- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

MOZART'S REQUIEM

Notes on Mozart's Requiem, K. 626

by Judith Eckelmeyer and Students

WHAT IS A REQUIEM MASS?

A Requiem Mass is a variant on the primary worship service of the Roman Catholic church, the celebration of the Lord's Supper called the Mass. It is a Mass for the “Faithful Departed”, celebrated either as a funeral or as a memorial service. The word "requiem" is derived from the Introit, the first liturgical action in the service when the participants enter the church; the first words in Latin are “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine" (literally, Rest eternal grant them, Lord).

The specific form of the Requiem Mass developed over the early centuries of the Christian era but was essentially settled by the fourteenth century. Thomas of Celano's (d. 1256) long poem beginning with the words Dies irae (day of wrath), describing the terror of Judgment Day and pleading for mercy, became an integral part of the Requiem in the mid-sixteenth century; it is one of the five Sequence texts still used in the Roman Catholic liturgy.

Many composers have written settings of the Requiem using the original Latin words set to new musical settings in place of the traditional Gregorian chants. The movements of musical settings generally correspond to the major musical parts of the liturgical service: Introit, Kyrie, Gradual, Tract, Sequence (Dies irae), Offertory, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and Communion. However, composers have not always composed settings for all of these parts.

Many composers have written settings of the Requiem using the original Latin words set to new musical settings in place of the traditional Gregorian chants. The movements of musical settings generally correspond to the major musical parts of the liturgical service: Introit, Kyrie, Gradual, Tract, Sequence (Dies irae), Offertory, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, and Communion. However, composers have not always composed settings for all of these parts.

Notable Requiem settings range from Johannes Ockeghem's in the fifteenth century to Benjamin Britten's in the twentieth. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's setting of the Requiem dates from 1791. In his setting, the Introit and Kyrie are combined to form the initial movement. The vivid Dies irae is then given an extended treatment in several movements (Dies irae, Tuba mirum, Recordare, Confutatis, Lacrymosa), followed by the Offertory in two movements (Domine Jesu Christe, Hostias) and the Sanctus in two movements (Sanctus-Osanna, Benedictus-Osanna). The setting concludes with the Agnus Dei and Communion (Lux aeterna) in one movement.

MOZART AND THE REQUIEM

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) undertook the setting of the Requiem, he had been living and working in Vienna for some ten years as a freelance composer and teacher, having left his family home in Salzburg and his employment there with Archbishop Colloredo. His fortunes had risen steadily during the first five years in Vienna: he and his wife Constanze had begun their family; he had grown musically through the study of Sebastian Bach's contrapuntal style and exploration of single-reed sonorities; and he had entered Freemasonry, and had become immersed in the activities of at least two of the nine lodges of Freemasons in Vienna. His operas were performed at court in Vienna and in her sister city, Prague. He had well-placed private piano and composition pupils. Concerts at which his works were presented--especially his own performance of his piano concertos--were well subscribed.

From about 1787, however, circumstances for Vienna and for Mozart altered considerably. War with the Turkish Empire drained Austria's material and financial resources, forcing aristocratic families into desperate reductions in lifestyle and even the sacrifice of family members in the army. While Mozart found it increasingly difficult to find subscribers for his public concerts and was offered very few commissions for large works, he was not without paid commissions, as romanticized biographies would have it. In fact, although he never was granted the principal post at court, from 1787 he was Kammermusicus at the court and as such was given the duty to write dance music for the Carnival seasons (he is believed to have scrawled "too much [money] for what I do, too little for what I could do!" over a receipt for his payment from the court).

From about 1787, however, circumstances for Vienna and for Mozart altered considerably. War with the Turkish Empire drained Austria's material and financial resources, forcing aristocratic families into desperate reductions in lifestyle and even the sacrifice of family members in the army. While Mozart found it increasingly difficult to find subscribers for his public concerts and was offered very few commissions for large works, he was not without paid commissions, as romanticized biographies would have it. In fact, although he never was granted the principal post at court, from 1787 he was Kammermusicus at the court and as such was given the duty to write dance music for the Carnival seasons (he is believed to have scrawled "too much [money] for what I do, too little for what I could do!" over a receipt for his payment from the court).

From 1789 his patron Baron Gottfried van Swieten commissioned him to reorchestrate several Handel oratorios for performance at his private academies of "ancient" music. The commission to compose La clemenza di Tito for the 1791 coronation celebration of the new Austrian Emperor, Leopold II, in Prague, virtually concurrent with his completing The Magic Flute, further buffered Mozart's circumstances. Also in that year, Mozart thought to put himself in a favorable position for appointment as the next Kapellmeister of St. Stephen's Cathedral by offering his unpaid services to the ailing and aging Kapellmeister Hoffmann; there is every likelihood that he would indeed have succeeded Hoffmann. This new career plan appears to have resulted in his composition of a large Kyrie in D minor (previously thought to have been written about 1780), probably the opening movement of a complete mass setting.

Mozart received the commission to compose a Requiem during the summer of 1791. The commission came from Count Franz von Walsegg zu Stuppach (1763-1827), whose wife had died in February, and who had determined to honor her memory with a sculpted monument and a Requiem mass which would be performed annually for her soul. Walsegg's practice had been to commission works by various composers, reserving the sole rights to the works for himself; he would then copy them in his own hand and perform them under his own name. He employed agents in Vienna to ask Mozart to write a Requiem; Mozart was told neither from whom the commission had come nor the person it was to commemorate.

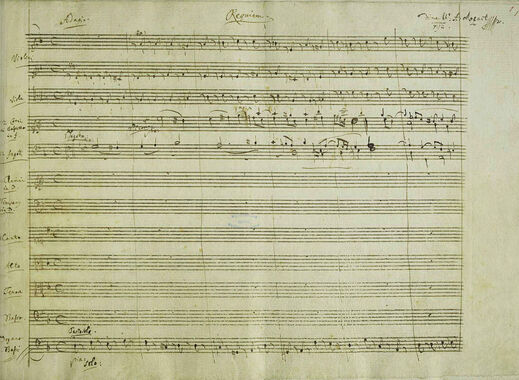

Mozart's untimely death came on December 5, 1791. Recent scholars have suggested various causes, ranging from Schönlein-Henoch Syndrome (an "allergic hypersensitivity vasculitis", according to Peter J. Davies) to a subdural hematoma and treatments related to it--quite other than poison, whether at the hand of disgruntled fellow Masons or by jealous Court Composer Antonio Salieri. There is no historical evidence of any involvement by Salieri in Mozart's death or in the completion of the Requiem, contrary to the story in Amadeus, Peter Shaffer’s popular play and its subsequent film version. At the time of Mozart’s death, the Requiem was not completed, but rather existed in sections of full manuscript, sections of partially completed manuscript, and sketches. Nevertheless, to honor the terms of the commission, Constanze Mozart arranged to have the work completed. A copy of the completed score was delivered to Count Walsegg by early March, 1792; another copy was bought by Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, and Constanze held a third copy. Mozart’s pupil and assistant, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, also probably held a copy.

The earliest performance of the complete Requiem took place on January 2, 1793, at the Imperial court in Vienna, under arrangements made by Gottfried van Swieten for the benefit of Constanze and the two young Mozart children. Count Walsegg first had the work performed December 14 of that year in Wiener Neustadt; his score for the occasion was the one he had copied in his own hand, although he still possessed the original he had received from Constanze. Even earlier than these performances, however, the Introit, entirely completed by Mozart in his own hand, and probably also the Kyrie had been performed at a service for him at St. Michael Church in Vienna on December 10, only a few days after his burial. The first performance of the work elsewhere was in Leipzig in 1796.

In about 1799 the Leipzig publishing company of Breitkopf and Härtel began making plans to publish the Requiem. The score they intended to base their edition on was from a copy made from Constanze's when she was in Leipzig for the 1796 performance of the Requiem. From the publishers' standpoint, the copyist's hand seemed to bring the authenticity of the work into question (there had been rumors about its authenticity before this). Moreover, Constanze was obligated to get permission from Count Walsegg to publish the work because he owned the sole rights.

It is at this point that the names of Mozart's student, Franz Xaver Süssmayr (1766-1803) and his friend the Abbé Maximilian Stadler (1748-1833) must be introduced with respect to the Requiem's completion. To try to clear their path to publishing the work, Breitkopf and Härtel pursued Constanze's suggestion to ask Süssmayr to clarify his role in completing the Requiem. Süssmayr's response explained which portions were Mozart's, and stated that the Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei were "wholly composed by me." Subsequently, Count Walsegg's lawyer met with Abbé Stadler and Constanze's new husband, Georg Nicolaus Nissen. Stadler circled the portions in Walsegg's score that were not Mozart's; it was clear that he was entirely familiar with the details of the work, even though the handwriting of the sections he circled was almost indistinguishable from Mozart's. His markings of M for Mozart and S for Süssmayr were retained in later editions that distinguish Mozart's from Süssmayr's contributions, and these correspond generally with Süssmayr's description of his own role in completing the Requiem.

Süssmayr's letter to the Leipzig publishers Breitkopf and Härtel along with the fact that extensive portions of the manuscript score are in his handwriting, which was remarkably like Mozart's, led to the conclusion in the early nineteenth century that a significant portion of the Requiem was actually composed by Süssmayr.

Süssmayr's letter to the Leipzig publishers Breitkopf and Härtel along with the fact that extensive portions of the manuscript score are in his handwriting, which was remarkably like Mozart's, led to the conclusion in the early nineteenth century that a significant portion of the Requiem was actually composed by Süssmayr.

WHO WAS FRANZ XAVER SÜSSMAYR?

Süssmayr was born in Schwanenstadt in north-central Austria. In his early years he was educated in singing, violin and organ by his father, Franz Karl, a choirmaster at a local church. At age thirteen he enrolled in the monastery school at Kremsmunster, where he continued his studies in organ, violin and voice, along with a classical education. In 1784 he was admitted to the Ritterakademie to study law and philosophy but found himself continuing his interest in music through the study of composition under Maximilian Piessinger and Georg von Paster. While at Kremsmunster he composed six stage works that were reasonably successful locally. After graduating in 1789 he moved to Vienna and was apprenticed to Mozart in 1790. Mozart gave him the task of composing the recitatives in La clemenza di Tito in the summer of 1791. Mozart often referred to Süssmayr in humorous and sometimes not very complimentary terms in his letters to Constanze.

After Mozart's death, Süssmayr's own compositional and musical career was generally successful, if obscure today. He became harpsichordist and acting Kapellmeister for the National Theater in Vienna in 1792 and overall court theater composer in 1794. He is noted for his singspiel works, the most famous of which is Moses oder der Auszug aus Ägypten (1792); he also wrote ballets, five masses (the Missa Solemnis, published in 1810, has a Sanctus beginning very similarly to that in Mozart's Requiem), two German Requiems, twelve cantatas, a secular canon for three voices, two symphonies, thirty dances and two quintets for chamber orchestra.

EARLY CONTROVERSY OVER THE REQUIEM'S AUTHENTICITY

The matter of the authenticity of Mozart's Requiem came into question again in 1825 when Gottfried Weber, a musical theorist and magazine editor, wrote an article saying that it was Süssmayr, not Mozart, who had written the score that Breitkopf and Härtel had published. At that time, the extant manuscripts of the work were held by private individuals. (The first manuscript to be acquired at the Court Library, where it could be studied publicly, was the autograph score of the Sequence, without the Lacrymosa; Stadler presented it in 1829.)

The lack of documentation made resolution of the authenticity question impossible in Weber's era, even though the question itself was quite valid. Nevertheless, from that time there have been numerous theories about how much of the Requiem was truly Mozart's, and much speculation about how many people besides Süssmayr had a hand in writing it. Some of the methods used in answering these questions have included handwriting analysis of the autograph copy, and searching through letters, diaries, and records for any information regarding the work's completion. On the whole, these early theories cast Süssmayr in a questionable light, implying that he did away with all tangible evidence of any foundation by Mozart for those portions of the Requiem he claimed to have written in order to benefit from Mozart's work.

The authenticity question is still valid today, but in a different way from previous years, because manuscripts for the entire work are now available for study. We now know that two other students of Mozart's, Franz Joseph Freystädtler (1761-1841) and Joseph Eybler (1765-1846), also played a part in the Requiem's completion. Part of the Kyrie is in the hand of Freystädtler, who may have completed the fugue for the performance at Mozart's funeral. In addition, manuscripts have been found showing that Eybler, who had signed an agreement with Constanze to complete the Requiem before the task fell to Süssmayr, appears to have orchestrated five sections of the Sequence. Abbé Stadler (the same who helped the publishers distinguish Süssmayr's work from Mozart's) also appears to have worked on the Offertory movements. Süssmayr subsequently copied and made changes in the work of these men, although it is possible that the four of them were working in collaboration. There is now no doubt that Süssmayr had a major role in completing Mozart's unfinished Requiem, but the nature of that role varies according to different scholars' findings. The specific question before these scholars today is: how much of the work was done by Süssmayr and the others according to Mozart's written or verbal instructions. More recently, musical analysis based on style characteristics of Mozart's compositional techniques has been employed to try to answer the question.

SOME RECENT THEORIES ON THE AUTHENTICITY QUESTION

FRIEDRICH BLUME

One of the many scholars who has argued against the large role Süssmayr was thought to have played in completing the Requiem is Friedrich Blume, whose article "Requiem But No Peace" was first published in 1961. In the article, Blume outlines three main problems with the Requiem: 1. the authorship problem, that is, who wrote what sections of the work; 2. the instrumentation problem; and 3. the dating problem. In an attempt to find solutions Blume examined the letters of the people involved, conclusions drawn by other music historians, and the score of the Requiem itself.

Blume's first conclusion is that Süssmayr was incapable of completing as much of the Requiem as is attributed to him. Blume states, "The assumption operative up to now according to which Süssmayr is to be considered the composer of the missing portions as long as nothing can be proved to the contrary, seems today less justified than the assumption that the independent composition of the closing portions cannot be ascribed to Süssmayr so long as doubts concerning his talent...are not resolved by demonstrating a corresponding accomplishment of his own from his pen." Since we have no proof that Süssmayr was capable of such a composition, we should not attribute it to him. Instead, Blume believes that Süssmayr had more sketches to work from than was previously believed and that he probably destroyed them when he was done.

Blume's first conclusion is that Süssmayr was incapable of completing as much of the Requiem as is attributed to him. Blume states, "The assumption operative up to now according to which Süssmayr is to be considered the composer of the missing portions as long as nothing can be proved to the contrary, seems today less justified than the assumption that the independent composition of the closing portions cannot be ascribed to Süssmayr so long as doubts concerning his talent...are not resolved by demonstrating a corresponding accomplishment of his own from his pen." Since we have no proof that Süssmayr was capable of such a composition, we should not attribute it to him. Instead, Blume believes that Süssmayr had more sketches to work from than was previously believed and that he probably destroyed them when he was done.

As for the instrumentation, Blume doubts that Mozart intended to use the same combination of instruments throughout the work. He contends that in a wholly Mozart work there is a variety of colors and instrument combinations, and that the absence of the woodwinds is very uncharacteristic of Mozart's writing in this period of his life. Blume calls Süssmayr's orchestration "thoughtless and gross" and believes that the pupil did not follow the path that his teacher intended.

Finally, Blume addresses the dating of the work. He believes that work on the Requiem began in early summer before work on The Magic Flute and was finished after, although the movements were not necessarily composed in order. He believed that Mozart had made sketches for portions of all the movements, and that Süssmayr worked from them rather than creating original material from which to complete the work. Not long after Blume completed his article, sketches for portions of the Requiem were found.

Blume admits that we may never find all the answers to these questions, but he believes that the theories that were accepted until the 1960s are erroneous.

Finally, Blume addresses the dating of the work. He believes that work on the Requiem began in early summer before work on The Magic Flute and was finished after, although the movements were not necessarily composed in order. He believed that Mozart had made sketches for portions of all the movements, and that Süssmayr worked from them rather than creating original material from which to complete the work. Not long after Blume completed his article, sketches for portions of the Requiem were found.

Blume admits that we may never find all the answers to these questions, but he believes that the theories that were accepted until the 1960s are erroneous.

FRANZ BEYER

|

Franz Beyer is another scholar critical of Süssmayr's contributions to the Requiem, recognizable by its many inaccurate harmonic realizations and, at times, insensitive scoring in contrast to Mozart's error-free writing. In the preface to his edition of the Requiem, published in 1971/1979 by Kunzelmann, Beyer attempts to clarify the problems verbally. This edition of the score incorporates Beyer's corrections to the part writing according to Mozart's standard practice.

The un-Mozartean passages attributed to Süssmayr to which Beyer points in his preface include consecutive octaves between the first basset horn and the tenors, wrong notes in the trumpets and timpani, and the reduction of the woodwinds to only three parts. Among the orchestration problems, again attributed to Süssmayr, is the use of wrong accidentals in the basset horns (flat and natural signs are used in front of each pitch F, instead of naturals and sharps respectively). Another problem is that the basset horns and bassoons often lie identically with the vocal parts, which forces the basset horns into the upper register. Beyer points out that Mozart customarily used the higher notes of this instrument only in solo and forte passages. Beyer concludes that the controversy over which part of the Requiem is Süssmayr's could have been avoided had Süssmayr signified his role in the completion of the work with greater clarity. |

RICHARD MAUNDER

Richard Maunder, a Fellow at Christ College, Cambridge University, has created one of the most radical solutions to the questions surrounding Mozart's Requiem. In his revision of the work, published about 1988, he has stripped the score of everything which he believes was not Mozart's. This includes the last three movements (Sanctus, Benedictus and the Agnus Dei portion of the last movement), as well as what he believes is Süssmayr's completion of the Lacrymosa. Furthermore, Maunder has reworked much of the orchestration where he believes it to have been done by Süssmayr. He has based his own orchestration on similar passages in The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito, Mozart's last two operas which he may very well have worked on concurrently with the Requiem. Based on a recently discovered sketch by Mozart, Maunder also wrote his own "Amen" fugue to complete the Lacrymosa (this in spite of the possibility that Mozart may have specifically chosen, after writing the sketch, to avoid the formality of a fugue in favor of the simple chordal setting of the Amen present in the traditional version of the Requiem).

CHRISTOPH WOLFF

The most recent solution to the questions around the Requiem is offered by Christoph Wolff, Professor of Music at Harvard University. Wolff has written a book, Mozart's Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies (1994), in which he carefully analyzes source materials (scores, letters, documents) and musical style and concludes that the Requiem is substantially Mozart's work. However, Wolff's scope of consideration extends beyond just Süssmayr's known participation in completing the work; he addresses also the question of how much Mozart had communicated to him and to the others associated with the Requiem's completion concerning his intentions for the work.

Wolff points out that Mozart conceived works in their entirety in his head before writing anything down. The score in his hand was set out in twelve staves as a final version, and in much of the work all the choral writing and the bass lines were complete. The essence of the Requiem, Wolff argues, is contained in the choral writing. The selection of the dark orchestral sounds and passages revealing a new, transparent style of writing indicate that Mozart was embarking on a new compositional phase of his career. Moreover, Mozart, knowing that he was running out of time, had inserted the important orchestral expositions and sketched polyphonic and technically tricky passages. Wolff believes the role of Süssmayr and the others was to fill in the rest according to Mozart's intentions.

Wolff points out that Mozart conceived works in their entirety in his head before writing anything down. The score in his hand was set out in twelve staves as a final version, and in much of the work all the choral writing and the bass lines were complete. The essence of the Requiem, Wolff argues, is contained in the choral writing. The selection of the dark orchestral sounds and passages revealing a new, transparent style of writing indicate that Mozart was embarking on a new compositional phase of his career. Moreover, Mozart, knowing that he was running out of time, had inserted the important orchestral expositions and sketched polyphonic and technically tricky passages. Wolff believes the role of Süssmayr and the others was to fill in the rest according to Mozart's intentions.

In the sections "wholly composed" by Süssmayr, Wolff separates out the choral lines and the brilliant and well-composed passages, and finds a work of Mozartean quality. Thus he argues that Mozart must have communicated his intentions for the whole work to Süssmayr (via sketches, notes, singing and explanation), and that the errors and infelicities at the end are due to Süssmayr's misunderstanding and misremembering and the fact that he was not as skilled a composer as the great master. In the terms of the day, writing out and orchestrating all the parts amounted to "wholly composing" the work, even if all the ideas had come from Mozart. Taking all this into account, Wolff has no doubt that the Requiem as it has survived is substantially Mozart's work, and that those who worked on it were genuinely carrying out Mozart's instructions for completion, and not perpetrating a fraud.

THE ORCHESTRATION OF THE REQUIEM

While the extent of Süssmayr's role in the completion of the Requiem has come under intense scrutiny during the last few decades, the belief that he in some way participated in the project has remained unchallenged. Historians agree that, while Mozart completed the choral parts and left figured bass indications and sketches of some interludes and complex passages, Süssmayr had a hand in completing the orchestral accompaniment, and the peculiarities which occur in the string writing in the work, which are particularly evident after the Lacrymosa, can be attributed to him. The deviations from Mozart's style of string writing are distinguished by rhythmic simplicity and monotony, poor doublings in chords, and lack of a sophisticated melody. In addition, there are times when the strings merely double the chorus rather than having a part of their own. Süssmayr also occasionally wrote an accompaniment where Mozart may have intended chorus alone.

While Süssmayr's hand can be detected in many of the later string parts, Mozart's preferences come through clearly in the early writing for winds. In his scoring for woodwinds, Mozart omitted all of the high, bright sounds: flutes, oboes, clarinets and horns. Instead, two basset horns and two bassoons impart a dark and somber sonority. The basset horn is a member of the clarinet family, but it is lower in pitch (in the key of F rather than B-flat) and has a darker and "reedier" timbre. It was a favorite of Mozart's and appeared in several works, most notably in the Serenade No. 11 known as the "Gran Partita" and in his "Masonic Funeral Music", K. 479a. Unfortunately, this instrument is now nearly obsolete, making the instruments themselves difficult to obtain. Once obtained, the instruments are reputed to be fairly difficult to play. Therefore, the parts originally intended for basset horns are often played by clarinets.

Mozart makes no demand for conspicuous virtuosity in the instrumental writing of the Requiem, unlike that in his Mass in C minor, K. 427. The only exception to this is the unprecedented solo for tenor trombone in the Tuba Mirum, conforming to the text "The wondrous trumpet sounds." The scoring also includes an alto trombone and a bass trombone, reflecting the traditional scoring for three trombones in church music, where the trombone has its origins. The trombones in this Requiem serve to reinforce the choral lines. It is a matter of ongoing controversy, however, how much the trombones should be used and whether Mozart intended to have them as an omnipresent sonority or not. The trumpets and timpani fill out the instrumentation, giving the work the solemn dignity necessary for a Requiem Mass.

Mozart makes no demand for conspicuous virtuosity in the instrumental writing of the Requiem, unlike that in his Mass in C minor, K. 427. The only exception to this is the unprecedented solo for tenor trombone in the Tuba Mirum, conforming to the text "The wondrous trumpet sounds." The scoring also includes an alto trombone and a bass trombone, reflecting the traditional scoring for three trombones in church music, where the trombone has its origins. The trombones in this Requiem serve to reinforce the choral lines. It is a matter of ongoing controversy, however, how much the trombones should be used and whether Mozart intended to have them as an omnipresent sonority or not. The trumpets and timpani fill out the instrumentation, giving the work the solemn dignity necessary for a Requiem Mass.

PERFORMANCE ASPECTS OF THE REQUIEM

While some of the issues about the authorship of Mozart's Requiem will probably never be completely resolved, there are other less controversial problems which can be addressed more easily. One such problem is the pronunciation of the text. The universal pronunciation of the Latin that today's listeners usually hear is a result of the 1903 edict of Pope Pius X, the "Motu proprio", specifying a universal system of Latin pronunciation now referred to as “ecclesiastical” Latin. Prior to this edict, the pronunciation of Latin texts complied with the phonetic rules of each speaker's native language. Therefore, Mozart, in the late eighteenth century, did not hear the modern ecclesiastical Latin that many choirs use today. In fact, what he heard was not even the Latin spoken in Rome, but rather that spoken in Austria, and specifically that spoken in Vienna. The rules governing the usage of vowels and consonants were based on the German language. In Germanic Latin the consonants are much more plosive and pronounced than in ecclesiastical Latin, thus forming a crisper articulation of the music. For example, the pronunciation of the very title of the work, "Requiem", changes the vowel "u" to the consonant "v"; instead of "re kwi em" the second syllable is pronounced "kvi".

Ecclesiastical Latin offers five vowels as opposed to the Germanic Latin, which offers more than twice that number, providing a greater variety of color to the text. For example, the phrase "Kyrie eleison", when pronounced according to the rules of ecclesiastical Latin, uses three vowel sounds. When using a Germanic pronunciation, the same phrase uses five.

Germanic pronunciation also has an impact upon vocal production. Consider the melismatic runs in Mozart's setting of the second syllable of "eleison": in ecclesiastical pronunciation it would sound like the vowel in "let"; in the eighteenth-century Viennese pronunciation this vowel sounds like the "a" in "father." The "a" is a much easier vowel to sing, especially when the vocal line hangs on notes in the upper register within a part, as is often the case for the sopranos.

ON THE AUTHORSHIP OF THESE NOTES

|

These notes were prepared as part of one segment of the Winter 1995 course Great Choral Works (MUS 484/542) at Cleveland State University. All students in the course and the instructor undertook the research and writing for the material presented here. The class members are: Pamela Clements, Kevin Gibaldi, Linda Gilbert, David Hoffman, Paul Kirk, James Mittelstadt, David Saunders, Dawn Schwartz, Dennis Schwartz, Bradley Upham, and Brenda Wepfer. The instructor is Dr. Judith Eckelmeyer.

|

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.