- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

POULENC: QUATRE MOTETS POUR UN TEMPS DE PÉNITENCE

Quatre Motets Pour Un Temps de Pénitence

by Judith Eckelmeyer

by Judith Eckelmeyer

I. Timor et Tremor

Fear and trembling have come over me, and darkness has fallen on me. Have mercy on me, Lord, have mercy, for my soul trusts in you. God, hear my prayer, for you are my refuge and my strong advocate. Lord, I have called upon you; do not destroy me.

II. Vinea mea electa

My chosen vineyard, I planted you; why have you changed into bitterness so as to crucify me and release Barabbas? I hedged (protected) you, and removed stones from around you, and built a watch tower.

III. Tenebrae factae sunt

It became dark when they crucified Jesus of Judea. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, My God, why have you forsaken me? And bowing his head he gave out his spirit. Exclaiming in a loud voice, Jesus said, Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.

IV. Tristis est anima mea

My soul is sorrowing to death. Stay here, and watch with me. Soon you will see a crowd which will surround me. You will take flight, and I will go to be sacrificed for you. Behold, the hour is near and the son of man will be given into the hands of sinners.

Fear and trembling have come over me, and darkness has fallen on me. Have mercy on me, Lord, have mercy, for my soul trusts in you. God, hear my prayer, for you are my refuge and my strong advocate. Lord, I have called upon you; do not destroy me.

II. Vinea mea electa

My chosen vineyard, I planted you; why have you changed into bitterness so as to crucify me and release Barabbas? I hedged (protected) you, and removed stones from around you, and built a watch tower.

III. Tenebrae factae sunt

It became dark when they crucified Jesus of Judea. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, My God, why have you forsaken me? And bowing his head he gave out his spirit. Exclaiming in a loud voice, Jesus said, Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.

IV. Tristis est anima mea

My soul is sorrowing to death. Stay here, and watch with me. Soon you will see a crowd which will surround me. You will take flight, and I will go to be sacrificed for you. Behold, the hour is near and the son of man will be given into the hands of sinners.

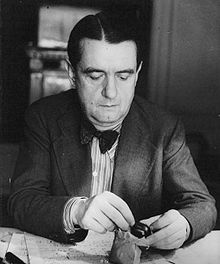

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) was born and raised in Paris. He learned piano as a child from his mother, and was introduced through her and her brother into a highly secular world of contemporary French literature and music. Poulenc’s father, whom he described as a “deeply religious but liberal” Catholic from the south of France, died in 1917, after which Francis moved in the spheres of his mother’s secular, cosmopolitan world.

As a teen, he studied the piano music of Debussy and Ravel, then met Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud—three of Les Six—and Eric Satie, their older friend and guide to the avant-garde. At the age of 18 he dedicated his first published work to Satie and became associated with the iconoclastic Six. Although he eventually studied composition formally, it was with private teachers rather than in a classically structured program; he famously progressed no further in counterpoint than Bach’s chorales in spite of having met and conversed with Schoenberg and his pupils in 1921 in Vienna. In this highly individualistic and open-ended development, Poulenc acquired the diversity of resources that would characterize his music: sensitivity to harmonic and tonal color, melodic freedom, and the “language” of popular music current in Parisian cafes and theaters.

Poulenc’s world changed in 1936 when his friend, composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud, was killed in a car accident. In the wake of this tragedy Poulenc retired to Rocamadour, a pilgrimage town in the southern region from which his father had come. There, Poulenc returned to religious faith. His very first sacred choral piece, “Litanies to the Black Virgin” of 1936, is a setting for women’s and children’s voices of recitations honoring the Virgin who is represented by a blackened wood statue in the church of Notre Dame in Rocamadour. Other sacred choral works followed soon after and appear throughout the rest of his life.

Poulenc composed the Four Motets for a Penitential Time shortly after finishing his Mass in G in 1937; “Vinea mea electa”, “Tenebrae factae sunt”, and “Tristis est anima mea” were completed in 1938 and “Timor et Tremor” in 1939. The texts are very old poems conflating and adapting Biblical passages from Psalm 55 (“Timor et tremor”), the Gospels (“Tenebrae factae sunt” and “Tristis est anima mea”), and Isaiah 5 (“Vinea mea electa”).

If one had no idea of the subject matter, one might say the motets were studies in varieties of dissonance. Yet as we know, dissonance comes in many flavors, from intensely bitter, to harsh, to melancholy, to poignantly sweet. To attain his remarkable chord constructions in these motets, Poulenc almost everywhere divided the traditional SATB parts. He was a master at choosing just the right combination of pitches to help define the emotional values of the texts. He also intensified the choral effects through varying the vocal ranges. Poulenc thought his sacred choral music represented “the best and most genuine part” of himself; indeed, all of the harmonic and textural attributes in these motets reflect his absolute dedication to reaching into the depths of the texts.

Each penitential motet has remarkable sonic detail. Some examples to listen for:

In “Timor et tremor”, “darkness” lies in very low ranges for altos, tenors and basses. In the plea to avoid ruin, at the end, the word “Domine”—“Lord”—is set to shocking dissonance, and the word “confundar”—“ruin”—is a treacherous chromatic passage. (Many a chorister would see a life lesson here!)

“Vinea mea electa”, the gardener’s song of love for his perfidious vineyard, begins with lush, full, lovely harmonies but becomes intensely dissonant with the bitterness of betrayal—the beloved radically changes, crucifying her caring husbandman and releasing the criminal Barabbas.

“Tenebrae factae sunt” begins with the darkness of the low alto and bass voices, reaching to extraordinary outbursts at “Jesus exclaimed”. Jesus’s words, devastatingly restrained in their setting, are followed by the depiction of his bowing his head and yielding his spirit.

“Tristis est anima mea” is set for the usual four choral parts with a soprano soloist, who begins the piece with the profoundly sorrowful words Jesus speaks to his disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane. Poulenc’s setting of Jesus’s prediction of the disciples’ flight is vivid, and Jesus’s first statement that he is going to be sacrificed for them is tumultuous. But Poulenc gives the second presentation of this statement in the full, rich eight-voice chorus, with the luminous soprano transforming Jesus’s words into light.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

Each penitential motet has remarkable sonic detail. Some examples to listen for:

In “Timor et tremor”, “darkness” lies in very low ranges for altos, tenors and basses. In the plea to avoid ruin, at the end, the word “Domine”—“Lord”—is set to shocking dissonance, and the word “confundar”—“ruin”—is a treacherous chromatic passage. (Many a chorister would see a life lesson here!)

“Vinea mea electa”, the gardener’s song of love for his perfidious vineyard, begins with lush, full, lovely harmonies but becomes intensely dissonant with the bitterness of betrayal—the beloved radically changes, crucifying her caring husbandman and releasing the criminal Barabbas.

“Tenebrae factae sunt” begins with the darkness of the low alto and bass voices, reaching to extraordinary outbursts at “Jesus exclaimed”. Jesus’s words, devastatingly restrained in their setting, are followed by the depiction of his bowing his head and yielding his spirit.

“Tristis est anima mea” is set for the usual four choral parts with a soprano soloist, who begins the piece with the profoundly sorrowful words Jesus speaks to his disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane. Poulenc’s setting of Jesus’s prediction of the disciples’ flight is vivid, and Jesus’s first statement that he is going to be sacrificed for them is tumultuous. But Poulenc gives the second presentation of this statement in the full, rich eight-voice chorus, with the luminous soprano transforming Jesus’s words into light.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2016

Poulenc’s “Quatre motets pour un temps de pénitence”: Canterbury Cathedral 1988 (Allan Wicks)

From an audio cassette entitled “Francis Poulenc - A Celebration”, recorded in Canterbury Cathedral in 1988 but not issued until 1992. This was Allan Wicks’ very last recording with the choir.

From an audio cassette entitled “Francis Poulenc - A Celebration”, recorded in Canterbury Cathedral in 1988 but not issued until 1992. This was Allan Wicks’ very last recording with the choir.

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.