- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

Mozart's Don Giovanni

by Judith Eckelmeyer

(GRACE WOODS MUSIC SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2022)

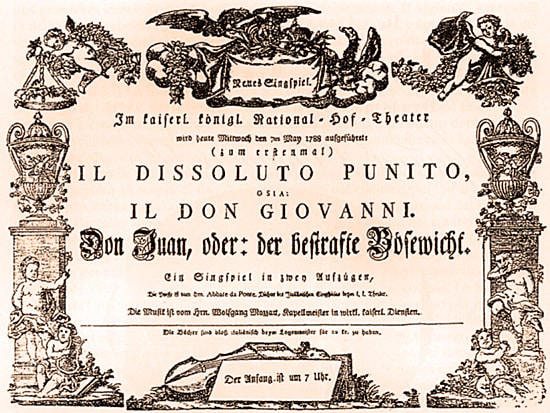

Mozart completed Don Giovanni, his second opera with the librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749-1838), in 1787, a year after the successful masterpiece The Marriage of Figaro. Unlike Figaro, however, Don Giovanni was written for and premiered in Prague, not Vienna. Mozart had close connections to Prague, and the city itself had quite a history of people such as John Dee (1527-ca. 1609) practicing in occult studies (particularly alchemy). Perhaps for that reason, Da Ponte’s libretto and Mozart’s setting of it ended with Don Giovanni’s mysterious demise. When the opera was finally presented in Vienna the following year, an additional finale was added after Giovanni’s demise to bring a rational conclusion to the stories not of Giovanni but of all the other major characters with whom Giovanni had interacted in the course of the opera. Today, this Viennese version is almost always the one to be seen in performances.

Da Ponte had adapted an old story written between 1615 and 1630 by the Spanish monk Tirso de Molina. There are some partial predecessors to Tirso’s work, and several prior to Da Ponte’s, including one by Molière, and numerous successors to Da Ponte’s across Europe and into the 18th century. There are also numerous commentaries and analyses of the opera well into the 20th century, including by psychoanalyst Otto Rank and theologian Søren Kierkegaard.

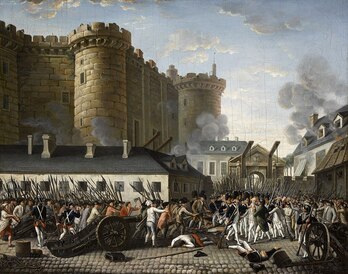

But leaving those aside, I think it’s important to point out that Figaro and Giovanni appeared within 6 years of the start of the French Revolution, an event that brought to a head the increasing unrest in Europe over the inequities of society under the rule of unrestrained hereditary monarchs. Both operas treat societal problem with both deeply serious tone, related to the Opera Seria, and comic or buffoonish elements, derived from Opera Buffa, the comic operas of the time.

Of the two operas, Don Giovanni is considerably the darker. The principal character, a nobleman, is the antithesis of all that is presumed to be noble, yet he is, according to some, “heroic” in his determination to remain “free” and unfettered by either societal or religious conventions. He says he is nothing without women, and his hubristic assumption of unchallenged privilege to assault them (even, as his servant Leporello comments, just “to add them to the list”) is matched by his disdain for his victims’ circumstances and feelings of anger and betrayal. His own pleasure is his measure of success. (Ironically, he is shown in the course of the opera to be impeded and frustrated in his attempts to seduce Anna and Zerlina.) To add insult to injury, Giovanni evades capture by his human would-be avengers. Only with the intervention of a deus ex machina, a device borrowed from Opera Seria, could the miscreant be stopped. Thus, while the story is rooted in the troubled reality of the time, it incorporates the supernatural aspects of the highly formal Opera Seria.

While Da Ponte’s text contains pointed, scathing, cynical and sarcastic comments directed toward Giovanni by the other characters, Leporello in particular, Mozart’s opinions conveyed through the musical setting of these comments is generally much subtler. It usually lies in the delivery of the passages by the singers of the respective roles and their action on stage to convey the acerbic intent of the words. However, Mozart’s own authentic contribution to the scorn heaped on Giovanni appears in the three pieces with which a small ensemble serenades their master while he is having dinner in the opera’s finale. Each piece is an aria that originated in a very popular opera around the time Mozart was composing Don Giovanni, and the text of each of the arias would have been well known to the audience; Mozart took the third of them from his own The Marriage of Figaro of the previous year. (Leporello says he knows the tune “only too well”!) And in each case, the texts of these pieces seen in the context of Giovanni’s behavior carry dire warnings of what was about to befall him. Of course he was only superficially aware of the music and didn’t recognize any the implied warnings, but Leporello did!

THE CHARACTERS IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE:

Leporello: baritone, Giovanni’s servant who tries numerous times to rein in his scandalous behavior.

Donna Anna: soprano, a noblewoman, Giovanni’s assault on whom occurs as the opera begins.

Don Giovanni: baritone, a “noble”man who tries to seduce anything in skirts.

The Commendatore (Commander): bass, a nobleman, Anna’s father who comes to defend her and in the process is killed by Giovanni in a duel.

Don Ottavio: tenor, a very idealistic, but not very practical, nobleman who patiently remains engaged to Anna.

Donna Elvira: soprano, a noblewoman from another city, previously seduced and abandoned by Giovanni; she wants him to repent in the worst way!

Zerlina and Masetto: a peasant couple celebrating the eve of their wedding. In some ways each is both naïve and very wise; Masetto especially is suspicious of Giovanni’s motives from the start.

The Memorial Statue of the Commendatore: bass, who by supernatural means communicates with Giovanni, who invites him to dinner. The statue arrives, to the horror of Leporello and astonishment of Giovanni.

Leporello: baritone, Giovanni’s servant who tries numerous times to rein in his scandalous behavior.

Donna Anna: soprano, a noblewoman, Giovanni’s assault on whom occurs as the opera begins.

Don Giovanni: baritone, a “noble”man who tries to seduce anything in skirts.

The Commendatore (Commander): bass, a nobleman, Anna’s father who comes to defend her and in the process is killed by Giovanni in a duel.

Don Ottavio: tenor, a very idealistic, but not very practical, nobleman who patiently remains engaged to Anna.

Donna Elvira: soprano, a noblewoman from another city, previously seduced and abandoned by Giovanni; she wants him to repent in the worst way!

Zerlina and Masetto: a peasant couple celebrating the eve of their wedding. In some ways each is both naïve and very wise; Masetto especially is suspicious of Giovanni’s motives from the start.

The Memorial Statue of the Commendatore: bass, who by supernatural means communicates with Giovanni, who invites him to dinner. The statue arrives, to the horror of Leporello and astonishment of Giovanni.

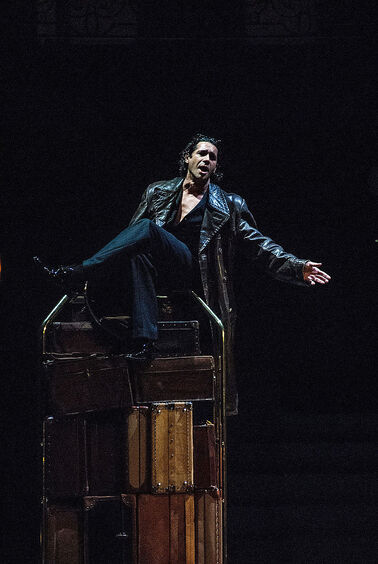

Mozart's Don Giovanni complete opera with English subtitles. Zurich 2001 production

Don Giovanni, Rodney Gilfry | Leporello, László Polgár | Donna Anna, Isabel Rey | Don Ottavio, Roberto Saccà | Donna Elvira, Cecilia Bartoli | Zerlina, Liliana Nikiteanu | Masetto, Oliver Widmer | Commendatore, Matti Salminen

Conductor, Nikolaus Harnoncount | Director, Brian Large

Don Giovanni, Rodney Gilfry | Leporello, László Polgár | Donna Anna, Isabel Rey | Don Ottavio, Roberto Saccà | Donna Elvira, Cecilia Bartoli | Zerlina, Liliana Nikiteanu | Masetto, Oliver Widmer | Commendatore, Matti Salminen

Conductor, Nikolaus Harnoncount | Director, Brian Large

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.