- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

The Legacy of Christian Rosenkreuz in Mozart's "Magic Flute"

Lecture presented by Judith Eckelmeyer at the 1991 Magic Flute Symposium, Oberlin College, OH

“The origin of Die Zauberflöte,” wrote Alfred Einstein, “like that of the Requiem, is covered with a web of legends.” Einstein was referring to stories about the chain of events which led to the production of the opera. But in another sense his comment strikes at the heart of the opera’s complexity, its extraordinary position in the genre as a puzzle whose meaning many have tried to solve and few have approached with convincing results. Indeed, the origin of the work is covered with a web of legends, and by this I mean the heterogeneous resources or source works which have lent their services to the creation of the plot of libretto of The Magic Flute.

Setting aside for the moment the obvious musical materials which fed into Mozart’s composition of this opera, and considering the literary and historical/cultural materials that have been traced in the plot and libretto, we find an extraordinary layering of thematic elements reflecting a wide spectrum of late 18th-century European culture. Consider, for instance, the now-accepted literary and thematic sources of the work: Sethos, a pseudo-biography of an Egyptian prince trained for governing by his entry into a mystery religions; Wieland’s collection of fairy tales, Dschinnistan, in which is included “Lulu, or The Magic Flute,” with its fairy queen and her daughter to be rescued from an evil being by a prince equipped with a flute capable of governing human emotions; the myths of Isis and Osiris and Orpheus, sources for the mystery religions of Egypt. Superimpose on this complex a series of cultural or historical factors which colored the life of German-speaking Europe in the late 18th century: the philosophical flourishing of the enlightenment, which espoused rationality and intellectual understanding as the chief attribute of the human condition; the widespread secret societies of the time, the Illuminati and particularly the Freemasons, with their number symbolism and symbolic rituals—in some cases involving initiation practices for both men and women—to which not only many of the nobility belonged but which also attracted the lower and middle-class; alchemical lore, with its focus on the action of elements, purification and the rise of modern concepts of chemical and physical action and reaction; the death of a major European leader, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, and the succession of his brother, the more conservative Leopold, to the throne of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire only one year prior to the year of The Magic Flute. As each fragment of this wide diversity of literary, cultural and historical factors has come to light, there has been general acceptance of it as valid to the history of this opera. Such breadth of feeders to the opera suggests that the work’s “meaning”, or message was in its own time accessible on many levels to an audience representing all sectors of society. However, it might be argued that if there are already so many acknowledged sources and “levels” of approach to the Magic Flute, we may not yet have at our disposal all the important information necessary to understanding this opera. There may in fact be some sources that have not yet been recognized. I suggest that this is indeed the case; that an important ingredient has as yet not been fully examined among the resources from which the opera’s creators drew. This “new” resource is Rosicrucianism, and I intend to examine not only the nature of the movement but its “gifts” to the plot and libretto of The Magic Flute.

A connection between The Magic Flute and Rosicrucianism has already been marginally remarked by Jacques Chailley, in The Magic Flute: Masonic Opera, and Alfons Rosenberg, in Die Zauberflöte: Geschichte und Deutung von Mozarts Oper. I have qualified their references to Rosicrucianism as “marginal” because they are extremely limited in their content. Chailley makes only one passing reference to the Rosicrucians as one of the secret societies at the time; Rosenberg discusses the early history and documents of the Rosicrucian movement but does not offer any specific connections between these and the opera. Furthermore, Rosenberg’s monograph still exists only in German; it has evidently not come to the attention of authors of main-stream music history texts even though it has been cited in some highly significant articles in recent years. Nevertheless, Rosenberg’s attention to the Rosicrucians points to their origins in the early 17th century, and he clearly identifies the principal documents of the movement as relevant to the plot, albeit in the most general way.

I believe that these early Rosicrucian documents are far more significant to the opera’s plot and libretto than even Rosenberg has indicated, and by examining them and the Rosicrucian movement of the early 17th century in some detail, I believe we shall understand more clearly the opera’s content and an as yet unexamined purpose or meaning to it. We shall be able to account for a number of important details in the opera not touched by its known sources: The intricate history which we learn about Pamina’s family; the trails of Pamina at the hands of the Moor, Monostatos; Papagena’s peculiar appearance as an old woman throughout most of her stage activity; and a host of clearly symbolic details throughout the opera. More generally, I believe that we shall see a strong connection of Rosicrucianism with a thread of religious history that connects the early 17th-century with the middle- and late 18th century, particularly in the little-considered relationship of the Pietists and the Moravian Brethren to the culture of Mozart’s time, and ultimately to The Magic Flute.

The term “Rosicrucian” derives from the name of a fictitious and allegorical figure, Christian Rosenkreuz, who was to have lived from 1378 to 1484; a philosopher and deeply religious Christian, he is described as having followed scientific and spiritual paths toward a more perfect knowledge of God and Jesus Christ. His story relates that he travelled widely in his search for learning, and established an association with three other seekers with whom, through example and through study and writing, he might bring about the “reformation of the whole world.” Eventually this small core grew to a larger Order whose members helped heal the sick and travelled extensively to increase their own knowledge. With the death of Rosenkreuz, the Order continued on in a pattern of activities and convocations established by its founder, but these were carried on in a private, irregular and unobtrusive manner over a widely scattered territory, awaiting world-wide conversion to their religious fervor. Thus the Order described itself as “moveable and invisible.” This fictitious Rosenkreuz and the order of reformers were the supposed antecedents to an undefined group of visionaries in the early 17th century who, through their publications about Rosenkreuz and his Order became referred to as “Rosicrucians.” The effect of their writings was broad enough to suggest that their views concretized a rather widespread movement which, although generally localized in Western Germany, became a very real source of concern in other parts of Europe as sympathetic publications appeared in those regions.

There is some disagreement about the meaning of the name Rosenkreuz. Traditionally it is translated as “rose cross,” but there is reason to believe that it originated from a subtler alchemical tradition in which “ros’ meant “dew,” a solvent of gold, and the cross referred to light. This interpretation points to the fact that the “Rosicrucian” movement rested largely on symbolic language, and that the movement itself, in its early 17th-century manifestation, rather than the personages of Christian Rosenkreuz and his followers, was the historical reality with which we must be concerned. Indeed, the movement participated in a well-established mystical tradition, of which, from the end of the 15th century onward, Paracelsus, John Dee, Robert Fludd, Michael Maier, Jokob Boehme, Francis Bacon and Elias Ashmole were famous exponents. However, works of such diverse thinkers such as the 14th-century philosopher Ramon Lull, and the late 17th-century Leibniz, among others, are imbued with symbols, ideas, and turns of phrase, suggesting that early 17th-century efflorescence of documents was in some fashion a response to an intensification of interest in a relatively long and enduring concern with these matters. The language and theory that mark this tradition throughout its history are rich in alchemical, cabalistic and hermetic terms and principles.

The Rosicrucian movement produced public evidence of its existence from about 1610-1623 in a group of publications related to the founding and philosophy of the Order (we shall discuss these in more detail below). In these documents it was clear that at the root of the movement was an attempt through symbolic language both to articulate and to encourage a spiritual awakening in Europe, especially Protestant Europe, in an effort to effect a return to a simpler, more heartfelt practice of Christ’s teachings and to counteract the secularization of the European community at large.

A principal scholar of the 17th-century Rosicrucians, Frances Yates, explored the Hermetic tradition and brought a new aspect of late Renaissance philosophical life to light. In discussing what she calls the “Rosicrucian Enlightenment,” Yates showed that the 17th-century “Rosicrucians”—those writers espousing the tenents of Father Rosenkreuz’ Order—never formally organized themselves as a society nor fully identified themselves to the public. The content of the Rosicrucian writings touches not only religious life but social and political reform as well. One can infer through them a list of well-placed theologians, publishers, scientists, philosophers and educators who supported and contributed to this “moveable and invisible college” with the prospect of effecting a unified Protestant front, symbolized in the marriage of the Protestant Frederick V, Elector Palatinate, to Elizabeth, daughter of England’s James I; this union would join not only England and north Germany but also, later, Bohemia, where Frederick was elected king, against the extension of Roman Catholic Hapsburg power and the then-ascendent Counterreformation among the Jesuits. Yates shows that a great many of the intellectuals associated with Frederick’s court were steeped in the symbolism of alchemy and hermeticism with which the Rosicrucian literature abounds, and that in their marriage, Frederick and Elizabeth had provided for this circle of “Rosicrucians” the living model for what otherwise would have been merely an abstract mystical symbol of the movement’s religious/political aspirations.

The core of the Rosicrucian philosophy resides in three principal documents, attributed to Johann Valentin Andreae, theologian and son of a noted Lutheran pastor; these documents give the central myth and symbolism of the movement: the Fama Fraternitatis, 1614, telling the life history of Christian Rosenkreuz and the founding of the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross among his faithful followers; the Confessio Fraternitatis, 1615, the creed of the Brotherhood; and theChymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosenkreuz (the Chemical—i.e., Alchemical—Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz), 1616, Christian Rosenkreuz’s experiences at a seven-day festival celebrating the wedding of a royal couple. In addition to these, Andreae’s own later utopian book, Christianopolis, 1624, and a number of open letters either praising or condemning the “principles” and philosophy propounded in the Rosenkreuz adventures constitute the main bulk of literature in this Rosicrucian “movement.” With the beginning of the Thirty-Years’ War in 1618, Andreae published what many historians consider to be recantations of his earlier enthusiasm for the Rosicrucian ideals. On the continent, “movement” itself disappeared from public view for about 150 years, as the general tenor of the times made occultism and mysticism suspect, and as the formerly Protestant area in which the Rosicrucian literature was published became Catholic-dominated territory. It is commonly accepted however, that the tradition of Rosicrucian philosophical writing continued in England in works of Elias Ashmole, Thomas Vaughan and others [RE, 177-205, esp. 193ff, for example.]

A resurgence of interest in “Rosicrucianism” occurred in the mid-18th century, concomitant with an increasing expression of the anti-rational in many spheres: sentimental literature, Germany’s Empfindsamkeit (sensitivity) and Sturm und Drang(storm and stress); Mesmer’s experiments with the world of mysterious, unseen forces in such things as magnetism and its effects on human beings; Swendenborg’s mystical writings in the vein of the 17th-century Jacob Boehme; Cagliostro’s quasi-Masonic excursions into occult lore; the highly emotional “Sifting Time” of the already pietism-based Moravians. All were products roughly of the mid-century rejection of purely intellectual, logical and scientifically quantifiable existence. A formal organization of “Rosicrucians” was founded in 1777. Called the “New Order of the Rose- and Golden Cross,” it drew on the principal 17th-centiury documents, the Fama and Confessio, as their source of authenticity; their mystical and alchemical bent was clear and grew from the “tradition” of their namesakes. A more politically motivated sister-organization, the Illuminati, attempted to weld together two traditions, the mystical as evidenced in the Rosicrucians, and the rational as manifested in the “English-based Blue-lodge on St. John Masonry. The Illuminati claimed membership of a number of artists, writers, and philosophers who were first of all Masons and many of whom had also participated in the Order of the Rose- and Golden Cross. The cross-fertilization of these organizations in Germany in the second half of the 18th century is a cultural phenomenon which accounted for a wide dissemination of commonly understood symbols and esoterica. Moreover, the Fama and the Confessio were available to the late 18th-century German reader, and the Chrmische Hochzeit was also known, if not in itself, then through its commentary the Elucidarius. This latter was among the works published and available in Vienna during the period of the “extended freedom of the press” (1781-1795), largely during the reign of Joseph II. [Wernigs.] As we shall see in a later chapter, both the Chymische Hochzeit and Campanella’s City of the Sun were also available in the court library at the time the opera was written – as were numerous other important works from this tradition.

The most extensive points of reference from this body of literature to The Magic Flute come from the Chymische Hochzeit and its commentary, the Elucidarius Major, oder Erleuchterunge über die Reformation der ganzten weiten Welt (The Great Elucidation or the Enlightenment concerning the Reformation of the Whole Wide World, 1617, and the somewhat later Christianopolis. The Chymische Hochzeit appears to be a source for two extensive elements in the opera, the concept or vision of an alchemical union or wedding; there are as well several other less extensive points in the plot, many of which relate to Papageno and Papagena. That the Magic Flute as a whole is an alchemical parable, or metaphor, had already been well established through the work of Dorothy Koenigsberger; the Hochzeit’s unquestioned use of the alchemical process to bring about the heirosgamos or sacred wedding, makes it a particularly strong paradigm for the opera’s theme of unifying Tamino and Pamina, and, in parody, Papageno and Papagena. However, it is of great importance to remember that the alchemical process and alchemical symbolism was being used in the 17th-century Rosicrucian movement, as a metaphor for spiritual and theological ideas and processes. We shall see that the 18th-century writers who borrowed the Rosicrucian stories and alchemical language may not have had the specifically Lutheran – or even Christian – meanings in mind when they applied them creatively, but rather saw them primarily as social and/or political terms. The “paganization” of the 18th century, a phenomenon of the “Enlightenment” [Peter Gay: The Enlightenment. An Interpretation: The Rise of Modern Paganism. N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 1966] may be seen in the workings and mythologies of Freemasonry, for example, and as convincingly as in the secular stylistic incursions in art works designated for church use – whether visual (Johann Baptist Zimmermann’s cherubic cupids in the churches of Bavaria and Swabia, for instance) or musical (Mozart’s amorous serenade as the “Et incarnatus” of the C-minor Mass).

Mozart's Mass in C minor, K427

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra | Eric Ericson Chamber Choir | The Monteverdi Choir

John Eliot Gardiner conductor | Miah Persson soprano

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra | Eric Ericson Chamber Choir | The Monteverdi Choir

John Eliot Gardiner conductor | Miah Persson soprano

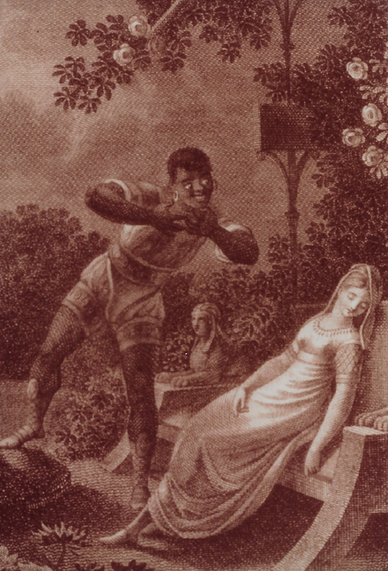

The Hochzeit’s story is told through the eyes of “Christian Rosenkreuz”, who has been summoned by a mysterious invitation to be a guest in the week-long celebration of festivities around the wedding of a young royal couple. The Elucidarius points out that the Hochzeit’s week-long celebration is a clear and unmistakable allusion to the Biblical creation of the world in 7 days – the appearance of a new world in 7 days. The 4th day of creation has significant symbols taken by Freemasonry: separation of the night from day; the creation of the stars; the creation of greater and lesser lights to rule day and the night for a sign and for seasons and years. If relevant to Freemasonry, however, the events of the Fourth Day are particularly significant with regard to The Magic Flute as well, as we shall see. According to the Elucidarius, the alchemical process illustrated in that day is “nigredo” – the post-putrefaction blackening of the substance undergoing transformation into gold. The day’s events fall into three parts: a seven-act play, termed a “comedy,” performed by students for the benefit of the court and guests, and the pre- and post-performance actions of Rosenkreuz and his associates in the royal court in relation to the bride- and groom-to-be. Both parts of the narration contain information which we may reasonably trace into the Magic Flute. In order to understand the link between the Hochzeitand the Magic Flute we shall examine the Hochzeit’s 4th-day events and then their corresponding manifestation in the opera, with points of theological or alchemical symbolism embodied in the story. [n.b. – Jung, Myst. 350: Nigredo causes melancholy and despair. Ibid., 422: Maier says “’wretchedness and vinegar’ stand for the melancholia of the nigredo…”]

Let us first consider the comedy which the students present to the court on the 4th day in the Hochzeit. This play concerns a young unnamed princess who is twice displaced from her home. The first time she comes as an infant to the court of an Ancient King to be raised through her childhood by him as the last remnant of a kingdom destroyed by the King of the Moors; the second displacement occurs when the Moor, described as “a black, treacherous fellow,” begins to plot against the Ancient King and is finally able to re-abduct the girl, and having done so, except for the deception of his own servants he would have slain her. The Ancient King raises a great army against the Moor under the leadership of a valiant, old Knight. The Knight rescues the princess from the tower where she is being held, and he reclothes her (a symbol of “putting on the new” or salvation). A platform is built and she is placed on it. Twelve royal ambassadors come by and the Knight tells everyone that the Ancient King has delivered the princess from death and allowed her to be royally brought up, even though she was not entirely well-behaved. Further, he has chosen her to marry his son, under certain conditions; the girl swears to observe these. The princess is restored to her former, lost kingdom, is crowned and escorted around it in joy. Ambassadors are presented to her; they see her glory and wish her prosperity. Eventually, though, she begins to look around “wantonly,” winking at the ambassadors and lords. The Moor, hearing of this, wants to make use of the “opportunity.” In the hands of a careless steward, the princess’ confidence in her fiancé wanes, and blinded by great promises, she submits to “the entire disposal of the Moor.” The Moor, who now has her “in his hands,” gains control of her kingdom and has her humiliated publicly. The Young King, her fiancé, hears of these events and with his father’s help tries to have her released from the Moor’s power, sending ambassadors to comfort her and tell her how inconsiderate she is. She, however, does not see the ambassadors but agrees to be the Moor’s concubine. The Young King learns of this and decides to do battle with the Moor. In the battle the Moor is wounded, but the Young King is thought to have been killed. Yet the Young King revives, releases the princess and places her in the care of his steward and chaplain, both of whom torment her. The Young King also hears of this and sends someone to “break the neck of the priest’s mightiness” and clothe the princess for her wedding. The final scene is of the bridegroom in great pomp, greeted with great solemnity by the bride. The audience, watching the spectacle at court, is moved to cheer the couple, symbolically congratulating the young royal couple in the audience. After taking a few turns around the stage the actors sing a 3-verse carol, extolling 1) the time of love and joy at the King’s wedding, 2) the beauty of the bride and her union with the King, and 3) the subduing of the parents and release of the bride, and the prospect of “thousands” arising and springing from her “own proper blood.”

Pamina’s story in The Magic Flute appears to parallel aspects of the student’s drama in the Hochzeit. Pamina is introduced indirectly when the audience learns in the opening scenes that the princess has been abducted from her mother, the Queen of the Night, by an “evil sorcerer,” Sarastro. Just before she actually appears on stage in I, xi, two slaves in her quarters within Sarastro’s palace comment gleefully on her recent escape from her overseer, a “merciless devil,” the Moor Monostatos; the slaves’ enjoyment of the news is abruptly reversed when they are commanded by Monostatos himself to bring chains, for he has recaptured the runaway. After this bold attempt to escape, Pamina, now on stage, subsequently defies the Moor and refuses to acquiesce to his forced attentions. Joined by the birdcatcher, Papageno, she attempts once again to escape but is interrupted by Sarastro’s arrival and his adamant refusal to let her go free. Throughout the rest of the opera, Monostatos’ attraction to Pamina impels him first to attempt to kiss her, and later to coerce her by threat to yield entirely to his love. [Hans-Albrecht Koch suggests another literary origin for Monostatos…] Pamina determines to refuse to submit to the Moor even at the risk of her own life, because she loves the prince Tamino. She even defies her own mother’s order to kill Sarastro when she learns that her father, dead since her early childhood, gave his symbol of authority to Sarastro who, she recalls, had always associated with wise, good, and understanding men. Sarastro saves Pamina from Monostatos’ attach and explains the principles of human concern and love which govern within the “sacred halls” and “sacred walls” of his realm. Distracted by confusion and despair over Tamino’s apparent coolness toward her, Pamina is about to commit suicide when three young boys intervene and tell her that Tamino actually loves her and is waiting for her. Reunited with the prince, Pamina endures the trials of fire and water and is shown the great revelation with him. In the final scene both she and Tamino appear in “priestly clothes” as the chorus of Sarastro’s community hail the initiates, thank Isis and Osiris, and proclaim, “Strength was victorious, and in reward, exalts beauty and wisdom with an eternal crown.”

Several commonalities between the Hochzeit drama and the opera are clear. Both heroines are abducted and fall under the domination of an evil Moor whose power includes sexual control and other forms of humiliation.

Each is finally “rescued” through the efforts of a young, loving prince and united with him in a kind of apotheosis at the end of the story. Both have the assistance of an older man whose authority is over a kingdom or community, and who have a significant paternal function toward the young prince. In both stories, the older men and the young princes are aligned with concepts of modesty, consideration, “goodness,” and the principal plot is the emergence of the princess from the shadow of impure love to be united with the prince in a pure love. The conclusion of both play and opera consists of a “choral” acclaim in three parts including references to a wedded royal couple, beauty, and an unending victory.

A particular point of correspondence between the Hochzeit drama and The Magic Flute concerns the idea with which the students’ play ends: the “chorus”’ wish that “thousands” will issue from the bride’s “own proper blood,” that the couple will, through generations, produce many descendants from the chosen wife, whose lineage (blood) is not only “correct” but “pure,” even “sanctified” as well. The parallel situation in the opera involves not only Pamina, who with Tamino will be responsible for a people they will govern, but also Papagena, the mate of the birdcatcher Papageno. Papagena first appears as an old woman and later undergoes a transformation into a young woman dressed like Papageno. (We shall see that this transformation bears upon our discussion of the Hochzeit in another way.) In their final scene, II, xxix, Papagena is presented to Papageno by the same boys who rescued Pamina from suicide. The couple sings a delightful duet in which they celebrate their union and look forward to the prospect of parenthood and “many, many Papagenos and Papagenas.” It would appear that the opera’s creators have taken the elements of the students’ 3-verse carol and divided them between the “serious” royal couple, Tamino and Pamina, and their shadow couple, the earthly comic pair Papageno and Papagena.

We have examined several points of positive correlation between the students’ drama and the Magic Flute, but there are several points of seemingly contradictory information which upon closer consideration show further points of correlation between the two works. For example, in the Hochzeit drama the princess’ behavior is specifically “wanton,” and when the Moor attempts to take advantage of this she actually becomes his “concubine.” In the opera, however, it is clear that Pamina’s actions are at no time “wanton” and that she utterly and consistently rejects Monostatos as a lover. On the other hand, Papagena might well have absorbed the element of “wantonness” in her guise as the old woman, for she is Papageno’s pursuer: in her first appearance on stage, II, xv, she offers Papageno a goblet of water, then chatters and banters with him, and finally explains that she has a boyfriend who is about ten years older than she, declaring that this boyfriend is Papageno himself! In a later scene, II, xxiv, she again showers Papageno with notice of her affection, suggesting that in return for his fidelity she will love him “tenderly” and tells him she wants to “embrace…caress…press [him] to [her] heart.” As with the situation around the final chorus, it appears that the opera’s creators have applied an element of the students’ drama more specifically to Papagena rather than to the principal royal character, Pamina. When we consider, however, that Papagena and Papageno are the shadow couple, the complimentary pair to Pamina and Tamino, the “contradiction” is no longer valid: Papagena as Pamina’s extension carries out the ignoble (not evil) aspect of the Hochzeit’s princess.

Another point of difference between the two works may be seen in the character of the drama’s Ancient King, the father of the Young King who rescues and marries the princess; in the Hochzeit drama, the Ancient King is the antithesis to the King of the Moors, under whose aegis the princess remains for a time. We would expect the Ancient King’s equivalent in the opera to be Sarastro, and yet Sarastro is neither Tamino’s father nor originally the Moor’s enemy; further, it is he who, by his own admission, abducted Pamina from her mother before the opera began. Early stage illustrations of the first Viennese production of the opera also indicate that Sarastro is not “ancient;” his goatee, finely trimmed moustache and shoulder-length loose-flowing hair are brown rather than grey, and his bearing is alert and vigorous from his place on a lion-drawn chariot. Nor is he styled as a “king;” the illustration shows him wearing a gold-colored hat which differs from the hats of his attendants, but there is no indication of a traditional crown or even a sceptre in his hand. (We will have more to say about this image of Sarastro later, in a consideration of its great relevance to the Rosicrucian movement.) Nowhere in the opera text is he referred to as “king.” Only two figures in the opera are designated “king:” Tamino’s father, whom the prince recalls when he tries to understand the mysterious reference to a “star-flaming queen,” I, ii; and Pamina’s father, whose “all-consuming sun circle” he gave to Sarastro rather than his wife, thus contributing to the Queen’s desire for vengeance, and whom Pamina remembers as associated with good, wise, and understanding men of Sarastro’s community, II, viii.

Is there a parallel to the drama’s Ancient King in the opera? We are perhaps able to see two instances of the Ancient King’s application in The Magic Flute. The character of Sarastro is vital here. First, he is the “heir” in an ethical bequest from Pamina’s father, indicating a philosophical or spiritual lineage rather than blood-line; having inherited the sun-circle, as a spiritual prince, he abducts Pamina from her mother to rescue the child from the Queen of the Night, “that woman [who] imagines herself great, and hopes through illusion and superstition to deceive the people and to destroy our secure temple” (II, i). There is some indication by the end of Act I that perhaps Sarastro had intended to win Pamina’s love for himself and to marry her, for he acknowledges her wish to escape and recognized that her affection is clearly directed toward a new “other:” “…without first pressing you I know more about your heart—you love another very much. I don’t intend to force you into love, but I am not giving you your freedom” (I, xvii). In this instance, Sarastro appears to parallel the role of the Young King in the Hochzeit, the rescuer of the princess and later “jilted” as a lover when the princess’ attention turns elsewhere (in the Hochzeit, to the Moor himself). However, an important transition occurs by the first scene of Act II in the opera. Sarastro now specifically identifies the prince Tamino as young and virtuous and chosen by the gods to wed Pamina; and significantly, Sarastro points out that “Tamino, the gracious youth, shall strengthen [the structure of the temple] with us, and as Initiate shall become the reward of virtue but the punishment of vice.” He is not only Pamina’s intended spouse but virtually the awaited reinforcement—cornerstone—of the community which Sarastro leads. From this moment, Sarastro assumes the function of a father to both Tamino and Pamina, much as the Ancient King did in the students’ drama when he raised the young princess in his court and then designated his son as the princess’ intended spouse.

The transfer of role-parallels from Sarastro to Tamino suggests a break in the plot’s continuity in a manner not previously considered in analyses of the opera. One might construct a cynical interpretation of the role-transfer by suggesting that the opera’s authors in fact deny the validity of a non-royal partner for the princess; but this argues against everything that the opera’s overt ethics proclaim: equality based on character and the quality of the heart rather than on blood lineage. The more consistent reading is that the opera’s authors completely discounted the issue of royalty and were intending to communicate a model for gracious acceptance of change—be it the union of a people with the “proper” political system or the fulfillment of a “true-love” bond. This interpretation is given credence by the fact that a similar thread occurs in La Clemenza di Tito, the other opera Mozart was writing while he composed The Magic Flute: the title character, like Sarastro, expects to marry a worthy woman but finally concedes his right to marry her when he realized how deeply she loves one of his good friends. Both Tito and The Magic Flute were written at the time of governmental transition, when Joseph II’s successor Leopold II was being crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. And if we recall the structural aspects of The Magic Flute and their link with the dialectic process, the aspect of transfer from Sarastro to Tamino becomes not just believable but inevitable.

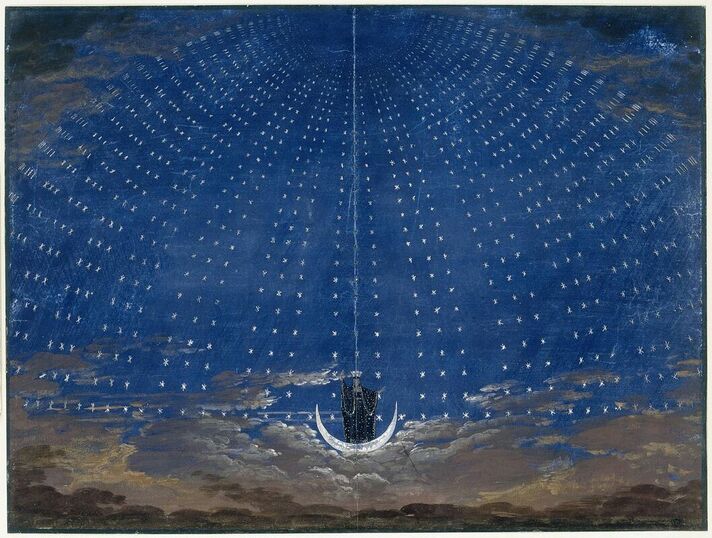

While preceding points of comparison between the Hochzeit and The Magic Flute are drawn from the students’ drama during the fourth day of wedding festivities, other events in the same day give further credence to the idea that this section of the Hochzeit was a source for the opera. In the morning of that day, the Hochzeit’s narrator, Christian Rosenkreuz, goes with the other guests to the main hall of the palace where everyone was given new clothing and a “weighty medal of gold, whereupon were figured the sun and moon in opposition,” and on the reverse side a poem: “The light of the moon shall be as the light of the sun, and the light of the sun shall be seven times brighter than at present.” The sun and moon, Masonic symbols, have been consistently recognized as elements in The Magic Flute, and they are the “greater and lesser lights” of 4th day. The sun is associated with Sarastro’s realm, through allusions to the day or by direct use of the term: waiting for the sunrise (II, xx, and vi) and Sarastro’s appearance first at high noon and finally at daybreak (I, xiv; II, xxx); Sarastro wears the seven-fold sun-circle on his chest. The Queen of Night is associated with nocturnal stars and the moon, the “lesser lights” which illumine the night. Monostatos, attempting to steal a kiss from the sleeping Pamina, addresses the Queen indirectly when he sings “Dear, good moon, forgive me. …moon, hide from that. Should it displease you to see, then shut your eyes” (II, viii). As ruler of the night, the Queen has often been depicted in stage illustrations and design riding on a crescent moon (Karl Friedrich Schinkel, 1816, and Simon Quaglio, 1818) or appearing with the moon in attendance (the pocket book Orphea, 1825); her appearance to Pamina in the moonlit garden in Sarastro’s palace (II, viii) is one of the most dramatic moments in the opera as she attempts to force Pamina to undertake Sarastro’s murder and sings of her burning rage against him. The “opposition of sun and moon” in the characters of Sarastro and the Queen not only creates a dialectic polarity but is particularly important because its opposite, the synthesis of the two, in the “conjunction of sun and moon,” is symbolized in the union of Tamino and Pamina, the alchemical royal couple who achieve the alchemical sacred union.

In another event in the morning of the fourth day, Rosenkreuz and the other guests, all “worthy men,” enter a lively discussion of the arts. Rosenkreuz is made aware of the fact that he is much older than the other guests and the women who have been escorting them. One of the women promises that the burden of age will be removed from him if he behaves well toward her. Playful banter begins among the guests and the women concerning how to decide which of the women will be the bed companion of each particular guest that night. Several possible ways to decide the matter are suggested, but in each case the women manage to avoid being paired with the guests, who are all men. Cupid, a messenger from the King and Queen, enters, drinks a health from a golden cup, summons the principal woman to the royal presence, and leaves with her. Those remaining in the room begin to dance.

The parallel in The Magic Flute concerns Papageno and his bantering with the old woman, who is in reality Papagena (II, xiv and xxiv). In the first of these scenes, Papageno’s age—28—is compared with the “old woman’s”—18. Learning that the woman has a boyfriend who is ten years older than she, and disbelieving the woman’s age as 18, Papageno laughs heartily and comments, “That must be some love affair!” He assumes she is describing a “December” love, and is astounded when the woman identifies Papageno himself as her “boyfriend.” In the later scene, Papageno has drunk “splendid” wine and under its effects realizes that his principal desire is for a “girl or a little woman.” The old woman appears again and tells him that in exchange for his fidelity she will love him tenderly. After a brief consideration of the alternatives, Papageno agrees, and the “old woman” is transformed into the 18-year-old Papagena, “clothed just like Papageno.” Before Papageno can embrace Papagena, she is taken away from him by one of the priests, who declares that Papageno is not yet worthy of her. The transformation in age, the requirement that the male “is good to” or “behaves well toward” or is “faithful to” the woman, the teasing discussion of sexual pairing, the role of the “drink of wine” in conjunction with increasing recognition of sexual desire—the term cupidity is appropriate here—and the deprivation of woman’s company are all common to both the Hochzeit and the opera. However, in this case, as with aspects we have seen earlier, the opera includes the material in reorganized format and reverses the roles of the characters who are to undergo the transformation in age.

Further illumination on Papagena’s transformation from old age to youth is available through a reading of the Elucidarius, the commentary on the Chymische Hochzeit, in its discussion of the Fourth Day. The author writes:

|

…in this place in the Chymische Hochzeit, it will be further shown quite important that an artist should not be discouraged and, so far as he hopes for other things, must free the royal maiden [Tamino’s role!], which is his work to bring to perfection: These are the words:

|

|

In my youth I loved an honorable maiden; my love can achieve its desired goal by these means, that I used a little old matron (coagulated earth), she indeed finally brought me to her, and I even had to swear an oath to have each as my wedded wife for a year, etc.

|

The oath of “fidelity” for a year’s marriage to both an old woman and a maiden is the key to the lover’s success in finally winning his “honorable maiden.” In the Hochzeit, the lover’s problem originally was to decide which woman to accept first, the young or the old. In the opera, an answer is provided: the old is the young. Papageno, longing for a mate who looks just like him, is guided by the old woman Papagena to swear fidelity to her in her aged form; once the oath is given, Papagena assumes her young form, that of a maiden, who must nevertheless yet be freed from the priests’ confinement through Papageno’s “becoming worthy.”

In the evening of the fourth day, Rosenkreuz describes another event which is startling in that it has not only to do with alchemical symbols but seems to employ specifically New Testament symbolism as well. In this event, Rosenkreuz watches from his window at midnight while the bodies of seven men, whose heads had earlier been cut off and placed into a black sack, are transferred to seven ships which sail into the harbor. Each of the ships is alive with lights and each is attended by a flame which hovers above it. When the bodies have been put on board the ships, the lights on the ships are extinguished; as the ships sail away, only the flame is visible above them. Rosenkreuz interprets the flame to be the spirit of the beheaded men. Associated with the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost in the form of a tongue of fire which hovered over the heads of the Apostles (Acts 2:3), the flame suggests the description of the Two Armored Men in the opera scene just prior to Tamino and Pamina’s entrance to the trials of fire and water (II, xxviii). These men are dressed in “black armor…on their helmets is a flame. They read [to Tamino] the transparent script which is inscribed on a pyramid…” The black armor echoes not only the midnight setting of Christian Rosenkreuz’s experience but also the decaying state of the decapitated bodies over whose ships the flame burns; the living-spirit symbol atop the negated body, blackened in decay, seems clearly an allusion to the alchemical process of nigredo. It is further possible to interpret the Armored Men’s reading of the “transparent script” as a kind of “speaking in tongues,” the other miraculous characteristic of the enspirited Apostles at Pentecost. This pair of symbols in the opera—the flame above the head and the mysterious reading—is entirely consistent with the concept of spiritual regeneration which we have identified in the overall structure of the opera and the broader alchemical references in both the opera and the Rosicrucian literature. (We should note here that the “text” of the Armored Men virtually duplicated the inscription over the entrance to the trials through which Sethos, the Egyptian prince in Terrasson’s novel, had to pass in his preparation for priesthood.)

Both the Elucidarius and the Chymische Hochzeit have provided substantial points of commonality with the plot of the Magic Flute, as the preceding comparisons have shown. One other work from the early Rosicrucian corpus is also important as a factor in the plot and text of the opera: this is Johann Valentin Andreae’s Christianopolis of 1624. Frances Yates suggests that Andreae had been strongly influenced in the writings of Christianopolis by another utopian work, City of the Sun, of ca. 1602, by Tommaso Campanella. An ex-Dominican revolutionary under the influence of the mystic reformer Giordano Bruna, Campanella wrote his fantastic description of the ideal society while in prison in Naples; among his visitors there were friends of Andreae, through whom a Latin version of City of the Sun was transmitted to and published in Frankfurt in 1623. [RE, 138.] Andreae’s city, its inhabitants, culture, raison d’être, governance and even physical structure, while parallel to Campanella’s Sun City in many ways, shows striking details which invite comparison to aspects of The Magic Flute’s plot, text and scene design.

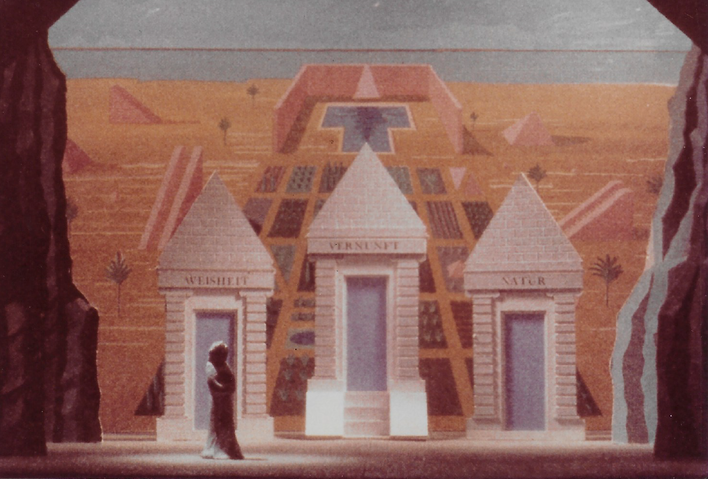

Of the two realms depicted in The Magic Flute, that of The Queen of Night and that of Sarastro, Sarastro’s is the mirror of Andreae’s Christianopolis. Sarastro’s palace, for example, is described even by the Three Ladies in the service of the Queen of Night—“hostile witnesses” as it were—as “splendid and very carefully watched,” and situated in “a pleasant and charming valley” (I, v). Tamino himself, upon approaching the three-temple complex in the palace grounds, exclaims, “Is this the seat of the gods? The gates, the columns show that knowledge and labor and artistry dwell here” (I, xv). Just so, Andreae’s pilgrim, having been shipwrecked and brought by an inhabitant of the city to its gates, writes: “Meantime the sight and the beauty of the city as we approached it surprised me greatly, for all the rest of the world does not hold anything like it or to be compared with it. So turning to my guide I said: ‘What happiness has established her abode here?’ And he answered: ‘…[Religion] built a city which we call Christianopolis, and desired that it should be the home, or, if you prefer, the stronghold of honesty and excellence…”’

We learn indirectly that Sarastro’s domain is in part beautified and enlivened by a series of waterways when slaves in the palace describe in spoken dialogue Pamina’s attempt to escape: “the girl was smarter that I thought. In the very moment when he thought he had won, she called Sarastro’s name. This shook the Moor; he stood mute and motionless; at this instant Pamina ran to the canal and rowed in a gondola to the palm grove: (I, ix). Christianopolis, too, has water in abundance, some supplied naturally, some artificially; it is also surrounded by a moat stocked with fish.

Triangular shapes are frequently described in The Magic Flute. Pyramid-shaped lanterns are carried by priests who convene to encourage Tamino in the trials (II, xx); pyramids are provided to each of the 18 priests who confer with Sarastro about Tamino’s and Papageno’s candidacy for the trials (II, i); ruins of pyramids lie in the vestibule to the temple at which Tamino and Papageno enter their first trial (II, ii); and the vaults of pyramids are the location for the priests’ convention of trials of fire and water, two Armored Men read to him a transparent script from a pyramid located between two caves. Even the three temples—Nature, Reason, and Wisdom—which Tamino approaches upon his entry into Sarastro’s realm are connected in a quasi-triangle by means of columns (I, xv). Echoes of the triangle abound: Three Ladies, Three Boys, threefold harmonies, three discretionary words by which the Boys advise Tamino to behave in his trials, three flats in the key signature of the Eb tonic, and so on. Certainly triangles and pyramids have been regarded as attributes of Egyptian landscape and decorative treatment, and we shall examine this ancient source of the symbols in some detail later. However, in Christianopolis as well, the triangle is one of the overall symbols, for the location of the utopian city is on an island located “in the Antarctic zone, 10 of the south pole, 20 of the equinoctial circle, and about 12 under the point of the bull… The form is that of a triangle, whose perimeter is about 30 miles.” Within the triangle, the outer perimeter of the city is a square which is reiterated by smaller and smaller squares of city layout, and in the very center a circular structure, a tower, 100 feet in diameter. Dwellings are three stories high, a total of 33 feet, and the “walks [between them] are arched and supported by columns five feet wide and 12 feet high.”

Much of Tamino’s experience in regard to Sarastro’s realm has comparable material in Christianopolis. Just before his approach to the three temples, Three Boys who are his guides warn him to be “firm, patient, and silent” (I, xv). The narrator of his visit in Christianopolis recount s that his guide advised him, ‘…if you desire to traverse the city (but you must do it with dispassionate eyes, guarded tongue, and decent behavior) the opportunity will not be denied you…” In another instance, Tamino is met at the door of the Temple of Wisdom by an old priest, who questions him closely about his motives and the source of his information about Sarastro; learning that Tamino has been misled by the Queen of Night and her Ladies, he tells Tamino that he will understand the truth only when he becomes one of Sarastro’s company. In Christianopolis, the traveller is interviewed and questioned on moral issues three times. First, he is met at the eastern gate by a guard who asks what the stranger wants, and advises him to not be “one of those whom the citizens of the community would not tolerate among them but would send back to the place from which they had come;” to which advice the traveller reports that “I purged myself by a testimony of my inmost conscience.” The second interview appears to have been concerning the traveller’s “innermost and most private thoughts;” in a statement quite similar to that of Tamino’s guide through the second-act trials, the examiner comments, “My friend, you have undoubtedly come here under the leadership of God that you might learn whether it is always necessary to do evil and to live according to the custom of barbarians… And if God indeed rule you, so that you be free from the attractions of the flesh, then we do not doubt that you are already ours, and that you will be forever.”’ The traveller’s third examination seems to be a continuation of Tamino’s guide’s comments and also reflects some of Papageno’s guide’s speech in II, iii, in his inquiry after “to what extent I had learned to control myself and to be of service to my brother; to fight off the world, to be in harmony with death, to follow the Spirit…” This third examiner’s final comment, “’It remains that we pray God that He inscribe upon your heart with His holy stylus the things which will seem, in His wisdom and goodness, salutary to you…”’ has echoes in Sarastro’s command to the Speaker, “And you, friend, whom the gods through us designated as upholder of truth, fulfill your holy office, and through your wisdom teach both of them what the duty of humanity is, and teach them to now the power of the gods!” and the opening of his prayer to Isis and Osiris, “Oh, Isis and Osiris, grant the spirit of wisdom to the two who are new: (II, i). Finally, at the conclusion of the third examination, the examiner gives the traveller “three men…worthy individuals as evident from their countenances; and they were to show me around everywhere.” In The Magic Flute, Three Boys are Tamino’s guides to the entrance to Sarastro’s realm and participate in seeing him through the trials. While the Three Boys have been seen as derived from one of the Dschinnistan tales [Introduction to the English National Opera Guide series, Nicholas John, ed., London: John Calder, 1980, p. 14.], there is evidence here to suggest another, and earlier, source for this detail in the opera.

The administration of Christianopolis is given to 24 councilors and eight men who supervise eight other men in their care of districts of “towers” within the city While there is no specific process stipulated by which these officials are chosen, it is clear that the character of the individuals is of great importance in their being appointed: “In this republic no value is set on either succession of title or blood apart from virtue. For while it is true that those who deserve well are given the highest rank and are decked with medals, yet the advantage of this to their children as in advance of others, is that they are admonished more frequently of this family example, and thus the heredity of virtue is inculcated.” The citizens have a part in choosing the councilors in a common meeting. They also meet together “as often as the ordinances require” to decide both sacred and civil matters. Sarastro’s realm is governed in a similar manner, with a few initiates being responsible for specific functions especially in regard to administering the initiatory trials for Tamino and Papageno; the eighteen priest-initiates form a council to decide Tamino’s worthiness to attempt the trials; and the entire citizenry meets to witness the dispensation of justice at the end of Act I and the victory of the “good” at the end of the opera.

Both Christianopolis and Sarastro’s realm place great importance on the education of the people. Not only is the education of youth described in great detail in Christianopolis, but the entire work has a strong didactic thread running throughout. Similarly, The Magic Flute is principally a didactic opera in which the young royal couple are taken successively through experiential training sessions calculated to increase their moral and physical strength for the task of ruling a people. In Christianopolis, male and female children are educated separately to read and write as well as to do the life-tasks they will have as adults; in Sarastro’s realm both Tamino and Pamina are trained for governing, by quite different tactics, and in two different types of trials, until they are “worthy” to be unified in fire and water together.

A final point of great importance links Christianopolis and The Magic Flute in quite a subtle but real way, Christianopolisis predicated on the grievous tribulation of the true Church of Christ under the oppression wreaked by Antichrist; its purpose is to provide a hope-filled description of a society governed by spiritually enlightened men in whom the simplicity and virtue of the earliest Christians are embodied. Because the entire population of Christianopolis strives after this same way of life and thought, there is generally none of the vice and corruption and dissention that plagues the rest of the world. There are explicit references to Martin Luther’s works or ideas as paradigms for the city’s culture. In Sarastro’s realm, of course, there is a similar striving after wisdom, justice, and brotherly love. Sarastro’s aria “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” elaborates on just this theme.

Mozart's "In diesen heil'gen Hallen" (Sarastro, Die Zauberflöte), Gautier Joubert, bass | J. Journaux, piano

More pointed—if also more disguised—is the direct reference to the state of the “outside” world conveyed in Mozart’s choice of a chorale tune which belongs to a text by Luther himself: “Ach Gott vom Himmel sieh’ darein.” The chorale text, a paraphrase of Psalm 12, is concerned with the tribulation and oppression of the Saints by the Godless who speak and act in falsehood and evil; and God’s intention to aid and preserve his faithful, yet strengthening them and purifying them through this fire of tribulation, as silver is purified in the refiner’s fire seven times over. The melody of the chorale appears in the opera at the point where two Armored Men escort Tamino to the entrance to the trial caves of fire and water; the text of the chorale is not used, but rather a substitute for it is given: “He who travels this road full of hardship becomes pure through fire, water, air, and earth. If he can overcome the fear of death, he rises heavenward from earth. Enlightened, he will then be able to devote himself completely to the mysteries of Isis and Osiris.” The purifying aspect of the tribulation and the hope of eventual victory and glorification in “heaven” echo Luther’s text, but using the context of the Egyptian mysteries of Isis and Osiris. We now know that the opera’s text for this melody is an almost exact borrowing from Terrasson’s pseudo-biography Sethos. Its reference to Isis and Osiris obscures the Christian associations of Luther’s chorale. Yet to those who know the chorale, the connection would be clear. The multilayered common theme of undergoing tribulation to become worthy of a final glory links the opera with Andreae’s Christianopolis and even more with Luther’s beleaguered believer.

We noted earlier that Andrae’s Christianopolis was modeled on Campanella’s City of the Sun. Was City of the Sun also a source work for The Magic Flute? There is an important element in the Campanella work that is absent—or covert—in the Andreae work, yet which we find familiarly echoed in The Magic Flute. This element is the focus on the Sun, and more critical, the role of the city’s chief priest who was in fact a Sun Priest, named for the Sun by the use of the alchemical sun symbol

in Campanella’s manuscripts. (GB 369.) If the alchemical sun symbol is then divided into seven sections, we have a startling image echoing Campanella’s description of a plan of the Sun City. “The City of the Sun was on a hill in the midst of a vast plain, and was divided into seven circular divisions (giri) called after the seven planets.” And: “In the centre, and on the summit of the hill, there was a vast temple, of marvellous construction. It was perfectly round, and its great dome was supported on huge columns.” The seven circular districts surrounding the central circular temple suggests the structure of Sarastro’s Suncircle, and Sarastro himself the equivalent to the Sun Priest in Campanella’s city. Now, while Christianopolis has at its center a circular tower which serves both as temple and city hall or meeting hall, there is a system of diminishing squares rather than a circular plan for subdivisions of the city in Andreae’s city; further, there is no significant dependence in Christianopolis on planetary associations, whether astronomical/astrological or alchemical. The one clear reference to astrological signs in Christianopolis is the introduction, in which a modern pilgrim is recommended to begin his journey to the city in a “vessel which has the sign of the Cancer for its distinctive mark.” This sets the journey to begin at the onset of Summer, when the sun has achieved its solstice. It is noteworthy that a significant Masonic festival celebrates the feast of St. John (Baptist), June 21 – and that John is the prophet of the coming Messiah. In Christianopolis, references to the Sun have Christian connotations: Christ is the Sun who will dispel the fog and the world’s corruption, deceitfulness, hypocrisy. In The Magic Flute, Christian overlay is entirely excluded as a specific element of the text, but so are planetary references with the exception of the Sun and moon. We have earlier described the association of Sarastro with the Sun in the opera. Of particular importance is the description of Sarastro in the libretto: “…Sarastro rides out on a victory chariot which is drawn by six lions” (I, xviii); and in the words of the Queen of the Night to Pamina: “[Your father] turned over the seven-fold sun-circle to the Initiates [of the Temple of Isis and Osiris – Sarastro’s group], of his own free will; Sarastro wears this mighty sun-circle on his chest.” The astrological constellation Leo, the lion, is the Sun’s planetary sign; the Sun was included in the seven planets in astrological reckoning, along with the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter. The six lions and Sarastro, whom they are drawing, take on the aspect of a sevenfold sun symbol. Sarastro’s ornament, the seven-fold sun-circle, is thus a reduplication of the Sun symbol of perfect enlightenment, the opera’s one sign of the macrocosm, the harmony and perfection of which Sarastro’s realm was to emulate in the opera.

Judith Eckelmeyer © 1991

Choose Your Direction

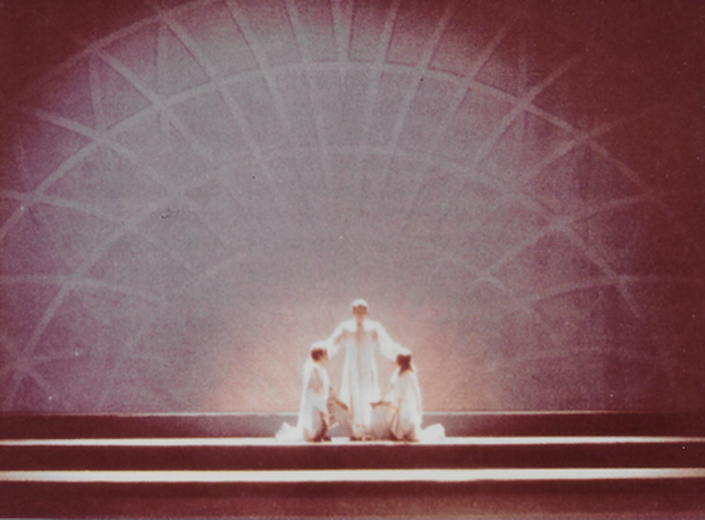

The Magic Flute, II,28.