- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

CONCERTO

Origins and Flourishing of the Concerto in the Baroque

By Judith Eckelmeyer

The meaning of the term “concerto” is either an argument, or, an agreement! Both meanings underlie the earliest uses of the term in the very late years of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century in Italy—around the beginning of the Baroque era in music.

Even the earliest works called “concerto” feature a combination of forces—different instruments, or instruments and voices—which can work together or in contrast with each other. A synonymous term at this early stage was “sinfonia”, which indicated that diverse instruments were “working together” or “sounding together”. Additionally, the term “concertante” meant something very similar: works involving contrasting or diverse sound sources, such as instrument and voice, and especially a vocal work with instrumental accompaniment.

It is often disconcerting to find the plural of the Italian term “concerto” given as “concerti” instead of “concertos”. Either term is acceptable. “Concertos” seems more normal in today’s world, but it gets awkward when talking about more than one “concerto grosso” (see below). These would properly be “concerti grossi” in Italian, not concertos grosso” (a plural concerto, singular grosso). So, in the following discussion, uncomplicated concertos will be used, but concerti grossi will also be used! We live in a complex world.

Even the earliest works called “concerto” feature a combination of forces—different instruments, or instruments and voices—which can work together or in contrast with each other. A synonymous term at this early stage was “sinfonia”, which indicated that diverse instruments were “working together” or “sounding together”. Additionally, the term “concertante” meant something very similar: works involving contrasting or diverse sound sources, such as instrument and voice, and especially a vocal work with instrumental accompaniment.

It is often disconcerting to find the plural of the Italian term “concerto” given as “concerti” instead of “concertos”. Either term is acceptable. “Concertos” seems more normal in today’s world, but it gets awkward when talking about more than one “concerto grosso” (see below). These would properly be “concerti grossi” in Italian, not concertos grosso” (a plural concerto, singular grosso). So, in the following discussion, uncomplicated concertos will be used, but concerti grossi will also be used! We live in a complex world.

Instruments:

Early Baroque instrumental compositions were most often for violins and continuo—violins because of their capacity for correct tuning in any key. The violin of the time looks very much like a modern violin, with four strings made of gut; the sound is less bright and softer in volume than with modern steel strings. The bridge is less arched than that of the modern violin, allowing the player to execute chords by multiple stopping. The fingerboard is slightly shorter, as the general range of pitches was less extreme than in modern works. The bow is convex (curved outward).

Early Baroque instrumental compositions were most often for violins and continuo—violins because of their capacity for correct tuning in any key. The violin of the time looks very much like a modern violin, with four strings made of gut; the sound is less bright and softer in volume than with modern steel strings. The bridge is less arched than that of the modern violin, allowing the player to execute chords by multiple stopping. The fingerboard is slightly shorter, as the general range of pitches was less extreme than in modern works. The bow is convex (curved outward).

Violinist Lisa Grodin discusses the differences between the baroque violin and the modern violin.

The harmony-producing instrument in the continuo for secular works was usually a harpsichord, but it could be a chord-producing instrument such as lute or theorbo instead; for church works the typical instrument was organ. The theorbo is a large bass lute invented probably at the end of the 16th century in Venice or nearby Padua; they are about five feet long and have 8 strings associated with the fretted fingerboard and additional strings set beside the fingerboard. The additional strings were tuned on a different pegbox from those on the fingerboard, and could be plucked at their tuned pitch or resonate sympathetically.

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Lutenist, Elizabeth Kenny

Baroque Theorbo

Baroque Theorbo

An even larger version of the theorbo was the chitarrone, and larger than a chitrrone was the angelica, having 16 or 17 strings. In sacred works, produced for use in the church, the organ provided the harmonic foundation.

Marin Marais - Le Badinage, Maria Wilgos - chitarrone

The continuo needed a low string instrument to reinforce the bass line. Typically a viol da gamba was chosen until later in the Baroque, when the cello emerged as a stronger-voiced instrument for larger ensembles. The viol family differed from the violin family in a couple of important ways: its shoulders were sloped, not horizontal, and gut frets were tied around the fingerboard at specific intervals to allow the player to play specific pitches more cleanly than on an unfretted instrument. One of the difficulties of this instrument was, in fact, the frets, which had to be kept in place; if they became loose and moved, the tuning became impossibly unstable. The bowing for a viol da gamba was from an underhand position. Occasionally a bassoon might be the bass reinforcement.

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment Principal cello, Jonathan Manson

Viola da Gamba

Viola da Gamba

Other early Baroque instruments used as soloists were cornettos, trumpets, sacbuts and bassoons. The trumpets and sacbuts were very old. Trumpets had no valves and were associated with military or official municipal or court functions. Sacbuts were smaller, softer-voiced predecessors to the trombone and like the trombone used a slide; for this reason they could double voices in any key and were used to assist in polyphonic music in churches during the Renaissance. The cornetto is not a modern cornet (a broader-bore trumpet-type instrument) but rather a curved, conical-bore wooden tube wrapped in leather and used a trumpet-like mouthpiece. Its sound is somewhat like a muted trumpet.

|

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment - David Blackadder

Baroque Trumpet |

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment - David Chatterton

Baroque Contrabassoon |

|

His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts - Adam Woolf

Baroque Sackbutt |

His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts - Jeremy West

Baroque Cornett (cornetto) |

The bassoon and later the oboe, double-reed instruments very similar to the modern versions, were other solo sounds. Transverse flute and recorder are also solo instruments that are often erroneously perceived today as interchangeable. Recorders are vertical flutes in which air is blown across a sharp edge in a cut-away mouthpiece or fipple, while in the flute air is blown across a blowhole in the side of a tube. Although both were usually made of wood, the sounds they produce are very different—the flute being the softer, almost dove-like.

|

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment - Lisa Beznosiuk

Baroque Flute |

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment - Katharina Spreckelsen

Baroque Oboe |

Early concertos:

The earliest concertos, and for that matter sonatas, were usually single-movement works with contrasting sections. Some early composers of works called concerto are Biagio Marini (1587-1663), Salamone Rossi (1570-1630), Andrea Gabrieli (1510-1586) and his nephew Giovanni Gabrieli (1553-1612), Lodovico Viadana (1560-1627), Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), and Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672). Those familiar with early Baroque music will perhaps wonder at the inclusion of composers such as Rossi, Giovanni Gabrieli, Monteverdi, and Schütz in this list, as they are known for their extensive vocal compositions and less for their instrumental music. At the time the term “concerto” enters the musical vocabulary, though, works with voices accompanied by instruments differed from the tradition of all-vocal or all-instrumental composition. The new-style works, with the mixture of voices and instruments, were often termed concerto, for their composers were employing the continuo (bass and harmonizing instrument) and often other contrasting solo instruments along with vocal soloists or chorus. Furthermore, a great proportion of works entitled “concerto” in the early Baroque were sacred, usually motets (either solo or choral or both) intended for church use. Even liturgy such as Vespers and the Mass was set in this manner, conforming to the new style then being developed in Italy, particularly. We can see just how undifferentiated the terms sinfonia, sonata, and concerto were in the first half of the 17th century by looking at a couple of composers’ own designations for their works: Sinfonici concerti…(“Symphonic Concertos…”, Ucellino) and Il primo libro de motetti e sonate concertati…(“The First Book of Motets and Concerted Sonatas…”, Merula).

The earliest concertos, and for that matter sonatas, were usually single-movement works with contrasting sections. Some early composers of works called concerto are Biagio Marini (1587-1663), Salamone Rossi (1570-1630), Andrea Gabrieli (1510-1586) and his nephew Giovanni Gabrieli (1553-1612), Lodovico Viadana (1560-1627), Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), and Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672). Those familiar with early Baroque music will perhaps wonder at the inclusion of composers such as Rossi, Giovanni Gabrieli, Monteverdi, and Schütz in this list, as they are known for their extensive vocal compositions and less for their instrumental music. At the time the term “concerto” enters the musical vocabulary, though, works with voices accompanied by instruments differed from the tradition of all-vocal or all-instrumental composition. The new-style works, with the mixture of voices and instruments, were often termed concerto, for their composers were employing the continuo (bass and harmonizing instrument) and often other contrasting solo instruments along with vocal soloists or chorus. Furthermore, a great proportion of works entitled “concerto” in the early Baroque were sacred, usually motets (either solo or choral or both) intended for church use. Even liturgy such as Vespers and the Mass was set in this manner, conforming to the new style then being developed in Italy, particularly. We can see just how undifferentiated the terms sinfonia, sonata, and concerto were in the first half of the 17th century by looking at a couple of composers’ own designations for their works: Sinfonici concerti…(“Symphonic Concertos…”, Ucellino) and Il primo libro de motetti e sonate concertati…(“The First Book of Motets and Concerted Sonatas…”, Merula).

|

Marini's "Sonata la Monica"

Monica Huggett, violin - Ensemble Galatea, Paul Beier |

Rossi's "Sinfonia grave a 5"

Il Giardino Armonico |

|

Andrea Gabrieli's "Ricercar a 8"

Symposium Musicum |

Giovanni Gabrieli's "In ecclesiis"

Taverner Choir, Taverner Consort, Taverner Players, Andrew Parrott |

|

Viadana's "4 Sinfonies Musicali"

Académie Strumentale Italiana, Alberto Rasi |

Monteverdi's "Concerto (1619)"

Edwin Loehrer, Orchestre Societa Cameristica Di Lugano |

Schütz, a north German Protestant composer, twice visited Venice, the seat of the most adventuresome concerted music, to learn the newest musical styles there. His first visit was specifically to study with Giovanni Gabrieli, the master of polychoral writing in the spectacular Basilica of San Marco. Schütz left Venice in 1612 just after Gabrieli’s death, and back in his homeland composed a number of sacred polychoral works on Psalm texts (1619). In these works, he contrasted two groups of performers. He returned again to Venice in 1628 during Monteverdi’s tenure at San Marco, and again picked up the newest style of composing--the concerted style with multiple solo instruments, voices and continuo rather than the polychoral style. From this shorter visit flowed an enormous body of work in the more flexible Monteverdi style, including collections of Psalm settings and motets, and even settings of the Passions and Christmas story. Among the collections were three sets of “Sacred Symphonies” and two sets of “Little Spiritual Concerts”, continuing to reflect the application of the two terms symphony and concert(o) to sacred music using both voices and a variety of instruments. The size of the ensembles varies greatly among the sets as Schütz dealt with the horrendous decimation of performers who were taken into the raging Thirty-Years War (1618—1648).

Schütz's "Symphonie Sacrae"

Concerto Palatine, Bruce Dickey

Concerto Palatine, Bruce Dickey

Types of concerto:

The strictly instrumental concerto was differentiated from the sinfonia and the sonata in the second half of the 17th century. There were two principal types of concerto by this time:

The strictly instrumental concerto was differentiated from the sinfonia and the sonata in the second half of the 17th century. There were two principal types of concerto by this time:

Solo concerto: a single featured instrument contrasted against a larger ensemble, consisting primarily of strings, and the Baroque’s ever-present foundation sound, the continuo. This type was championed by Bologna composer Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709) as he produced a number of trumpet solo works accompanied by an ensemble. Torelli’s trumpet, being without valves, could produce only overtone pitches above the instrument’s fundamental, and was thus able to produce mostly chord outlines, and, at a higher range, a basic scale; the accompaniment was simpler, to accommodate the limited trumpet melodies, and primarily chordal (homophonic) rather than contrapuntal. Torelli then adapted this style to string works. Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), working first in Bologna and then in Rome, developed the solo concerto particularly for violin; in these works the solo violin was accorded truly virtuosic features. Corelli’s concertos were often in more than three movements, alternating slow, fast, slow and fast. Torelli and Corelli influenced later composers, especially Antonio Vivaldi in Venice, whose concerto style and format became the model for the late Baroque solo concerto.

|

Torelli's "Trumpet Concerto in D Major"

Voices of Music, Dominic Favia, baroque trumpet |

Corelli's "Sonata per Violino" Op. 5, No. 7

Rémy Baudet, Jaap ter Linden, Mike Fentross & Pieter-Jan Belder |

Vivaldi's "Violin Concerto in A Minor", RV356, Op.3, No. 6

Itzhak Perlman, violin

Itzhak Perlman, violin

Concerto grosso: a small ensemble of soloists, called the concertino (small contrasting group) in contrast to a fuller body, almost always strings, called the ripieno (full group—think chillis rienos, or filled peppers!), plus, of course, the continuo. The concept of contrasting ensembles, as oppose to solo against ensemble, is actually as old as the concerto concept itself. In the second half of the 17th century, Arcangelo Corelli established a pattern for the concerto grosso with multiple movements and alternating homophonic (chordal) and contrapuntal textures. In some cases these were suitable for church (da chiesa), having no dance movements, and others were for chamber or secular uses (da camera). The secular concertos had movements with dance titles, characteristics, and structures and were thus related to the Baroque suite. In the great majority of Corelli’s concertos, the concertino consisted of two violins and the ripieno of a string ensemble. Corelli notably published six sets of concertos. One of his most famous works is the “Christmas Concerto”, Op. 6, no. 8 in G minor, a concerto da chiesa which is part one work in a set of both church and chamber concertos published in 1714 in Amsterdam.

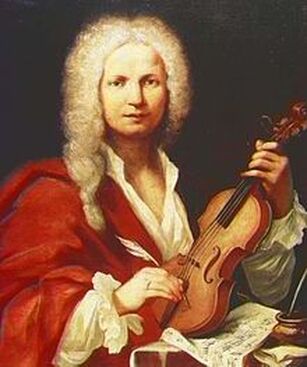

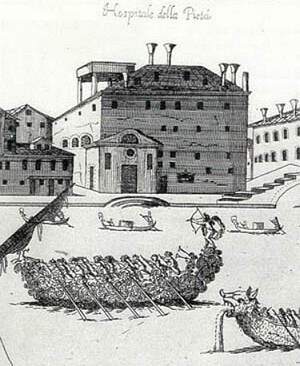

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), working primarily in Venice, is arguably the preeminent concerto composer of the Baroque. Working from his predecessors’ models, he composed both solo concertos and concerti grossi in both the Corellian pattern and the Torellian pattern. That is, he wrote concertos using anywhere from three to seven movements. The three-movement concertos became the standard through not only the end of the Baroque but the Classical era as well. He also developed a third type called ripieno concerto, which is somewhat similar to an early classical symphony. Composing for the girls and young women of the Ospidale della Pietà, one of Venice’s several orphanage-schools for girls,

Vivaldi employed as soloists a variety of winds, brass, and lower string instruments as well as violins. He expanded the possibilities for continuo sounds by using not only harpsichords and organs for sacred and secular works, respectively, but also chord-producing instruments such as theorbos and mandolins as well. He also ventured into descriptive writing, as is well-known from his Quattro Stagione (Four Seasons). He composed hundreds of concertos, many of them grouped into sets of six or twelve for publication.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vivaldi's "The Four Seasons"

Netherlands Bach Society - Violin and direction: Shunske Sato

Netherlands Bach Society - Violin and direction: Shunske Sato

Vivaldi’s format for the Torellian-type concerto is worth noting, as it was adopted by composers all over Europe. Its three movements are in a fast-slow-fast order. The first movement has a particular arrangement of its thematic contents called “ritornello form”. In this, the ripieno presents a theme called the ritornello—the returning idea that binds the movement in to a whole. It usually consists of several different-sounding ideas in unison, or at least homophonic style. Then the soloist enters with its own theme in the home key, accompanied by the repieno. Next, the ripieno and the soloist alternate, using several of the ideas (usually abbreviated) from their original presentations, and travel to related harmonic areas before returning to the home key for a final statement of the ritornello by both soloist and ripieno. Vivaldi’s solo concertos’ second movements vary widely in style. They might be a series of interesting harmonies, or feature virtuosic work by the soloist, or be very dramatic, or ethereal. The fast third movement tends to be more homophonic and energetic.

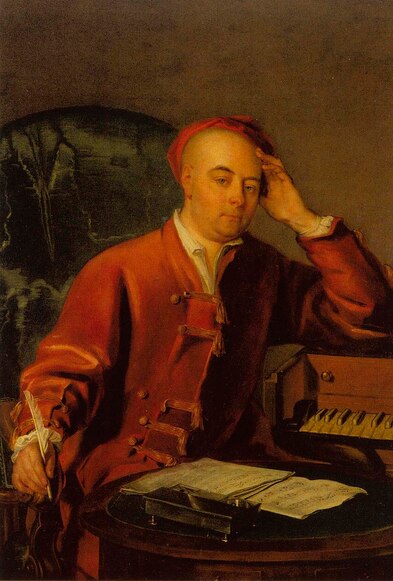

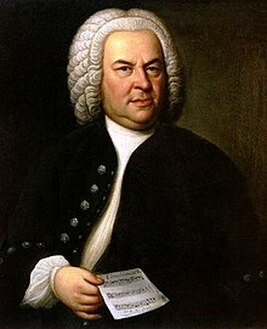

The latest Baroque inheritors of Corelli’s and Vivaldi’s concerto styles were George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Corelli’s music especially influenced Handel, who had become acquainted with the Italian while he was living in Rome. Handel’s six concerti grossi comprising his Opus 3 (pub. 1734) have diverse instruments in the concertinos (such as flute or recorder and one or more oboe), but most of the twelve of his Opus 6 (pub. 1739) feature two violins and cello against the ripieno. Several of the concertos specify organ in the continuo or as soloist.

Bach, however, was so strongly taken by Vivaldi’s concertos that he transcribed six of them for organ. His own later solo concertos clearly reflect Vivaldi’s three-movement construction and first-movement “ritornello form”. His works are major strides forward in concerto literature: not only eight solo concertos for harpsichord, but also three concerti grossi for two harpsichords, two for three harpsichords, and one for four harpsichords!

An interesting note here is that transcription played an big part in swelling Bach’s performing repertoire—and was perfectly acceptable in his day. For instance, he transformed the marvelous first solo harpsichord concerto, in D minor, BWV 1052, into a violin concerto and also a solo organ concerto. Some of the other harpsichord concertos are also “reconstructed” from lost concerti for other instruments.

Bach's "Harpsichord Concerto No. 1 in D Minor", BWV 1052

Jean Rondeau, harpsichord

Jean Rondeau, harpsichord

Bach's "Konzert d-Moll", BWV 1052 für Orgel

Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Iveta Apkalna, Orgel, Riccardo Minasi, Dirigent

Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Iveta Apkalna, Orgel, Riccardo Minasi, Dirigent

Bach's "Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Minor", BWV 1052R

Netherlands Bach Society, Shunske Sato, conductor and violin, Johannes Ruckers, harpsichord

Netherlands Bach Society, Shunske Sato, conductor and violin, Johannes Ruckers, harpsichord

Probably the most important set of concertos by Bach are the six “Brandenburg Concertos”. Bach wrote them over a period from 1708 to 1718, while he worked in Weimar and then Cöthen. Their name as a set comes from Bach’s having packaged them as a kind of job application to Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg, in 1721. The Margrave never responded to Bach—it seems he didn’t even open the gift--and Bach took a new job in Leipzig instead. Maybe it’s just as well. Bach had the services of an exceptional group of musicians in Cöthen and wrote for their capabilities (and his own, since he probably performed at the keyboard with them), and very likely Christian Ludwig’s court would not have had the variety and technically superior forces to perform the spectacularly demanding music represented in these concerti.

The Brandenburgs represent a great diversity of solo instruments (the ripieno instruments are in parentheses):

Concerto 1, in F: 2 horns, 3 oboes, violino piccolo, bassoon (strings and continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major", BWV 1046: I. [Allegro]

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Concerto 2, in F: trumpet, recorder, oboe, violin (strings and continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major", BWV 1047: III. Allegro assai

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Concerto 3, in G: 3 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos (continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G Major", BWV 1048: I. [Allegro]

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Concerto 4, in G; violin, 2 recorders (strings and continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 4", BWV 1049 I. [Presto]

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Concerto 5, in D: flute, violin, harpsichord (strings and continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 5", BWV 1050 [1st movement]

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Concerto 6, in B-flat: 2 violas, 2 violas da gamba, cello (continuo).

Bach's "Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B Flat Major", BWV 1051: III. [Allegro]

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

Apollo's Fire, Jeannette Sorrell, director

The six concertos represent a blend of concerto types—solo, grosso, and ripieno. The third and sixth are ripieno concertos, with no soloist highlighted. The first and second are concerti grossi, with soloists clearly standing out; in the second, Bach employs soloists from disparate environments—two “indoor” instruments and two “outdoor”, military instruments. The fifth is a blend of grosso and solo concerto, for while it definitely has flute and violin soloists, the harpsichord breaks out of its accompanying function in the continuo and takes center stage with a soloist’s unaccompanied cadenza in the first movement.

Michael Marissen, in The Social and Religious Designs of J. S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos (Princeton University Press, 1995), considers the entire set of six concertos to be a monumental whole, and goes into some fascinating detail to reveal even more wonders of Bach’s compositional imagination. Here are some of my favorite highlights from Marissen:

Instrumental hierarchies of the 18th century are important—gotta know the players to understand the dynamic at work among them.

Strings:

Violino piccolo is a major 3rd higher than violin, associated with Poland, which had a Saxon king at that time.

Solo principal violin: court instrument, highest paid musician except for Kapellmeister—great prestige.

Viola: ripieno instrument (one of the “chorus girls”); accompaniment. Low pay, low prestige.

Cello: ripieno instrument; accompaniment.

Viola da gamba: soloist, highly specialized, highly respected.

Violone: in these works, a kind of oversized gamba, basically close to the viola.

Brass:

Horns: the hunt; nobility, highest social order.

Trumpets: military, regal, festive.

Woodwinds:

Flute: middle-range in prestige, higher than recorder.

Recorder: chamber instrument, oboist’s second instrument; mostly amateur, middle-class instrument.

Oboe: military bands; Stadtpfeiffer, municipal musicians, respectable but lower than court musicians.

Bassoon: accompaniment, continuo foundation.

Strings:

Violino piccolo is a major 3rd higher than violin, associated with Poland, which had a Saxon king at that time.

Solo principal violin: court instrument, highest paid musician except for Kapellmeister—great prestige.

Viola: ripieno instrument (one of the “chorus girls”); accompaniment. Low pay, low prestige.

Cello: ripieno instrument; accompaniment.

Viola da gamba: soloist, highly specialized, highly respected.

Violone: in these works, a kind of oversized gamba, basically close to the viola.

Brass:

Horns: the hunt; nobility, highest social order.

Trumpets: military, regal, festive.

Woodwinds:

Flute: middle-range in prestige, higher than recorder.

Recorder: chamber instrument, oboist’s second instrument; mostly amateur, middle-class instrument.

Oboe: military bands; Stadtpfeiffer, municipal musicians, respectable but lower than court musicians.

Bassoon: accompaniment, continuo foundation.

Knowing this hierarchy, it is interesting to observe Marissen’s interpretation of the instrumentation of the six concertos. Those who know Bach’s religious convictions will recognize some moralizing in the mix—the equality of all humanity under the divine reign of God; and the first shall be last, the last first in the Kingdom:

- Concerto I: the struggle for attention among soloists; the most unlikely are featured, others “brought down” from their exalted social position.

- Concerto II: a rather democratic model in which soloists of very diverse background are treated with great equality and bear rather equal responsibility.

- Concerto III: no real attempt on the part of any one soloist to take over and become the center of attention; conventional stratification between string sections is leveled and equalized.

- Concerto IV: a struggle between two kinds of soloists—violin and recorders. Recorders on the lowest social stratum challenge the violin at the top. Recorders have greater musical weight while the violin gets attention through flashy but empty virtuosity and even goes into “histrionics” at the end of the first movement.

- Concerto V: completely overthrows the conventions in Movement 1. It starts like a flute concerto, a novelty for that time. The harpsichord, however, gradually takes over as soloist until it actually “becomes the ensemble”, even taking away the impact of the return of the other instruments at the end of the movement.

- Concerto VI: reversal of roles for the gambas, which are usually soloistic. Here they become the accompaniment or at best a secondary solo, while “humble” violas serve as principal soloists.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.