- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

"MAGIC FLUTE" OVERVIEW ESSAY

Arrival of Sarastro on a chariot pulled by lions, from a 1793 production in Brno. Pamina appears at left, Papageno at right. In the background are the temples of Wisdom, Reason, and Nature.

MOZART'S MAGIC FLUTE:

Overview and an Interpretation

by Judith A. Eckelmeyer

Mozart’s Magic Flute, one of the most popular operas in the repertoire, has a longstanding reputation as being confused, somewhat disconnected, and certainly full of symbols at once puzzling and vaguely sinister. The plot seems so scrambled that many productions seek to “correct” the story or, as an extreme measure, leave some of it out. The text has been much abridged and modified over the two centuries since it saw daylight. It has become fair game for just about any kind of mutation to ensure audience satisfaction. The only constant is the music that Mozart wrote. And even that has been subject to reordering, supposedly to support a “clarification” of the story.

So much lore surrounds the opera, much of it associated with the history and rituals of Freemasonry, that today it is hard to penetrate to the original work.

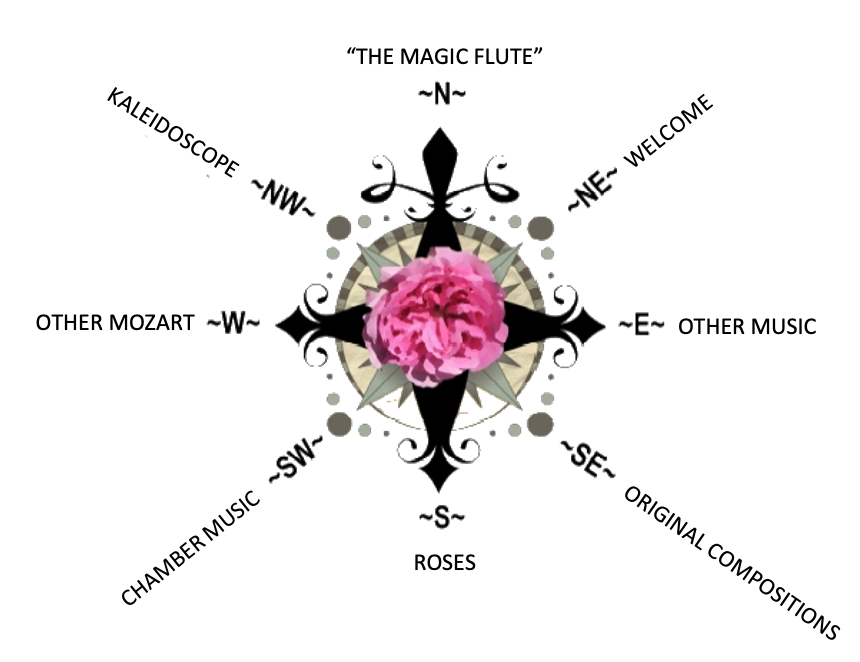

Another entry on this website, Magic Flute (north direction on the compass rose) “Basics”, will provide a careful synopsis of the opera as well as foundational information about the work; you are invited to visit that section at your pleasure.

Much of the information that flows from performances of The Magic Flute today, or commentaries about it in newspapers and magazines available to the general public, touches little of recent research about the opera. I hope to promote a better understanding of this important information for those who know and love the opera and would like to deepen their appreciation of the remarkable details it contains.

Is there a “real” Magic Flute? Is there a purpose or meaning intrinsic to the opera’s unusual plot, text and stage design? Was it the product of only two people—Mozart and the named librettist Emmanuel Schikaneder—or were there more hands involved? And why?

These are some of the questions that I will address in this extended essay. I hope it will encourage you to see for yourself more reasons why The Magic Flute is worthy of further study as well as frequent performance.

I. INTRODUCTION

In August of 1791, Mozart interrupted the completion of The Magic Flute to compose La Clemenza di Tito to fulfill a commission for the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II, in Prague, as King of Bohemia. Leopold had in the previous year already been crowned Holy Roman Emperor, succeeding his late brother Joseph II, who had just died. But Leopold’s accession specifically to the throne of Bohemia had particular ramifications, as we shall soon see.

Leopold undertook his reign as Holy Roman Emperor and Emperor of Austria seated on a virtual dynamite keg. Joseph, before him, had introduced a number of reforms emanating from his Enlightenment convictions. Many saw his policies as irresponsible, if not downright dangerous, to the stability of the Austrian Empire. The extreme of reform activity had been undertaken two years earlier in France, with the beginning of the Revolution there. Austria was particularly sensitive to the potential vulnerability of the monarchy not only because of the controversy over Joseph's reforms but also because Marie Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI, was the sister of Joseph and Leopold. Leopold, with his own more careful and cautious approach to governance, began reversing some of the reforms that Joseph had undertaken. In support of Leopold observers began publishing opinions that his reign would be a time of peace and prosperity in Austria—an AGE OF GOLD.

In September of 1791, after the premiere of La Clemenza di Tito, Mozart returned to Vienna, completed The Magic Flute, and saw its premiere on September 30 in the popular Theater "Auf der Wieden", just outside the city's walls. The opera continued in production there with great success. A year later, the original Viennese production was taken to Prague. Thereafter, the opera was performed in numerous locations in local productions which adapted the work for their own region.

From the very first performance, however, the opera generated many questions. Its music was seen to be on a higher plane than the libretto. The libretto exhibited strange shifts in literary style and even seemed to break off at the end of Act I and move in a new direction, suggesting a kind of interruption in the writing process. Scholars found the work unusually eclectic in its symbols and themes, drawing from widely unrelated sources. Until the last three decades of the 20th century, the accepted principal sources for themes in the work generally encompass the following:

This list of extraordinarily diverse feeders for the opera gives an idea of the confusion that has sent scholars on a hunt for the "real" Magic Flute for the last two centuries. In addition to these, new research in the 20th century has added several more source themes:

I will discuss these new themes in subsequent sections. However, it has been my contention for a long time that the themes within the opera are interlocked in a common stream; no one theme is the “real” story. My own interpretation, which I present in the next section, works in generalities of process rather than in allegorical or metaphorical specificity. I believe it will be possible to see that, in many ways, the new themes, along with the earlier ones, are not mutually exclusive when interpreting the opera for meaning or purpose. I hope to reveal the correlations as this essay progresses.

II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSICAL STRUCTURE AND PLOT TOWARD A MEANING FOR THE OPERA

My own studies have found that the music of the opera is uniquely unified. I prepared two extensive examinations of the musical unity: Recurrent Melodic Structures and Libretto Continuity in Mozart’s “Die Zauberflöte, UMI ATT 6907734, and “Structure as Hermeneutic Guide to The Magic Flute”, The Musical Quarterly (New York: Macmillan, Inc.) 72:1 (1968), 51-73. Further, I have found that there is a recognizable coherence in the plot, if one takes into account not only the sung text but also the spoken dialogue, a characteristic of the theatrical genre called Singspiel that was being created here. The complete text and stage directions are available in Vol. 2 of my monograph, The Cultural Context of Mozart's "Magic Flute" (The Edwin Mellen Press, 1991). Once the coherence of both plot and music is understood, and joined to a body of cultural connections (more fully explored in Vol. 1 of The Cultural Context of Mozart's "Magic Flute"), one begins to recognize the meaning that is ultimately imparted by the work as a whole. This meaning is the larger subject of this essay.

The macrostructure of the opera is key to understanding the meaning of The Magic Flute. The plot functions like a Hegelian dialectic, parallelled exactly by the musical process called sonata-allegro form, the overall construct of the music in the opera. Here is the organization in a nutshell:

Thesis = Overture, in the key of E-flat, through Pamina/Papageno duet in roughly the middle of Act I, just before the Finale begins. This section musically functions as the “first theme group” of a sonata-allegro structure. Dramatically it is dominated by the Queen of the Night. In this section the Queen commissions Prince Tamino to rescue her daughter Pamina from the evil Sarastro. Tamino is given a magic flute to help him, and the birdcatcher Papageno is sent with him, and also has magic bells to help him.

Antithesis = Act I Finale beginning with Tamino's being guided by Three Boys into Sarastro's realm. The key is C major; musically this section functions as the “contrasting key group” of a sonata-allegro structure. Dramatically, in this section Sarastro's society dominates, and a new perspective is introduced in the plot: that Sarastro may not be evil, and that to rescue Pamina, Tamino will have to prove himself worthy in the eyes of the Initiates of the Temple of Wisdom.

Synthesis is in 2 parts:

Act II beginning, with early trials of Tamino, Papageno and Pamina's trials, including her repudiation of both Monostatos, her lecherous overseer, and her mother, the Queen of the Night, who had tried to force her to commit murder. Musically this section is the “development” portion of the sonata-allegro structure; the keys of the successive numbers vary greatly, but in general move away from the home key of E-flat and then back toward it.

And:

Act II Finale, beginning at Pamina's attempted suicide, from which the Three boys rescue her. Musically this is the “recapitulation” of the sonata-allegro structure. The key is once again E-flat major; there are parallels with the opening of the opera, and the work concludes in E-flat. Dramatically, all threads are tied up, each character reaches his/her final stage, the goal of the hero and heroine is achieved. Pamina is recognized as a worthy partner to Tamino, and the two are united through the trials of fire and water. As they complete these trials, a brilliant light shines from within the Temple of Wisdom and voices invite them to enter. Papageno is saved from suicide by the Three Boys and is united with his mate Papagena. The Queen and her followers fail to overcome Sarastro and his followers and sink into the shadows. As the sun rises, Tamino and Pamina, in priestly garb, appear with Sarastro and the Initiates of the Temple of Wisdom, dedicated to Isis and Osiris. At this final moment of the opera, the libretto states that the entire theater becomes a sun.

This summary generates three principal observations:

The dialectic process underscores the process of change, of improvement, of becoming;

The structure replicates the concept of the alchemical process, and especially the heirosgamos -- isolation or identification, purification, and union of noble metals gold and silver, achieving the "philosopher's stone" or eternal life (incorruptibility, imperishability, etc.)

The Magic Flute is a didactic opera intended to affect the audience; the creators of it presented: aphorisms, short statements of moral tenets in simple poetry that the middle- and lower-classes in the audience would understand immediately; the internal (small) enlightenment of Tamino and Pamina; the external (universal) enlightenment of audience at the end, when the theater (the stage) becomes a sun.

I suggest that these three aspects together support a purpose for the opera, namely: to point the way to social and political reform in Austria at a time when a new, young ruler had ascended the throne of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire, and when this ruler's sister and brother-in-law in France were removed from power by the revolution there. The goal, then, was a bloodless revolution in Austria. As I have explained in both The Cultural Context of Mozart’s “Magic Flute” and my article “Novus Ordo Seclorum: Some Political Implications in the libretto of The Magic Flute” in Eighteenth-Century Life (University of Pittsburgh) 5:4 (1979), 78-89, this was not to advocate overthrow of the monarchy (for Tamino and Pamina retain their status as royalty and anticipate that they will rule as king and queen), but rather an attempt to effect wise governance by a new ruler who will have been enlightened by purifying and educating trials so as to bring about a new beginning for Austria—an Age of Gold, a New Jerusalem, a veritable second Eden. Fuller support for this position will be given in Sections IV-VI below.

III. NEW THEMES: CULTURAL MEMORY OF MYSTERY; SPIRITUAL/PSYCHOLOGICAL WHOLENESS; METALLURGY; MINING; NUMBERS; ALCHEMY

If the history of research on The Magic Flute is any indication, the 21st-century world has not yet found a common satisfactory interpretation of the opera. In fact, one wonders if it is indeed possible to come to a unified understanding of this multilayered work, interwoven as it is with so many cultural threads. However, from the middle of the past century, a number of scholars have presented new directions for seeing the specifics. Each interpretive configuration has its benefits and contributes to our better understanding of the richness of the supposed fairy-tale opera.

Cultural memory of the Mystery

Although it seems on the surface quite obvious that The Magic Flute is about an Egyptian mystery religion, until recently no one has seriously tackled the “elephant in the room”. In the early 2000s, the noted Egyptologist Jan Assmann contacted me to ask about my study of the opera’s music. I had read Professor Assmann’s Moses the Egyptian some years before and was surprised by his interest in the Mozart opera, which I had thought was using the Egyptian setting for effect rather than for a genuine representation of the mysteries of Isis and Osiris. By that time I had obtained Ignaz von Born’s article “Ueber die Mysterien der Aegyptier”, which was the cornerstone of the first issue of the Journal für Freymaurer in 1783; the article was well known to have provided some of the details within the opera. (An English translation of the article, by Renata Cinti, is available in Volume 2 of my Cultural Context of Mozart’s “Magic Flute”.) Professor Assmann, though, saw the opera as much more than a linking of the Egyptian mystery religion and its pair of divinities with 18th-century Freemasonry. In his Die Zauberflöte, Oper und Mysterium (Carl Hanser Verlag, 2005), he interprets the opera as a presentation of a mystery—a sacred, restricted experience that transforms the initiate with special understanding of life. In this, he argues, the opera conveys a spiritual connection with very ancient human cultural memories, of which the mystery religions of antiquity were a part. Professor Assmann’s work brings to light a depth of recognition which the opera’s creators had for the nature of the mystery religion (indeed, in the three years of its existence, the Journal für Freymaurer contained articles on a number of mystery religions of ancient cultures) and the relationship between mystery initiation and ancient drama. As I have already commented, the concept of a transformative experience for the initiate—the audience member—is built into The Magic Flute in its very libretto. And it is my contention that the opera was about this transformative experience.

Spiritual/Psychological Wholeness

Three scholars have approached the opera from the standpoint of human spiritual or psychological experience.

Erich Neumann, a student of Carl Jung, interpreted the story in Zur Psychologie, in 1953; Esther Doughty’s English translation of Neumann’s essay was published in Quadrant, 2 (1978) 5-32, the journal of the C. G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology. Neumann holds that the multiple layers of the opera function like a dream, drawing from the conscious and the unconscious. Using archetypal events and characters the opera depicts the initiation and “night journey” of the hero, the individuation of the feminine lead character (Pamina), and the coniunctio of the hero and his consort.

In “A New Metaphor for The Magic Flute” in European Studies Review, 5 (1975) 229-275, Dorothy Koenigsberger examines the opera in the context of the history of science, medicine, natural philosophy, and alchemy. Reaching back to ancient writers, she sees in the opera not only the symbols of initiation, but more—an allegory of the progress of a single soul, through purification and joining of the anima and animus, that is the female and male aspects of the individual, to wholeness, to perfection. Each character in the opera is an aspect of the psyche. Koenigsberger is perhaps the first to have commented that the various symbols in the opera relate to each other like a “layer cake”, all of them complementary and all with a common dramatic purpose. Her article is well worth reading for its rich analysis of the opera.

Jocelyn Godwin, in “Layers of Meaning in ‘The Magic Flute’” in The Musical Quarterly 65 (1979) 471-492, reads the opera from both eastern and western esoteric traditions. He ultimately explains the plot in Jungian terms, which he sees connected to the long history of esotericism that also found its way into Freemasonry, and thus into Mozart’s milieu.

So much lore surrounds the opera, much of it associated with the history and rituals of Freemasonry, that today it is hard to penetrate to the original work.

Another entry on this website, Magic Flute (north direction on the compass rose) “Basics”, will provide a careful synopsis of the opera as well as foundational information about the work; you are invited to visit that section at your pleasure.

Much of the information that flows from performances of The Magic Flute today, or commentaries about it in newspapers and magazines available to the general public, touches little of recent research about the opera. I hope to promote a better understanding of this important information for those who know and love the opera and would like to deepen their appreciation of the remarkable details it contains.

Is there a “real” Magic Flute? Is there a purpose or meaning intrinsic to the opera’s unusual plot, text and stage design? Was it the product of only two people—Mozart and the named librettist Emmanuel Schikaneder—or were there more hands involved? And why?

These are some of the questions that I will address in this extended essay. I hope it will encourage you to see for yourself more reasons why The Magic Flute is worthy of further study as well as frequent performance.

I. INTRODUCTION

In August of 1791, Mozart interrupted the completion of The Magic Flute to compose La Clemenza di Tito to fulfill a commission for the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II, in Prague, as King of Bohemia. Leopold had in the previous year already been crowned Holy Roman Emperor, succeeding his late brother Joseph II, who had just died. But Leopold’s accession specifically to the throne of Bohemia had particular ramifications, as we shall soon see.

Leopold undertook his reign as Holy Roman Emperor and Emperor of Austria seated on a virtual dynamite keg. Joseph, before him, had introduced a number of reforms emanating from his Enlightenment convictions. Many saw his policies as irresponsible, if not downright dangerous, to the stability of the Austrian Empire. The extreme of reform activity had been undertaken two years earlier in France, with the beginning of the Revolution there. Austria was particularly sensitive to the potential vulnerability of the monarchy not only because of the controversy over Joseph's reforms but also because Marie Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI, was the sister of Joseph and Leopold. Leopold, with his own more careful and cautious approach to governance, began reversing some of the reforms that Joseph had undertaken. In support of Leopold observers began publishing opinions that his reign would be a time of peace and prosperity in Austria—an AGE OF GOLD.

In September of 1791, after the premiere of La Clemenza di Tito, Mozart returned to Vienna, completed The Magic Flute, and saw its premiere on September 30 in the popular Theater "Auf der Wieden", just outside the city's walls. The opera continued in production there with great success. A year later, the original Viennese production was taken to Prague. Thereafter, the opera was performed in numerous locations in local productions which adapted the work for their own region.

From the very first performance, however, the opera generated many questions. Its music was seen to be on a higher plane than the libretto. The libretto exhibited strange shifts in literary style and even seemed to break off at the end of Act I and move in a new direction, suggesting a kind of interruption in the writing process. Scholars found the work unusually eclectic in its symbols and themes, drawing from widely unrelated sources. Until the last three decades of the 20th century, the accepted principal sources for themes in the work generally encompass the following:

- Ignaz von Born’s essay on the Egyptian mysteries of Isis and Osiris in Journal für Freymaurer, 1783

- Freemasonry’s symbols and rituals, including the day/night or light/darkness dichotomy

- Fairy tales collected and edited by Christoph Martin Wieland in Dschinnistan, 1786

- Orpheus legend and other classical myths

- Shakespeare’s The Tempest

- Abbé Jean Terrasson’s Sethos, 1732, about a fictional Egyptian prince

- Viennese Singspiel tradition and the “magic opera” tradition

This list of extraordinarily diverse feeders for the opera gives an idea of the confusion that has sent scholars on a hunt for the "real" Magic Flute for the last two centuries. In addition to these, new research in the 20th century has added several more source themes:

- The deep cultural memory of initiation into mystery religion

- Spiritual/psychological wholeness

- Mining and mineralogy

- Numbers

- Alchemy

I will discuss these new themes in subsequent sections. However, it has been my contention for a long time that the themes within the opera are interlocked in a common stream; no one theme is the “real” story. My own interpretation, which I present in the next section, works in generalities of process rather than in allegorical or metaphorical specificity. I believe it will be possible to see that, in many ways, the new themes, along with the earlier ones, are not mutually exclusive when interpreting the opera for meaning or purpose. I hope to reveal the correlations as this essay progresses.

II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSICAL STRUCTURE AND PLOT TOWARD A MEANING FOR THE OPERA

My own studies have found that the music of the opera is uniquely unified. I prepared two extensive examinations of the musical unity: Recurrent Melodic Structures and Libretto Continuity in Mozart’s “Die Zauberflöte, UMI ATT 6907734, and “Structure as Hermeneutic Guide to The Magic Flute”, The Musical Quarterly (New York: Macmillan, Inc.) 72:1 (1968), 51-73. Further, I have found that there is a recognizable coherence in the plot, if one takes into account not only the sung text but also the spoken dialogue, a characteristic of the theatrical genre called Singspiel that was being created here. The complete text and stage directions are available in Vol. 2 of my monograph, The Cultural Context of Mozart's "Magic Flute" (The Edwin Mellen Press, 1991). Once the coherence of both plot and music is understood, and joined to a body of cultural connections (more fully explored in Vol. 1 of The Cultural Context of Mozart's "Magic Flute"), one begins to recognize the meaning that is ultimately imparted by the work as a whole. This meaning is the larger subject of this essay.

The macrostructure of the opera is key to understanding the meaning of The Magic Flute. The plot functions like a Hegelian dialectic, parallelled exactly by the musical process called sonata-allegro form, the overall construct of the music in the opera. Here is the organization in a nutshell:

Thesis = Overture, in the key of E-flat, through Pamina/Papageno duet in roughly the middle of Act I, just before the Finale begins. This section musically functions as the “first theme group” of a sonata-allegro structure. Dramatically it is dominated by the Queen of the Night. In this section the Queen commissions Prince Tamino to rescue her daughter Pamina from the evil Sarastro. Tamino is given a magic flute to help him, and the birdcatcher Papageno is sent with him, and also has magic bells to help him.

Antithesis = Act I Finale beginning with Tamino's being guided by Three Boys into Sarastro's realm. The key is C major; musically this section functions as the “contrasting key group” of a sonata-allegro structure. Dramatically, in this section Sarastro's society dominates, and a new perspective is introduced in the plot: that Sarastro may not be evil, and that to rescue Pamina, Tamino will have to prove himself worthy in the eyes of the Initiates of the Temple of Wisdom.

Synthesis is in 2 parts:

Act II beginning, with early trials of Tamino, Papageno and Pamina's trials, including her repudiation of both Monostatos, her lecherous overseer, and her mother, the Queen of the Night, who had tried to force her to commit murder. Musically this section is the “development” portion of the sonata-allegro structure; the keys of the successive numbers vary greatly, but in general move away from the home key of E-flat and then back toward it.

And:

Act II Finale, beginning at Pamina's attempted suicide, from which the Three boys rescue her. Musically this is the “recapitulation” of the sonata-allegro structure. The key is once again E-flat major; there are parallels with the opening of the opera, and the work concludes in E-flat. Dramatically, all threads are tied up, each character reaches his/her final stage, the goal of the hero and heroine is achieved. Pamina is recognized as a worthy partner to Tamino, and the two are united through the trials of fire and water. As they complete these trials, a brilliant light shines from within the Temple of Wisdom and voices invite them to enter. Papageno is saved from suicide by the Three Boys and is united with his mate Papagena. The Queen and her followers fail to overcome Sarastro and his followers and sink into the shadows. As the sun rises, Tamino and Pamina, in priestly garb, appear with Sarastro and the Initiates of the Temple of Wisdom, dedicated to Isis and Osiris. At this final moment of the opera, the libretto states that the entire theater becomes a sun.

This summary generates three principal observations:

The dialectic process underscores the process of change, of improvement, of becoming;

The structure replicates the concept of the alchemical process, and especially the heirosgamos -- isolation or identification, purification, and union of noble metals gold and silver, achieving the "philosopher's stone" or eternal life (incorruptibility, imperishability, etc.)

The Magic Flute is a didactic opera intended to affect the audience; the creators of it presented: aphorisms, short statements of moral tenets in simple poetry that the middle- and lower-classes in the audience would understand immediately; the internal (small) enlightenment of Tamino and Pamina; the external (universal) enlightenment of audience at the end, when the theater (the stage) becomes a sun.

I suggest that these three aspects together support a purpose for the opera, namely: to point the way to social and political reform in Austria at a time when a new, young ruler had ascended the throne of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire, and when this ruler's sister and brother-in-law in France were removed from power by the revolution there. The goal, then, was a bloodless revolution in Austria. As I have explained in both The Cultural Context of Mozart’s “Magic Flute” and my article “Novus Ordo Seclorum: Some Political Implications in the libretto of The Magic Flute” in Eighteenth-Century Life (University of Pittsburgh) 5:4 (1979), 78-89, this was not to advocate overthrow of the monarchy (for Tamino and Pamina retain their status as royalty and anticipate that they will rule as king and queen), but rather an attempt to effect wise governance by a new ruler who will have been enlightened by purifying and educating trials so as to bring about a new beginning for Austria—an Age of Gold, a New Jerusalem, a veritable second Eden. Fuller support for this position will be given in Sections IV-VI below.

III. NEW THEMES: CULTURAL MEMORY OF MYSTERY; SPIRITUAL/PSYCHOLOGICAL WHOLENESS; METALLURGY; MINING; NUMBERS; ALCHEMY

If the history of research on The Magic Flute is any indication, the 21st-century world has not yet found a common satisfactory interpretation of the opera. In fact, one wonders if it is indeed possible to come to a unified understanding of this multilayered work, interwoven as it is with so many cultural threads. However, from the middle of the past century, a number of scholars have presented new directions for seeing the specifics. Each interpretive configuration has its benefits and contributes to our better understanding of the richness of the supposed fairy-tale opera.

Cultural memory of the Mystery

Although it seems on the surface quite obvious that The Magic Flute is about an Egyptian mystery religion, until recently no one has seriously tackled the “elephant in the room”. In the early 2000s, the noted Egyptologist Jan Assmann contacted me to ask about my study of the opera’s music. I had read Professor Assmann’s Moses the Egyptian some years before and was surprised by his interest in the Mozart opera, which I had thought was using the Egyptian setting for effect rather than for a genuine representation of the mysteries of Isis and Osiris. By that time I had obtained Ignaz von Born’s article “Ueber die Mysterien der Aegyptier”, which was the cornerstone of the first issue of the Journal für Freymaurer in 1783; the article was well known to have provided some of the details within the opera. (An English translation of the article, by Renata Cinti, is available in Volume 2 of my Cultural Context of Mozart’s “Magic Flute”.) Professor Assmann, though, saw the opera as much more than a linking of the Egyptian mystery religion and its pair of divinities with 18th-century Freemasonry. In his Die Zauberflöte, Oper und Mysterium (Carl Hanser Verlag, 2005), he interprets the opera as a presentation of a mystery—a sacred, restricted experience that transforms the initiate with special understanding of life. In this, he argues, the opera conveys a spiritual connection with very ancient human cultural memories, of which the mystery religions of antiquity were a part. Professor Assmann’s work brings to light a depth of recognition which the opera’s creators had for the nature of the mystery religion (indeed, in the three years of its existence, the Journal für Freymaurer contained articles on a number of mystery religions of ancient cultures) and the relationship between mystery initiation and ancient drama. As I have already commented, the concept of a transformative experience for the initiate—the audience member—is built into The Magic Flute in its very libretto. And it is my contention that the opera was about this transformative experience.

Spiritual/Psychological Wholeness

Three scholars have approached the opera from the standpoint of human spiritual or psychological experience.

Erich Neumann, a student of Carl Jung, interpreted the story in Zur Psychologie, in 1953; Esther Doughty’s English translation of Neumann’s essay was published in Quadrant, 2 (1978) 5-32, the journal of the C. G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology. Neumann holds that the multiple layers of the opera function like a dream, drawing from the conscious and the unconscious. Using archetypal events and characters the opera depicts the initiation and “night journey” of the hero, the individuation of the feminine lead character (Pamina), and the coniunctio of the hero and his consort.

In “A New Metaphor for The Magic Flute” in European Studies Review, 5 (1975) 229-275, Dorothy Koenigsberger examines the opera in the context of the history of science, medicine, natural philosophy, and alchemy. Reaching back to ancient writers, she sees in the opera not only the symbols of initiation, but more—an allegory of the progress of a single soul, through purification and joining of the anima and animus, that is the female and male aspects of the individual, to wholeness, to perfection. Each character in the opera is an aspect of the psyche. Koenigsberger is perhaps the first to have commented that the various symbols in the opera relate to each other like a “layer cake”, all of them complementary and all with a common dramatic purpose. Her article is well worth reading for its rich analysis of the opera.

Jocelyn Godwin, in “Layers of Meaning in ‘The Magic Flute’” in The Musical Quarterly 65 (1979) 471-492, reads the opera from both eastern and western esoteric traditions. He ultimately explains the plot in Jungian terms, which he sees connected to the long history of esotericism that also found its way into Freemasonry, and thus into Mozart’s milieu.

Metallurgy and Mining

In the 1980s and 1990s, two scholars from related scientific fields undertook research to learn of relationships between their disciplines and The Magic Flute. I met Andrew Lux first because of his having recognized in the script and stage sets described in the opera’s 1791 libretto a connection to the mining industry, with which he was quite familiar. A Hungarian-born physicist, metallurgist and music enthusiast, Lux, a graduate of the Mining Institute of Technology at Selmec, Hungary, delivered a paper at the 250th anniversary of that institution. In it, he demonstrated that The Magic Flute is penetrated with mineralogical and mining-industry allusions, and further, contains pointed to references to developments in experimental sciences in the circle around Ignaz von Born.

The second scientist who has contributed significantly to my understanding of the opera is Alfred Whittaker, whom Andrew Lux contacted, again because of the science/opera interest. An English geologist now an Honorary Research Associate of the British Geological Survey, Whittaker’s discussions and correspondence with me have reshaped my understanding of many symbols in the opera and my recognition of the role of Karl Ludwig Giesecke as contributor of much of the libretto of The Magic Flute. Whittaker’s “Mineralogy and Magic Flute”, a lecture to the Austrian Mineralogical Society in October 1998, is, I think, a seminal work in exposing the deep connection between 18th-century science and the opera. (Please CLICK here to go to the Kaleidoscope section of this website to find this article in its entirety.) In the course of this article, we learn a great deal not only about mining, chemistry and geological matters but also about the close connection of those sciences to the history of alchemy. Further, we are introduced to the connections between numbers, particularly as symbols in Hermetic language (which includes alchemy) and again in The Magic Flute. Whittaker shows that numbers and the language and the physical processes of alchemy are deeply imbedded in Mozart’s opera. His exposition of the alchemical equivalence of the opera’s plot was a revelation to me, as it must have been to scholars of the generation of M. F. M. van den Berk, whose study I will discuss later in this essay. Four further articles, “Karl Ludwig Giesecke: His Life, Performance and Achievements”, “Karl Ludwig Gieseke: His Albums and His Likely Involvement in the Writing of the Libretto of Mozart’s Opera The Magic Flute”, and “Some Central European Geoscientists of the 18th Century and Their Influence on Mozart’s Music” were published by the Austrian Mineralogical Society in 2001, 2009, and 2010 respectively, and “The Travels and Travails of Sir Charles Lewis Giesecke”, a special publication of the Geological Society of London, 2007. These articles add more than substantially to our knowledge of Giesecke’s life story and, particularly for this essay, his work in theater.

Both Lux and Whittaker present two figures as heavily influential—nay critical, in one case—to creation of The Magic Flute. Ignaz von Born (1742-1791) and Karl Ludwig Giesecke (aka Johann Georg Metzler, 1761-1833) were inextricably entwined in the late 18th century scientific community. Giesecke knew von Born in Vienna and may have assisted him in his amalgamation experiments. Although von Born was not associated with the production of the opera (he was critically ill in his later years), Giesecke was not only an actor and writer for the opera but completely familiar with the scientific milieu of his time. We’ll look at each of these men in some detail next.

Ignaz von Born was the premiere Austrian scientist of the second half of the 18th century, a chemist, metallurgist, and mineralogist who started his career in Hungary, where he was badly burned in a mining accident in 1770. Empress Maria Theresa, Joseph II’s mother, called him to Vienna in 1777 and appointed him the General Director of Mining, Mint and Technical Educational Institutions in Vienna. He served his government exceedingly well by inventing a new technique for amalgamating gold and silver, saving Austria considerable money in the process of extracting those valuable metals; for this achievement Joseph II awarded him the title “Knight of the Realm”, and Mozart composed his cantata Die Maurerfreude, K. 471, for a celebration of the event. Von Born’s knowledge of ores and metallurgy would have extended to the process of alchemy, which was in his time but a step away from modern understanding of physics and chemistry.

Von Born’s scientific interests extended also to botany and zoology, and he generously fostered the dissemination of research of all kinds through international scientific conferences and articles. He was not only a Freemason but, particularly, the Master of the lodge Zur wahren Eintracht (True Harmony) in Vienna, a research lodge, and took interest in broader Masonic matters. His interest in history and letters led him to study ancient mystery religions. It is his article on the mysteries of Isis and Osiris for the first issue of the Journal fűr Freymaurer in 1784 that is generally considered the source of the allusions to those deities in Mozart’s opera seven years later. Von Born was also a member of the Illuminati.

Von Born was such a luminary in the scientific and the masonic community that he was seen by many to be the model for the figure of Sarastro in The Magic Flute. (So also was Joseph II, in other quarters.) His masonic lodge, True Harmony, was the gathering place for the major figures of the day: scientists, writers, musicians, artists, statesmen, clerics, and royalty. The lodge meetings apart from the ritual may have served as a kind of academy at which current scientific or philosophical topics were presented to the brothers. This would be the “work” of a research lodge. The mix of personalities and backgrounds must have been a heady brew, enabling an electric exchange of ideas of many persuasions—constructive, subversive, creative, and more. We know through the work of H. C. Robbins Landon that Mozart and many of his associates in the preparation and performance of The Magic Flute attended this lodge upon occasion. There can be no doubt that in such an environment they were able to be in direct contact with scientific and political ideas, and tap concepts of the Enlightenment culture rampant in Europe of the time.

Von Born’s scientific interests extended also to botany and zoology, and he generously fostered the dissemination of research of all kinds through international scientific conferences and articles. He was not only a Freemason but, particularly, the Master of the lodge Zur wahren Eintracht (True Harmony) in Vienna, a research lodge, and took interest in broader Masonic matters. His interest in history and letters led him to study ancient mystery religions. It is his article on the mysteries of Isis and Osiris for the first issue of the Journal fűr Freymaurer in 1784 that is generally considered the source of the allusions to those deities in Mozart’s opera seven years later. Von Born was also a member of the Illuminati.

Von Born was such a luminary in the scientific and the masonic community that he was seen by many to be the model for the figure of Sarastro in The Magic Flute. (So also was Joseph II, in other quarters.) His masonic lodge, True Harmony, was the gathering place for the major figures of the day: scientists, writers, musicians, artists, statesmen, clerics, and royalty. The lodge meetings apart from the ritual may have served as a kind of academy at which current scientific or philosophical topics were presented to the brothers. This would be the “work” of a research lodge. The mix of personalities and backgrounds must have been a heady brew, enabling an electric exchange of ideas of many persuasions—constructive, subversive, creative, and more. We know through the work of H. C. Robbins Landon that Mozart and many of his associates in the preparation and performance of The Magic Flute attended this lodge upon occasion. There can be no doubt that in such an environment they were able to be in direct contact with scientific and political ideas, and tap concepts of the Enlightenment culture rampant in Europe of the time.

Karl Ludwig Giesecke has the distinction of having stepped aside from a scientific career for a while and participating in what was the less respected world of theater. (Alfred Whittaker’s research provides the basis for this summary of his career relating to The Magic Flute.) He began his university studies in 1781 at Göttingen in law, but then became interested in mineralogy. In the first half of the 1780s he also travelled frequently within Germany, apparently following the career of a young actress. After her death in 1783, he joined the Grossmann theater company in Frankfurt and made his acting debut there. Leaving Frankfurt in 1784, he went to Regensburg and became a writer and actor in the Bock company. Continuing his theatrical career he moved to a number of cities, including Salzburg, Linz, Graz, and finally, in 1789, Vienna, where he became associated with the Theater auf der Wieden, the site of the premiere of The Magic Flute, and which Emanuel Schikaneder would take over. While in Vienna, he may have also found time to assist von Born in his amalgamation experiments. However, Giesecke continued to work with Schikaneder until leaving in 1800, at that time reentering his interrupted scientific career. He would go on to fulfill a distinguished career as a renowned mineralogist, with extensive research in Greenland, and finally as professor of mineralogy at the Royal Dublin Society, Ireland.

Alfred Whittaker’s examination of Giesecke’s part in writing the libretto of The Magic Flute is particularly important to those wishing clarification on the authorship of the libretto. Whittaker located two of five diary albums of Giesecke in which several entries underscore the probability of Giesecke’s having written a good portion of the opera’s libretto. Gieseck was also a participant in the original Vienna production, taking the role of First Slave and, significantly, functioning as stage manager. I examined the printed libretto bearing Giesecke’s name and handwriting. In it he gave titles to several scenes in Act II that capture the style of the scenes in terms such as “Moon theater”, “Sun theater”, “Fire theater”, as if these were symbolic moments. Strangely, he was thinking more symbolically than literally, for the scene which he designated as “Moon theater” has no indication of a moon in its stage directions—the moon is referred to in the text of Monostatos’ aria some 20 scenes earlier. Nevertheless, we must conclude that Giesecke was greatly involved in the preparation of The Magic Flute, and as such certainly shaped its contents, verbally and visually.

Alfred Whittaker’s examination of Giesecke’s part in writing the libretto of The Magic Flute is particularly important to those wishing clarification on the authorship of the libretto. Whittaker located two of five diary albums of Giesecke in which several entries underscore the probability of Giesecke’s having written a good portion of the opera’s libretto. Gieseck was also a participant in the original Vienna production, taking the role of First Slave and, significantly, functioning as stage manager. I examined the printed libretto bearing Giesecke’s name and handwriting. In it he gave titles to several scenes in Act II that capture the style of the scenes in terms such as “Moon theater”, “Sun theater”, “Fire theater”, as if these were symbolic moments. Strangely, he was thinking more symbolically than literally, for the scene which he designated as “Moon theater” has no indication of a moon in its stage directions—the moon is referred to in the text of Monostatos’ aria some 20 scenes earlier. Nevertheless, we must conclude that Giesecke was greatly involved in the preparation of The Magic Flute, and as such certainly shaped its contents, verbally and visually.

Numbers

One characteristic of the work that both von Born and Giesecke engaged in was the attention to numbers; and we should remember that Mozart himself was fascinated with numbers and mathematics throughout his life. Numbers play an interesting role in The Magic Flute. Studies on the issue can be found in Whittaker’s writings, and as well in Joseph Irmen, Mozart: Mitglied geheimer Gesellschaften (Prisca-Verlag, 1998) and in I. Grattan-Guinness, “Counting the Notes: Numerology in the works of Mozart, Especially Die Zauberflöte”, Annals of Science 49, 201-232. I will be preparing a separate essay having to do with numbers in the opera for a later time. However, here is an introduction to several kinds of numerical uses in the opera.

First, of course, are the symbolic references to Freemasonry. The number 3 pervades the opera, as is well known. Three opening chords; three temples; three Ladies serving the Queen of Night; three Boys working in Sarastro’s realm; three slaves; and so on. Even the main key of the opera has three flats in its signature, forming the shape of a triangle. The association with Blue Lodge Masonry is clear: upon being raised in the work of the third degree the candidate becomes a Master Mason. But beyond the third degree of Blue Lodge Masonry are upper degrees in two possible tracks, the York Rite or the Scottish Rite. The eighteenth degree of the Scottish Rite is the “Sovereign Rose-Croix Degree”—the Rose Cross—already in existence and known in Mozart’s time. I will explore more about the Masonic numerical references in a future essay, and the discussion of the Rosicrucians (and thus Rose Cross) occurs later in this essay.

A second kind of numerical use in the opera is symbolic. Hermetic, alchemical, gematria (numerical equivalents to letters), and the Golden Section (.618) are some of the applications, and they are especially relevant to alchemy. Of major importance are the numbers 1 (the mystical unity), 3 (other than the Christian Trinity, a perfect whole having beginning, middle and end, and a combination of the previous two numbers), and 7 (natural phenomena such as moon phases, number of planets and metals of early science), and additives, multiples, and combinations of these.

For instance, the number 3, so important to Freemasonry, is apparent in the many occasions of triadic melody construction and repetitions of chords. In combinations of 3s, we have already seen the use of the number 18, in the reference to the Scottish Rite degree of the Sovereign Rose Croix. This is obviously a multiple of 3 (3 x 3 x 2) and is applied in The Magic Flute in several ways: Sarastro enters in the 18th scene of Act I; there are 18 seats and 18 priests in the conclave at the beginning of Act II; the trials of fire and water occur in the 18th scene of Act II (in which the chorale tune begins in the pick-up to the 18th measure); Tamino’s first measure of singing is in the 18th measure of the opening scene of Act I. This last point may seem pedestrian until we consider that the normal phrase length in Mozart’s time would be in multiples of 4, so we would more likely expect an entrance on measure 16, not 18.

The number 7, likewise, is represented in numerous occurrences in the opera. The seventh eighth-note of the Allegro section of the Overture is marked forte and begins a turning figure, breaking up the repetition of a single pitch; this rhythmic pattern occurs three times in each of the statements of the fugue-like subject before the entrance of the next voice. Moreover, there is a sforzando on the third eighth note of the countersubject! Scales of seven pitches, upward and downward, permeate the opera.

The Golden Section, is a ratio in which a small unit relates to a larger unit as the larger unit relates to the sum of both units, or, a:b::b:(a+b). The percentage is expressed as .618. The Golden Section can be determined in a number of passages in the opera, especially within sections in the Introduction (the opening scene, through the departure of the Three Ladies) and several arias and shorter pieces. For example, in the Queen's first-act aria, there are 103 measures in total; the Golden Section, measure 74, marks the beginning of the Queen's commission to Tamino to rescue Pamina ("Du, du, du wirst sie zu befreien gehen"). In the prayer to Isis and Osiris at the beginning of Act II, for Sorostro and men's chorus, the Golden Section marks the significant moment in which Sarastro refers to the descent to the grave should the candidate fail in his initiation (measure 35 of 56). There are many more instances, all of which would reveal Mozart’s structural and symbolic thinking.

Alchemy

What is alchemy, and how is it relevant to The Magic Flute other than in number symbolism?

The alchemical tradition, which extends far back into antiquity, is often perceived as a form of black magic or at best a pseudo-science which fraudulently claimed to transmute base material into gold or great wealth. But alchemy was, in fact, much more than these fraudulent "puffers'" arts. There was a physical aspect of alchemy, that is, work performed in laboratories, which was on one hand associated with healing, thus an early stage of apothecary science, and on the other hand, allied with metallurgy and chemistry—in other words, it was a stage in the development of the modern physical sciences. In addition, however, in early seventeenth-century northwestern German states, where Lutheran Protestantism flourished, alchemy was also a philosophic art. Its terms for processes and materials were metaphors for stages in spiritual development, and thus associated with theology. In many instances the three aspects—healing, physical science, and spiritual or mystical thought—were interrelated in symbolic terms. The tradition of alchemy was well known in Mozart’s time. Just how well known can be assessed by the fact that Mozart and several of his associates who had collaborated in the creation of The Magic Flute had also collaborated in writing another Singspiel, Der Stein der Weisen oder die Zauberinsel (The Philosopher’s Stone or the Magic Island), with an alchemical plot, in 1790.

What can be said of the hermetic art of alchemy? The desired goals of the Great Work, as it was termed, were the heirosgamos or sacred marriage of the noble king and queen, and the creation of the philosopher’s stone, which conferred immortality. However, the reports and descriptions of the actual processes for achieving these goals were murky at best, presumably to protect the art or craft from insincere practitioners. There were numerous variants in both the order and the listing of the procedures, resulting often in contradictory “recipes” for achieving the perfection of the work.

One recent scholar, M. F. M. van den Berk, has with considerable success shown the connection between the alchemical process and the plot of The Magic Flute by interpreting the characters as physical elements—chemical or metallurgical—and showing how their interaction equates to an alchemical procedure. Here is a summary of the process of the alchemical Great Work, as provided in van den Berk’s The Magic Flute: Die Zauberflöte: An Alchemical Allegory (Brill, 2004), p. 229. I am including van den Berk’s assignments of the process to sections in Mozart’s opera, with my clarifications.

First of all, the main characters’ alchemical roles need to be explained. There are, to begin, three (again!) primary substances—salt, sulfur, and mercury—which are the foundation materials of the Great Work:

Pamina is salt, a solid, non-active fundamental substance that can heal, destroy, give flavor, purify, and is characterized by bitterness and wisdom. Among “planets” she is the moon.

Tamino is sulfur, a volatile burning, corroding, poisonous, foul-smelling substance that is needed to “free up” salt. He is represented by the sun.

Papageno/Papagena (androgynous couple) are mercury, with characteristics of liquid, solid and gas, necessary to amalgamate gold and silver, thus able to purify both metals. Mercury is the mediator between salt and sulfur, enabling the conjunction of the two. Van den Berk states that the combination of Papageno and Papagena constitutes the Rebis (a dual thing), a hermaphrodite, the sublime form of the “Mercury of the philosophers”.

Other substances are also needed.

The Queen’s late husband is the Prime Material (this in conflict with Andrew Lux, who sees the Queen herself as the Prime Material), the raw stuff out of which the salt, sulfur and mercury must be taken. He is the Dead King (Long live the King!), akin to the mortally ill Grail King, or Osiris, or Dionysus, from whose death comes the opportunity for regeneration and life. Often represented as a green lion, he could also be shown as a serpent, or a gray wolf and associated with Saturn, and the metal lead. This is a huge role for a character that does not even appear in the opera!

The Queen of the Night is the Anima Mundi, the soul of the world, Isis, black earth, the universal mother who nurtures all, but eventually will overwhelm and destroy, and thus must be cast off to allow the salt, sulfur and mercury to continue their life.

Sarastro is the alchemist, the magician whose offices make the Great Work, the sacred wedding (the heirosgamos) of Tamino and Pamina, possible. In effecting the Great Work, van den Berk shows, there are three stages of process: Initial marriage (first conjunction) (Tamino seeing the portrait of Pamina? J.E.), which needs to be dissolved, leading to:

Nigredo (blackening) = confusion, chaos. The prime material(s) are extracted from the earth, then represented as falling apart (solution or dissolution), breaking down (putrefaction); bride and groom have a limited (impure) meeting (conjunction) (at the end of Act I, where they meet face to face and are separated, J.E.) and need to die to begin the next process. Act I encompasses the Nigredo.

Albedo (whitening or purification) = repeated cleansing operations. The prime material is subjected to washing, distillation, calcination and other purifying processes. This ends with a second, purer meeting, corresponding to the part of Act II ending just before the Finale (Pamina seeing Tamino and being told that this is the last time they will be separated, J.E.) (N.B.: There is one meeting not accounted for in van den Berk’s schema: when Pamina finds Tamino and he will not speak with her, J. E.).

Rubedo (reddening) = coagulation, or final conjunction. The prime material receives its final set of operations, a repeat of the previous two in compact form, a “final cooking”, corresponding to the trials of fire and water in Act II. Note that the 4 elements, earth, air, fire and water are referenced here, and two mountains in which the trials take place (“sun rock” of fire, “moon rock” of water). In the “bath”, the king and queen have intercourse and fertilize each other [sic]. This is the perfect union, the heirosgamos, which yields the transformation of Mercury into the Child of Wisdom, in the following actions:

Multiplication: Papageno is united with Papagena (who looks like him in all but gender, and they have many, many Papagenos and Papagenas. In this stage one sees the “peacock’s tail”*, the multiple colors that indicate the fulfillment of the operation.

*See the comments on Papageno’s tail below.

Projection: Use of the Philosopher’s Stone to purify other metals. Stage directions for the final scene indicate this process.

Exaltation: Tamino and Pamina celebrated at the end of Act II.

Van den Berk’s analysis, employing one of many versions of how to achieve the Great Work, answers a number of questions about why characters change so radically (the Queen truly becomes evil, Monostatos is cast off, and so on), for their nature must not be understood from the beginning as that of a “normal” individual but rather as alchemical elements affecting and affected by a larger process. Unfortunately, Van den Berk’s writing occasionally misrepresents the libretto. He implies, for example, that Tamino and Pamina, rather than Tamino and Papageno are to be veiled and sent through trials, and says that Sarastro is “worshipped” in the opera as an idol, rather than held up as a hero or wise leader (which I think is closer to the text). He also states that images of Papageno show him with a peacock’s tail, but this is inaccurate: Papageno’s tail in the image at the end of his book is not a peacock’s but rather an eagle’s or at best a parrot’s, lacking the eye typical of the peacock. Where the peacock’s eyed feathers are in evidence are on Papageno’s legs, resembling stockings. Do these details make a difference? Probably only in terms of the degree of care with which his analysis should be read. In the main, however, van den Berk has performed a great service in explaining the alchemical nature of The Magic Flute.

But why go to the trouble to embed alchemy into a popular entertainment? Why and how did the creators of The Magic Flute even lock onto the alchemical theme in the first place?

IV. THE ROSICRUCIAN MOVEMENT, ITS DOCUMENTS AND THE MAGIC FLUTE

Alchemy, the symbolic heart of The Magic Flute, is the language of the hermetic tradition extending into antiquity. A number of philosophers, writers, and artists participated in this tradition, but of greatest importance to understanding Mozart’s opera is the Rosicrucian movement. In Mozart’s time a New Order of the Gold- and Rosy Cross gathered a considerable following, and a number of the nobility with whom Mozart associated were members of the organization. Although it worked in an alchemical symbolism, it is quite different from the earlier, “original” Rosicrucian movement, which, as I will demonstrate, impacted the opera. The 18th-century “new” Rosicrucian organization drew from the earlier Rosicrucians’ documents and in many ways assured that they, and alchemy, were concepts in wide circulation in the second half of the century. But I shall be focusing on the earlier Rosicrucians, and the reason for that will become evident.

In the course of my study of the opera’s music and libretto, a colleague at Cleveland State University introduced me to Frances Yates' remarkable work, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972, and Shambhala, 1978). This book ultimately directed my thinking in a totally new path and opened a door to recognizing a new dimension to the opera, and suggested a purpose until then unexplored for the work. The reading of The Magic Flute which I presented earlier—the opera as a guide to a bloodless social and political reform—is reinforced by parallelisms between the opera's plot and the material of the Rosicrucian documents of the early 17th century, and by the parallelism between the circumstances of that movement and the situation in which, nearly two centuries later, the creators of the opera found themselves. These parallelisms strike me as being so strong and so compelling that I see the Rosicrucian movement and documents as sources for significant portions of the opera's plot and worthy of joining the list of other now-accepted sources for the work.

The suggestion of Rosicrucian connections to the opera was not original to my study. Two 20th-century monographs on The Magic Flute—Jacques Chailley’s Magic Flute, Masonic Opera (tr. H. Weinstock, Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), and Alfons Rosenberg’s Die Zauberflöte, Gesichte und Deutung von Mozart’s Oper (Prestel Verlag, 1972—pointed out that the opera used Rosicrucian symbols and tracts as sources of the alchemical union of Tamino and Pamina, and that these sources were the connection to both mid-eighteenth-century Freemasonry and an organization called the New Order of the Gold- and Rosy Cross. However, neither Chailley nor Rosenberg elaborated further on the Rosicrucian connection to some of the more deeply woven threads in the opera's plot. Upon examining the primary Rosicrucian tracts, I thought it evident that details of the opera’s plot were surely derived from them. I also found that their historical situation was very similar in some respects to the period in which Mozart composed his opera.

The 17th-century Rosicrucians

The term "Rosicrucian" is widely understood to derive from the name of a fictitious and allegorical figure, Christian Rosenkreuz, a German who supposedly lived from 1378 to 1484. A philosopher and deeply religious Christian, he is described as having followed scientific and spiritual paths toward a more perfect knowledge of God and Jesus Christ. His story relates that he travelled to Arabia, Damascus, Egypt, Fez and Spain in his search for learning, and established an association with three other seekers with whom, through example and through study and writing, he might bring about the reformation of the whole world (I found the phrase particularly striking in my evolving understanding of the opera). Eventually this small core grew to eight members who obligated themselves to heal the sick, remain unobtrusive wherever they went, meet together annually on Christmas Day, search for worthy successors, keep their fraternity secret for a century, and travel extensively to increase their own knowledge. After the death of Rosenkreuz and the original members, the younger generations of brothers continued on in a pattern of activities and convocations established by their founder in a private, irregular and unobtrusive manner. A brother's accidental and unexpected discovery of Rosenkreuz's tomb, rich with symbolic construction and contents, signalled to the fraternity that they should make public their origin and their purpose: namely, to instruct, urge and proclaim a world-wide reformation and an era of truth and right (again, a remarkable precedent for Mozart’s opera).

This fictitious Rosenkreuz and his order of reformers were the supposed antecedents to a group of visionaries in the early seventeenth century who, through their publications about Rosenkreuz and his Order, became referred to as Rosicrucians. Illustrations in their writings showed that the Rosicrucians saw their movement or "college" as winged and on wheels, thus "moveable," and their literature referred to them as "invisible," that is, not a publicly-known formal organization. The effect of their writings was broad enough to suggest that their views concretized a rather widespread interest in reform. Although generally localized in Western Germany, the Rosicrucians became a very real source of concern in other parts of Europe as sympathetic publications appeared in those regions. The Thirty Years' War ended their publications and drove the movement underground, but a century or so later, in the mid 1750's, a New Order of the Gold- and Rosy Cross became a formally structured organization attracting many members from among other societies such as Freemasonry and the Illuminati. This new organization took the principal writings of the 17th-century Rosicrucians as their founding documents and continued to espouse the symbolic purposes and language of the earlier movement.

There is some disagreement about the meaning of the name Rosenkreuz. Traditionally it is translated as "rose cross," but there is reason to believe that it originated from a subtler alchemical tradition in which "ros" meant "dew," a solvent of gold, and the cross referred to light. This interpretation points to the fact that the Rosicrucian movement rested largely on the symbolic language of alchemy. The connection of the opera to alchemy is highly significant. It was pointed out in Dorothy Koenigsberger’s “A New Metaphor for The Magic Flute” in European Studies Review, 1975, and explored in great detail in M. F. M. van den Berk’s The Magic Flute: Die Zauberflöte: An Alchemical Allegory in 2004 (which we have already examined in regard to alchemy). We will examine some aspects of this connection in the following section.

Social and Political Impact of the Rosicrucians

Frances Yates showed that the seventeenth‑century Rosicrucian documents touched not only religious life but social and political reform as well. These writings suggest that the "moveable and invisible college" intended particularly to allegorize the 1613 marriage of the Protestant Frederick V, Elector Palatinate (1596-1632), to Elizabeth (1596-1662), daughter of England's James I, as the union of Protestant Europe with Protestant England. In actuality, this union eventually united not only England and north Germany but also, later, Bohemia, where Frederick was elected king, against the extension of Roman Catholic Hapsburg power and the then‑ascendant Counter-reformation within the Catholic Church. In the course of Frederick’s very brief reign as King of Bohemia, events unfolded into the beginning of the vicious, sectarian Thirty Years’ War. When Frederick’s forces were defeated in the Battle of the White Mountain (1630), he took his family to the Netherlands, where they remained for the rest of their lives.

Yates shows that a great many of the intellectuals associated with Frederick's court in Heidelberg were steeped in the symbolism of alchemy and hermeticism with which the Rosicrucian literature abounds, and these figures were strongly associated with the Rosicrucian movement. Yates suggests that the marriage of Frederick and Elizabeth provided for this circle the living model of alchemical unity which otherwise would have been merely an abstract mystical symbol of the Rosicrucian's religious and political aspirations.

The Rosicrucian Documents

The seventeenth-century Rosicrucian movement produced overt evidence of its existence from about 1610 through 1623 in a group of publications describing the origins and philosophy of the order. In several of the documents there was a clear attempt through symbolic language both to articulate and to encourage a spiritual awakening in Europe, especially Protestant Europe, in an effort to effect a return to a simpler, more heartfelt practice of Christ's teachings and to counteract the secularization of the European community at large.

The principal Rosicrucian documents which give the central myth and symbolism of the movement are these:

Fama Fraternitatis (The Story of the Fraternity), 1614, which tells the life history of Christian Rosenkreuz and the founding of the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross by his followers;

Confessio Fraternitatis (The Confession or Creed of the Fraternity), 1615, which gives the ideals of the Brotherhood;

Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosenkreuz (the Chemical—i.e., Alchemical—Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz), 1616, which recounts Christian Rosenkreuz's experiences at a seven‑day festival celebrating the wedding of a royal couple.

Additionally, Radtichs Brotofferr's Elucidarius Major, oder Erleuchterunge [sic] über die Reformation der ganzten weiten Welt, 1616/1618 (The Great Elucidations or the Enlightenment concerning the Reformation of the Whole Wide World) is the commentary on the Chemical Wedding.

Many scholars believe the author of the first three documents was Johann Valentin Andreae (1586-1654), a Lutheran pastor and theologian, and grandson of the noted theologian Jakob Andreae. (With the beginning of the Thirty Years' War in 1618, Andreae published what many historians consider to be recantations of his earlier enthusiasm for Rosicrucian ideals). These works, together with Andreae's utopian book, Christianopolis, 1624, and Christopher Kotter's Lux in Tenebris, written probably in 1624 but published in 1675, urging Frederick's Protestant forces not to lose courage after their defeats, constitute the main bulk of literature in the Rosicrucian movement; there were also numerous open letters either praising or condemning the principles and philosophy propounded in the Rosenkreuz adventures.

I found the early seventeenth-century Rosicrucian documents to be far more significant to the opera's plot and libretto than is generally recognized. These documents and the Rosicrucian movement which they represent account for a number of important details in the opera that are not touched by previously known sources, although recent scholars like van den Berk are now recognizing them. Among these details are the intricate history of Pamina's abduction and her trials at the hands of Monostatos; Papagena's peculiar appearance as an old woman throughout most of her stage activity; and a host of clearly symbolic details throughout the opera.

The most extensive points of correspondence from this body of literature to The Magic Flute come from the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz and the commentary on it, the Great Elucidation, as well as the somewhat later Christianopolis. I would like to show you the full range of correspondences that I have located, but in the interest of a more manageable length for this essay I will concentrate on a few which concern primarily the Chemical Wedding and, secondarily, the Great Elucidation. For a fuller exploration of the relationship between the Rosicrucian documents and The Magic Flute, please see my Cultural Context of Mozart’s “Magic Flute, Vol. I.

The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz

The Chemical Wedding contains two extensive threads that occur in the opera: the concept or vision of an alchemical union or wedding, and a story line that has a parallel in Pamina's experiences in the opera. There are as well several other less extensive but very clear correlations to the plot and stage details, many of which concern Papageno and Papagena. That The Magic Flute as a whole is an alchemical metaphor has already been well established through the work of Koenigsberger and van den Berk, especially; the Chemical Wedding's unquestioned use of the alchemical process to bring about the heirosgamos or sacred wedding makes it a particularly strong paradigm for the opera's theme of unifying Tamino and Pamina, and, in parody, Papageno and Papagena.

However, the alchemical symbolism goes far deeper than the obvious heirosgamos, and we need to examine some details.

The Chemical Wedding is narrated by Christian Rosenkreuz, who has been summoned by a mysterious invitation to be a guest in the week‑long celebration of festivities around the wedding of a young royal couple. The invitation itself contains a curious reference to three temples on a mountain, the vantage point from which all of the wedding events will be seen. Rosenkreuz dons his distinctive attire: a white coat, a red ribbon draping from his shoulder across his body, and a hat decorated with four red roses. He finds the proper path to the royal palace and passes into the grounds through several portals, one of which is guarded by a lion. Along with the other guests he is shown the magnificent rooms, library, grounds, and a lion fountain in a garden, and eventually taken on a tour of an underground vault lighted by glowing red gems and containing a sepulchre on which are unusual inscriptions. On the Sixth Day, he and the other guests observe the alchemical creation of life; in this case the new being is a bird with many-colored feathers. On the Seventh Day before their departure for their homes, he and the other guests are made Knights of the Golden Stone, celebrated with procession and pomp, and given a book of rules which the Knights of this order must observe. Rosenkreuz, however, is not permitted to go home but must, rather, take over the duties of the porter at the gate, in punishment for letting his curiosity lead him to forbidden rooms in the palace during the Fifth Day. His release is implied in a postscript explaining that in the narration contained in several lost leaves of the manuscript, Rosenkreuz finally arrived home.

The union of the royal couple in the Chemical Wedding is, of course, the foremost point which this fable has in common with The Magic Flute, in which the union of Prince Tamino with Princess Pamina is the crux of the plot. But other points of similarity are evident, from even the most superficial observation, to those who know the opera’s story and stage directions. The three temples in which the royal wedding will occur in Andreae's work are mirrored in the three temples in Sarastro's realm (I, xv). The lion that Rosenkreuz meets in the entry to the palace grounds has a parallel in the lions which draw Sarastro's chariot (I, xviii) and which threaten Papageno during the trials (II, xix). The underground vault with its glowing gems suggests the sparkling cavern out of which the Queen of the Night first appears (I, vi), but its function as a tomb is more closely allied with the underground chambers in which Tamino and Papageno must reflect in their trials (II, ii-vi). The multicolored alchemical bird created in the Sixth Day suggests Papageno himself, who is a birdcatcher camouflaged by being covered with feathers (I, ii). Even though these points of commonality lie on the surface of the works, however, they are far from insignificant. They represent principal themes and images which are central to both works. But in addition to these relatively overt points, there are others which provide even more detailed links between the two works and require closer examination.

The explicit duration of the Chemical Wedding's celebration is very important, for, as the Great Elucidation points out, the week‑long festival is a clear and unmistakable allusion to the Biblical creation of the world in seven days. As I have stated earlier, The Magic Flute has as a primary theme the regeneration of the individual and society, cast as an image of a new Eden. But the Biblical creation story has even more relation to the opera.

Each day of the Chemical Wedding has its own unique imagery for paralleling the alchemical process symbolizing the Biblical creation. However, the fourth day—the central day—is exceptionally important. In the Bible, the fourth day of creation has significant symbols: the separation of night from day, the creation of the stars, the creation of greater and lesser lights to rule day and the night, and to mark seasons and years. The Biblical night-day dichotomy and cyclic changes echo the Light vs. Darkness theme in The Magic Flute's libretto, and very soon after the opera’s premiere these were recognized as important to the opera's symbolism.

But in addition, the specific events of the fourth day in the Chemical Wedding are particularly significant with regard to The Magic Flute. The day's events fall into three parts: a seven‑act play, termed a "comedy," performed by students for the benefit of the court and guests, and the pre‑ and post‑performance actions of Rosenkreuz and his associates in the royal court in relation to the bride‑ and groom‑to‑be. These parts of the fourth-day narration contain information which we can trace in The Magic Flute.