- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

Bach: Cantata 4

On Hearing J. S. Bach's Cantata 4: Christ Lag In Todesbanden

By Judith Eckelmeyer

Introduction: Bach

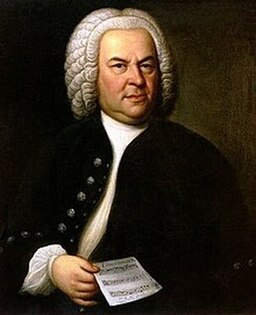

A remarkable person entered the world of music in 1685—Johann Sebastian Bach. Most people today know him as an extraordinary composer, but in his own time he was also a renowned performer, respected by outstanding musicians such as Georg Frideric Handel, an exacting and insightful teacher especially of composition, a sought-after consultant on organ construction, and a student of theology and Luther’s teachings. Formidable as this description sounds, though, Bach was also an attentive and affectionate husband and a devoted father to his 20 children. Born in the hillside town of Eisenach in Thuringia, Germany, into a family of musicians, Sebastian (as he was called) far exceeded his forebears, relatives, and four musical sons in the quality and quantity of the music he wrote.

A remarkable person entered the world of music in 1685—Johann Sebastian Bach. Most people today know him as an extraordinary composer, but in his own time he was also a renowned performer, respected by outstanding musicians such as Georg Frideric Handel, an exacting and insightful teacher especially of composition, a sought-after consultant on organ construction, and a student of theology and Luther’s teachings. Formidable as this description sounds, though, Bach was also an attentive and affectionate husband and a devoted father to his 20 children. Born in the hillside town of Eisenach in Thuringia, Germany, into a family of musicians, Sebastian (as he was called) far exceeded his forebears, relatives, and four musical sons in the quality and quantity of the music he wrote.

Bach spent most of his life composing and performing music for Lutheran churches in Germany. He began at age 18 as an organist in Arnstadt, moved to Mühlhausen three years later, then quickly received an appointment as Court Organist and eventually Concertmaster to the Duke of Weimar (1707-1717).

After a period in a secular court appointment in Cöthen (1717-1723), he assumed the position of Cantor (music director) at St. Thomas Church in the large city of Leipzig in Saxony, Germany.

As Thomaskantor, Bach was also responsible for music at the three other principal churches in the city as well as at the town’s civic events and Leipzig University’s celebrations.

He was also obligated to teach Latin and catechism to the students at the school of St. Thomas Church. The younger boys of the Thomasschule, whom Bach trained, sang the treble parts in the cantatas, motets, and Mass settings that Bach composed for the services there; older students and men of the various congregations sang the tenor and bass parts. Bach’s Leipzig career continued until he died in 1750.

PART I: BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON CANTATA 4

During his 41 years as a church musician, Bach wrote an enormous amount of sacred music, a large portion of it as cantata. In his time, the sacred cantata for the Lutheran Church was changing from an earlier motet style or vocal concerto to a kind of mini-oratorio consisting of recitatives, arias, choruses, and chorales (hymns). Composed around the topic of the day in the church calendar, the cantata reinforced the message of the scripture for the day and supplemented the pastor’s teaching. Bach wrote cantatas while at each of his church appointments. By far the greatest number come from his time in Leipzig, where he wrote a cantata for the Sunday services (and some major church holidays) every week for at least four years. More than 200 of his cantatas (reckoned as about 60% of the estimated total for his career) are extant today.

The text of a cantata was usually the work of a librettist interested in sacred poetry, who would interweave the day’s scriptural passages or hymn texts with his own new meditative passages (to be set as arias). Organ and other instruments provided an accompaniment suitable for the vocal performing group and appropriate to the tenor of the ecclesiastical season. The cantata, taking from about 20 to 30 minutes to perform, would be a part of the Sunday service. Almost every cantata Bach wrote concluded with a chorale (hymn) verse set in four-part harmony in such a way that the congregation would be able to join in singing at least the melody.

The text of a cantata was usually the work of a librettist interested in sacred poetry, who would interweave the day’s scriptural passages or hymn texts with his own new meditative passages (to be set as arias). Organ and other instruments provided an accompaniment suitable for the vocal performing group and appropriate to the tenor of the ecclesiastical season. The cantata, taking from about 20 to 30 minutes to perform, would be a part of the Sunday service. Almost every cantata Bach wrote concluded with a chorale (hymn) verse set in four-part harmony in such a way that the congregation would be able to join in singing at least the melody.

Genesis and early performances of Cantata 4

Cantata 4, Christ lag in Todesbanden (Christ Lay in the Bonds of Death) is unique among Bach’s works. It is a seven-movement setting of the Lutheran chorale of the same name, preceded by a short instrumental introduction, or sinfonia. Because all movements contain the chorale melody and text, this cantata is termed a chorale cantata; it is the only one ofits type that Bach wrote, although in several of his other cantatas he used chorale text and/or melody in a number of movements.

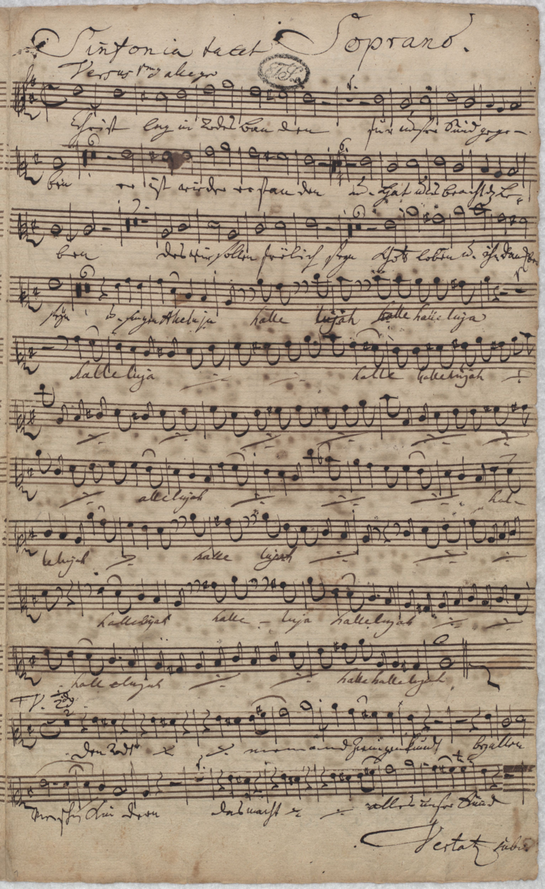

According to recent studies, Bach composed his Cantata 4 for Easter, 1707, while he was at Mühlhausen. The scoring was for a 4-part chorus consisting of sopranos, altos, tenors, and basses (SATB) and an instrumental accompaniment of two violins, two violas, and continuo (most likely organ and cello). Nearly two decades later, as the newly-appointed cantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, he had the parts recopied in preparation for performance, possibly with some revisions in the process. Watermarks in the paper and the handwriting indicate the date of the new scores to be 1724. In the following year, copyists wrote out new parts for cornetto (a leather-wrapped wooden instrument held vertically, with finger holes like a recorder but a trumpet-like mouthpiece) and three trombones, which doubled the voices. Gerhard Herz, editor of the W. W. Norton Critical Score of Cantata 4 (1967), believes that Bach harmonized the final chorale of the cantata in 1724, making that element the only part of the cantata original in Bach’s Leipzig career. It is certain only that the cantata was performed at the church at Leipzig University on Easter Day in 1724 and 1725. The history of the chorale on which the cantata is based and the style of Bach’s composition are effectively laid out in Herz’s notes and analysis of the movements in the Norton Critical Score. The reader is encouraged to read that for further information.

Bach’s Theological Insights

Brought up in the Lutheran faith, Bach studied both the Bible and the writings of Martin Luther, which include not only translation of the scriptures from Latin, Greek and Aramaic into German, but also extensive commentary on both scripture and liturgy. Bach was so familiar with these resources and so deeply responsive to them that he annotated the margins of his personal Bible with his own insightful comments. The more we study Bach’s music, the clearer it is that in setting sacred text to music Bach was composing as a theologian, expressing the religious thought and meanings of the words with musical imagery.

In the course of this essay we will explore Bach’s symbolic musical working-out of the text and melody of the chorale “Christ lag in Todesbanden” to see how he communicated his view of the meanings of the text.

The Lutheran Chorale

It will help to know at the outset how a Lutheran chorale is organized. Like most hymns, the text consists of a number of verses of poetry. Various rhyme schemes tie the lines of poetry together in each verse. Usually the first and second lines would rhyme; the remainder might rhyme with the first two lines, or it might not. This textual scheme allowed the composer to use what was called a “Bar” (Bogen) form in his music. In Bar form, the first line of melody carries the first line of the poem, then is identically repeated for the second line of the poem, underscoring the rhymed first two lines of poetry. This first melody is called a Stollen or “fore-portion” of the tune; thus, with the repeat for the second line of the verse there were two statements of the Stollen. The melody for the remaining portion of the poem was markedly different from and much longer than the Stollen; it was called the Abgesang, or “following portion” or “concluding portion”.

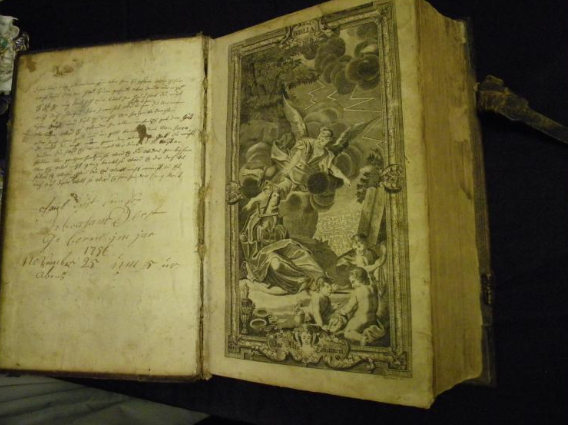

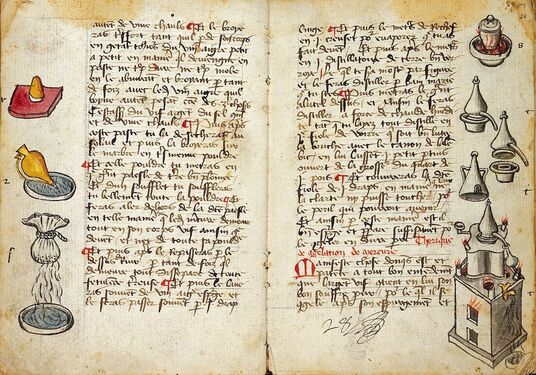

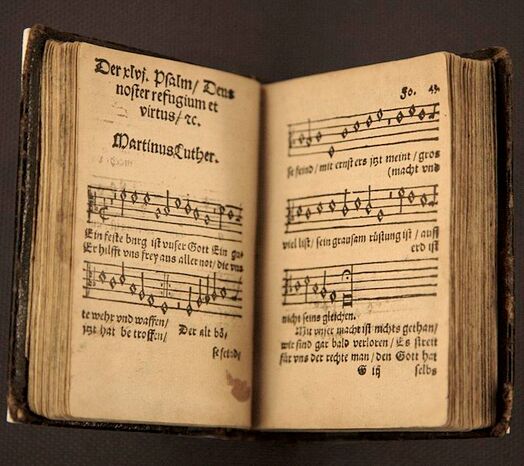

This method of melodic construction developed in the late Medieval era in Germany to set the elevated poetry of the Minnesingers and Meistersingers. Martin Luther, the Protestant reformer who was himself a musician, certainly knew Bar form and adapted it in writing hymns for his reformed German congregations.

One of only very few early printings of Luther's hymn: "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God." There are no known first edition printings left. This book is a second edition, and extremely rare. It is in the holdings of the Lutherhaus museum in Wittenberg, Germany. Photograph by Paul T. McCain. June 2006. Wittenberg, Germany.

In fact, “Christ lag in Todesbanden” is one of several chorales for which Luther wrote both the German text and the melody in the first half of the 16th century. (Although there is some thought that Luther’s colleague Johann Walther was the arranger of the Catholic sequence into a chorale, musicologist Robin A. Leaver, writing “Music and Lutheranism” in The Cambridge Companion to Bach, 1997, specifically alludes to “Luther’s reworking of [the sequence]”, making no mention of a role for Walther in this.) He actually adapted both text and melody from a much older Latin plainchant from the Catholic liturgy for Easter, the sequence prosa “Victimae paschali laudes”, ascribed to Vipo in the first half of the eleventh century. To create this chorale Luther intermixed scriptural passages with passages from the sequence text, although all in German, so that his congregation would understand what they were singing. He also kept a significant, identifiable portion of the music of the old sequence as well, creating what is termed a contrafactum—literally a “made-over” melody. Luther’s simplified and abbreviated version of the sequence melody suited the new text and the needs of the lay congregation who would be singing it. It can hardly be overemphasized that Luther fully expected the people of his congregation to be able to read both the words and music of his chorales; indeed, he believed that through such sacred music the congregation’s religious experience would be heightened and enriched. The chorale was a vehicle for both worship and education, and at another level ensured that musical and language literacy were promoted among the “ordinary” people.

A more detailed examination of the text of “Christ lag in Todesbanden” follows in the “Passover/Easter Congruity” section of this essay. In addition, there will be a side-bar discussion, from David Brodsky, of a relationship between Luther and the city of Mühlhausen as they are likely to have affected Luther’s creation of the chorale’s text.

A more detailed examination of the text of “Christ lag in Todesbanden” follows in the “Passover/Easter Congruity” section of this essay. In addition, there will be a side-bar discussion, from David Brodsky, of a relationship between Luther and the city of Mühlhausen as they are likely to have affected Luther’s creation of the chorale’s text.

II. TEXT CONTENT OF CANTATA 4

To understand Bach’s music in Cantata 4 we must grasp the chorale’s text. Gerhard Herz gives the original German and a close translation at the beginning of his analysis of each movement in the Norton Critical Score and comments on specific words and the general tenor of each verse; these offer valuable insights into the work. In addition, we need to know the connection of the text both to the Jewish context of the Passover and to the Lutheran Christian context of the chorale. The next sections will present the Jewish tradition and then continue with basic Christian symbolism, and then show both as they occur in the text and, finally, in Bach’s setting of the text in Cantata 4.

The Passover Tradition and Cantata 4

The foundation of the text in Cantata 4 is the Passover as an event, as a demonstration of religious doctrine, and as a festival celebration of freedom. The event of the Passover is recorded in the book of Exodus in the Bible. The story, necessary to the content of the chorale at the heart of Bach’s cantata, is presented here briefly:

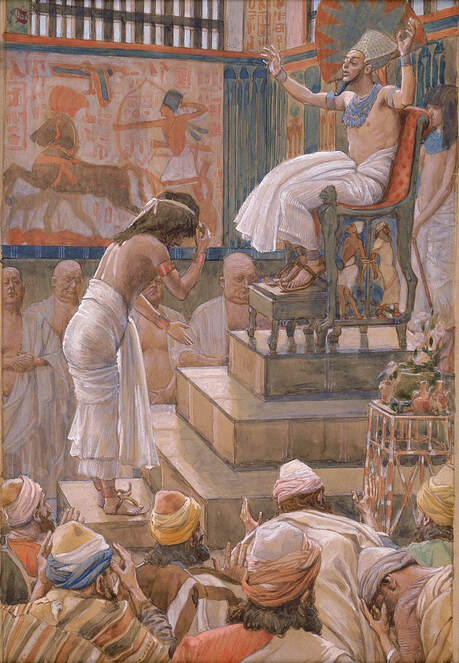

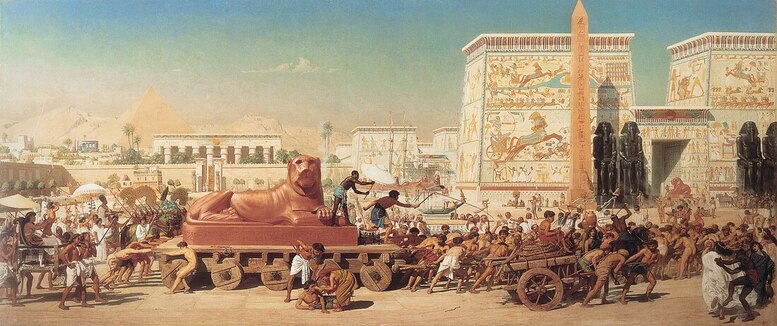

Jacob, also called Israel, was a descendent of Abraham and of a family who worshipped Yahweh, God. Jacob had twelve sons—Joseph and his brothers. Jealous of Joseph because he was Jacob’s favorite, the older brothers sold Joseph to merchant Ishmaelites, who took him with their caravan to Egypt. There, over time, he attained great power and prominence. Eventually, he was his brothers’ and father’s salvation. He brought them to shelter in Egypt when a famine decimated their homeland and effected a reconciliation with them.

According to the Bible, the Hebrews, “the children of Israel”, lived on in Egypt for 430 years. As their numbers grew and the Egyptians’ memory of the great leader Joseph faded, they suffered increasingly under privation and abuse by the Egyptians. To prevent the possibility of the Hebrews outnumbering them or joining their enemies in war, the Egyptians enslaved the Hebrews and instituted particularly harsh conditions of forced labor on them: “…the Egyptians made the children of Israel to serve with rigor: and they made their lives bitter with hard service, in mortar and brick, and in all manner of service in the field…” (Exodus 1:12-14). The Egyptians, hoping to suppress the Hebrews’ population growth, even tried to force the Hebrews’ midwives to kill newborn male children as they delivered them; the midwives, however, evaded the regulation.

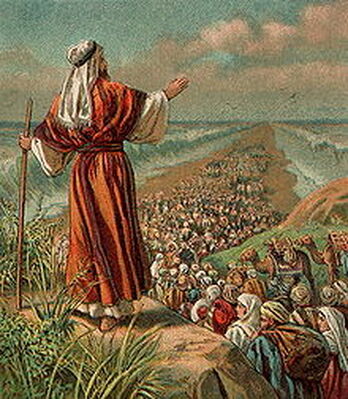

Into this situation was born Moses, who with his brother Aaron acted on Yahweh’s direction to free his people from bondage and bring them out of Egypt to a land promised to them and their descendants. Moses first tried to convince the Egyptian Pharaoh of the power of Yahweh as an inducement to releasing the Hebrew slaves. The inducements came in the form of plagues, but as each plague subsided, Pharaoh’s fear evaporated and he obdurately refused to release the Hebrews.

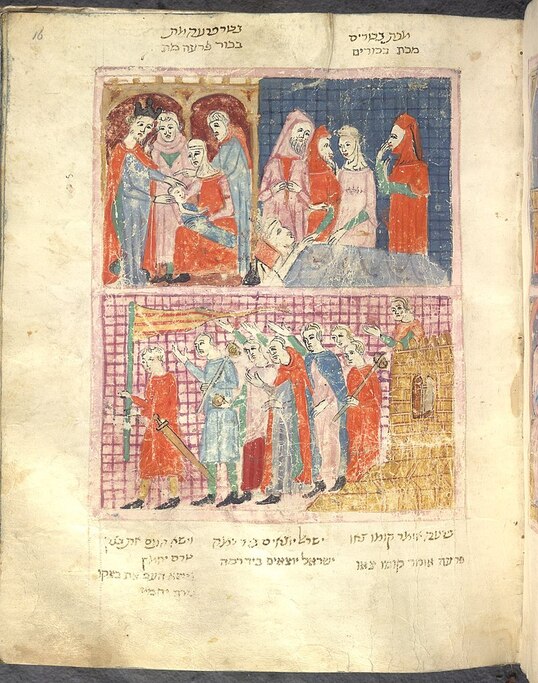

Yahweh, through Moses, promised Pharaoh a final plague: the death of every first-born child of the Egyptians and even of the Egyptians’ servants and cattle. But Yahweh also told Moses to instruct the Hebrews how to prevent this same plague from striking them. Each household was to take a year-old unblemished lamb (or goat’s kid), slaughter it in the appointed evening, then dip a hyssop branch into the blood and use it to sprinkle the lamb’s blood on the side posts and the lintel of the house. Meanwhile, that same night the household was to roast the animal and eat it along with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, and burn up any leftover meat before the next morning. Those eating this meal were to eat it quickly, and be dressed ready to travel, but stay within the house throughout the night until morning. “For Yahweh will pass through to smite the Egyptians; and when he sees the blood upon the lintel, and on the two side-posts, Yahweh will PASS OVER the door, and will not suffer the destroyer to come in unto your houses to smite you. And you shall observe this thing for an ordinance to you and to your sons forever” (Exodus 12:23-24). Pharaoh resisted no longer, but sent the 600,000 Hebrew men and their families out of Egypt. (The events of their departure and 40-year journey to the land promised them over the Jordan River are chronicled in the remainder of Exodus, the books of Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and the first three chapters of Joshua.)

The celebration that is commanded for all time in Exodus 12 is the annual remembrance of the Passover through the week-long observation of the feast of unleavened bread. In addition to the meal of roasted lamb and bitter herbs, Yahweh commanded the Israelites to eat unleavened bread. This is a distinctly different product from raised or leavened bread. As anyone familiar with traditional methods of bread-making knows, usually a small amount of leavening, called “sour dough”, with the yeast still active, is needed as a starter for a new batch. The yeast in the old dough will feed on the new nourishing ingredients and “grow”, decaying or fermenting and forming the gas that makes the dough expand or rise. Unleavened bread, however, is made without the decaying material of the starter or yeast. It is ready to bake in mere moments compared to the hours or days required for leavening to “work” properly before yeast dough can be baked into bread. It is just the thing for a meal being prepared on short notice before a hasty departure from Egypt. It also suggests an affirmation of life through abstinence from any decaying substance.

Out of the telling of the Passover may be drawn principles of a religious or theological nature that will be transmitted into Luther’s hymn text, and thus into Bach’s cantata. The most apparent is that Yahweh ultimately protects and preserves his people, those who experience a unique and dynamic communication with him. The nature of this protection is the second principle: that Yahweh’s people will not suffer the death that is the work of the Destroyer. There is a fine point here which distinguished between ordinary mortality which is common to all human beings and living creatures, and the deliberate eradication of Yahweh’s enemies. In the first case, those physically dead have been in Yahweh’s mind; they are those for whom he cared and to whom he attended and who will, so to speak, be remembered by him even though they cease living in this life. In the case of Yahweh’s enemies, those physically dead have been actively separated from Yahweh, destroyed, disremembered. This most harsh destruction represents more than physical death—it is, in fact, the cessation of being.

The specific features of the Passover celebration that are significant for Bach’s cantata begin with the figure of the lamb, the source of several facets of the symbolism in the cantata. The first is the sacrifice of the pure (“unblemished”) lamb. Its blood has to identify where Yahweh’s faithful live, so the Destroyer will PASS OVER those homes, and then the lamb’s flesh will nourish the protected people, who must roast and eat the meat indoors while all around the Destroyer takes the Egyptians’ first-born. The second feature is the “feast of unleavened bread.” This seven-day period of the celebration is remembered numerically in the cantata’s structure, as is the rejection of decaying matter. Passover is the origin of Christianity’s concept of the bread and wine of the Eucharist as the “body of Christ, the bread of life” and the “blood of Christ, the cup of salvation” (the blood of the lamb protecting the household from the Destroyer). The third is the celebration of life and freedom that the Passover feast represents.

Passover/Easter Congruity

The views that will follow are theological in nature, but they are intended to show my current ideas on the meaning of the text; this can give us a window into the impact of the text on Bach. Even though I will use the terms “us” and “we” in the next two sections, I do so not to assume all readers are Christians, but rather to present a perspective from the standpoint of Christian thinking, and perhaps as Bach might have thought of the texts in preparation for setting them in music.

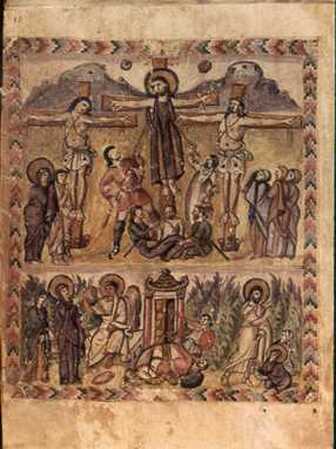

Luther’s chorale text contains symbolic references to the New Testament narrations of Jesus’s death. According to these, the last meal that Jesus and his disciples ate together was the feast of the preparation for the Passover. The following day, Jesus was executed as a criminal. His death thus coincided with the Passover itself, underscoring the metaphor of Jesus as “the Lamb of God”, the paschal (from pesach, Passover) sacrifice. This central symbol of the chorale is biblical, appearing first in the Gospel of John (1:29). As related in the Gospels, the first four books of The New Testament, Jesus’s blood was shed when he was scourged, wounded by a crown of thorns, nailed to a cross, and pierced in the side while hanging on the cross. In Christian theology, Jesus is the Anointed One (Messiah, or Christ), who will deliver his people from Death (see below) with the shedding of his blood. The Christian’s belief in the ongoing spiritual life is reflected in the celebration of Jesus’s resurrection on Easter Day.

Another metaphor attaching to Jesus as the “Lamb of God” relates to the sacrifice of the unblemished lamb at Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement in the Jewish calendar; the chorale alludes to this metaphor in its first verse, in referring to Christ having been “given for our sins,” and in Verse Three, referring to Jesus coming “in our stead” and “doing away with sin.” In this case, Jesus becomes the substitute for the pure lamb ritually slaughtered by the High Priest in the Temple in expiation for the sins of the community in the previous year. The sins were symbolically laid on a “scapegoat” which was driven into the wilderness. The ritual sought atonement with God and a renewal of life for the coming year

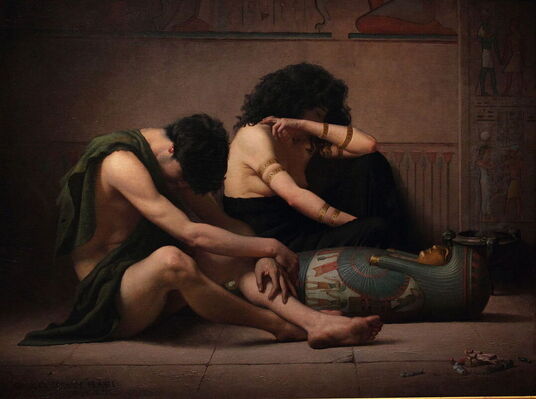

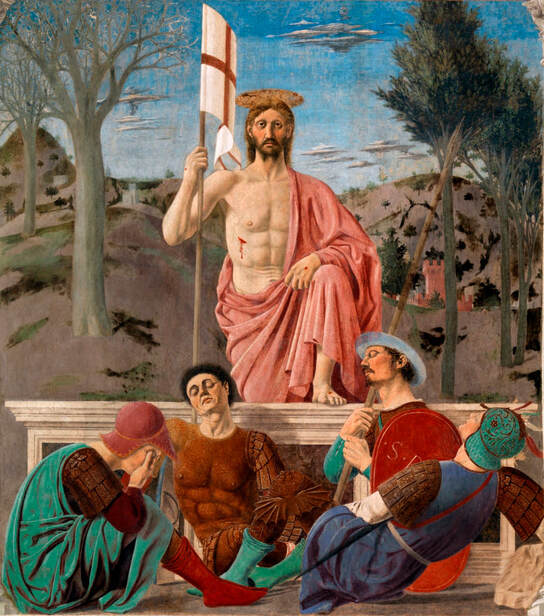

But besides the connection to Passover and Yom Kippur, Luther’s chorale refers to Christ’s lying “in the bonds of death”. The source of this image is the Gospels’ narration that after Jesus’s body was removed from the cross he was laid in a tomb; he was dead—“in the bonds of death”. This state is important within the progression of the chorale because it points to Jesus’s humanness and mortality and also lays the foundation for his great work of deliverance, which is the main topic of both the chorale and Bach’s cantata. One of the earliest creeds of the Christian church states that Jesus “was crucified, dead, and buried. He descended into Hell. On the third day he rose again from the dead….” Christian teaching holds that Death—the spiritual kind—is an inherent aspect of being human, emanating from humans’ departure from God, or “sin”; human power cannot overcome the effect of “sin” to bring us back to God. But Jesus, the pure one, in his physical death and in what we might understand as his time of dwelling in the place of decay and darkness, struggled with and overcame the great enemy, Death, to rise again. In so doing, he “killed” Death on behalf of all people, bringing everyone into God’s life and light forever. This, the basic concept of Easter, impels the believer to celebrate and exult with the joyous refrain, “Hallelujah”.

Commentary on Luther, Mühlhausen and the Chorale Text

Independent scholar David Brodsky of Cleveland has kindly provided an important insight into the context in which Luther wrote the chorale text. His commentary, which follows, enriches our understanding of the intensity of the text which Bach set nearly 200 years later.

“Mühlhausen in Thuringia, not far from Eisenach and Wittenberg, became the capital of a popular uprising, known as the Peasant War of 1525. The war encompassed many areas of Germany (Holy Roman Empire), today’s Austria, and Switzerland, and was the largest European popular rebellion before the French Revolution. The mass movement that erupted in armed conflict was based on long-standing commoners’ grievances and had produced several earlier rebellions. Luther initially sympathized with some of the movement’s demands. One of its leaders, whose headquarters was Mühlhausen, was Thomas Münzer, a Wittenberg-trained theologian who had been actively preaching rebellion for several years and cited Luther’s writings as authority. After war broke out in 1525, Luther sided with the propertied classes, condemning the mass movement and its leader and calling for the physical extermination of all rebels. 50,000 peasants were slaughtered at the battle of Frankenhausen alone in 1525, and total war casualties in Europe reached 100,000.

“It would be interesting to find out whether this history was known or alive in Mühlhausen over 180 years later when Bach wrote his Cantata No. 4, or whether Bach was familiar with it from other sources (e.g. his study of Luther). [Author’s note: the pursuit of these issues may well be pursued in the near future for another edition of this essay.] Luther’s chorale “Christ lag in Todesbanden” dates from 1524 and was included in a song collection published in Wittenberg the same year. Bach made a revised version of Cantata No. 4 in 1724, the 200th anniversary of Luther’s chorale on which the cantata is based, and one year before the 200th anniversary of the Peasant War. The modally-inflected (Luther) and bitonal (Luther and Bach) minor key of the melody, and Luther’s and Bach’s stress on suffering might refer to the stormy era of the chorale’s genesis, in which Luther’s career and life were at risk. Luther’s prominent imagery of war, death, blood, the strangler, bonds, captivity—aside from traditional religious meanings—evoke a state of war, the historical context in which the chorale was written. Both Luther’s generally upper-class religious and social movement and Münzer’s popular one made an appeal to the renewal of religion and its social consequences. The movement which Münzer led stressed in addition the liberation of commoners from feudal bondage. Renewal and freedom are messages of the Easter text of the chorale.”

[Author’s note: Renewal and freedom resonate with the Passover message as well.]

“It would be interesting to find out whether this history was known or alive in Mühlhausen over 180 years later when Bach wrote his Cantata No. 4, or whether Bach was familiar with it from other sources (e.g. his study of Luther). [Author’s note: the pursuit of these issues may well be pursued in the near future for another edition of this essay.] Luther’s chorale “Christ lag in Todesbanden” dates from 1524 and was included in a song collection published in Wittenberg the same year. Bach made a revised version of Cantata No. 4 in 1724, the 200th anniversary of Luther’s chorale on which the cantata is based, and one year before the 200th anniversary of the Peasant War. The modally-inflected (Luther) and bitonal (Luther and Bach) minor key of the melody, and Luther’s and Bach’s stress on suffering might refer to the stormy era of the chorale’s genesis, in which Luther’s career and life were at risk. Luther’s prominent imagery of war, death, blood, the strangler, bonds, captivity—aside from traditional religious meanings—evoke a state of war, the historical context in which the chorale was written. Both Luther’s generally upper-class religious and social movement and Münzer’s popular one made an appeal to the renewal of religion and its social consequences. The movement which Münzer led stressed in addition the liberation of commoners from feudal bondage. Renewal and freedom are messages of the Easter text of the chorale.”

[Author’s note: Renewal and freedom resonate with the Passover message as well.]

The Progression of Ideas in Luther’s Text Including An Alchemical Overlay

As has been noted, Luther wrote seven verses in this chorale. The number is important in several ways. It reflects the week-long feast of unleavened bread. It is symbolically a combination of three (the divine Trinity) and four (representing humanity). And, it replicates both the time of the biblical creation and alchemical symbolism. This last point requires some explanation.

Alchemy was a proto science generally regarded as a pseudo science or even black magic up to the time that the empirical scientific method was fully accepted in the late 18th century. Although based on misunderstood natural processes, it was a laboratory-based work that sought to promote healing (thus an early-stage apothecary science), and endeavored through a series of procedures to transmute base material into an imperishable substance, which would convey eternal life to whoever possessed it (thus an early stage of chemistry and metallurgy).

Alchemy was a proto science generally regarded as a pseudo science or even black magic up to the time that the empirical scientific method was fully accepted in the late 18th century. Although based on misunderstood natural processes, it was a laboratory-based work that sought to promote healing (thus an early-stage apothecary science), and endeavored through a series of procedures to transmute base material into an imperishable substance, which would convey eternal life to whoever possessed it (thus an early stage of chemistry and metallurgy).

These activities of a physical or concrete nature were seen to have parallels in the theological sphere, in which alchemy represented the process for attaining spiritual transformation (thus a mystical activity and early stage of psychology). The alchemical work employed a number of procedures, such as calcination or burning, dissolving, drying, blackening or decaying, and so on. The final stage of the process, at the point where the transmutation is actually effected, the material is said to become “red” or “gold”, and it will then be “projected” beyond itself in order to sustain others. In many of the alchemical treatises of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, these procedures were represented symbolically as events over the course of a week’s time, conveyed in seven events or stages. The uninitiated, ordinary reader would be thinking of a literal week’s events, but the alchemist would see in the “week” a series of procedures leading to the “Perfection” and “Projection” of the work.

Strange as it seems, Martin Luther was well aware of alchemy and its symbolism (although he is not known to actively engage in its work). When writing the text of “Christ lag in Todesbanden” he may well have interwoven allusions to the alchemical process when he created seven verses. We shall see some striking connections to the alchemical processes and the “week” of alchemical activity in the text.

Luther structured the seven verses of the chorale text symmetrically, using the fourth verse as the midpoint; the contents of verses on one side of the midpoint are mirrored in introversion on the other side, forming what is known as chiasm—a cross relationship. As we will see, Luther used this last feature as a way to show a spiritual meaning and set up connections between sets of theological ideas (see Herz’s lucid discussion of the chiasm in the Norton Critical Score).

Luther's melody originated in a sequence composed by Vipo of Burgundy in the early 11th century. Luther deviated from the model in Vipo’s sequence in an interesting way. Vipo began with a call to praise the paschal victim: “Victimae paschali laudes immolent Christiani” means “Let Christians dedicate praise to the paschal victim.” Luther, however, chose to begin his first verse with a specific vision of Christ already dead, “in the bonds of death”, having been crucified, “sacrificed”. Alchemically speaking, this is the base material, the “worst case scenario” which, through several procedures, will be turned into the imperishable “Perfection”, both within this verse and throughout the entire cantata.

This image of the already-dead Jesus that forms the first Stollen is answered in the second Stollen by the statement that Christ has risen and brings us life. Setting these opposite concepts to the same music in the same part of the music’s Bar form provides the central theological double whammy that this chorale is all about: the Passover victim is sacrificed, and its death is the means by which life is made possible. The response, in the Abgesang, is joy, praise, thanksgiving to God. Verse one, then, is both the deliverance story in a nutshell and a microcosm of the remainder of the chorale. The following summary of each of the remaining verses will give an idea of how the story progresses. There will be more detail in the next section as a part of the discussion of the musical setting of the entire cantata. (Once again, Gerhard Herz provides another set of insights in the Norton Critical Score.)

Luther structured the seven verses of the chorale text symmetrically, using the fourth verse as the midpoint; the contents of verses on one side of the midpoint are mirrored in introversion on the other side, forming what is known as chiasm—a cross relationship. As we will see, Luther used this last feature as a way to show a spiritual meaning and set up connections between sets of theological ideas (see Herz’s lucid discussion of the chiasm in the Norton Critical Score).

Luther's melody originated in a sequence composed by Vipo of Burgundy in the early 11th century. Luther deviated from the model in Vipo’s sequence in an interesting way. Vipo began with a call to praise the paschal victim: “Victimae paschali laudes immolent Christiani” means “Let Christians dedicate praise to the paschal victim.” Luther, however, chose to begin his first verse with a specific vision of Christ already dead, “in the bonds of death”, having been crucified, “sacrificed”. Alchemically speaking, this is the base material, the “worst case scenario” which, through several procedures, will be turned into the imperishable “Perfection”, both within this verse and throughout the entire cantata.

This image of the already-dead Jesus that forms the first Stollen is answered in the second Stollen by the statement that Christ has risen and brings us life. Setting these opposite concepts to the same music in the same part of the music’s Bar form provides the central theological double whammy that this chorale is all about: the Passover victim is sacrificed, and its death is the means by which life is made possible. The response, in the Abgesang, is joy, praise, thanksgiving to God. Verse one, then, is both the deliverance story in a nutshell and a microcosm of the remainder of the chorale. The following summary of each of the remaining verses will give an idea of how the story progresses. There will be more detail in the next section as a part of the discussion of the musical setting of the entire cantata. (Once again, Gerhard Herz provides another set of insights in the Norton Critical Score.)

|

Verse two is devoted to describing the power of Death.

The text is dark, full of despair and hopelessness as the universal human condition is revealed in its devastating sin and impotence. In alchemical terms, this might be considered a “blackened” stage. Verse three tells of the coming of Jesus to undergo Death as a substitute for our having to do so (a connection to the sacrificial lamb of Yom Kippur), and reminds us that all that remains of Death is a powerless image. Verse four, the center and pivot point of the cantata, is also at the crux of Christian theology. It describes the battle between Life and Death and the ultimate defeat of Death. Verse five is the correlative of Verse three. It reveals the Easter Lamb “roasted in fervent love”—an allusion to the victim which feeds the believers, becoming the Passover meal and the Christian sacrament of communion. The mark of the blood on the door is held up against Death, and those under its protection cannot be harmed. The “roasting” suggests the calcination stage of the alchemical work. Verse six corresponds with Verse two by its opposition. It is bathed in light and life; the work of deliverance from Death has been achieved. Alchemically, here we have achieved the “Perfection”, the complete transmutation of the base material into imperishable “Gold”. Verse seven shows the alchemical “Projection”, a continuation of the Believer’s life after deliverance from Death. The Christian prospers (eats well, lives well) on the life-giving food of the (Christian) Passover bread (in Christian communion, the bread is Christ’s body—the Paschal Lamb—with the paradoxical, simultaneous symbol of the Passover bread). We are reminded that the old leaven, the yeast from the previous batch of sourdough, the old way of life, will not be present because the new grace, life as a delivered people, supplants it. Our souls will be sustained only by the new food, Christ (the Paschal Lamb, the bread of life). This verse not only sums up the story that was projected in verse one but projects a continuity of being, an on-goingness that leads beyond the experience of the chorale itself and into the world, transformed by the passage into life, secure in spiritual immortality. This is the verse that the congregation would join in singing, further projecting the message beyond the cantata into the lives of the faithful. |

III. HEARING BACH’S MUSIC FOR CANTATA 4

In this section of the essay I want to share some observations on the remarkable way in which Bach makes the chorale text live through music by looking at each movement in order. However, because part or all of the melody of the chorale “Christ lag in Todesbanden” is present in some way in each and every movement of Bach’s Cantata 4, it is very important for the listener to be familiar with that tune. The Lutheran congregation in Bach’s churches would already have known this hymn and may even have joined in singing Verse Seven at the end of the cantata. Today, this great work is performed for a very diverse public not steeped in Lutheran tradition. I recommend, therefore, that everyone review the chorale melody by listening first to the seventh verse, where the melody is presented clearly in the soprano; perhaps even do this several times to become really acquainted with that special melody. Then, hearing the cantata through from the beginning, the listener will likely become aware of more nuances of the way Bach conveys the meaning of the text through the music.

|

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Seven Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director |

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Sinfonia (Instrumental)

The opening Sinfonia poignantly suggests dark and sorrowful things: mankind’s dire straits before deliverance, the horrendous suffering of one executed by crucifixion, the desolation of those looking on at the crucifixion, the grief of those who removed Jesus’s body from the cross and buried him. On a personal note, although I had sung this cantata many times years ago as a college student, I never perceived the Sinfonia at that time to be other than an abstract reminder of the opening of the chorale melody. Now, however, I think perhaps Bach was using it to set the stage for us—taking us, maybe as actual observers, to the crucifixion, the deposition from the cross, perhaps even Jesus’ burial. In this brief instrumental introduction, Bach surely reaches out to us and attempts to move us with passionate music.

How does Bach achieve this amazing summary?

As the Sinfonia begins, the chorale melody is broken into small figures comprised of the first descending half step, a heavy sigh motive. (This motive will become further important in Verse Two of the cantata, where we will find a possible interpretation of it.) After each figure is a response in the same rhythm but at a lower range, with the sigh echoed in an inner voice and inverted in the bass. To me, the effect is as if an outward cry is echoed from within by the heart’s own cry of woe. Eventually, the sighing motif extends into the first musical phrase of the chorale, modified to lead to a contrasting phrase. The new phrase begins as if it will repeat the opening sigh, but instead drops with a sense of heaviness. The dropping pattern gives way to a series of more active rising figures. These culminate in a surprising cruciform solo in the first violins, beginning on f-natural and dropping to e’’, then leaping up to c’’’, then dropping to a’’ and f-natural, then crossing up to a’’ again, and finally crossing over the f-natural to descend to d#’’. This solo moment ends in an unusual melodic drop from a high F# down to a G, a major seventh below. Normally the resolution from F# would be up to G, a half step higher, but Bach created an aural hiatus here. The final cadence descends even further from the twisted resolution.

This is a bizarre moment indeed, but there is symbolic logic in the gesture: Bach has, in the last five measures of this short Sinfonia, shown us the elevation of the victim to the cross, the loneliness of his death agony, his deposition from the cross, and even his being set into a resting place—a burial. The final chord is not minor but major, a “Picardy third”, which is surprisingly peaceful. Whether the peace is the repose of death or a glimpse of hopefulness may become clear later.

How does Bach achieve this amazing summary?

As the Sinfonia begins, the chorale melody is broken into small figures comprised of the first descending half step, a heavy sigh motive. (This motive will become further important in Verse Two of the cantata, where we will find a possible interpretation of it.) After each figure is a response in the same rhythm but at a lower range, with the sigh echoed in an inner voice and inverted in the bass. To me, the effect is as if an outward cry is echoed from within by the heart’s own cry of woe. Eventually, the sighing motif extends into the first musical phrase of the chorale, modified to lead to a contrasting phrase. The new phrase begins as if it will repeat the opening sigh, but instead drops with a sense of heaviness. The dropping pattern gives way to a series of more active rising figures. These culminate in a surprising cruciform solo in the first violins, beginning on f-natural and dropping to e’’, then leaping up to c’’’, then dropping to a’’ and f-natural, then crossing up to a’’ again, and finally crossing over the f-natural to descend to d#’’. This solo moment ends in an unusual melodic drop from a high F# down to a G, a major seventh below. Normally the resolution from F# would be up to G, a half step higher, but Bach created an aural hiatus here. The final cadence descends even further from the twisted resolution.

This is a bizarre moment indeed, but there is symbolic logic in the gesture: Bach has, in the last five measures of this short Sinfonia, shown us the elevation of the victim to the cross, the loneliness of his death agony, his deposition from the cross, and even his being set into a resting place—a burial. The final chord is not minor but major, a “Picardy third”, which is surprisingly peaceful. Whether the peace is the repose of death or a glimpse of hopefulness may become clear later.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Sinfonia

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Sinfonia

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse One

Verse One

(SATB chorus, violins I and II, violas I and II, continuo)

(SATB chorus, violins I and II, violas I and II, continuo)

Christ lag in Todesbanden, für unsre Sünd gegeben.

Er ist wieder erstanden und hat uns bracht das Leben.

Des wir sollen fröhlich sein, Gott loben und ihm dankbar sein

und singen Hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Christ lay in Death’s bonds, given for our sins.

He has risen again and has brought us life.

So we shall be joyful, praise God and be thankful to him,

and sing hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Er ist wieder erstanden und hat uns bracht das Leben.

Des wir sollen fröhlich sein, Gott loben und ihm dankbar sein

und singen Hallelujah. Hallelujah!

Christ lay in Death’s bonds, given for our sins.

He has risen again and has brought us life.

So we shall be joyful, praise God and be thankful to him,

and sing hallelujah. Hallelujah!

The interpretation of the Sinfonia that begins this cantata may seem farfetched when we look at it as an isolated movement. However, the Sinfonia is not truly isolated. It must be perceived as a kind of prolog, contextually linked to what follows immediately, which is the first chorale verse. Bach opens this verse with a single sound: the sopranos’ first note and word of the chorale. This first unwavering vocal note has only a skeletal bass line against it and seems interminable. The remaining voices enter one by one after a beat and a half, and the strings enter after an entire measure; the sopranos still hold the first note even through the second measure as well before going on with the next note of the melody!

In a way, the sopranos’ augmentation (lengthening) of the choral melody’s notes suggests a lethargy, a stupor that reminds us of lifelessness. Yet, the melody’s lifelessness is not the whole story. As the verse progresses to the second Stollen and the text mentions the words “arisen” and “life”, and the soprano continues its stupefied augmentation, the other voices and instruments become increasingly active. On the world Leben (“life”) the lower three voices are rhythmically much more active. The entire Abgesang text refers to the joy with which we praise God for deliverance, and here sixteenth notes abound in all voices. Herz calls the musical setting of the word fröhlich (joyful) “garlands of joy” (p. 91). Finally, the sopranos leave their augmentation, and the word of rejoicing, “hallelujah”, is presented at a fast tempo marked Alla breve. We have been shown the return to life in the music.

In a way, the sopranos’ augmentation (lengthening) of the choral melody’s notes suggests a lethargy, a stupor that reminds us of lifelessness. Yet, the melody’s lifelessness is not the whole story. As the verse progresses to the second Stollen and the text mentions the words “arisen” and “life”, and the soprano continues its stupefied augmentation, the other voices and instruments become increasingly active. On the world Leben (“life”) the lower three voices are rhythmically much more active. The entire Abgesang text refers to the joy with which we praise God for deliverance, and here sixteenth notes abound in all voices. Herz calls the musical setting of the word fröhlich (joyful) “garlands of joy” (p. 91). Finally, the sopranos leave their augmentation, and the word of rejoicing, “hallelujah”, is presented at a fast tempo marked Alla breve. We have been shown the return to life in the music.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse One

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse One

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Two

Verse Two

(Soprano doubled by cornetto, Alto doubled by tenor trombone, and continuo)

(Soprano doubled by cornetto, Alto doubled by tenor trombone, and continuo)

Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt bei allen Menschenkindern,

Das macht’ alles unsre Sünd, kein Unschuld war zu finden.

Davon kam der Tod so bald und nahm über uns Gewalt, hielt uns

in seinem Reich gefangen. Hallelujah!

Among all the children of mortals, no one could conquer Death;

Our sin did all this; there was no innocence to be found.

Therefore Death came so suddenly and took power over us,

held us captive in his kingdom. Hallelujah!

Das macht’ alles unsre Sünd, kein Unschuld war zu finden.

Davon kam der Tod so bald und nahm über uns Gewalt, hielt uns

in seinem Reich gefangen. Hallelujah!

Among all the children of mortals, no one could conquer Death;

Our sin did all this; there was no innocence to be found.

Therefore Death came so suddenly and took power over us,

held us captive in his kingdom. Hallelujah!

If Bach were a jazz musician he might have invented “stride” piano style. In this verse the continuo has a marvelous walking bass which stalks so inexorably that it must be Bach’s analogy to Death. Over this, the soprano and alto (whether solos or sections of voices) writhe and clash in a description of sin. They often engage in tight dissonances. The struggle to remember the chorale tune: at the beginning it’s broken into small figures like those in the Sinfonia, and elsewhere it is stretched out of shape. The brokenness of the human soul is thus clearly exemplified. The two voice parts are disjunct, beginning separately, then interweaving, and matching only at the ends of phrases. The voices try to break free but can’t. Even the Hallelujah is in chains (of suspensions). Herz’s discussion of the movement in the Norton Critical Score, 94ff, is vivid and insightful, but too long to quote here. It is definitely recommended reading.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Two

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Two

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Three

Verse Three

(Tenor, violins I and II, continuo)

(Tenor, violins I and II, continuo)

Jesus Christus, Gottes Sohn, an unser Statt ist kommen,

Und hat die Sünde weggetan, damit dem Tod genommen

All sein Recht und sein Gewalt, da bleibet nichts denn Tods Gestalt,

den Stachl hat er verloren. Hallelujah!

Jesus Christ, God’s son, has come in our place

And done away with sins, and with that took away

All Death’s rights and its power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image,

Death has lost its thorn. Hallelujah!

Und hat die Sünde weggetan, damit dem Tod genommen

All sein Recht und sein Gewalt, da bleibet nichts denn Tods Gestalt,

den Stachl hat er verloren. Hallelujah!

Jesus Christ, God’s son, has come in our place

And done away with sins, and with that took away

All Death’s rights and its power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image,

Death has lost its thorn. Hallelujah!

The brilliant violin solo that begins the third verse suggests the confident vigor of a hero such as those in the old classic adventure movies, coming to save the damsel in distress. Bach’s choice of the bright tenor voice to sing the chorale verse encourages us to imagine a parallel to operatic high male voices performing the role of the grand hero. The combination of swashbuckling violin (an instrument on which Bach was a master) and bold tenor voice suggests the heroic nature of the savior; we seem to have entered a kind of sacred mini-opera here. The driving violin melody line is almost incessant throughout the movement, while the tenor’s half lines are separated with brief interruption.

A marvelous change in the texture and pace occurs at the third line of the text, in which we learn that Death has lost all its “rights and power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image”. As the tenor begins singing this text, the violin actually comes to a halt in a double-stopped unison with both the tenor note and the continuo bass. Then, as both voice and continuo forge ahead, the violin drops out entirely for a beat. This brief hiatus in the pattern marks the beginning of the passage that gives a new understanding of Death. The violin resumes its activity again for a very short passage. Then, at the end of the word “power” (Gewalt) it changes from its energetic sixteenth-note cascade to hammer-like double-, triple-, and quadruple-stop chords. At the same time, the continuo bass takes over the sixteenth-note pattern, driving downward through a breathtaking octave and a half. Meanwhile, the tenor has just completed the phrase “da bleibet nichts” –“so nothing remains”. In this very moment there is a space of silence—nothing—in the music.

Then, another surprise: an Adagio marking while the tenor sings the rest of the phrase, “denn Tods Gestalt” –“than Death’s image”. The word Tods is held out while the violin provides a cruciform descant above (b’ up to d’’, crossing down to a#’ and back to b’), and then the tenor echoes it as an ornament to finish the word. With the cessation of activity in the Adagio passage, the power of Death has insinuated itself into the movement, but with its energy much drained. At the last syllable of “Gestalt” (“image”) the tempo changes again to Allegro and the violin resumes its virtuoso activity at the marked forte dynamic. Life returns to the music, joyfully reminding that Death has lost its thorn or sting. The Hallelujahs are vivacious and ornate in violin, voice, and continuo, as if our swashbuckling hero is merrily outduelling his fearsome opponent.

A marvelous change in the texture and pace occurs at the third line of the text, in which we learn that Death has lost all its “rights and power; so nothing remains other than Death’s image”. As the tenor begins singing this text, the violin actually comes to a halt in a double-stopped unison with both the tenor note and the continuo bass. Then, as both voice and continuo forge ahead, the violin drops out entirely for a beat. This brief hiatus in the pattern marks the beginning of the passage that gives a new understanding of Death. The violin resumes its activity again for a very short passage. Then, at the end of the word “power” (Gewalt) it changes from its energetic sixteenth-note cascade to hammer-like double-, triple-, and quadruple-stop chords. At the same time, the continuo bass takes over the sixteenth-note pattern, driving downward through a breathtaking octave and a half. Meanwhile, the tenor has just completed the phrase “da bleibet nichts” –“so nothing remains”. In this very moment there is a space of silence—nothing—in the music.

Then, another surprise: an Adagio marking while the tenor sings the rest of the phrase, “denn Tods Gestalt” –“than Death’s image”. The word Tods is held out while the violin provides a cruciform descant above (b’ up to d’’, crossing down to a#’ and back to b’), and then the tenor echoes it as an ornament to finish the word. With the cessation of activity in the Adagio passage, the power of Death has insinuated itself into the movement, but with its energy much drained. At the last syllable of “Gestalt” (“image”) the tempo changes again to Allegro and the violin resumes its virtuoso activity at the marked forte dynamic. Life returns to the music, joyfully reminding that Death has lost its thorn or sting. The Hallelujahs are vivacious and ornate in violin, voice, and continuo, as if our swashbuckling hero is merrily outduelling his fearsome opponent.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Three

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Three

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Four

Verse Four

(SATB chorus and continuo)

(SATB chorus and continuo)

Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg, da Tod und Leben rungen,

Das Leben behielt den Sieg, es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündiget das, wie ein Tod den andern frass,

ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden. Hallelujah!

It was an astonishing war, when Death and Life struggled.

Life secured the victory, it has swallowed up Death.

Scripture had proclaimed this, how one Death gobbled up another,

A mockery has been made of Death. Hallelujah!

Das Leben behielt den Sieg, es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündiget das, wie ein Tod den andern frass,

ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden. Hallelujah!

It was an astonishing war, when Death and Life struggled.

Life secured the victory, it has swallowed up Death.

Scripture had proclaimed this, how one Death gobbled up another,

A mockery has been made of Death. Hallelujah!

The central fourth verse is the great battle between Death and Life, cast as a fugal chorale prelude or a chorale fantasy. In the midst of the fray the great chorale melody holds constant in longer notes in the alto part, a kind of internal anchor. The settings of both Stollen are identical in this verse. In the Abgesang, however, Bach includes some vivid word painting. At the passage “ein Tod den andern frass”—“one Death gobbled up another”—he has the voices in canon literally bringing an end to themselves, like an early 18th-century Pac Man. Incidently, the German word frass is used when non-humans eat, so the translation as “gobble up” is apt. In the next phrase, “ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden”—“a mockery has been made of Death”—Bach has all the voices hurl ridicule (Spott) at Death. The Hallelujah passage appears to sit down gradually, looking in all directions first so as to be assured that all is in order; it comes to rest by approaching the cadence not once but twice. The Picardy third which makes the final chord major seems to be an ultimate statement of satisfaction at the great victory.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Four

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Four

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Five

Verse Five

(Bass, violins I and II, violas I and II, continuo)

(Bass, violins I and II, violas I and II, continuo)

Hier ist das rechte Osterlamm, davon Gott hat geboten,

Das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm in heisser Lieb gebraten,

Das Blut zeichnet unsre Tür, das halt der Glaub dem Tode für,

der Würger kann uns nicht mehr schaden. Hallelujah!

Here is the true Easter lamb that God has presented,

That is roasted in ardent love high on the trunk of the cross.

The blood marks our door, faith holds it up against Death.

The Destroyer can harm us no more. Hallelujah!

Das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm in heisser Lieb gebraten,

Das Blut zeichnet unsre Tür, das halt der Glaub dem Tode für,

der Würger kann uns nicht mehr schaden. Hallelujah!

Here is the true Easter lamb that God has presented,

That is roasted in ardent love high on the trunk of the cross.

The blood marks our door, faith holds it up against Death.

The Destroyer can harm us no more. Hallelujah!

As we pass the remarkable center of the cantata, the fourth-movement fulcrum of the cross-form Bach employed, we find reference to earlier movements. Verse five as a bass solo balances the tenor solo of Verse three. But here Bach introduces a number of other symbols to call to mind the Paschal lamb and the feast of Passover. First of all, the triple meter and great solemnity of the movement have a parallel in the processional opening of the much later Cantata 140, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, in which the heavenly bridegroom approaches another kind of solemn and sacred feast—a wedding. The triple meter is one way in which Bach refers to Christ or the Trinity in his music. Second, as Gerhard Herz points out (p. 106), the continuo bass begins with a special descending chromatic line: it is a traditional opening for a passacaglia, especially one related to sorrow and death, such as Dido’s lament in Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas (1689). In particular, Bach used it in the Crucifixus of his B-minor Mass during his Leipzig years. In this cantata, the descending continuo passage begins each of the Stollen and the Abgesang; its triple application in this verse is a further reference to Christ as this verse dwells on his sacrificial death.

A few passages of word painting are noteworthy. While singing the word “Kreuz”—“cross”—in the second Stollen, the bass presents the cruciform melody (b, c#’, a#, c#’, b) that will appear so often in Bach’s other sacred works, notably the St. Matthew Passion. An echo of the “cross” occurs in the first violin part when the bass sings of “heisser Lieb”—“ardent love”, suggesting the immense love of Christ in giving himself to death for humanity on the cross. Herz calls attention to the fact that Bach fully harmonized the second Stollen with the use of the four string parts, thereby giving this text a richness and warmth that reflects the meaning of the words (p. 107). In the Abgesang, Bach incorporates a marvelous image of Death by placing it for the singer on a horrendously low pitch approached by a “killer” leap, in itself deadly, for it is an octave-displaced descending tritone (the “devil in music”). Finally, in the next phrase only a few measures later, Bach places the word “Würger”—“destroyer”—at the high end of the singers’s range, and held out for four measures. And you thought Bach had no sense of humor! By the way, Herz translates “Würger” as “strangler”, which certainly could apply to this music if the singer isn’t careful.

A few passages of word painting are noteworthy. While singing the word “Kreuz”—“cross”—in the second Stollen, the bass presents the cruciform melody (b, c#’, a#, c#’, b) that will appear so often in Bach’s other sacred works, notably the St. Matthew Passion. An echo of the “cross” occurs in the first violin part when the bass sings of “heisser Lieb”—“ardent love”, suggesting the immense love of Christ in giving himself to death for humanity on the cross. Herz calls attention to the fact that Bach fully harmonized the second Stollen with the use of the four string parts, thereby giving this text a richness and warmth that reflects the meaning of the words (p. 107). In the Abgesang, Bach incorporates a marvelous image of Death by placing it for the singer on a horrendously low pitch approached by a “killer” leap, in itself deadly, for it is an octave-displaced descending tritone (the “devil in music”). Finally, in the next phrase only a few measures later, Bach places the word “Würger”—“destroyer”—at the high end of the singers’s range, and held out for four measures. And you thought Bach had no sense of humor! By the way, Herz translates “Würger” as “strangler”, which certainly could apply to this music if the singer isn’t careful.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Five

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Five

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Six

Verse Six

(Soprano, Tenor and continuo)

(Soprano, Tenor and continuo)

So feiern wir das hohe Fest mit Herzensfreud und Wonne,

Das uns der Herre [er]scheinen lässt, er ist selber die Sonne,

Der durch seiner Gnade Glanz erleuchtet unsre Herzen ganz,

Der Sünden Nacht ist verschwunden. Hallelujah!

So we celebrate the high feast with joyful heart and ecstasy,

The Lord makes it present to us, he himself is the sun,

Who through the radiance of his grace completely illumines our hearts.

The night of sin has disappeared. Hallelujah!

Das uns der Herre [er]scheinen lässt, er ist selber die Sonne,

Der durch seiner Gnade Glanz erleuchtet unsre Herzen ganz,

Der Sünden Nacht ist verschwunden. Hallelujah!

So we celebrate the high feast with joyful heart and ecstasy,

The Lord makes it present to us, he himself is the sun,

Who through the radiance of his grace completely illumines our hearts.

The night of sin has disappeared. Hallelujah!

Verse Six balances Verse Two and simultaneously is an inversion of its message. Verse Two is dark and dwells on the “night of sin”. Here in Verse Six all is light; the work of deliverance has been achieved. The believer celebrates the holy feast (the Eucharist, the Christian interpretation of the Passover) with great joyfulness, basking in the light of the Lord. Its duet mirrors the duet of Verse Two, even to the use of only continuo in company with voices. However, in Verse Six the bright quality of the tenor voice brings a new quality to the duet, whereas the earlier duet had a more somber timbre of the alto paired with soprano. The bright soprano and tenor voices chosen to present the text suggest the brilliance of the Sun which is the Lord, illuminating the hearts of those at the feast.

There is a dancing quality to the movement in keeping with the celebratory text, yet the dotted rhythm of the continuo bass, and eventually the triplet division of the beats in the two voices, point to a sacred, even royal ambiance. The voices in Verse Two were forever at each others’ throats, harmonically and rhythmically speaking, but here in Verse Six the sweet harmonies seem like floral garlands as they decorate the text with their long, synchronized melismas. The gracious motion of rhythm and melody and the harmonic beauty suggest an extraordinary event, splendor, rapture, and surprisingly, serenity.

There is a dancing quality to the movement in keeping with the celebratory text, yet the dotted rhythm of the continuo bass, and eventually the triplet division of the beats in the two voices, point to a sacred, even royal ambiance. The voices in Verse Two were forever at each others’ throats, harmonically and rhythmically speaking, but here in Verse Six the sweet harmonies seem like floral garlands as they decorate the text with their long, synchronized melismas. The gracious motion of rhythm and melody and the harmonic beauty suggest an extraordinary event, splendor, rapture, and surprisingly, serenity.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Six

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Six

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata - Verse Seven

Verse Seven

(Soprano doubled by violins I and II and cornetto, Alto doubled by viola I and Trombone I, Tenor doubled by viola II and Trombone II, Bass doubled by trombone III, and continuo)

(Soprano doubled by violins I and II and cornetto, Alto doubled by viola I and Trombone I, Tenor doubled by viola II and Trombone II, Bass doubled by trombone III, and continuo)

Wir essen und leben wohl in rechten Osterfladen,

Der alte Sauerteig nicht soll sein bei dem Wort der Gnaden,

Christus will die Koste sein und speisen die Seele allein,

der Glaub will keins andern leben. Hallelujah.

We eat and live well on the true Passover bread.

The old leaven shall not exist beside the word of grace;

Christ will be the food and alone feed the soul,

Faith will live by no other. Hallelujah!

Der alte Sauerteig nicht soll sein bei dem Wort der Gnaden,

Christus will die Koste sein und speisen die Seele allein,

der Glaub will keins andern leben. Hallelujah.

We eat and live well on the true Passover bread.

The old leaven shall not exist beside the word of grace;

Christ will be the food and alone feed the soul,

Faith will live by no other. Hallelujah!

The seventh verse is a four-voice setting of the chorale melody. Here, more than in any preceding verse, major chords mark cadences at the midpoints of text phrases, and the harmonic movement includes sections in major keys (if temporarily). The final major chord affirms the brighter harmonic setting.

In its simplicity, this concluding verse brings the chorale to the people, the congregation, opening it up to the participation of ordinary men and women. In a sense, Bach parallels the life-giving properties of participation in the Eucharist, which sustains the faithful and brings spiritual “good living” to those who eat and drink the special food, by having the congregation participate in singing the chorale. In Alchemy, this represents the “projection”, the extension of the perfected material to the world at large. Symbolically, the spiritual life of the congregation has been nourished in this music.

In its simplicity, this concluding verse brings the chorale to the people, the congregation, opening it up to the participation of ordinary men and women. In a sense, Bach parallels the life-giving properties of participation in the Eucharist, which sustains the faithful and brings spiritual “good living” to those who eat and drink the special food, by having the congregation participate in singing the chorale. In Alchemy, this represents the “projection”, the extension of the perfected material to the world at large. Symbolically, the spiritual life of the congregation has been nourished in this music.

Bach's "Christ lag in Todesbanden", BWV 4 Cantata

Verse Seven

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Verse Seven

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman, director

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.