- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

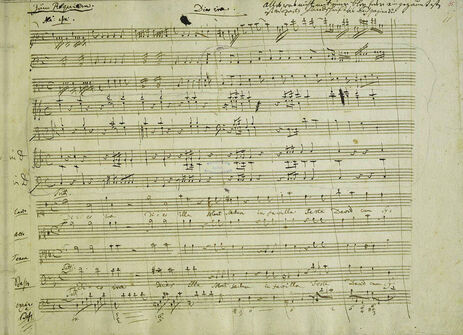

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART: A COMMEMORATION OF THE 235TH ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH; A MEMORIAL IN THE 200TH YEAR SINCE HIS DEATH

by Judith Eckelmeyer

Program notes from Gartner Auditorium Concerts

Cleveland Museum of Art | February 3, 1991

Cleveland Museum of Art | February 3, 1991

In recent years the public has been introduced anew to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The music and particularly the character of the composer are most popularly known as they have been reflected through the devices of Peter Shaffer's Amadeus. The figure of Mozart in this work, memorable and shocking with its mixture of musical brilliance and juvenile scatology, has raised burning questions for many viewers: was Mozart indeed as Shaffer portrayed him? Is more of Mozart's music as delicious as that employed in Shaffer's drama? On the other hand, many of those who knew Mozart's music well before Shaffer's portrayal of the composer have expressed disbelief that the character of Shaffer's creation could have any factual connection with the historical Mozart; in effect, no one who composed such refined, even delicate music could have been so dissolute, so uncouth a person, as Shaffer portrays.

Which is the true Mozart? Is it the obscene, puerile little man, or the incorruptibly pure, Victorian ideal? Both, it turns out, are exaggerations of kernels of reality.

To get acquainted with the man in Mozart's skin, we are best advised to examine the source itself as well as we can some two centuries after the fact. Mozart and his family, often separated by long journeys, were inveterate letter writers. Mozart's own letters to his parents, his most cherished friends, his colleagues, and his fellow Freemasons, contain precious evidence of who he was. The bulk of his extant correspondence, translated by Emily Anderson and published in 1966 by St. Martin's Press, reveals a lively, high-strung, loving, proud, sensitive, sarcastic, generous, playful, insightful, witty, and uncommon individual. Highmindedness and ribaldry are both aspects of his personality, and both affected his musical composition in differing ways.

To get acquainted with the man in Mozart's skin, we are best advised to examine the source itself as well as we can some two centuries after the fact. Mozart and his family, often separated by long journeys, were inveterate letter writers. Mozart's own letters to his parents, his most cherished friends, his colleagues, and his fellow Freemasons, contain precious evidence of who he was. The bulk of his extant correspondence, translated by Emily Anderson and published in 1966 by St. Martin's Press, reveals a lively, high-strung, loving, proud, sensitive, sarcastic, generous, playful, insightful, witty, and uncommon individual. Highmindedness and ribaldry are both aspects of his personality, and both affected his musical composition in differing ways.

The external events of Mozart's all-too-brief life are remarkable, even for today's highly diversified sense of the "norm." As the family's correspondence shows, the child Wolfgang had experiences during his first twelve years that many adults of his day would never have encountered in their entire lifetimes. His later years have the profile of a roller-coaster, with vicissitudes that would demoralize and undo many a modern person, yet in his letters Mozart only very rarely departs from a tone of merely describing his circumstances objectively, recounting, as it were, for the benefit of those who could not be present of the event.

Wolfgang was born in Salzburg on January 27, 1756, to a middle-class musician, Leopold, and his wife, born Anna Maria Pertl. Wolfgang soon demonstrated exceptional response to his father's violin and keyboard playing. By the age of four Leopold was teaching him keyboard technique and the rudiments of music theory; by six, Leopold took Wolfgang and his ten-year-old sister, Maria Anna (Nannerl) on not one but two tours, first to Munich and then to Vienna, to perform as prodigies.

The following year saw the beginning of a long journey, through Germany to Paris and ultimately to London and the Hague. A source of entrepreneurial pride, if not profit, to Leopold, this tour was to be both a blessing and a curse of Wolfgang. On the positive side, he encountered a portion of society that was to be his future bread and butter; he learned very directly at that tender age how to behave at court and what treatment was commonly accorded to entertainers of aristocracy.

To be forewarned was to be forearmed. He also met Johann Christian Bach, the twenty-nine-year-old son of old Johann Sebastian; from this new friend he learned new ways of thinking about music, new styles and sounds that he absorbed like a sponge and merged into his own early compositions.

On the negative side, the journey was immensely perilous to the youngsters. Undoubtedly debilitated by overland coach travel, miserable weather, inconsistent lodging, and the fatigue of public demonstrations of their skills, both Wolfgang and Nannerl became seriously ill, Wolfgang particularly so for about four weeks. This bout of sickness, coming only two years after he had contracted smallpox, weakened his constitution and by modern reckoning greatly contributed, in the long run, to his early death.

Later tours to Vienna and Italy brought honor to the teenage musical genius, whose compositions were beginning to be recognized as equal in skill to his performance. Leopold's teaching was supplemented by the master of counterpoint, Padre Martini; Europe's composers and performers were Mozart's meat and drink in this period. Wolfgang learned fluent Italian and corresponded with Nannerl in that language. In spite of greetings he sent through Nannerl to "all my good friends," his life and artistic growth were dominated by Leopold, and his principal society was the circle of his family.

Mozart in Bologna to his sister, March 24, 1770: ...Please write and tell me who is singing in the oratorios and let me know their titles as well... I shall soon send you a minuet which Mr. Pick danced in the theatre and which everyone danced to afterwards at the feast di ballo in Milan, solely in order that you may see how slowly people dance here. The minuet itself is very beautiful. It comes, of course, from Vienna and was most certainly composed by Deller or Starzer. It has plenty of notes. Why? Because it is a stage minuet which is danced slowly. The minuets in Milan, in fact the Italian minuets generally, have plenty of notes, are played slowly, and have several bars, e.g., the first part has sixteen, the second twenty or twenty-four.

In Parma we got to know a singer and heard her perform very beautifully in her own house-the famous Bastardella who has 1) a beautiful voice, 2) a marvelous throat, 3) an incredible range. While I was present she sang the following notes and passages.... [Anderson, p. 121]

In Parma we got to know a singer and heard her perform very beautifully in her own house-the famous Bastardella who has 1) a beautiful voice, 2) a marvelous throat, 3) an incredible range. While I was present she sang the following notes and passages.... [Anderson, p. 121]

Suffice it to say that with the exception of his own sister and the family servants, Wolfgang's association with other children of his age appears to be infrequent at best; no letters remain to anyone other than his own family members during his teens, and references in his letters to others of his age are minimal. In the realm of professional advancement, he was doing very well, having at the age of sixteen been appointed Konzertmeister to the newly installed Archbishop of Salzburg, Hieronymus, Count of Colloredo.

The consistent focus of Wolfgang's life was his music. Little wonder that during a two-week-long concert-associated visit to his uncle's home in Augsburg in 1777, his acquaintance with his fifteen-year-old cousin, Anna Maria Thekla, provided a basis for later outlets for his adolescent imagination. Wolfgang's correspondence to her after his return to Salzburg abounds in vulgarities; many of these passages have been appropriated by Shaffer as Mozart's banter not with his cousin but with Constanze, whom he had not yet met! This kind of bantering was not, evidently, exceptional within the Mozart family, nor, it appears, in the Salzburg region. In her preface to the Mozart family letters, Emily Anderson includes a short letter from Frau Mozart, employing just such language in what was evidently meant as a whimsical, funny little rhyme. [Anderson, p. xvi, n. 3] The humor was clearly intended to amuse family members, and undoubtedly Frau Mozart would not have expected generations of strangers to have read this intimate message. In Mozart's adult life only his wife and a few of his closest associates were ever privy to such letters.

It may not come as a surprise that, in the year following the correspondence with his cousin, Wolfgang became deeply infatuated with a fifteen-year-old singer, Aloysia Weber. He was so strongly attracted to her, so intent upon helping her advance her performing career, that his letters to his father betrayed an intensity that shook Leopold deeply.

Wolfgang in Mannheim to Leopold, February 4, 1778: ...In the evening, Saturday evening, we went to Court, where Mlle. Weber sang three arias. I say nothing about her singing-only one word, excellent! I wrote to you the other day about her merits; but I shall not be able to close this letter without telling you something more about her, for only now have I got to know her properly and as a result to discover her great powers.... I propose to remain here and finish entirely at my leisure that music for De Jean... I can stay here as long as I like and neither board nor lodging costs me anything. In the meantime Herr Weber will endeavor to get engagements here and there for concerts with me, and we shall then travel together.... I have become so fond of this unfortunate family that my dearest wish is to make them happy; and perhaps I may be able to do so. My advice is that they should go to Italy. So now I should like you to write to our good friend Lugiati, and the sooner the better and enquire what are the highest terms given to a prima donna in Verona.... As far as [Aloysia's] singing is concerned, I would wager my life that she will bring me renown. Even in a short time she has greatly profited by my instruction, and how much greater will the improvement be by then! I am not anxious either about her acting. If our plan succeeds, we, M. Weber, his two daughters [Aloysia and Josefa] and I will have the honor of visiting my dear Papa and my dear sister... My mother [who was in Mannheim with Wolfgang] is quite satisfied with my ideas... [Anderson, pp. 460-463.]

Wolfgang's obvious vulnerability to a beautiful, well-disciplined voice and a charming young woman engaged his open and generous nature. Leopold's response to the letter was a resounding negative. To him, Aloysia was no more than a would-be parasite waiting only to soar to fame on Wolfgang's coattails. He insisted that his son continue his planned travels in search of a lucrative position and leave the siren to some other prey. Wolfgang obeyed. But his day of rebellion was not far off.

Wolfgang, now in his early twenties, was chafing under the burden of his obligation to the Archbishop of Salzburg, whose artistic needs were simple and clearly defined for his composer. Mozart's musical mind was light-years in advance, and his international experience far exceeded the standard for his official status as the archbishop's servant. A collision course was unavoidable. Wolfgang held his peace for several years, touring Paris, where his mother died, and later Munich, and broadening his acquaintance with the active musical world. In 1781, having just achieved a momentous success in Munich with his opera Idomeneo, he received the archbishop's summons to attend him in Vienna. Incensed that his musical work was so little regarded, Mozart raced to Vienna and confronted Colloredo's chamberlain, Count Arco. Bitter accusations on both sides led to a simultaneous resignation and dismissal from the archbishop's service; Wolfgang's description in letters to his father reconstruct the event vividly. Leopold, having originally sponsored his son and having seen to his reinstatement after Wolfgang's long absences, tried frantically to get Wolfgang to reconsider his action, to submit himself for the archbishop's reconsideration. Wolfgang adamantly remained independent of Colloredo. This was the first of only two instances in which he refused to acquiesce to his father's instruction in a life-shaping event.

The second had to do with his marriage.

The second had to do with his marriage.

It was to come as a shock, certainly, to Leopold when, on the heels of the Colloredo debacle, Wolfgang informed him from Vienna of his attraction to another of the Weber daughters, Aloysia's younger sister Constanze. Heaping insult on irony, this Weber daughter had only a fragment of her sister's musical talent to recommend her, and must therefore have posed an even greater threat to Wolfgang's career. Moreover, after Leopold initially warned his son to leave off his nonsense and move from the Weber's house where he had lodging, Wolfgang relocated but clearly showed no inclination to drop his association with Constanze, even in light of her guardian's attempt to keep him from the now fatherless young woman. After nearly two years of friendship and courtship, Mozart wrote to Leopold of his intention to marry Constanze, and asked for Leopold's blessing. Leopold's response was not forthcoming. Wolfgang renewed and intensified his plea for his father's consent to the marriage, which by then had been planned for a specific date. There appears to have been a mad scramble to rescue Constanze from arrest because she had moved out of her mother's house without permission, and Frau Weber became distraught over the seeming impropriety of her behavior. Wolfgang reported to Leopold that the wedding had occurred on the date when he had expected to receive his father's letter of approval knowing that he would, in the end, agree.

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, July 25, 1781: I repeat that I have long been thinking of moving to another lodging, and that too solely because people are gossiping. I am very sorry that I am obliged to do this on account of silly talk, in which there is not a word of truth. I should very much like to know what pleasure certain people can find in spreading entirely groundless reports. Because I am living with them [Frau Weber and her three unmarried daughters], therefore I am going to marry the daughter [Constanze]. There has been no talk of our being in love. They have skipped that stage. No, I just take rooms in the house and marry. If ever there was a time when I thought less of getting married, it is most certainly now.... I will not say that, living in the same house with the Mademoiselle to whom people have already married me, I am ill-bred and do not speak to her; but I am not in love with her. I fool about and have fun with her when time permits (which is only in the evening when I take supper at home, for in the morning I write in my room and in the afternoon I am rarely in the house) and-that is all. If I had to marry all those with whom I have jested, I should have two hundred wives at least... [Anderson, pp. 782-783.]

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, December 15, 1781: ...Dearest father! You demand an explanation of the words in the closing sentence of my last letter! Oh, how gladly would I have opened my heart to you long ago, but I was deterred by the reproaches you might have made me for thinking of such a thing at an unseasonable time-although indeed thinking can never be unseasonable.... You must, therefore, allow me to disclose to you my reasons, which, moreover, are very well founded. The voice of nature speaks as loud in me as in others, louder, perhaps, than in many a big strong lout of a fellow. I simply cannot live as most young men do in these days. In the first place, I have too much religion; in the second place, I have too great a love of my neighbor and too high a feeling of honor to seduce an innocent girl; and in the third place, I have too much horror and disgust, too much dread and fear of diseases and too much care for my health to fool about with whores. So I can swear that I have never had relations of that sort with any woman... I am well aware that this reason (powerful as it is) is not urgent enough. But owing to my disposition, which is more inclined to a peaceful and domesticated existence than to revelry, I who from my youth up have never been accustomed to look after my own belongings, linen, clothes and so forth, cannot think of anything more necessary to me than a wife. I assure you that I am often obliged to spend unnecessarily, simply because I do not pay attention to things. I am absolutely convinced that I should manage better with a wife (on the same income which I have now) than I do by myself.... But who is the object of my love? Do not be horrified again, I entreat you. Surely not one of the Webers? Yes, one of the Webers-but not Josefa, nor Sophie, but Constanze, the middle one... [Anderson, pp. 782-783.]

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, July 27, 1782: ...Dearest, most beloved father, I implore you by all you hold dear in the world to give your consent to my marriage with my dear Constanze. Do not suppose that it is just for the sake of getting married. It that were the only reason, I would gladly wait. But I realize that it is absolutely necessary for my own honor and for that of my girl, and for the sake of my health and spirits. My heart is restless and my head confused; in such a condition how can one think and work to any good purpose? And why am I in this state? Well, because most people thing that we are already married. Her mother gets very much annoyed when she hears these rumors, and, as for the poor girl and myself, we are tormented to death... [Anderson, p. 810.]

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, July 31, 1782: ...In the meantime you will have received my last letter; and I feel confident that your next will contain your consent to my marriage. You can have no objection whatever to raise-and indeed you do not raise any. Your letters show me that. For Constanze is a respectable, honest girl of good parentage, and I am able to support her. We love each other-and want each other... [Anderson, p. 811.]

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, August 7, 1782: You are very much mistaken in your son if you can suppose him capable of acting dishonestly. My dear Constanze-now, thank God, at last my wife [as of August 4}-knew my circumstances and heard from me long ago all that I had to expect from you. But her affection and her love for me were so great that she willingly and joyfully sacrificed her whole future to share my fate. I kiss your hands and thank you with all tenderness which a son has ever feel for a father, for your kind consent and fatherly blessing... Having waited two post-days in vain for a reply and the ceremony having been fixed for a day by which I was certain to have received it, I was married by the blessing of God to my beloved Constanze. I was quite assured of your consent and was therefore conforted. The following day I received your two letters at once... [Anderson, pp. 812-813.]

Leopold's delay in acknowledging the couple's all-too-clearly unalterable intention placed a heavy burden on the remaining years of his relationship with his son. Wolfgang's determination to go through with the relationship with the marriage, even without his father's blessing, signaled a late-blooming independence from Leopold's guidance and control which cost him dearly. The tone of Wolfgang's subsequent letters to his father carries an appeal in it, a desire to appease Leopold's displeasure over such willfulness; he would continue to seek to assure an increasingly critical Leopold of his devotion for the five remaining years of his father's life. The twenty-six-year-old composer was also now without the economic protection of formal patronage.

Mozart's Vienna years had begun boldly and successfully, on the whole. His circle of friends, professional colleagues, and students expanded widely. He made many trips to cities such as Linz and Prague with the assurance of his musical and social prominence. He was well accepted by the Emperor Joseph II and many of his court, albeit without a significant appointment there at first. He found an avenue for his idealism in Freemasonry, a society which from late 1784 until only weeks before his death held his interest and received the benefit of his compositional genius. His productivity during the Vienna years was enormous: six major operas, seven symphonies, seventeen piano concertos alone (besides those for other instruments), and abundant chamber works poured forth from 1781 until his death ten years later. German opera had been given a chance for life because Joseph II determined to support a nationalistic art trend. Mozart's first Viennese opera, The Abduction from the Seraglio, of 1783, was not only a popular success but proof that opera in German was musically viable. The pro-Italian cabal in Vienna (particularly at court), however, saw in this abundance and genius a threat to its own security, and began to take action. In 1786, Mozart's Marriage of Figaro succumbed to the intrigue of the Italian singers and composers in Vienna. Regardless of the ecstatic reception given both Figaro and the premiere of Don Giovanni in Prague, Vienna was closing down to Mozart.

The last five years of Mozart's life were increasingly hard. Four of the six children born to Wolfgang and Constanze died in infancy. Constanze suffered a number of bouts of illness requiring cures at a medicinal spa outside Vienna. Although Mozart had been named Gluck's successor to the post of the Emperor's Kammermusicus, his stipend was only a little over one-third that of Gluck. The position required a stream of small entertainment pieces, hardly challenging to Mozart's creativity. Commissions became more and more scarce, and the once long lists of subscribers to his concerts drew, in 1789, only one name: that of the staunchest of his moneyed supporters, Baron Gottfried van Swieten. Fortunately, van Swieten was in a position to offer Mozart limited private commissions for his pet projects of performances of older music, but the income from these events was hardly enough to keep Mozart's family secure. Mozart's letters to Michael Puchberg, a fellow-Mason, reveal a real desperation during these years in eloquent and poignant requests for loans. Recently, H.C. Robbins Landon has suggested that, regardless of his impracticality with money, Mozart was somewhat better off than history has painted him. There can be no doubt, though, that the years from 1788 on were difficult, and that Mozart was hard-pressed to secure a post with substantial income.

Wolfgang in Vienna to Leopold, June 18, 1783: Congratulations, you are a grandpapa! Yesterday, the 17th, at half past six in the morning my dear wife was safely delivered of a fine study boy, as round as a ball.. And now the child has been given to a foster-nurse against my will, or rather, at my wish! For I was quite determined that whether she should be able to do so nor not, my wife was never to feed her child. Yet I was equally determined that my child was never to take the milk of a stranger! I wanted the child to be brought up on water, like my sister and myself. However, the midwife, my mother-in-law and most people here have begged and implored me not to allow it, if only for the reason that most children here who are brought up on water do not survive, as the people here don't know how to do it properly. That induced me to give in, for I shouldn't like to have anything to reproach myself with.... [Anderson, pp. 841-842.]

Wolfgang to Michael Puchberg, July 12, 1789: Dearest, most beloved Friend and most honorable B[rother of the] O[rder]. Great God! I would not wish my worst enemy to be in my present position. And if you, most beloved friend and brother, forsake me, we are altogether lost, both my unfortunate and blameless self and my poor sick wife and child.... Good God! I am coming to you not with thanks but with fresh entreaties! Instead of paying my debts I am asking for more money! If you really know me, you must sympathize with my anguish at having to do so. I need not tell you once more that owing to my unfortunate illness I have been prevented from earning anything. But I must mention that in spite of my wretched condition I decided to give subscription concerts at home in order to be able to meet at least my present great and frequent expenses, for I was absolutely convinced of your friendly assistance. But even this has failed. Unfortunately Fate is so much against me, though only in Vienna, that even when I want to, I cannot make any money. A fortnight ago I sent round a list of subscribers and so far the only name on it is that of the Baron van Swieten!... [July 14] O God!-I can hardly bring myself to dispatch this letter!-and yet I must! If this illness had not befallen me, I should not have been obliged to beg so shamelessly from my only friend. Yet I hope for your forgiveness, for you know both the good and the bad prospects of my situation. The bad is temporary; the good will certainly persist, once the momentary evil has been alieviated.... [Anderson, pp. 929-931.]

Joseph I died in 1790, and his brother Leopold acceded to the throne of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire. More practical than his sibling, Leopold faced the problem of governing his nation only two years after his sister Marie Antoinette and her husband Louis XVI had been coerced from power in France. Leopold had little time for entertainment. Mozart's petition for a higher position in the new court was denied, but his later request to serve as Kapellmeister at St. Stephen's Cathedral was eventually approved by the city officials. A tour of North German cities, including Leipzig and Berlin, had yielded no appointments in 1789, but at the end of 1790 an offer came from London with a promise of a remunerative position there. Mozart may have been too exhausted to accept it, or too concerned for Constanze's health; in any case, he remained in Vienna.

Three new commissions in 1791 gave some hope. The first, The Magic Flute, was to be a popular entertainment for a suburban theater. The second, The Clemency of Titus, was the principal celebrative piece for Leopold's coronation in Prague as King of Bohemia. The third was for a setting of the Requiem Mass, for a stranger representing a patron who had lost someone dear. Constanze was pregnant with their sixth child and taking the waters at Baden.

Mozart in Vienna to Constanze, June 11, 1791: ...I cannot tell you what I would not give to be with you at Baden instead of being stuck here. From sheer boredom I composed today an aria for my opera [The Magic Flute]. I got up as early as half past four. Wonderful to relate, I have got back my watch-but-as I have no key, I have unfortunately not been able to wind it. What a nuisance! Schulmbla! That is a word to ponder on. Well, I wound our big clock instead. Adieu-my love! I am lunching today with Puchberg. I kiss you a thousand times and say with you in thought: 'Death and despair were his reward!' ...See that Karl [their son] behaves himself. Give him kisses from me. Take an electuary if you are constipated-not otherwise. Take care of yourself in the morning and evening, if it is chilly. [Anderson, p. 953-954.]

From the end of August, Mozart's own health declined radically. By late November he was bedridden and composed despite dreadful pain, bloating and fever. Modern diagnosis of his symptoms indicates that the cause of death was kidney failure associated with Schönlein-Henoch Syndrome-essentially a massive failure of his body's systems (The interested reader should see Peter J. Davies' "Mozart's Illnesses and Death" in Musical Times, August and October, 1984, for a detailed explanation just how shockingly poor Mozart's health was throughout his life). Death came just before 1:00 am on December 5.

Mozart's last hours had been spent attempting to complete the Requiem commission with he help of his pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who eventually was credited with finishing the work. Besides Constanze, only her sister Sophie was present at the actual time of his death. Mozart's body was blessed outside St. Stephen's Cathedral, probably the next day. It was then taken outside the walls of Vienna to St. Marx Cemetery, where it was placed in a common grave, in accordance with the practice instituted by Joseph II to maintain public health in the wake of Vienna's relatively recent encounter with the plague.

Looking back at Mozart's life and experience, we must certainly wonder at the almost violent swings of fortune that this extraordinary composer sustained. International adulation in his youth gave way to increasing resistance from a conservative patron. Apparent liberation from a stifling employer and parental management and subsequent success in public and court enterprises reverted to limited employment and changing personal and political pressures in Vienna. Through it all, Mozart continued to compose. Further, the music which he composed in some of the darkest hours maintains the same esthetic as the music he composed in his least troubled times. The uniformity of control of musical content is Mozart's technical hallmark. Even the most treacherously chromatic passages, such as the Adagio opening of the "Dissonant" C-major string quartet, are grounded in a musical logic that defied old Leopold's eyes but were perfectly comprehensible to his ear. In these matters lie clues to Mozart's genius and taste.

Remarkable, too, is the fact that in his own time Mozart was recognized as a genius by a number of major figures, yet this recognition served to bring him very little financial security. His maverick rejection of the worthy patronage of the Archbishop of Salzburg undoubtedly prompted some in power to hold him at a distance. Certainly his self-confidence and belief in the value of his artistic products would be interpreted as arrogance. In spite of the intrigues and political deals, however, Mozart's music clearly made its mark, even on his enemies and detractors. The distinctive detail and fluidity of his style and its richness of expression and clarity were far beyond the norm of his time.

In 1785, Leopold Mozart proudly wrote to Nannerl, now Frau von Berchtold zu Sonnenberg, that no less a person that the world-renowned composer Joseph Haydn had said to him, "Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name. He has taste, and, what is more, the most profound knowledge of composition." [Anderson, p. 886] Haydn's comment about Wolfgang's having the "most profound knowledge of composition" rings true to us today. We have become aware of the ingenuity in his construction of music-its integrated coherence, its refinement of expressive articulation, and its diverse and often haunting sonorities. We ought not, however, take as an offhand statement Haydn's reference to Wolfgang's taste, for in this one term the senior, insightful master named that ineffable quality by which his younger colleague ascended to a level of art that exists as its own field of reference, inimitable, a law unto itself.

There is no reason to believe that Mozart achieved his musical brilliance without effort. His own and his family's correspondence describes quite vividly the extensive hours of practice, performance, teaching, and composing in the course of a day. There were even instances in which, as an adult, Mozart literally set himself to study a particular type of composition, notably that of J.S. Bach, in order to master it for his own use. Even simple pastimes served as exercises for the process of composition. Reversed order of letters in a word, cryptographic exchanges of letters in the name of some political personage, nonsense rhymes, and acronymic references to the wealthy and powerful are all present in Mozart's letters, and analogues to all these exist in his compositional technique. The intensity with which he engaged in music-making is hardly common; that he thought in musical concepts is undoubtedly true.

The eighteenth century was fascinated by the unquantifiable characteristics genius and taste. In an era heavily laden with natural law, these qualities were elusive and inexplicable: they could neither be reduced to mathematical formulae nor accounted for by education or personal effort. Isolated from the scientific, political and social discoveries of the time, these characteristics remained a source of universal awe; for although no one seemed able to define them, genius and taste were incontrovertibly discernible in a creative work. The child Wolfgang, recognized as a prodigy largely because of his performing ability, was considered an oddity of his father's training. The adult Wolfgang was an ungovernable paradox of commonness and refinement, vulgarity and gentility. For generations after his death he would be set in a special niche and regarded as somehow other than ordinarily human. This unfortunate legacy of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century cult of the genius has already found its polar opposite in the demythologizing portrait of Mozart in Shaffer's play.

Perhaps Mozart conjures up a better-balanced picture of himself through his own words of October 7, 1791, to Constanze, who was again at Baden: ...I have this moment returned from the opera [The Magic Flute], which was as full as ever. As usual the duet 'Mann und Weib' and Papageno's glockenspiel in Act I had to be repeated and also the trio of the boys in Act II. But what always gives me most pleasure is the silent approval! You can see how this opera is becoming more and more esteemed. Now for an account of my own doings. Immediately after your departure I played two games of billiards with Herr von Mozart, the cello who wrote the opera which is running at Schikaneder's theater [his own Magic Flute]; then I sold my nag for fourteen ducats; then I told Joseph [the landlord] to get Primus [a waiter] to fetch me some black coffee, with which I smoked a splendid pipe of tobacco; and then I orchestrated almost the whole of Stadler's rondo [the last movement of the Clarinet Concerto].... [Anderson, p. 968.]

Judith Eckelmeyer © 1991

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.