through the entire choir and out through the top of the highest instruments. Whether Brahms thought this gesture suggested a resurrection of sorts or praise rising heavenward, it leaves an indelible impression of ascent and even increasing weightlessness at that moment. Archaic modal harmonies reappear, again suggesting the timelessness of the song of praise. After a modal approach, the great final C-major cadence affirms God’s power.

6th Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Franz Crass, Baritono

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Franz Crass, Baritono

Movement 7

Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herren sterben, von nun an. Ja, der Geist spricht, dass sie ruhen von ihrer Arbeit, den ihre Werke folgen ihnen nach. Revelation 14:13

Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.

Indeed, the spirit says, that they rest from their labor, and their works live after them.

***

Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herren sterben, von nun an. Ja, der Geist spricht, dass sie ruhen von ihrer Arbeit, den ihre Werke folgen ihnen nach. Revelation 14:13

Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.

Indeed, the spirit says, that they rest from their labor, and their works live after them.

***

In this final movement, Brahms returns to F-major, the key of the first movement. In spite of the low-range opening in the strings, much like the opening of Movement 1, the atmosphere is much different. Notes occur on every half beat in an upward major scale, giving lightness, almost a suggestion of the beating of wings rising into the air. Out of this rising introduction, the choir’s sopranos hover and, in a long, gracious melody in an inverted arch, pronounce blessedness for the dead who die in the Lord. The tenors restate the melody, then other voices join. Using an old tradition for symbolizing the world of the supernatural, Brahms introduces the pronouncement of the Spirit with a trombone accompaniment, with the lower choral voices in unison. Now in A-major, the choir amplifies the concept of rest from labor and the remembrance of the work of the departed, changing to the key of E major.

The Spirit speaks again, beginning a passage of key transitions out of which the final section of the movement can return to F major. Tenors, now in F, give a recapitulation of the opening melody and the first material of the movement, but in a flurry of triplets the music sinks to E-flat. As if out of a dark memory, a principal melody from Movement I appears in the altos, continued in the tenors, on the words “Selig sind die Toten…”, “Blessed are the dead…” rather than “Blessed are they who mourn”. Brahms takes this idea through several statements and several key centers. On the way, he builds in a remembrance of the triplet rhythms that have suggested the funeral cadence in Movement II, the frustration of seeking a source of trust in Movement 3, and the great dance of victory in Movement 6. Finally settling on a cadence in F, he re-employs the music that ended Movement 1 using the text of Movement 7, shifting the focus from “those who bear grief” to “those who die in the Lord”.

The Spirit speaks again, beginning a passage of key transitions out of which the final section of the movement can return to F major. Tenors, now in F, give a recapitulation of the opening melody and the first material of the movement, but in a flurry of triplets the music sinks to E-flat. As if out of a dark memory, a principal melody from Movement I appears in the altos, continued in the tenors, on the words “Selig sind die Toten…”, “Blessed are the dead…” rather than “Blessed are they who mourn”. Brahms takes this idea through several statements and several key centers. On the way, he builds in a remembrance of the triplet rhythms that have suggested the funeral cadence in Movement II, the frustration of seeking a source of trust in Movement 3, and the great dance of victory in Movement 6. Finally settling on a cadence in F, he re-employs the music that ended Movement 1 using the text of Movement 7, shifting the focus from “those who bear grief” to “those who die in the Lord”.

7th Movement

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Selig sind die Toten

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, Selig sind die Toten

Weiner Symphoniker, W. Sawallisch

Singverein der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2013

Complete Performance

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem op. 45

Christiane Karg, Sopran | Michael Nagy, Bariton

MDR-Rundfunkchor | Nicolas Fink, Choreinstudierung

Sinfonieorchester – Frankfurt Radio Symphony | David Zinman, Dirigent

Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem op. 45

Christiane Karg, Sopran | Michael Nagy, Bariton

MDR-Rundfunkchor | Nicolas Fink, Choreinstudierung

Sinfonieorchester – Frankfurt Radio Symphony | David Zinman, Dirigent

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.