- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

Béla Bartók - A Biography

If one were to list a half-dozen of this century's most unique and influential composers, Béla Bartók's name would certainly be among those included. Bartók's music contains an organic structural cohesiveness in some way akin to but quite distinct from the dodecaphonic serialism of Schoenberg and his successors; at the same time his music shows enormous rhythmic and harmonic vitality, the result of his lifelong conscious integration of characteristic folk elements, which he himself identified during years of research in remote districts of Eastern Europe and North Africa. Neither associated with a particular "school" of compositional style nor the "father" of a stylistic trend himself, Bartók nonetheless remains in our time a significant figure whose music contains its own kind of remarkable, strong beauty.

Born on March 25, 1881, in Nagyszentmiklós in the Torontál district of Hungary (now a part of Romania), Bartók very early displayed musical gifts. As a child having overcome a number of serious illnesses, he began his formal education and his musical training, principally studying piano with his mother. Shorly thereafter, his father died and Bartók's mother supported the family by teaching piano students. At the age of eleven Bartók presented a piano recital in which he performed one of his own dance pieces. Soon after this concert, the family moved to the active cultural city, Pozsony (now Bratislava), where Bartók completed his schooling and studied piano and harmony with pianist and conductor László Erkel. In Pozsony and later at the Academy of Music in Budapest, Bartók's keyboard skill was considered remarkable; and in spite of his acquaintance with the music of Beethoven, Brahms, and Wagner, Liszt's dazzling virtuosic piano works and great technical display in performances interested him as an artist. Assiduously studying and examining the scores of the standard composers seemed not to trigger any successful compositional effort for him at this time: his muse seemed to have abandoned him.

Two concurrent events turned Bartók's early compositional life around. The easiest to document is his reaction to the first performance in Budapest of Richard Strauss' Thus Spake Zarathustra in 1902. Accordint to Bartók's 1921 autobiographical account of the event, translated by Eva Hajnol-Konyi in Béla Bartók: A Memorial Review (Boosey and Hawkes, New York, 1950), Strauss' music aroused him " as by a lightning stroke," showing him "a way of composing which seemed to hold the seeds of a new life." A year later he completed Kossuth, a symphonic poem modeled after Strauss' A Hero's Life.

Richard Strauss' Also spracht Zarathustra

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra | Mariss Jansons, conductor

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra | Mariss Jansons, conductor

Bartók's Kossuth

BFO/FISCHER

BFO/FISCHER

Strauss' Ein Heldenleben - A Hero's Life, Op.40 (1898)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra | Manfred Honeck

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra | Manfred Honeck

The second impact on Bartók's composing at about the same time was the re-emergence of nationalism in Hungary. Looking back on this era in his life, Bartók wrote in his autobiographical note: "In my studies of folk-music I discovered that what we had known as Hungarian folk songs till then were more or less trivial songs by popular composers and did not contain much that was valuable. I felt an urge to go deeper into this question and set out in 1905 to collect and study Hungarian peasant music unknown until then. It was my great good luck to find a helpmate for this work in Zoltán Kodály, who, owning to his deep insight and sound judgement in all spheres of music, could give me many a hint and much advice that proved of immense value. I started these investigations on entirely musical grounds and pursued them in areas which linguistically were purely Hungarian. Later on I became fascinated by the scientific implications of my musical material and extended my work over territories which were linguistically Slovakian and Roumanian."

Bartók's subsequent systematic treatment of the authentic Magyar peasant music distinguished him from his nationalistic predecessors, Ferenc Liszt and Ferenc Erkel (László's father), whose "Hungarian" style reflected a westernized "verbunkos" gypsy music. In field research with Kodály, Bartók devised a means of collecting, transcribing, and codifying the peasants' songs and instrumental music, recording their performances on an Edison phonograph and wax cylinders. But Bartók, unlike Kodály, explored far beyond the Magyar region, eventually expanding his ethnomusicological studies to include the folk styles of the Arabs of North Africa and nomadic tribes of Turkey in his attempt to determine the cultural relationships between peoples whose music contained similar melodic, structural, and textual characteristics. The scientific thoroughness of his research and the precision with which he analyzed and presented his findings established a precedent for later ethnomusicologists.

The importance of the folk studies can hardly be understated with regard to Bartók's musical development. they provident so much a body of usable source material to be transplanted into his own compositions as they did a data bank for re-evaluating the structural elements of his musical language. In his autobiographical note he wrote: "The outcome of these studies was of decisive influence upon my work, because it freed me from the tyrannical rule of the major and minor keys. The greater part of the collected treasure, and the more valuable part, was in old ecclesiastical or old Greek modes, or based on more primitive (pentatonic) scales, and the melodies were full of most free and varied rhythmic phrases and changes of tempi, played both rubato and giusto. It became clear to me that the old modes, which had been forgotten in our music, had lost nothing of their vigor. Their new employment made new rhythmic combinations possible. This new way of using the diatonic scale brought freedom from the rigid use of major and minor keys, and eventually led to a new conception of the chromatic scale, every tone of which came to be considered of equal value and could be used freely and independently."

Bartók applied these insights only gradually to his compositions; the earliest mature works (from approximately 1903 to 1906) are principally under the influence of Beethoven, Liszt, Strauss, and Brahsm; and outside of the Twenty Hungarian Folksongs of 1906, in which he collaborated with Kodály, very little of the new folk elements appear in his formal works of this time.

By 1905 Bartók was a formidable pianist as well as an aspiring composer. He entered the Prix Rubinstein competition in Paris in both categories, but a cautious committee withheld the composition prize and awarded the piano prize to Wilhelm Backhaus. In 1907, however, he was appointed to head the piano faculty at the Academy of Music in Budapest, a position he retained for nearly thirty years. In the same year, through Kodály's influence, he began studying Debussy's music, seeing in the pentatonic devices a stylistic link with Eastern European peasant music.

From this time onward, Bartók's professional maturation was evident in the First String Quartet (1908), the Allegro Barbaro (1911), Bluebeard's Castle (1911), and numerous works for piano. However, there was very little programming or public acceptance of his works, except through the determinded efforts of Ferrucio Busoni in Berlin and the Waldbauer-Kerpely Quartet, who performed his First String Quartet in major cities in Hungary and throughout Western Europe.

Bartók's String Quartet No. 1

Hungarian String Quartet

Hungarian String Quartet

Bartók's Allegro Barbaro

Zoltan Kocsis, piano

Zoltan Kocsis, piano

The outbreak of World War I, coming right on the heels of Bartók's 1913 research trip to North Africa, prohibited the composer's travel beyond Hungary. In this critically restricted time he produced a ballet, The Wooden Prince (1916), the Suite for piano, Op. 14 (1916), and the Second String Quartet (1917). After the war, famine, political upheaval in Hungary, and Bartók's own illness became significant impediments to composition, yet he was able to complete one of his principal works, The Miraculous Mandarin, in 1919.

Bartók's The Wooden Prince

Chicago Symphony Orchestra | Pierre Boulez, conductor

Chicago Symphony Orchestra | Pierre Boulez, conductor

Bartók's Suite for Piano, Op. 14

Béla Bartók, piano

Béla Bartók, piano

Bartók's Second String Quartet

The Juilliard String Quartet (Robert Mann - Isidore Cohen - Raphael Hillyer - Claus Adam)

The Juilliard String Quartet (Robert Mann - Isidore Cohen - Raphael Hillyer - Claus Adam)

Bartók's The Miraculous Mandarin

BBC Symphony Orchestra | Edward Gardner, conductor

BBC Symphony Orchestra | Edward Gardner, conductor

A two-year cessation of composition followed the completion of The Miraculous Mandarin: Bartók, having applied for a leave of absence from the Academy of Music because of his ill health, decided to remain there after all, but evidently used the time to reassess his goals. In 1921 he entered a decade of active concert and compositional life, bringing out in the twenties a long list of new music and research articles, performing widely, and seeing his composition presented throughout Europe. By now his style had taken on severely dissonant and atonal characteristics arising from his construction of contrapuntal ideas formed from non-traditional scales, his use of intense "motor" rhythms with violent, irregular accents, and his increasing interest in effective exotic sonorities. Structural tightness predominated his work; mathematical relationships in theme structures as well as canonic and fugal techniques reflected Bach's influence. He frequently contributed to programs of the new International Society for Contemporary Music,and found in that organization a stimulus for a number of compositions; but the unyielding hardness of sound and the severe architectonic construct in his music won little acclaim for Bartók among the general public. His works of this time (the First Piano Concerto of 1926, three piano sonatas, the Third and Fourth String Quartets of 1927 and 1928) were seen as assaults on the still commonly held stereotypes of "simple" folk music. Even during his visit to the United States in 1927, to enter his Third String Quartet in a contest sponsored by the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia, the focus of his public appearances was on his piano performances, while critics' opinions of his compositions remained conservatively unreceptive.

Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 1

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen

Yuja Wang, piano

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen

Yuja Wang, piano

Bartók's Third String Quartet

Juilliard String Quartet

Areta Zhulla, violin | Ronald Copes, violin | Roger Tapping, viola | Astrid Schween, cello

Juilliard String Quartet

Areta Zhulla, violin | Ronald Copes, violin | Roger Tapping, viola | Astrid Schween, cello

Bartók's Fourth String Quartet

Quatuor Ebène

Pierre Colombet, violin I | Gabriel Le Magadure, violin II | Mathieu Herzog, viola | Raphaël Merlin, cello

Quatuor Ebène

Pierre Colombet, violin I | Gabriel Le Magadure, violin II | Mathieu Herzog, viola | Raphaël Merlin, cello

By 1930, having returned to Budapest, Bartók began to see more favorable public reaction to his music. For a few years the compositions again flowed (Twenty Hungarian Folksongs, 1929; Cantata Profana, 1930; the Second Piano Concerto of 1930; the Fifth String Quartet, 1934; and Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, 1936) and his publications on folk music continued. Joining the Hungarian Academy of Science in 1934, he left his teaching position at the Academy of Music and intensified his systematic investigation of comparative folk sources. In 1937 he traveled to Turkey in what would be his last research trip on behalf of these studies.

Bartók's Twenty Hungarian Folksongs

Lantos István, Sziklay Erika

Lantos István, Sziklay Erika

Bartók's Cantata Profana

Orchester des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens Chor des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens

György Lehel, conductor

Jósef Réti, tenor | András Faragó, bass

Orchester des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens Chor des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens

György Lehel, conductor

Jósef Réti, tenor | András Faragó, bass

Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 2

Orchestra of the Academy of Santa Cecilia, Rome

Antonio Pappano, conductor

Yuja Wang, piano

Orchestra of the Academy of Santa Cecilia, Rome

Antonio Pappano, conductor

Yuja Wang, piano

Bartók's String Quartet No. 5

Juilliard String Quartet

Juilliard String Quartet

Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France conducted by Alan Gilbert

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France conducted by Alan Gilbert

By 1939, Nazi influence and control had spread throughout Germany and Austria and threatened to overcome Hungary. Bartók found himself in the position of abhorring the German imposition on Hungary and resenting acquiescence to it among his countrymen. When Germany invaded Austria, he sought protection for his manuscript scores, which he realized would probably be destroyed if Hungary were invaded. He sent some manuscripts to friends in Switzerland; he turned over the rights to others in preparation and to all future works to Ralph Hawkes, publisher for Boosey and Hawkes of London. After a brief concert tour in England in 1939, Bartók retired to Switzerland and began work on the Sixth String Quartet. His mother's death brought him back to Budapest, where he completed the quartet. The following year he embarked on a tour to America, seeking opportunities to enter the country on a more permanent basis. Returning briefly to Hungary in the summer of 1940, he reentered the United States with his wife, Ditta, intending to remain until the war was over, if not permanently.

Bartók's Sixth String Quartet

The Juilliard String Quartet (Robert Mann - Isidore Cohen - Raphael Hillyer - Claus Adam)

The Juilliard String Quartet (Robert Mann - Isidore Cohen - Raphael Hillyer - Claus Adam)

Bartók's immediate acceptance by supporters and friends gave him access to performing opportunities, academic honors, and concert tours (one of which brought him to Cleveland). Eventually a position was created for him at Columbia University, where he began a study of Yugoslavian folk music collected on records by Harvard professor Milman Parry. The Columbia appointment was periodically jeopardized by its temporary status and lack of financial support; and in spite of the patchwork engagements largely instigated by Hungarian musicians such as Fritz Reiner, Joseph Szigeti, and Eugene Ormandy, through the Koussevitsky Foundation and Bartók's nomination to ASCAP, Bartók's music was still hard to "sell" to the critics and the public. The Bartóks lived in a small New York City apartment on the brink of financial disaster. In 1942 Bartók's younger son Peter joined them in New York, the one member of the family to do so; Bartók's elder son Béla, his sister Elza, and their families remained out of communication in Hungary.

Despite the distress of insecure income, worry about the well-being of family and friends, and his own increasingly poor health, Bartók continued to compose. He completed his Sonata for Solo Violin and the Concerto for Orchestra in 1944, and saw them enthusiastically received by audiences at their first performances. He was given several commissions for new music, and with his son's assistance began work on the Viola Concerto. He never completed this concerto. His health, which had been especially fragile since the beginning of 1943, finally broke. After only a few days in the hospital, he died of leukemia on September 26, 1945.

Bartók's Sonata for Solo Violin

Yehudi Menuhin, violin

Yehudi Menuhin, violin

Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky

Judith Eckelmeyer © 1981

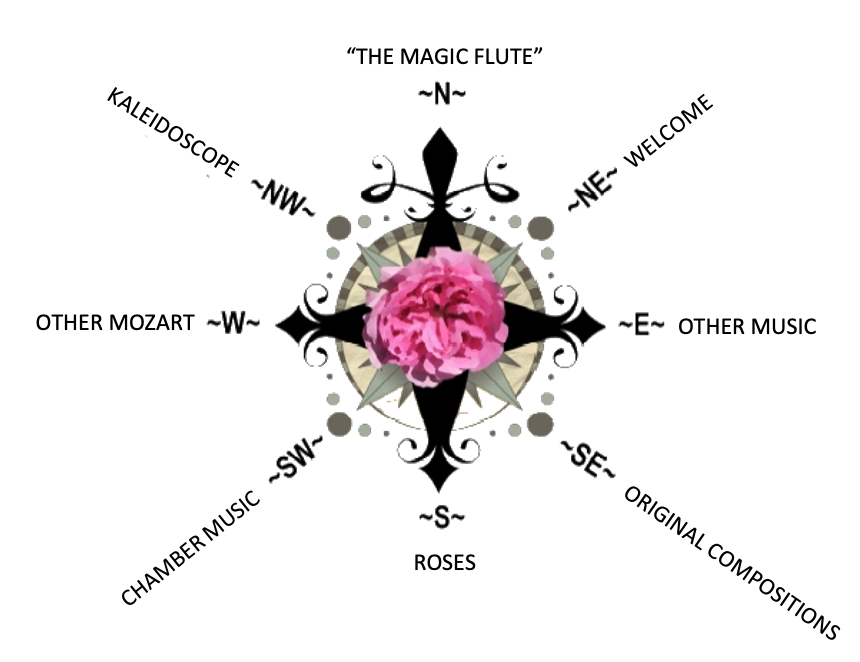

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.