- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

GRACE WOODS MUSIC SESSION: JUNE 14 & 16, 2021

HAYDN’S SYMPHONY 45, “FAREWELL”

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN: 1732-1809. Brief Biography:

In his lifetime, he was at his maturity certainly the most famous and honored living composer, known across Europe for the large number and exceptional quality of his compositions. In our time, we recognize that he almost single-handely shaped the direction of the string quartet, piano sonata, and symphony as we know them, and his contributions to the literature of Mass settings and oratorio in the late 18th century are invaluable. As we shall see, the epithet “father of the symphony” was not devised for him in vain.

Haydn’s early music training began when he was 8 years old and was accepted as a choirboy at the Cathedral of St. Stephen in Vienna. He remained with the choir for some time even after his voice changed. He began to earn a living as a freelance musician then, singing in the court choir and teaching. After some early efforts at composition he began to study more systematically with the composer Nocola Porpora. He found his first patron in 1759 while under Porpora’s aegis: Count Morzin, who lived in Vienna and also spent a lot of time in Bohemia. It appears that Morzin ran out of money soon thereafter, and Haydn began working for the Esterházy family perhaps on the side. He formally entered the employment of the Esterházy family in 1761.

At the Esterházy palace in Eisenstadt (then in Hungary), Haydn was charged with extraordinary responsibility and answerable directly to Prince Paul Anton in everything except choral music. (For this he was the subordinate of the senior music director, or Kapellmeister, Gregorius Werner.)

Among the first works Haydn wrote for the Esterházy court were three symphonies, in D major (no. 6), C major (no. 7), and G major (no. 8), all in 1761, which he himself titled “Le matin (Morning)”, “Le midi (Noon)”, and “Le soir (Night)”. The titles are noteworthy because at the time most symphonies were identified simply by their key (rarely a number). The titles suggest that these are “program” symphonies, describing something relevant to those times of day. The three symphonies are not at all similar in their structure; further, they contain features left over from other genres and earlier times, such as interconnected movements, instrumental recitatives, seemingly whimsical arrangements of tempos and styles, and a continuo. Haydn’s orchestra had only 10-15 players at the time.

Symphony 6 has the four movements of a classical symphony, but its “throwback” feature is its solo instruments—violin and cello soloists in contrast to the body of strings, plus a flute, 2 oboes, bassoon, and 2 horns. The first movement opens slowly with a “sunrise” before going on to the main allegro portion. The second movement is primarily a duet between the soloists (the continuo is evident), essentially forming a concerto-grosso. The third movement is a minuet reintroducing the winds into the mix; the trio, in minor, features a bassoon solo and the solo cello. The last movement, Allegro, features the ensemble and all the individual instruments.

Symphony 7, for strings (and continuo), 2 flutes, oboe, bassoon, 2 horns and strings, is in five movements. The first begins with a regal introduction, befitting royalty (a compliment to his new employer?), then goes on to a vigorous Allegro. The second movement is a dramatic, minor-key recitative (textless) for violin with orchestra accompaniment. This leads to a lovely, slow aria-like movement featuring solo violin and cello. After a minuet movement, the Allegro finale features soloist’s moments (as did Symphony 6).

Symphony 8, for strings (and continuo), flute, 2 oboes, bassoon and 2 horns, is in the more recognizable symphonic structure of the late classical era: four movements, Fast, Slow, Minuet/Trio, and Fast. The point of greatest interest is the final movement, entitled “La tempesta”—the storm. Patterns in the music suggest rainfall, lightning, and thunder, but these are genteel, a passing shower rather than furious gale.

It is interesting to compare this “storm” at the end of Symphony 8 with the heightened effects of true Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), which one can hear in the first movement of Haydn’s Symphony 45 (“Farewell”, 1772). In Symphony 8, Haydn had not yet gathered all his forces of dynamic and melodic extremes, intense dissonance, and struggling agitation. I think he had yet to be exposed to the music of Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck’s ballet Don Juan (1761) and music of other dramas by Gluck which preceded the “Farewell”, for in these genres Gluck was free to invent whatever musical effects promoted the drama. It appears that once Haydn embraced the potential in dramatic music, he absorbed it into the symphony and transformed it into its powerful voice for the late Classical era, and he and Mozart (and others) made famous use of the style.

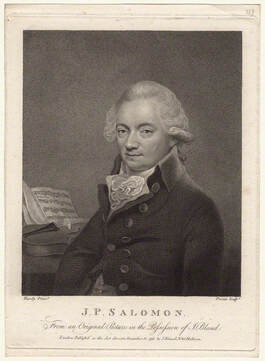

Only a year after Haydn arrived at Eisenstadt, Paul Anton died and his music-loving brother Nikolaus succeeded him as Haydn’s patron and employer. Haydn served Nikolaus for nearly 30 years thereafter. In 1779 Haydn was contractually freed from the obligation to compose only for Nikolaus, and he began to accept commissions and publish a good portion of his music. His reputation grew enormously throughout Europe as he continued to compose. The last symphony Haydn wrote under Nicolaus’s employ was his 92nd, in G major, in 1789. By this time Haydn was the most famous composer in the world, so news of his patron Nikolaus’s death on September 28, 1789, reached every major music center. Shortly thereafter, Johann Peter Salomon, a violinist and concert manager in London, approached Haydn in Vienna to come to England; and Haydn, free of any other obligations, accepted.

He made two visits to England (1791-2 and 1794-5), where he was feted and honored by an adoring public. Respect for him extended even to the often-curmudgeonly halls of academe, and in 1791 he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree at Oxford University. At the second of three commemorative celebrations of this event, the Symphony in G, no. 92, was performed, and thus it received the nickname “the Oxford symphony”. And by the way, while in England Haydn still continued to compose symphonies – twelve of them over the two visits – which are known as the “Salomon symphonies”, or as a group the “London symphonies” (his last, no. 104, is itself called “the London Symphony”).

The 92nd symphony, “Oxford”, is a wonderful example of Haydn’s mature mastery of the genre. It employs flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets and timpani—a significant expansion over the 6th, 7thand 8th symphonies. The Esterházy orchestra would have provided probably 25 players for the “Oxford”, but in England there well may have been more strings performing. In the “Oxford” symphony Haydn reveals a depth of expressive devices and the amazing paradox of greater complexity of construction in a greater simplicity of sound. Melodies are full and memorable, yet there is wonderful ingenuity in the harmonies and in the ingenious ways material is extended and developed, sometimes with Haydn’s inimitable sense of humor.

TWO TERMS RELATED TO HAYDN’S SYMPHONIES:

“Sturm und Drang” (“Storm and Stress”) was a distinctive musical style that emerged in the operatic works of Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck in the early 1760s, and thereafter taken into the musical language of Haydn, Mozart, and later composers. It is characterized by minor key harmonies, much agitation, sudden changes in extremes of dynamics, pungent dissonances, and extraordinarily large-range melodies.

“Sturm und Drang” (“Storm and Stress”) was a distinctive musical style that emerged in the operatic works of Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck in the early 1760s, and thereafter taken into the musical language of Haydn, Mozart, and later composers. It is characterized by minor key harmonies, much agitation, sudden changes in extremes of dynamics, pungent dissonances, and extraordinarily large-range melodies.

“Galant” style was the “normal”, standard musical expression of the time: regular phrases, pleasing melodies and harmonies, non-jarring dynamic changes, major keys, clear structure of compositions. It was so universal that we might experience it as “wallpaper” music today.

BACKGROUND TO THE “FAREWELL” SYMPHONY:

Nikolaus Esterházy “the Magnificent”, Haydn’s patron for nearly 30 years, enjoyed living at his hunting lodge near the Neuseidlersee on Hungary’s border with Austria; during Haydn’s time of employment, he replaced the lodge with an elaborate palace, called Esterháza, and spent as much as 10 months of the year there. Haydn and his musicians as well as his household staff were obliged to attend him there without their wives. In the fall of 1772, Nikolaus stayed much longer than usual and the musicians begged Haydn to intercede with him to return to Eisenstadt. Haydn’s tactic was to write a symphony which would make the case clear to Nikolaus. This was the “Farewell” symphony, No. 45, in F-sharp minor.

Nikolaus got the message—the prince and his retinue returned to Eisenstadt the day after the symphony’s performance.

Nikolaus Esterházy “the Magnificent”, Haydn’s patron for nearly 30 years, enjoyed living at his hunting lodge near the Neuseidlersee on Hungary’s border with Austria; during Haydn’s time of employment, he replaced the lodge with an elaborate palace, called Esterháza, and spent as much as 10 months of the year there. Haydn and his musicians as well as his household staff were obliged to attend him there without their wives. In the fall of 1772, Nikolaus stayed much longer than usual and the musicians begged Haydn to intercede with him to return to Eisenstadt. Haydn’s tactic was to write a symphony which would make the case clear to Nikolaus. This was the “Farewell” symphony, No. 45, in F-sharp minor.

Nikolaus got the message—the prince and his retinue returned to Eisenstadt the day after the symphony’s performance.

SOME FEATURES OF THE “FAREWELL” SYMPHONY:

- Scored for 2 oboes, 2 horns, 1 bassoon, violins, violas, cellos, basses.

- F-sharp minor was a very unusual key at that time; Haydn had to have new crooks made for the natural horns so they could play in tune in this odd key.

Although there are the usual four movements (fast, slow, minuet, fast), they don’t proceed in quite the usual manner; Haydn used this variant to get his message across. There are distinct abberations in the first and last movements.

- Scored for 2 oboes, 2 horns, 1 bassoon, violins, violas, cellos, basses.

- F-sharp minor was a very unusual key at that time; Haydn had to have new crooks made for the natural horns so they could play in tune in this odd key.

Although there are the usual four movements (fast, slow, minuet, fast), they don’t proceed in quite the usual manner; Haydn used this variant to get his message across. There are distinct abberations in the first and last movements.

Haydn's Symphony No. 45

Sinfonia Rotterdam | Conrad van Alphen, Conductor

Sinfonia Rotterdam | Conrad van Alphen, Conductor

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2021

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.