- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

Schubert Symphonies 8 and 9

by Judith Eckelmeyer

(GRACE WOODS MUSIC SESSION AUGUST 28, 2023)

I think sometimes we lose track of relationships between composers and their near contemporaries, immediate predecessors or successors. For instance, Mozart had died in Vienna well before Franz Schubert was born there (January 1797). But Joseph Haydn was still very much alive and composing in England and Vienna while Schubert was growing up in the imperial capital.

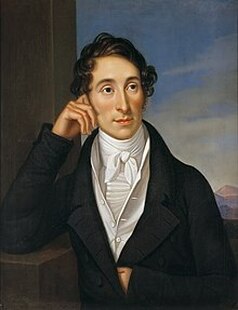

Mozart’s associates Salieri and Eybler were Schubert’s examiners at the Imperial and Royal City College where Schubert excelled as a music student; Salieri became Schubert’s music tutor. The composer of early Romantic operas,

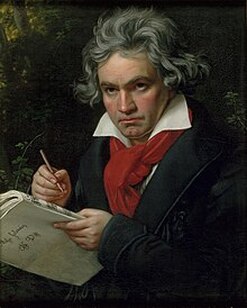

Carl Maria Von Weber (1786-1826), was active throughout Germany and Austria. And of course, in Schubert’s lifetime Beethoven lived, composed, and died in Vienna. Schubert played the music of Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven, rounding out the connection between the composers of the (first) Viennese School.

We have explored (LINK) three of Schubert’s early Lieder, one of which, Der Erlkönig, brought him early recognition and success throughout Europe. Along with dramatic works, choral works, chamber music, short orchestral works such as overtures, and of course Lieder, Schubert began composing symphonies.

He completed his first numbered symphony, D82 in D major, in 1813, at age 16, and his second and third (D125 in B-flat major and D200 in D major, respectively) the following year.

Schubert's Symphony No. 1 in D-major, D. 82 (1813)

Failoni Orchestra | Michael Halász, conductor

Failoni Orchestra | Michael Halász, conductor

Schubert's Symphony No. 2 in B-flat major, D. 125

Frankfurt Radio Symphony | Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Director

Frankfurt Radio Symphony | Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Director

Schubert's Symphony No. 3 in D major, D. 200

Frankfurt Radio Symphony | Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Director

Frankfurt Radio Symphony | Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Director

By the last decade of his life, Schubert’s style had matured, no longer reflecting the late classical style of Mozart and Haydn. Certainly Beethoven’s music was an influence in this maturation. But we shouldn’t short-change Schubert. His own special imagination, ability to conjure up beautiful melodies, unique ways of moving from one key to another, and evocation of mystery and even terror are quite unique to him—and evident in the 8th and 9th symphonies.

Symphony 8, D759 in B-minor, is “unfinished” because it has only two movements completed by Schubert; it was composed in the fateful year of 1822. It is notable in several ways besides its truncated body. First, its two movements, Allegro and Andante con moto, are both in triple meter, which was unusual for that time. Second, Schubert included three trombones. These instruments traditionally had portended supernatural events in operas (remember Don Giovanni?) and in Mass settings to reinforce vocal lines or add dramatic color to a scene, but not in purely instrumental symphonies. By the time Schubert composed this work, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, using 2 trombones, had been completed, performed and celebrated in writings by a music critic, none other than E.T.A. Hoffmann. This set up a precedent for Schubert. Besides the orchestral richness, the “Unfinished” also had memorable melodies which Schubert worked in many ways, through numerous key changes, and undergirded with instances of surprising drama.

Schubert's Symphony No. 8 in B-minor "Unfinished"

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, director

(00:00) I. Allegro moderato

(15:00) II. Andante con moto

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, director

(00:00) I. Allegro moderato

(15:00) II. Andante con moto

Schubert began writing the “Great” C-major symphony in 1824, while vacationing in Gastein, Upper Austria, calling it a symphony “for large orchestra”. He completed the work in 1826. Indeed, it was a work for an extensive ensemble, requiring not only the usual strings, winds and tympani, but also expanded brass: 2 horns, 2 trumpets and 3 trombones. Schubert used the trombones as essential ingredients to the sonority of the work, not momentary colorism. The symphony’s performance length was also “grand”—about an hour with all repeats Schubert indicated. It was originally called the 7th symphony, but later renumbered as the 8th in Otto Erich Deutsch’s catalog; American scholars consider it the 9th. Very confusing. As with so many of Schubert’s works, it was not given a well-prepared performance until well after his death, when Franz’s brother Ferdinand showed the score to Robert Schumann in 1838. Mendelssohn directed a performance of the entire work the following year in Leipzig. Many orchestras of that time found the work extremely difficult, and sections of it elicited laughter from the performers.

Nevertheless, the symphony has many remarkable features. It often vacillates between major and minor keys—it might even be thought of as being in C major and A minor. There are magnificent moments of dissonance that offset the lyrical melodies. A special place occurs in the second movement when chords pile up on each other, reaching an unprecedented clashing forte, followed by a long silence before the seemingly demoralized orchestra is able to re-enter*. Alternating choirs within the orchestra make interesting color shifts throughout the work.

The four movements are set up in the traditional pattern: 1. Andante-Allegro; 2. Andante con moto (beginning as a determined march); 3. Scherzo, Allegro vivace, and Trio; 4. Finale, Allegro vivac

Nevertheless, the symphony has many remarkable features. It often vacillates between major and minor keys—it might even be thought of as being in C major and A minor. There are magnificent moments of dissonance that offset the lyrical melodies. A special place occurs in the second movement when chords pile up on each other, reaching an unprecedented clashing forte, followed by a long silence before the seemingly demoralized orchestra is able to re-enter*. Alternating choirs within the orchestra make interesting color shifts throughout the work.

The four movements are set up in the traditional pattern: 1. Andante-Allegro; 2. Andante con moto (beginning as a determined march); 3. Scherzo, Allegro vivace, and Trio; 4. Finale, Allegro vivac

Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 "The Great"

I. Andante - Allegro ma non troppo

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

I. Andante - Allegro ma non troppo

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 "The Great"

II. Andante con moto

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

II. Andante con moto

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 "The Great"

III. Scherzo. Allegro vivace

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

III. Scherzo. Allegro vivace

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 "The Great"

IV. Finale. Allegro vivace

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

IV. Finale. Allegro vivace

Christoph von Dohnányi | The Cleveland Orchestra

*I was at a Severance Hall performance of this symphony directed by Christoph von Dohnanyi some years ago. It’s one I’ll never forget, and I have not yet heard any other performance bringing so much power to this moment! At this climactic moment, Dohnanyi built up the orchestra not just to a fortissimo, but to an astonishing fortississimo—the fullest volume possible among the performers—and let the ensuing silence linger seemingly forever. The slow, timid re-entry (as I remember it) consisted of a stunned-sounding string quartet, only gradually adding more instruments and slowly returning to the prescribed tempo. It made me think that at that moment Schubert had encountered the reality of his illness and its inevitable consequence. The “merry” little melody that followed was just his “whistling in the dark”…

Judith Eckelmeyer © 2023

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.