- Home

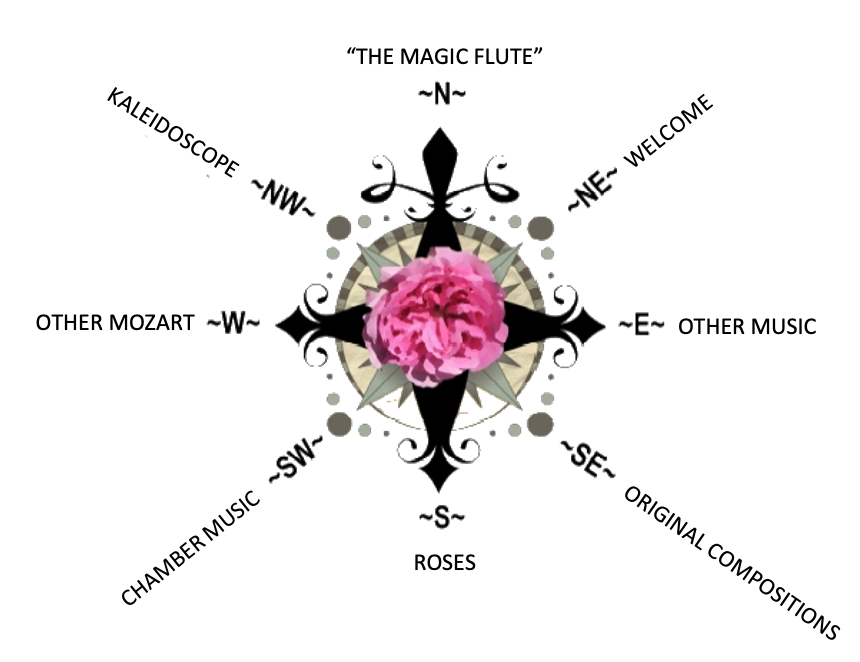

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

POULENC: GLORIA

by Judith Eckelmeyer

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) was born and raised in Paris. He learned piano as a child from his mother, and was introduced through her and her brother into a highly secular world of contemporary French literature and music. Poulenc’s father, whom he described as a “deeply religious but liberal” Catholic from the south of France, died in 1917, after which Francis moved in the spheres of his mother’s secular, cosmopolitan world.

As a teen, he studied the piano music of Debussy and Ravel, then met Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud—three of Les Six—and Eric Satie, their older friend and guide to the avant-garde. At the age of 18 he dedicated his first published work to Satie and became associated with the iconoclastic Six. Although he eventually studied composition formally, it was with private teachers rather than in a classically structured program; he famously progressed no further in counterpoint than Bach’s chorales in spite of having met and conversed with Schoenberg and his pupils in 1921 in Vienna. In this highly individualistic and open-ended development, Poulenc acquired the diversity of resources that would characterize his music: sensitivity to harmonic and tonal color, melodic freedom, and the “language” of popular music current in Parisian cafes and theaters.

Poulenc’s world changed in 1936 when his friend, composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud, was killed in a car accident. In the wake of this tragedy Poulenc retired to Rocamadour, a pilgrimage town in the southern region from which his father had come. There, Poulenc returned to religious faith. His very first sacred choral piece, “Litanies to the Black Virgin” of 1936, is a setting for women’s and children’s voices of recitations honoring the Virgin who is represented by a blackened wood statue in the church of Notre Dame in Rocamadour. Other sacred choral works followed soon after and appear throughout the rest of his life.

One such work was his 1969 setting of the Gloria, one of the portions of the liturgy of the Mass, creating with it a concert work of 6 exceedingly varied atmospheres, not all of which seem to connect directly with the text being set in the particular movement. The full text, and Poulenc’s division of it, are as follows:

1. Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to men of good will.

Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth to men of good will.

2. Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

We praise Thee, we bless Thee, we adore Thee, we glorify Thee.

We give Thee thanks for Thy great glory.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

We praise Thee, we bless Thee, we adore Thee, we glorify Thee.

We give Thee thanks for Thy great glory.

3. Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father omnipotent.

Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father omnipotent.

4. Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe.

Lord, the only begotten son, Jesus Christ.

Lord, the only begotten son, Jesus Christ.

5. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris, Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostrum.

Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father,

Who bears the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

Who bears the sins of the world, receive our prayer.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostrum.

Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father,

Who bears the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

Who bears the sins of the world, receive our prayer.

6. Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus sanctus. Tu solus Dominus. Tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.

Cum Sancto Spiritu, in Gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us.

For You alone are holy, You alone are the Lord, You alone are the highest, Jesus Christ.

With the Holy Spirit, in the Glory of God the Father. Amen.

Quoniam tu solus sanctus. Tu solus Dominus. Tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.

Cum Sancto Spiritu, in Gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us.

For You alone are holy, You alone are the Lord, You alone are the highest, Jesus Christ.

With the Holy Spirit, in the Glory of God the Father. Amen.

As we know, dissonance comes in many flavors, from intensely bitter, to harsh, to melancholy, to poignantly sweet. He was a master at choosing just the right combination of pitches to help define the emotional values of the texts, and he also intensified the choral effects through the vocal ranges. The musical styles in the Gloria range from the realm of mysticism to the secular jollity of the dances of the Folies Bergère. He felt no obligation to follow the traditional accents of ecclesiastical Latin, but introduced what seem to be the speech patterns of the every-day French citizen. A good example is at the word “benedicimus” (in no. 2), with the accent not on the expected syllable -di- but rather on -mus-: “benediciMUS te”.

Poulenc thought his sacred choral music represented “the best and most genuine part” of himself; indeed, all of the harmonic and textural attributes in this work reflect his absolute dedication to reaching into the depths of texts. In the Gloria, the result is in turn meditative, joyful, exuberant, and mystical.

Poulenc thought his sacred choral music represented “the best and most genuine part” of himself; indeed, all of the harmonic and textural attributes in this work reflect his absolute dedication to reaching into the depths of texts. In the Gloria, the result is in turn meditative, joyful, exuberant, and mystical.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2021

Poulenc's Gloria

(Premier performance with Poulenc in attendance)

Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra & Chorus Pro Musica

Adele Addison, soprano

(Premier performance with Poulenc in attendance)

Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra & Chorus Pro Musica

Adele Addison, soprano

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.