- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

Motet

A Few Little Words About the Motet,

or,

An Anthem by Any Other Name…

By Judith Eckelmeyer

A motet is likely to show up on any vocal concert. It needn’t even be an “early music” concert. Most of the time the audience will realize that with the motet they are hearing a piece of sacred music, especially if the text is in Latin. But how many listeners will realize the deep dark secret about motets: that there was a time when the motet was a secular work, participating in a kind of counter-culture that raked the establishment over the coals?

And how many would know why the motet got its name?

Let’s look at this genre more closely to answer these questions, and to find out why the term “anthem” even might be mentioned in the same breath with the motet.

And how many would know why the motet got its name?

Let’s look at this genre more closely to answer these questions, and to find out why the term “anthem” even might be mentioned in the same breath with the motet.

Beginnings:

The term motet means “little word”. This term originated within a very specific situation that developed in sacred music of the 13th century. Here’s how it happened:

The motet’s existence is rooted in plainchant, the melodic setting of liturgical text of the Roman Catholic Church through the Medieval Era. Normally, plainchant is sung as a single, unaccompanied melody, in Latin. Its notes had no specifically regulated durational (rhythmic) values but were subtly shaped by the accents of the text.

The term motet means “little word”. This term originated within a very specific situation that developed in sacred music of the 13th century. Here’s how it happened:

The motet’s existence is rooted in plainchant, the melodic setting of liturgical text of the Roman Catholic Church through the Medieval Era. Normally, plainchant is sung as a single, unaccompanied melody, in Latin. Its notes had no specifically regulated durational (rhythmic) values but were subtly shaped by the accents of the text.

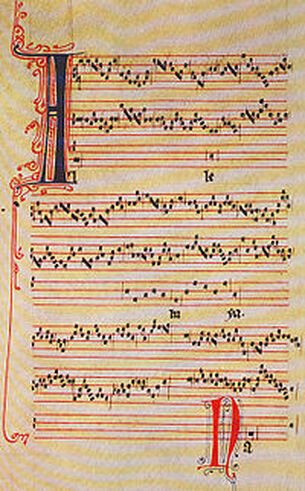

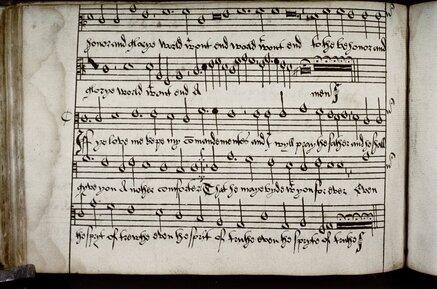

Music of the Middle Ages

An Anthology for Performance and Study by David Fenwick Wilson

An Anthology for Performance and Study by David Fenwick Wilson

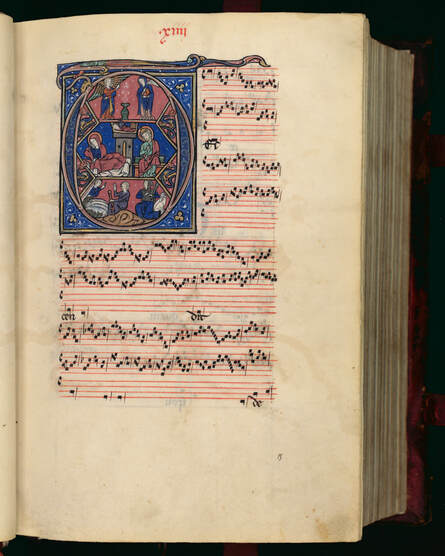

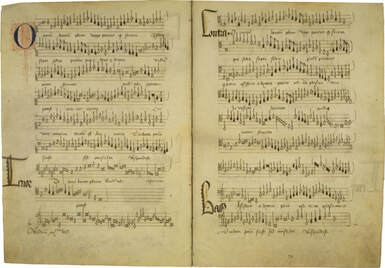

As far as written records attest, plainchant prevailed in its pristine style until the ninth century, when a couple of documents from what is now France show us samples of music for two simultaneous voices. One voice is the plainchant, the other has the same text as the plainchant but a different melody. Both texts have one note per syllable and move exactly together. This is the earliest known polyphony (more than one melody performed at the same time), and it is called organum. In organum, there is always one vocal line with plainchant while at the same time additional voice parts sing the same text to different, newly-composed melodies.

Graduel D'Alienor De Bretagne (Gradual of Eleanor of Brittany)

Plain-chant et polyphonies des XII & XIV siecles

Ensemble Organum, Marcel Peres

Plain-chant et polyphonies des XII & XIV siecles

Ensemble Organum, Marcel Peres

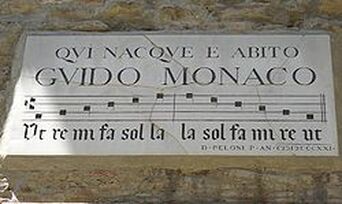

Consider for a moment the implications of more than one melody line in simultaneous performance. In the Medieval Era, only certain intervals between the pitches were considered legitimate, or “consonant”, based on concepts of “perfection”—the only value considered appropriate for sacred music. If one were to compose organum, one would have had to assure that the correct sounds occurred at the proper time to achieve “perfect” intervals. So, some system of symbols had to be invented to convey both pitch and its duration. Symbols for early types of organum were imprecise. By about 1000 a monk in Italy, Guido of Arezzo, had invented not only a 4-line staff on which pitches could be precisely specified, but also a system of reading them at sight. This technological advance must have been a great relief for those who otherwise would have to learn a huge body of music by rote!

However, Guido’s ingenious inventions went only so far. They addressed melodic information, not duration of notes. More work was needed.

By the late 12th and early 13th centuries, concurrent with the construction of early Gothic cathedrals and the establishment of the first universities on the continent, organum had achieved a level of some sophistication. One major center of organum composition was around the Cathedral of Paris and its successor Notre Dame, so the organa (plural of organum) written there were said to be of the Notre Dame “school”. In Notre Dame organa, the plainchant was the foundation—and thus the lowest vocal part—against which one, and then two or three additional melodies occurred above it. Because the lowest part contained or “held” the liturgical chant (melody and text), it was termed the “tenor”, from the Latin tenere, “to hold”. (How the term “tenor” came to designate a voice part in a choral environment is another story too long for this essay.) When the plainchant melody had only one note per syllable (a style called syllabic), the note for each syllable was held out, like a drone, while the additional voice parts above sang many more notes for that syllable (a style called melismatic). All of the voice parts were simultaneously performing the Latin liturgical text provided in the plainchant. The pace of the text was relatively slow because of the number of notes that had to be sung above the plainchant notes.

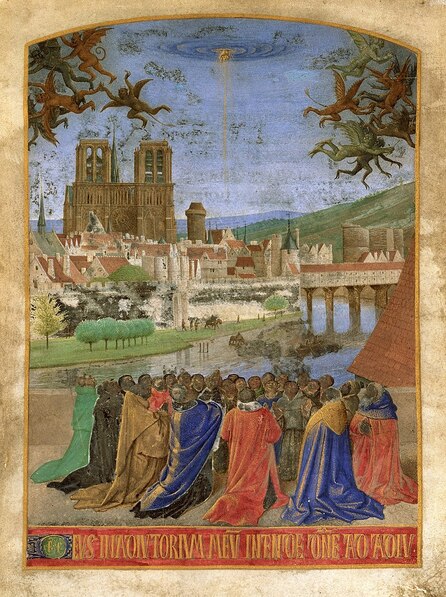

By the late 12th and early 13th centuries, concurrent with the construction of early Gothic cathedrals and the establishment of the first universities on the continent, organum had achieved a level of some sophistication. One major center of organum composition was around the Cathedral of Paris and its successor Notre Dame, so the organa (plural of organum) written there were said to be of the Notre Dame “school”. In Notre Dame organa, the plainchant was the foundation—and thus the lowest vocal part—against which one, and then two or three additional melodies occurred above it. Because the lowest part contained or “held” the liturgical chant (melody and text), it was termed the “tenor”, from the Latin tenere, “to hold”. (How the term “tenor” came to designate a voice part in a choral environment is another story too long for this essay.) When the plainchant melody had only one note per syllable (a style called syllabic), the note for each syllable was held out, like a drone, while the additional voice parts above sang many more notes for that syllable (a style called melismatic). All of the voice parts were simultaneously performing the Latin liturgical text provided in the plainchant. The pace of the text was relatively slow because of the number of notes that had to be sung above the plainchant notes.

Let’s think a minute about performing Notre Dame organum: Just what was the pace of those notes in the upper voices? And what happened when the plainchant melody became melismatic itself, with lots of notes on one syllable that just kept on going? There would be no new syllables to use as guides for aligning sounds! These problems were going to require solutions.

With all those different melodies going on at once, it became critical to invent a way to identify not just pitch but rhythmic values as well, so all the voices would line up properly in a “consonance”. (Did you remember that “consonance” occurred with only “perfect” intervals? None of this “Ooh, I like that sound” for Medieval theorists!) In a word, performers needed some way to know “how long to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em” (to paraphrase a more recent song) so they would always conform to the proper “perfect” harmonic structures—unquestionably necessary for a culture under the power of the Church. What to do?

The solution: Notre Dame composers used note shapes and groupings of notes to represent durational values as well as pitch. Taking their cue from the university’s current scholastic interest in ancient Greek poetic theory, they devised notation that produced Greek poetic rhythms, such as iambic and trochaic. Because rhythm prior to this time was not exact, to impose a specification on the duration of sounds was a radical development.

The rhythms of Notre Dame organum were quite simple by our standards, being based on groupings of three units of duration in keeping with the theological concept of the Trinity. They were particularly necessary in passages where the plainchant had a melisma—many notes on one syllable. To accommodate this melisma, the tenor stopped holding its notes out and moved relatively quickly, in the newly devised rhythmic structures, mimicking the movement of the upper voices. All the voice parts were then singing the same liturgical text with rhythmically similar motion. This produced a note-for-note structure that sounded more like chordal harmony than voice parts over a drone.

With all those different melodies going on at once, it became critical to invent a way to identify not just pitch but rhythmic values as well, so all the voices would line up properly in a “consonance”. (Did you remember that “consonance” occurred with only “perfect” intervals? None of this “Ooh, I like that sound” for Medieval theorists!) In a word, performers needed some way to know “how long to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em” (to paraphrase a more recent song) so they would always conform to the proper “perfect” harmonic structures—unquestionably necessary for a culture under the power of the Church. What to do?

The solution: Notre Dame composers used note shapes and groupings of notes to represent durational values as well as pitch. Taking their cue from the university’s current scholastic interest in ancient Greek poetic theory, they devised notation that produced Greek poetic rhythms, such as iambic and trochaic. Because rhythm prior to this time was not exact, to impose a specification on the duration of sounds was a radical development.

The rhythms of Notre Dame organum were quite simple by our standards, being based on groupings of three units of duration in keeping with the theological concept of the Trinity. They were particularly necessary in passages where the plainchant had a melisma—many notes on one syllable. To accommodate this melisma, the tenor stopped holding its notes out and moved relatively quickly, in the newly devised rhythmic structures, mimicking the movement of the upper voices. All the voice parts were then singing the same liturgical text with rhythmically similar motion. This produced a note-for-note structure that sounded more like chordal harmony than voice parts over a drone.

A brief note on composers:

Until about the 12th century all the sacred music we know was prepared by anonymous musicians in religious communities. By the 12th and 13th centuries we begin to see names associated with musical composition. We know two of the Notre Dame composers by name: Leoninus (Léonin), who was working from the 1150s to about 1201, and Perotinus (Pérotin), working in the late 1100s and early 1200s. Both men created many organa; those of Léonin formed a collection called “The Great Book of Polyphony”. In the works of Léonin and Pérotin we can see the vigor of their creativity as they produce bigger and more complex works over their careers.

Until about the 12th century all the sacred music we know was prepared by anonymous musicians in religious communities. By the 12th and 13th centuries we begin to see names associated with musical composition. We know two of the Notre Dame composers by name: Leoninus (Léonin), who was working from the 1150s to about 1201, and Perotinus (Pérotin), working in the late 1100s and early 1200s. Both men created many organa; those of Léonin formed a collection called “The Great Book of Polyphony”. In the works of Léonin and Pérotin we can see the vigor of their creativity as they produce bigger and more complex works over their careers.

Ensemble Gilles Binchois, Dominique Vellard, dir. Le Chant des Cathédrales - Ecole de Notre Dame de Paris

Anne-Marie Lablaude, Brigitte Lesne, Catherine Schroeder, Gerd Türk, Dominique Vellard, Emmanuel Bonnardot, Philippe Balloy, Willem de Waal

Anne-Marie Lablaude, Brigitte Lesne, Catherine Schroeder, Gerd Türk, Dominique Vellard, Emmanuel Bonnardot, Philippe Balloy, Willem de Waal

The birth of the motet:

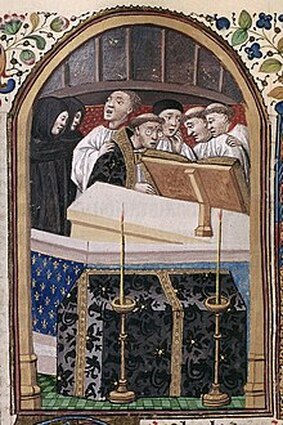

As noted earlier, the Notre Dame “school” of composers encountered passages in organum in which not only the upper voice(s) but the tenor as well moved quickly, more or less together, and specific patterns of duration ensured that appropriate pitches occurred together. Such a passage is called a clausula. But remember: all of the voices of the organum, including the clausula, were still performing the same text at the same time.

The clausula is the crux of our history here, for it is the well-spring of the motet. It was from that (often brief) passage that a new genre was born.

As is often the case, the musicians of the time couldn’t leave well enough alone but decided to ornament the ornament, so to speak. Those new melodies riding above the plainchant, which were themselves ornaments to the liturgical chant, needed something, they thought. And that something was--text! In the earliest instances, the new text applied to the melodies above the liturgical chant line in the tenor made reference or allusion to the words of the liturgy. They were not part of the liturgy but were sacred poetry, intended to add a reflection on the tenor’s text. These new texts, being commentary on the liturgy, were thus called the “little text”, or the “little word”, the old- French term for which was (you guessed it!): motet.

Believe it or not, the texts of the upper voices began to employ vernacular texts rather than the liturgical language of Latin which was still present in the tenor. Texts in French became increasingly common for the upper voices. Moreover, these French texts may well have been sung at the same time as the liturgical text in the tenor! In any case, creating new texts to fit within the clausula became a raging fad by the end of the 13th century—so much so that composers began to lift the clausula out of its original organum setting in order to create more and more of the “motet” segments as independent pieces of music. Thus the motet achieved its status as a new genre.

Perhaps the confusion of all those different languages and words happening simultaneously bothered folks, or perhaps the listeners needed to hear the tenor’s plainchant melody more clearly. Or perhaps singers of the tenorpart couldn’t sustain the longer notes that by the 14th century became the norm for the plainchant line. In any case, the slow-moving tenor “voice” became an instrumental part, typically performed by a string instrument, which didn’t need to breathe. Meanwhile, the upper voices with their different texts were still sung, and still produced a jumble of words.

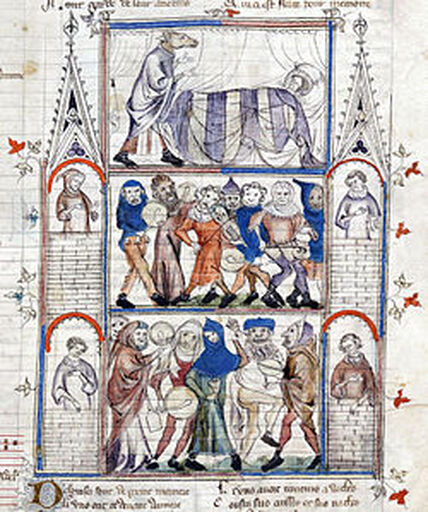

As long as the motet’s upper parts had sacred poetry to supplement the liturgical material in the tenor, it could be called a sacred work. However, by the end of the 13th and during the 14th century there was a massive trend toward secular uses for the genre. The tenor retained a sacred chant melody, albeit played by an instrument so the text was not in evidence. However, the upper parts began to have rather explicitly social, political, or amorous poetry, making them secular works. An entire collection of such secular motets, the Roman de Fauvel (ca. 1317), blatantly criticized corruption in society and in the Church.

Two major composers of secular 14th-century motets were Philippe de Vitry (1291-1361) and Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377). As a result of the development of shorter note values and ways to notate them, their works included a remarkable complexity of rhythmic values. The new rhythms often created dance-like syncopations, showing unquestionably worldly influences. Further, these composers used not only three-part divisions of note values but two-part divisions as well, obscuring the rhythmic allusion to the Trinity. Repetitions of rhythm patterns and short melodies usually in the tenor of Machaut’s and de Vitry’s motets formed a highly organized compositional structure called isorhythm. Harmonic progressions that distinguish their music, and indeed most of the music of this period, often sounded dissonant because they were still trying to adhere in some ways to the theological concept of “perfection” while juggling three or four very active voice parts. Theorists thought the complicated and secularized style of the time was so different from what had been the norm a mere 50 to 70 years earlier that they termed it the “Ars Nova”, or “New Art”, to distinguish it from the simpler earlier style, which they called in retrospect the “Ars Antiqua” (“Ancient Art”).

The motet gets a facelift:

Quietly working away in the British Isles, composers were creating music with a completely different sound from that of continental composers’ music. The melodies and rhythms were much simpler, and the harmonies were “sweeter”, favoring intervals we call thirds and sixths rather than the dogmatic “perfect” intervals of the continental style. Examples of polyphony, based on England’s Sarum rite, contain triadic or three-pitch harmonies that sound like the common harmonic style of our own time. Even simple folk music and the many religious carols participated in this sound. This tradition informed the work of a significant composer, John Dunstable (or Dunstaple) (1390-1453), whose impact on the music of the continent would change the course of motet composition.

Quietly working away in the British Isles, composers were creating music with a completely different sound from that of continental composers’ music. The melodies and rhythms were much simpler, and the harmonies were “sweeter”, favoring intervals we call thirds and sixths rather than the dogmatic “perfect” intervals of the continental style. Examples of polyphony, based on England’s Sarum rite, contain triadic or three-pitch harmonies that sound like the common harmonic style of our own time. Even simple folk music and the many religious carols participated in this sound. This tradition informed the work of a significant composer, John Dunstable (or Dunstaple) (1390-1453), whose impact on the music of the continent would change the course of motet composition.

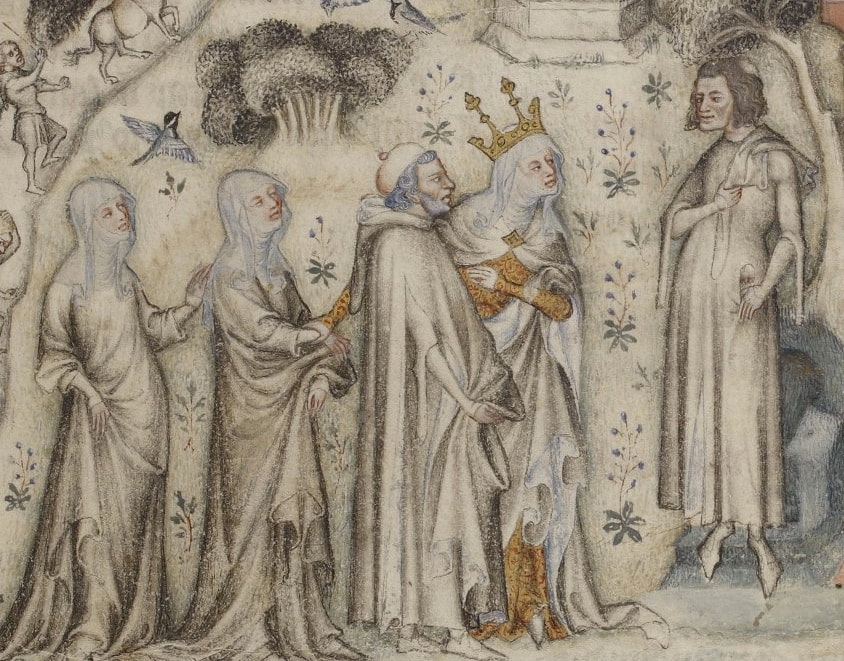

A brief bit of political history is needed here. By Dunstable’s time, there was a war in progress in the territory we know as France and Belgium. The problem was that England and France both laid claim to certain portions of the area. In this argument, the territory of Burgundy was an ally of England. This is the famous Hundred Years’ War, which eventually ended with England ceding her claims and letting France get on with her business. (Joan of Arc assisted in turning the tide in favor of the French.) In the course of this long and complicated conflict, an Englishman, John, the Duke of Bedford, found it necessary to go to his property in Rouen in the region of Burgundy for extended periods of time. Among the duke’s entourage was none other than John Dunstable, who, historians speculate, accompanied his lord.

Dunstable was known as a mathematician and astronomer on the Continent; but more to the point, elements of his musical style began to appear in the music of a Burgundian composer, Guillaume Du Fay (1397-1474). We think that Dunstable actually had come to France, and we can only speculate whether he in fact met Du Fay, but it appears that Du Fay heard Dunstable’s music and really liked it. The difference in the sound of Dunstable’s music from that of the Burgundian composers was so distinct that a 15th-century French poet, Martin le Franc, termed it the contenance angloise, or English quality.

When Dunstable set music to sacred texts (other than the Mass), he usually wrote for only three voice parts. Many of these works have no reference to a plainchant melody, and there is only one text, in Latin, that all the voices sing at the same time. Nevertheless, these sacred pieces are generally placed under the umbrella term “motet” today. This single-text style of writing motets became the norm from Dunstable’s time on.

Dunstable's "Veni Creator Spiritus"

Pro Cantione Antiqua Hamburger

Blaserkreis fur alte Musik / Bruno Turner

Pro Cantione Antiqua Hamburger

Blaserkreis fur alte Musik / Bruno Turner

There are a few notable throwbacks in which multiple texts occur. One such is Du Fay’s famous “Nuper rosarum flores”, an old-fashioned chant-based, four-voice, multi-texted isorhythmic motet composed for the consecration of the dome of Florence’s Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in 1436. For the most part, however, composers embraced the new concept of writing polyphonic sacred pieces in Latin, with all voices singing the same text, and all voice parts newly composed (i.e., not based on a chant melody).

Dufay's "Ave Maris Stella"

Pomerium | Alexander Blachly, conductor

Pomerium | Alexander Blachly, conductor

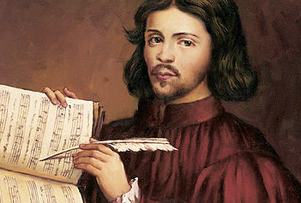

The successive generations of composers after Dunstable and Du Fay found this new style of motet highly adaptable to their interests in technical invention. In the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries composers from Burgundy, northern France, and Belgium greatly advanced the motet. Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1410-c. 1497), Jacob Obrecht (c. 1450-1505), Loyset Compère (c. 1445-1518), and Josquin des Pres (c. 1440-1521) were especially important in bringing the motet to its maturity in the Renaissance. Josquin, in particular, was the “master of the notes”, as Martin Luther commented. His motets display a wide range of techniques that became standards throughout the era. These techniques, including canonic devices (using one melody as the origin for other voice parts), imitative counterpoint (subsequent entries of voices using the same beginning material as the first voice), and pictorialization of the text (in which the music demonstrates words in the text, such as “rising” or “falling”), are just some of the exciting ways composers played with music in motets. The a cappella (unaccompanied) motets of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594) are perhaps the apex of the genre in the late Renaissance, although many other composers of all nations were creating marvelous examples.

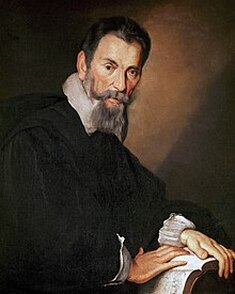

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries composers adapted the motet to current musical tastes. Certainly Giovanni Gabrieli’s (1553-1612) motets for up to four separate groups of voices and instruments, for the opulent environment of Venice’s St. Mark’s Basilica, are among the most aurally sumptuous and exciting in motet history. Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), although writing his early motets in the late Renaissance style, made a transition to a new style later named “Baroque”. These early seventeenth-century works were for varying combinations of soloists and accompanying instruments with continuo, and he called them not motets but rather “concertos”.

In France under Louis XIV, Henry Du Mont (1610-1684), Pierre Robert (1618-1699), Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), Marc-Antoine Charpentier (c. 1645 to 1650-1704), and Michel-Richard de Lalande (1657-1726) introduced and developed the tradition of the grand motet. This was a long and lavish work in Latin, organized in sections that changed between vocal solos, small and large choirs, or combinations of singers, accompanied by a five-part orchestra.

|

No image of Pierre Robert available

|

Robert's "Nolite me considerare"

La Chapelle Royale du Château de Versailles Chantal Santon(dessus), Paul-Antoine Bénos(contre-tenor chantre) Erwin Aros (haute-contre), Jean-François Novelli (taille), Vlad Crosman (basse-taille chantre), Arnaud Marzorati (basse-taille), Pierre Beller ( basse chantre) |

|

De Lalande's "Te Deum"

Le Poème Harmonique, Ensemble Aedes, Vincent Dumestre Emmanuelle de Negri, soprano | Dagmar Šaškova, soprano | Sean Clayton, haute-contre | Cyril Auvity, tenor |

Eventually, beginning with the Protestant Reformation, Latin text would be avoided in favor of a vernacular. For instance, Heinrich Schütz wrote hundreds of motets in German; J. S. Bach wrote six extended motets in German; and numerous English composers of the 16th and 17th centuries wrote English-language motets. But no matter the language, still usually only one text would be performed at a time.

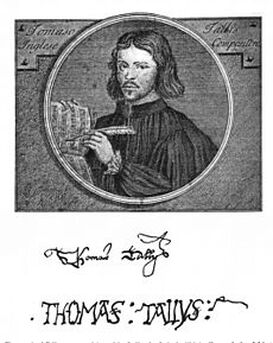

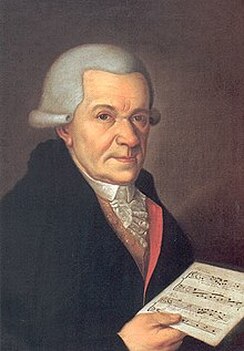

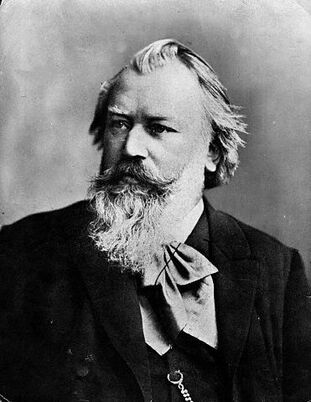

Over the course of the next five hundred years, virtually every major composer would put his hand to the genre of the motet. Some of the more well-known composers (other than those mentioned above) and the languages of their motets are Thomas Tallis (1505-1585—Latin and English), William Byrd (1543-1623—primarily Latin); Michael Haydn (1737-1803—Latin); W. A. Mozart (1756-1791—Latin); Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847—German and English); Anton Bruckner (1824-1896—Latin and a very few German); Johannes Brahms (1833-1897—about a half dozen in German and several in Latin); and Francis Poulenc (1899-1963—Latin).

The Anthem appears:

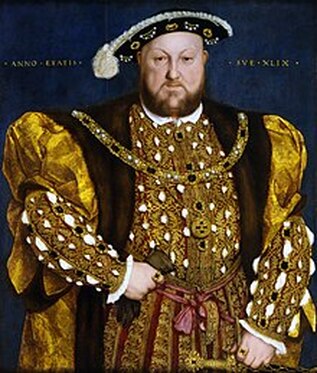

The term “anthem” goes back to the 11th century as a variant on the term “antiphon”, but the genre of “anthem” came to prominence in the sixteenth century with the birth of the Church of England, or the Anglican Church. Henry VIII’s rejection of the authority of the Pope (finalized in 1536) opened the door to the new denomination. Although technically fostering a Protestant sect, Henry permitted Latin in the service. Among the works favored for use were votive antiphons—settings of Latin prayer texts that were accessible to the ordinary person for private devotions. These are the precursors to the later “anthem”.

The term “anthem” goes back to the 11th century as a variant on the term “antiphon”, but the genre of “anthem” came to prominence in the sixteenth century with the birth of the Church of England, or the Anglican Church. Henry VIII’s rejection of the authority of the Pope (finalized in 1536) opened the door to the new denomination. Although technically fostering a Protestant sect, Henry permitted Latin in the service. Among the works favored for use were votive antiphons—settings of Latin prayer texts that were accessible to the ordinary person for private devotions. These are the precursors to the later “anthem”.

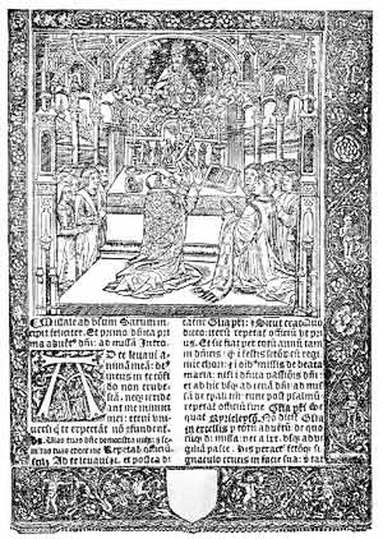

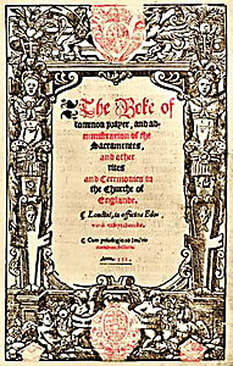

Henry’s son Edward VI (reigned 1547-1553) insisted on a real change from Roman Catholicism. He established, with the 1549 Act of Uniformity of Service and Administration of the Sacraments throughout the Realm, the obligation to use the Book of Common Prayer. English, not Latin, was the only legal language for the Church of England. Poets and composers (many of them anonymous) hastened to supply new “sober, discreet” works in English for the prescribed services: Matins (Morning Prayer), Evensong (Vespers) and “the Lord’s Supper” or Eucharist.

A manuscript collection called the Wanley Part Books or Wanley Manuscripts from about 1549 shows English liturgy in this modest style. (They are called “part books” because only one voice part is given in each volume; four singers are required to sing from the four volumes to provide the complete musical texture.) Among the new music especially for Matins and Evensong were sacred devotional works that, had they been in Latin, would have been called “motets”, but now were termed “anthems”. Most of them were for four male voice parts in very simple note-against-note counterpoint, with one note to a syllable so that the words could be heard clearly.

Among the composers of these early English anthems are Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585), Christopher Tye (c. 1505-1572), John Taverner (c. 1490-1545), Richard Farrant (c. 1525 to 1530-1580), and John Sheppard (or Shepherd) (c. 1515-1559 or 1560).

|

No image of Christopher Tye available

|

Tye's "Laudate Nomen Domini"

The Cantata Choir of Canterbury Christ Church University, Directed by Prof Grenville Hancox |

|

No image of Richard Farrant available

|

Farrant's "Hide Not Thou Thy Face"

Clare College Chapel Choir, Timothy Brown, director |

|

No image of John Sheppard available

|

Sheppard's "Libera nos I & II"

The Sixteen, Harry Christophers, director |

A new style of anthem appeared in the middle of the 16th century; this was the “verse anthem”. In it, passages for one or more soloists accompanied by an instrument (usually organ) alternated with passages for a full choir.

By the end of the 16th century the Anglican anthem had the characteristics of the sophisticated motets of the continent. Written with English text for an entire unaccompanied choir, these contrapuntal works were called “full anthems” as distinguished from the “verse anthem”.

Over the course of the next century, the anthem developed into a much grander work, frequently in several movements and performed by one or more soloists and full choir accompanied by an orchestra of strings and winds, and with an organ continuo. Composers such as Henry Purcell (1659-1695) and George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) wrote such anthems for grand occasions like coronations or royal funerals, or just for the use of the nobility for their worship. At the end of the 18th- and beginning of the 19th centuries, Thomas Attwood (1765-1838), an English pupil of Mozart, contributed 18 published anthems and other sacred music for the Anglican community.

By the end of the 16th century the Anglican anthem had the characteristics of the sophisticated motets of the continent. Written with English text for an entire unaccompanied choir, these contrapuntal works were called “full anthems” as distinguished from the “verse anthem”.

Over the course of the next century, the anthem developed into a much grander work, frequently in several movements and performed by one or more soloists and full choir accompanied by an orchestra of strings and winds, and with an organ continuo. Composers such as Henry Purcell (1659-1695) and George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) wrote such anthems for grand occasions like coronations or royal funerals, or just for the use of the nobility for their worship. At the end of the 18th- and beginning of the 19th centuries, Thomas Attwood (1765-1838), an English pupil of Mozart, contributed 18 published anthems and other sacred music for the Anglican community.

Anthems also came into the musical practice of other denominations besides the Anglican Church. John Wesley (1703-1791) brought the influence of Anglican practice into the young Methodist church he founded, and his nephews Charles (1757-1834) and Samuel (1766-1837) contributed enormously to the anthem (and hymn) literature.

In the decades before and after America’s War of Independence, self-taught composers such as William Billings (1746-1800) in the Boston area wrote anthems for the Congregational Church using both sacred and nationalistic poetry. He used a variety of chordal writing, rough “fuging” (canonic or imitative) techniques, simple harmonies, and unsophisticated forms. John Antes (1740-1811), a Moravian pastor and one of a number of Moravian composers, was more musically educated than Billings. His beautiful anthems, with accompaniments of strings and sometimes winds, reveal the influence of the mid-18th-century German heritage of the Moravian community.

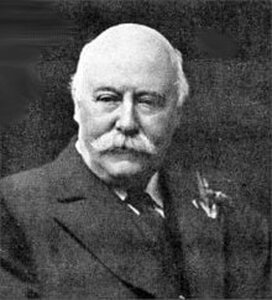

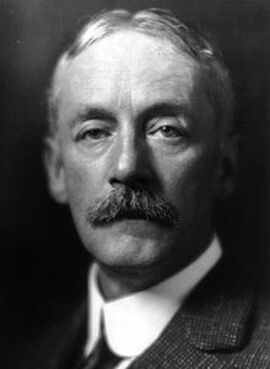

The nineteenth century began with what most historians consider a “dry” period of English anthem composition, but the second half of the century saw a great blossoming of the genre, which continued into the 20th century and to the present. In this modern period the language of the text could be a vernacular or Latin. The list of distinguished motet- or anthem-writing composers is long. Just a few of them are Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-1876); Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900); Hubert Parry (1848-1918); Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924).

In America, the legacy of English anthem-writing was well represented beginning in the late 19th century. Two major figures must be mentioned here. Horatio Parker (1863-1919), recognized today primarily for his oratorio Hora Novissima (1893), wrote many anthems and hymns, as well as settings of the liturgy for Holy Communion and Morning and Evening services. He taught at cathedral schools and then the General Theological Seminary and National Conservatory of Music in New York City before embarking, in 1893, on a long and stellar career as professor and dean of the Yale School of Music. Leo Sowerby (1895-1968), organist and choirmaster at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. James in Chicago from 1927-1962, composed almost 100 anthems and other sacred music.

There are numerous examples today of grand anthems for large choirs as well as modest anthems for small forces; they might be accompanied or not. Regardless of the ecclesiastical setting in which they appear, anthems still carry on the long tradition of sacred compositional practice for texts other than the Mass.

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Judith Eckelmeyer ©2015

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.