- Home

- N - The Magic Flute

- NE - Welcome!

-

E - Other Music

- E - Music Genres >

- E - Composers >

-

E - Extended Discussions

>

- Allegri: Miserere

- Bach: Cantata 4

- Bach: Cantata 8

- Bach: Chaconne in D minor

- Bach: Concerto for Violin and Oboe

- Bach: Motet 6

- Bach: Passion According to St. John

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue in B-minor

- Bartok: String Quartets

- Brahms: A German Requiem

- David: The Desert

- Durufle: Requiem

- Faure: Cantique de Jean Racine

- Faure: Requiem

- Handel: Christmas Portion of Messiah

- Haydn: Farewell Symphony

- Liszt: Évocation à la Chapelle Sistine"

- Poulenc: Gloria

- Poulenc: Quatre Motets

- Villa-Lobos: Bachianas Brazilieras

- Weill

-

E - Grace Woods

>

- Grace Woods: 4-29-24

- Grace Woods: 2-19-24

- Grace Woods: 1-29-24

- Grace Woods: 1-8-24

- Grace Woods: 12-3-23

- Grace Woods: 11-20-23

- Grace Woods: 10-30-23

- Grace Woods: 10-9-23

- Grace Woods: 9-11-23

- Grace Woods: 8-28-23

- Grace Woods: 7-31-23

- Grace Woods: 6-5-23

- Grace Woods: 5-8-23

- Grace Woods: 4-17-23

- Grace Woods: 3-27-23

- Grace Woods: 1-16-23

- Grace Woods: 12-12-22

- Grace Woods: 11-21-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-31-2022

- Grace Woods: 10-2022

- Grace Woods: 8-29-22

- Grace Woods: 8-8-22

- Grace Woods: 9-6 & 9-9-21

- Grace Woods: 5-2022

- Grace Woods: 12-21

- Grace Woods: 6-2021

- Grace Woods: 5-2021

- E - Trinity Cathedral >

- SE - Original Compositions

- S - Roses

-

SW - Chamber Music

- 12/93 The Shostakovich Trio

- 10/93 London Baroque

- 3/93 Australian Chamber Orchestra

- 2/93 Arcadian Academy

- 1/93 Ilya Itin

- 10/92 The Cleveland Octet

- 4/92 Shura Cherkassky

- 3/92 The Castle Trio

- 2/92 Paris Winds

- 11/91 Trio Fontenay

- 2/91 Baird & DeSilva

- 4/90 The American Chamber Players

- 2/90 I Solisti Italiana

- 1/90 The Berlin Octet

- 3/89 Schotten-Collier Duo

- 1/89 The Colorado Quartet

- 10/88 Talich String Quartet

- 9/88 Oberlin Baroque Ensemble

- 5/88 The Images Trio

- 4/88 Gustav Leonhardt

- 2/88 Benedetto Lupo

- 9/87 The Mozartean Players

- 11/86 Philomel

- 4/86 The Berlin Piano Trio

- 2/86 Ivan Moravec

- 4/85 Zuzana Ruzickova

-

W - Other Mozart

- Mozart: 1777-1785

- Mozart: 235th Commemoration

- Mozart: Ave Verum Corpus

- Mozart: Church Sonatas

- Mozart: Clarinet Concerto

- Mozart: Don Giovanni

- Mozart: Exsultate, jubilate

- Mozart: Magnificat from Vesperae de Dominica

- Mozart: Mass in C, K.317 "Coronation"

- Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music,

- Mozart: Requiem

- Mozart: Requiem and Freemasonry

- Mozart: Sampling of Solo and Chamber Works from Youth to Full Maturity

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat

- Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major

- Mozart: Two Works of Mozart: Mass in C and Sinfonia Concertante

- NW - Kaleidoscope

- Contact

TWO WORKS OF MOZART

Perspectives on Two Mozart Works of the Early 1780s:

Mass in C, K. 317, and Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364

By Judith Eckelmeyer

In mid-January, 1779, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) reunited with his father and sister in Salzburg after a separation of a year and three months. The reunion was flawed, however. First, Wolfgang’s mother, who had made the long journey with him, died the previous summer in Paris, and her absence was a bitter pill for the family to swallow. But also, Wolfgang was returning to take a job he detested in a musical environment that had in every way been superseded in other cities he had visited. Now, as of February 25, he was to be the Court Organist to Archbishop Hieronimous Colloredo and also compose new works for services at the cathedral. And herein lay a good part of the problem: Colloredo, in an effort toward “enlightened” practice, insisted that church music be straight-forward and without musical elaboration that would obscure the text, and that Masses be completed within 45 minutes. Very limited, then, were opportunities for Mozart to try his hand at exploring all the new instruments and expressive devices to which he had been exposed, in the Mannheim portion of his travels particularly, when writing for the church.

What were these novelties from the Mannheimers, whose symphonies were so startlingly different? First, they employed a new single-reed instrument—the clarinet—a Bohemian form of which they brought with them to the court of the Palatinate Elector. Its distinctive sound would become a critical ingredient in Mozart’s operas, serenades and symphonies in the 1780s. Second, the Mannheim orchestra’s legendary precision and unity of ensemble made effective a new kind of theme—a fast, unison, upward arpeggio known as the “Mannheim rocket” (like the opening of the last movement of the 40th symphony). Third, and especially important, the Mannheimers relished dynamic effects. Sudden changes from loud to soft were bold and arresting. String tremolos (fast repeated notes)that crescendo from piano to fortissimo created a hair-raising excitement and were called the “Mannheim steamroller” (the original use of the term!). These and other devices in the use of thematic material would find their way into Mozart’s compositions, notably after he moved to Vienna.

However, now in Salzburg and dealing with his appointment under Colloredo, Mozart threw himself into composing. Although he wrote some secular instrumental music over the next several months, he almost immediately created several major pieces for the church. Among these were two Masses, K. 317 and 337, two Vespers services, K. 321 and 339, and two church sonatas, K. 328 and 329, along with some shorter sacred works.

MOZART’S MASS IN C, K. 317, “CORONATION”

The Mass in C, K. 317 is nicknamed the “Coronation” Mass. Mozart completed it probably on March 23, 1779, for use on Easter Sunday, April 4. The nickname for this mass was a puzzle for over a century until in 1907 Johann Evangelist Engl proposed that Mozart had composed it for the ceremony of the crowning of the image of the Virgin Mary at the pilgrimage church at Maria Plain, just outside Salzburg. However, after further research published in 1963, this explanation has been discounted, and many solid reasons have been cited then and since to indicate that the mass received its nickname from the fact that it was performed under the direction of Antonio Salieri at the coronation of Leopold II as the new Holy Roman Emperor in 1790 and as King of Bohemia in 1791, and again, after Leopold’s unexpected early death, for the coronation of his his successor, Francis II, as Holy Roman Emperor in 1792. Dennis Pajot points out that the title “Mass in C for the Coronation Celebration of His Majesty Francis I as Emperor of Austria” was applied to a copy of the performance parts at the Austrian National Library in 1820, and apparently the name became attached to it thereafter.

Mozart planned a festive work in the “Coronation” Mass. It requires two each of oboes, horns, and trumpets, two violin parts, string basses, timpani, and organ; soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists; and a four-part choir. (Three trombones also in the score are used to support the lower three choral voices.) In setting the five “ordinary” sections of the Mass, however, Mozart achieved not only Archbishop Colloredo’s required brevity but also a unity and relatedness between the sections. For instance, the opening of the Kyrie, Gloria, and Credo are alike in their strongly uneven rhythms, in spite of tempo and metrical differences. In an even stronger link between movements, the soloists’ material of the Kyrie movement reappears in the fifth section, at the words “Dona nobis pacem”. And throughout the Mass, melodic gestures of similar construction resonate as from one general concept.

A few words about each of the sections may serve to bring a listener’s attention to Mozart’s special treatment of the text.

Kyrie eleison: Although the full text of the section is present, Mozart concentrates on the “Kyrie”, relegating the “Christe” to a few brief phrases in the middle of the movement. The slow, dotted opening (Andante maestoso) by the choir suggests a French Overture and royal ceremony. The arresting opening forte and sudden drop to piano on the word “Kyrie” occurs against a crescendo marked for the orchestra—a miniature moment of drama thanks to the Mannheimers’ dynamic devices. Soloists continue the “Kyrie” with a new theme (which will reappear in the last movement), and in the midst of this more extended section the brief “Christe” occurs. The chorus completes the movement with the return of the slow theme that opened the movement.

Gloria: The long text is shared between choral and soloists’ statements at a vigorous pace. Primarily in C major, the movement has occasional minor-key moments at key phrases: “qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis”, and “suscipe deprecationem nostram”. One hopes the Archbishop forgave the few passages of contrapuntal working, as the text is still clear in the well-separated soprano line. A few instances of word-painting can be detected, for example at “tu solus altissimus”.

Credo: A march-like attitude pervades the movement, beginning with a decisive and forceful rhythm on one note in the unison voices against an energy-filled orchestra accompaniment. (This theme returns several times, forming a rondo structure.) Mozart explores the dramatic potential of the text by using the Mannheim dynamics and surprising off-beat rhythms which drive the music forward, and there is plenty of word-painting. At the words “Et incarnatus est” the movement’s energy changes radically, as a new tempo, greater harmonic intensity, and more delicate accompanying figure change the atmosphere. Soloists present this most intimate text quite tenderly, and the subsequent chorus outburst at “Crucifixus” begins a section of increasing tension that is released only at “sepultus est.” Mozart uses those Mannheim dynamics to great effect here. Note the word-painting as Christ is entombed. (One might put this passionate section into the context of Mozart’s very recent experience of losing the woman from whom he was born, and who was buried in Paris, far away from her family.) The fast tempo returns at “Et resurrexit”. The extended “Amen” at the end of the movement seems to be a sly trick on the Archbishop, for it isn’t really the end: Mozart begins the Credo text again briefly before coming around again to two really terse “Amens”.

Sanctus: This is another Andante maestoso movement, in triple meter, with the regal dotted rhythms of the French Overture, leading to the quite fast and dance-like “Osanna”.

Benedictus: The tempo is a moderate Allegretto duple meter, and the heavier instruments of the orchestra are silent here, leaving only a delicate staccato Alberti-bass accompaniment in the violins and a simple bass line to introduce the solo quartet, where the oboes and horns also enter. The chorus returns at its fast triple meter to repeat the “Osanna”. But again—perhaps to surprise the Archbishop—this “Osanna” is not the end! Once again the solo quartet brings a reprise of their “Benedictus”, and only after this does the chorus provide a closing “Osanna”.

Agnus Dei: Mozart rebalances the normal three part structure of the Agnus Dei section so that the first two statements “Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis” and the beginning “Agnus Dei” of the third statement fall to the soprano soloist, and the choir sings the remaining “dona nobis pacem”. The soprano soloist’s Agnus Dei is one of the major marvels of Mozart’s pre-Vienna career. Her melody, beginning so like the Countess’s “Dove sono” of some seven years later, is infinitely expressive in the current “Sensitive” style, yet beautifully rococo with tasteful ornaments and flowing lines. The orchestra’s violins are muted over the pizzicato bass. Subtle but expressive dynamics of Mannheim origin support exquisite harmonic changes. The remarkable bubble bursts with the shift into the faster and more cheerful segment, “Dona nobis pacem”, introduced by the soloists and extended with interplay between choir and solo ensembles. Far from a perfunctory statement, the Dona nobis pacem movement is full of lively rhythms and surprises at almost every turn—Mozart stretching the boundaries.

The C-major Mass, K. 317, may be considered the “public” face of Mozart. Here all is positive, confident, and, excepting for a few moments of minor-key darkness and dynamic drama, charming and sunny. Deep introspection is fleetingly present at the “et incarnatus est” through the “passus et sepultus est” in the Credo, but Mozart did not extend this material as he did other text passages such as the “Agnus dei” and the “Dona nobis pacem”.

SINFONIA CONCERTANTE, E-Flat Major, K. 364

Some months after composing the C-major Mass, Mozart created an entirely different work—this one strictly instrumental, secular, and with no known performance in mind. This is the Sinfonia concertante in E-flat, K. 364, for solo violin and viola with an orchestra of two oboes, two horns and strings. This is a kind of classical-era concerto-grosso, using more than one soloist. It is set up like other concertos Mozart wrote, with three movements in a fast-slow-fast arrangement. But this is a work with a difference: in it, we find one of the most intimately expressive movements—the second—of Mozart’s entire compositional oeuvre, couched between two intriguing but sunny and delightful movements. The emotional differences between the second and the surrounding movements are so astonishing as to need commentary and even speculation.

Remember that in January of 1779 Mozart had returned from a trip in which he had lost his mother. He had delayed telling his father and sister about her death, trying to spare them the shock by writing at first only of her serious illness. We can only imagine what his father and sister felt when the full story reached them, and when Wolfgang returned to Salzburg alone. His mother, Anna Maria, was in so many ways the heart of the family, sharing a ribald sense of humor with Wolfgang and, if we can read between the lines, the softening agent to his father Leopold’s strictness. What kind of tribute would suffice for her? What would both express and assuage the grief the three of them felt at her loss?

I think the Sinfonia concertante is her memorial at Wolfgang’s hand. The solo instrumentation is telling. Leopold was a known and respected teacher of the violin and author of a manual on playing the violin. Wolfgang played both violin and viola. The higher-voiced violin seems a reference to a child, while the lower viola seems more adult, especially in the range for which Mozart wrote in this work. So much of the Sinfonia concertante solo writing is a dialogue between violin and viola that we can imagine a conversation going on between Leopold and Wolfgang, although in reversed voice ranges. Or perhaps we might think of the violin as a female voice—Anna Maria’s?—and the viola a young male voice—Wolfgang’s?—in a suggestion of conversation over her illness and the possibility of her death. Although we can never know Mozart’s intention for the way he handled the two soloists, it’s clear that the dialogue is there. The most intense, sensitive, and poignant middle movement dialogue, presented in the minor key, has no equal in any of Mozart’s other works.

This highly private and extraordinarily moving work is the interior “face” of Mozart, where he reveals something other than the cheerful persona of the public personage he presented in the Mass in C, regardless of the several more intimate and tender moments in that work.

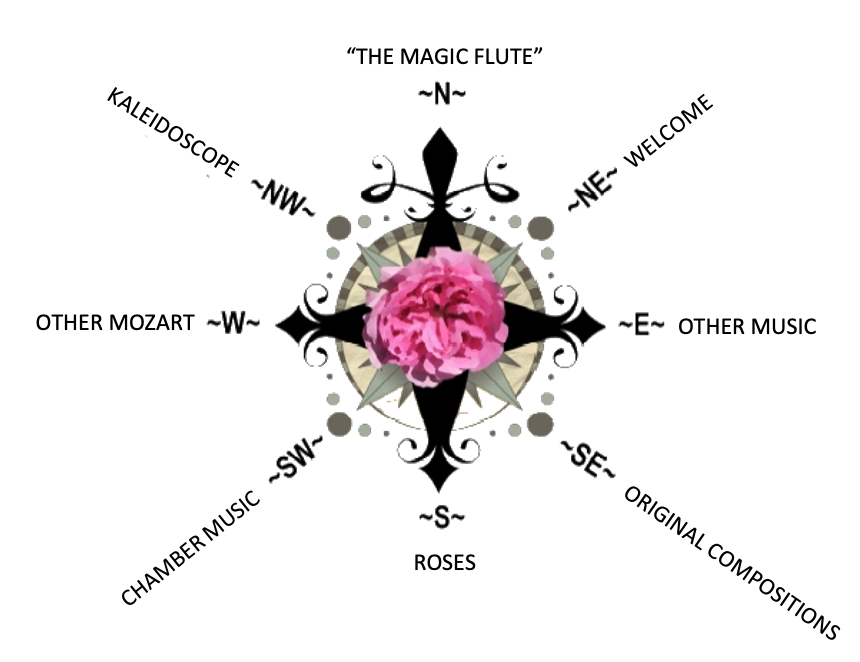

Choose Your Direction

The Magic Flute, II,28.