- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

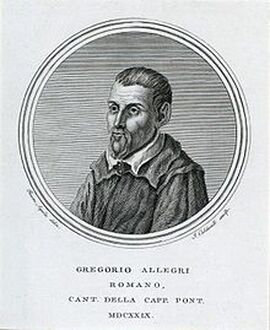

Gregorio Allegri: Miserere

Essay on Gregorio Allegri's Miserere

by Judith Eckelmeyer

Gregorio Allegri (1582-1662) spent the bulk of his life as a chorister, music director, composer, and priest in Rome. The most important part of his career came after 1629 when he served as a singer in the papal choir. During this time he created a number of motets, the most famous of which is his “Miserere”, a setting for nine voice parts of the first twenty verses of the penitential Psalm 51. The work became a customary component of the Tenebrae service and was performed on Wednesday and Friday in Holy Week in the Papal (Sistine) Chapel.

It is worth remembering that in the Papal Chapel only male singers performed (with no instrumental accompaniment). From the mid-17th century on, the motet’s fame enticed editors and composers to introduce changes into the motet’s performing forces and content, eventually scoring the work for women as well as men.

The musical forces in the “Miserere” are organized into two choirs. Choir I is a full ensemble comprised of two soprano parts, altos, tenors, and basses presenting simple, fairly static melodies harmonized in chords, with brief moments in chant style and occasional very limited counterpoint. Choir II is a solo ensemble of two sopranos, alto, and bass, who introduce more active, typical early Baroque rhythms as well as extreme ranges—up to a high C for the top soprano. Choir I and Choir II alternate in the presentation of harmonized psalm verses; between the ensemble verses, men chant a verse in unison. Thus, as the motet progresses, there are three sonorities in regular rotation: Choir I’s multi-voice ensemble in harmony, followed by unison chanting by men, then Choir II’s four soloists singing more actively in harmony; then plainchant again, then the large ensemble, and so on. This pattern continues till the middle of the psalm’s 20th verse, at which point the two choirs join into a nine-part ensemble to complete that verse and end the motet. The simple harmonic beauty, the fascinating alternation of performing sonorities, the breathtaking ornamental working of the soloists’ ensemble, and the magnificent nine-voice conclusion combine with the passionate psalm text to form an extraordinary experience for those who hear this motet.

So striking was the impact of Allegri’s “Miserere” that it was kept in strictest security for many decades. The 18th–century historian Charles Burney reported that no one could copy or take parts out of the chapel under pain of excommunication! (It turns out that several copies were made and given out with official imprimatur; one even reached London, where it was printed in 1771.) As Otto Jahn tells us, no less a figure than the 14-year-old Mozart, in Rome with his father for Holy Week, heard the work at the Wednesday service and afterward wrote it down from memory, then made a few corrections at the Friday performance. Although papa Leopold was at pains to keep Mozart’s feat a secret, word got out, and Wolfgang was obliged to perform the “Miserere” for the astounded Papal singer Christofori. Mercifully, he was never chastised for his offence to the church; Jahn reports that he was honored for his feat of memory.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2017

The musical forces in the “Miserere” are organized into two choirs. Choir I is a full ensemble comprised of two soprano parts, altos, tenors, and basses presenting simple, fairly static melodies harmonized in chords, with brief moments in chant style and occasional very limited counterpoint. Choir II is a solo ensemble of two sopranos, alto, and bass, who introduce more active, typical early Baroque rhythms as well as extreme ranges—up to a high C for the top soprano. Choir I and Choir II alternate in the presentation of harmonized psalm verses; between the ensemble verses, men chant a verse in unison. Thus, as the motet progresses, there are three sonorities in regular rotation: Choir I’s multi-voice ensemble in harmony, followed by unison chanting by men, then Choir II’s four soloists singing more actively in harmony; then plainchant again, then the large ensemble, and so on. This pattern continues till the middle of the psalm’s 20th verse, at which point the two choirs join into a nine-part ensemble to complete that verse and end the motet. The simple harmonic beauty, the fascinating alternation of performing sonorities, the breathtaking ornamental working of the soloists’ ensemble, and the magnificent nine-voice conclusion combine with the passionate psalm text to form an extraordinary experience for those who hear this motet.

So striking was the impact of Allegri’s “Miserere” that it was kept in strictest security for many decades. The 18th–century historian Charles Burney reported that no one could copy or take parts out of the chapel under pain of excommunication! (It turns out that several copies were made and given out with official imprimatur; one even reached London, where it was printed in 1771.) As Otto Jahn tells us, no less a figure than the 14-year-old Mozart, in Rome with his father for Holy Week, heard the work at the Wednesday service and afterward wrote it down from memory, then made a few corrections at the Friday performance. Although papa Leopold was at pains to keep Mozart’s feat a secret, word got out, and Wolfgang was obliged to perform the “Miserere” for the astounded Papal singer Christofori. Mercifully, he was never chastised for his offence to the church; Jahn reports that he was honored for his feat of memory.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2017

The Choir of Claire College, Cambridge, Timothy Brown

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.